Difference between revisions of "Thomas Jefferson"

m (→Wythe books willed to Jefferson) |

|||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

Jefferson was born in 1743 in Shadwell, Virginia to Peter Jefferson, a surveyor, and his wife Jane Randolph Jefferson, a member of the very wealthy and prominent Randolph family.<ref>Merrill D. Peterson, "Jefferson, Thomas" in ''American National Biography Online'', accessed 21 October 2013, http://www.anb.org/articles/02/02-00196.html.</ref> The elder Jefferson died when Thomas was only 14, leaving to his son an estate of 5,000 acres and many slaves.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Three years later, Jefferson enrolled at William & Mary College — studying mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under the tutelage of Dr. William Small.<ref>Merrill D. Peterson, ''Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).</ref> | Jefferson was born in 1743 in Shadwell, Virginia to Peter Jefferson, a surveyor, and his wife Jane Randolph Jefferson, a member of the very wealthy and prominent Randolph family.<ref>Merrill D. Peterson, "Jefferson, Thomas" in ''American National Biography Online'', accessed 21 October 2013, http://www.anb.org/articles/02/02-00196.html.</ref> The elder Jefferson died when Thomas was only 14, leaving to his son an estate of 5,000 acres and many slaves.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Three years later, Jefferson enrolled at William & Mary College — studying mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under the tutelage of Dr. William Small.<ref>Merrill D. Peterson, ''Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).</ref> | ||

| − | Small recognized great promise in Jefferson and recommended him to [[George Wythe]], one of the most prominent lawyers in Virginia, as an apprentice.<ref>Fawn McKay Brodie, ''Thomas Jefferson, an Intimate History'', 1st ed. (New York: Norton, 1974), 45.</ref> At that time in the colonies, there were no law schools; most budding lawyers learned by apprenticing themselves to a practicing attorney. Jefferson spent the | + | Small recognized great promise in Jefferson and recommended him to [[George Wythe]], one of the most prominent lawyers in Virginia, as an apprentice.<ref>Fawn McKay Brodie, ''Thomas Jefferson, an Intimate History'', 1st ed. (New York: Norton, 1974), 45.</ref> At that time in the colonies, there were no law schools; most budding lawyers learned by apprenticing themselves to a practicing attorney. Jefferson spent the three years learning the intricacies of the law under Wythe and was admitted to the bar in 1767.<ref>Peterson, "Jefferson, Thomas."</ref> Wythe’s tutelage had a profound impact on the young lawyer. In his autobiography, Jefferson recognized Wythe as one of the three most influential men in his life, along with Dr. Small and Jefferson’s benefactor, Peyton Randolph.<ref>Brodie, ''Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History,'' 110</ref> Jefferson described Wythe as "my faithful and beloved mentor in youth and my most affectionate friend through life"<ref>Thomas Jefferson, ''Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson'' (Raleigh, N.C.: Alex Catalogue), 5.</ref> and "my ancient master, my earliest and best friend."<ref>"[[Jefferson-DuVal Correspondence#Thomas Jefferson to William_DuVal, 14 June 1806|Thomas Jefferson to William DuVal, June 14, 1806]]," ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers,'' Library of Congress, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib016197.</ref> |

In 1769, Jefferson added a political career to his practice of law, being elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses.<ref>Peterson, "Jefferson, Thomas."</ref> He gained notoriety for his support of the revolutionary cause, and in 1775 Jefferson was elected to the Second Continental Congress where he began drafting revolutionary state papers.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In June, 1776, Jefferson was tasked to draft a declaration of independence from Britain that would fairly represent all 13 colonies. | In 1769, Jefferson added a political career to his practice of law, being elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses.<ref>Peterson, "Jefferson, Thomas."</ref> He gained notoriety for his support of the revolutionary cause, and in 1775 Jefferson was elected to the Second Continental Congress where he began drafting revolutionary state papers.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In June, 1776, Jefferson was tasked to draft a declaration of independence from Britain that would fairly represent all 13 colonies. | ||

Revision as of 14:09, 19 February 2018

| Thomas Jefferson | |

| Third President of the United States | |

| In office | |

| March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1809 | |

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

| Second Governor of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| June 1, 1779 – June 3, 1781 | |

| Preceded by | Patrick Henry |

| Succeeded by | William Fleming |

| Delegate to the Second Continental Congress from Virginia | |

| In office | |

| June 20, 1775 – September 26, 1776 | |

| Preceded by | George Washington |

| Succeeded by | John Harvie |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 13, 1743 |

| Shadwell, Virginia | |

| Died | July 4, 1826 (aged 83) |

| Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S. | |

| Education | Legal apprentice to George Wythe |

| Alma mater | College of William & Mary |

| Profession | Statesman Planter Lawyer Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Martha Wayles |

| Known for | Author of the United States Declaration of Independence Father of the University of Virginia |

In addition to drafting and signing the Declaration of Independence and serving two terms as the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson (1743 – 1826) was also a successful diplomat, lawyer, philosopher, and amateur architect.

Jefferson was born in 1743 in Shadwell, Virginia to Peter Jefferson, a surveyor, and his wife Jane Randolph Jefferson, a member of the very wealthy and prominent Randolph family.[1] The elder Jefferson died when Thomas was only 14, leaving to his son an estate of 5,000 acres and many slaves.[2] Three years later, Jefferson enrolled at William & Mary College — studying mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under the tutelage of Dr. William Small.[3]

Small recognized great promise in Jefferson and recommended him to George Wythe, one of the most prominent lawyers in Virginia, as an apprentice.[4] At that time in the colonies, there were no law schools; most budding lawyers learned by apprenticing themselves to a practicing attorney. Jefferson spent the three years learning the intricacies of the law under Wythe and was admitted to the bar in 1767.[5] Wythe’s tutelage had a profound impact on the young lawyer. In his autobiography, Jefferson recognized Wythe as one of the three most influential men in his life, along with Dr. Small and Jefferson’s benefactor, Peyton Randolph.[6] Jefferson described Wythe as "my faithful and beloved mentor in youth and my most affectionate friend through life"[7] and "my ancient master, my earliest and best friend."[8]

In 1769, Jefferson added a political career to his practice of law, being elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses.[9] He gained notoriety for his support of the revolutionary cause, and in 1775 Jefferson was elected to the Second Continental Congress where he began drafting revolutionary state papers.[10] In June, 1776, Jefferson was tasked to draft a declaration of independence from Britain that would fairly represent all 13 colonies.

Jefferson's political career continued after his service in the Continental Congress. He served as Governor of Virginia (1779-1781), Minister to France (1785-89), Secretary of State (1790-1793), Vice President (1797-1801), and ultimately as President of United States (1801-1809).

Finished with politics after his second term as president, Jefferson retired to Monticello, the home he had built near Charlottesville, Virginia. As an avid student of architecture, he modeled the house after the work of Italian Renaissance master Andrea Palladio;[11] he repeated a similar design in his later works—the Virginia Capitol, Poplar Forest, and the University of Virginia.[12]

Jefferson wrote his own epitaph. In it, he identified the accomplishments of which he was most proud: the Declaration of Independence, the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and the founding of the University of Virginia.[13] Jefferson died at Monticello on July 4th, 1826 — the 50th anniversary of the announcement of American independence. Coincidentally, John Adams, a partner in the Continental Congress, a bitter political rival, and ultimately a rediscovered friend, died on the same day. Adam's reported last words, knowing nothing of Jefferson's death earlier on that same morning, were "Thomas Jefferson still survives."[14]

Wythe books willed to Jefferson

When George Wythe died in 1806, he willed his library and scientific equipment to Jefferson. Of the 332 titles listed on an inventory made by Jefferson, he kept 149 titles for his own library, and gave away 183 to various family members, a joiner who worked at Monticello, and his grandson's tutor. The list of books Jefferson retained follows, and is subdivided into categories assigned by Jefferson.[15] Click on the titles to learn more about the works.

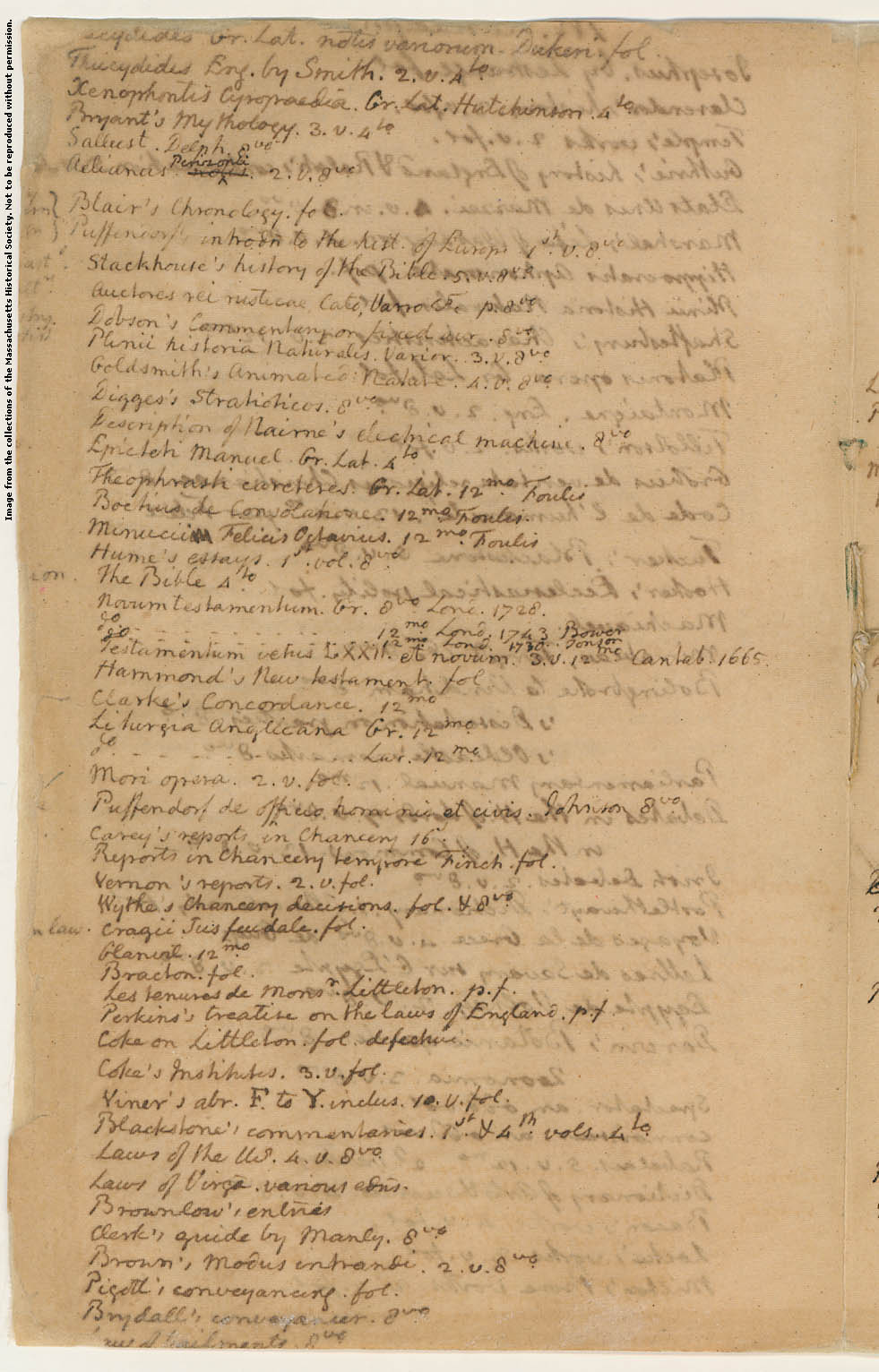

Page six of Jefferson's inventory of books received from George Wythe's estate, September, 1806. This list indicates which volumes Jefferson intended to keep for himself. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

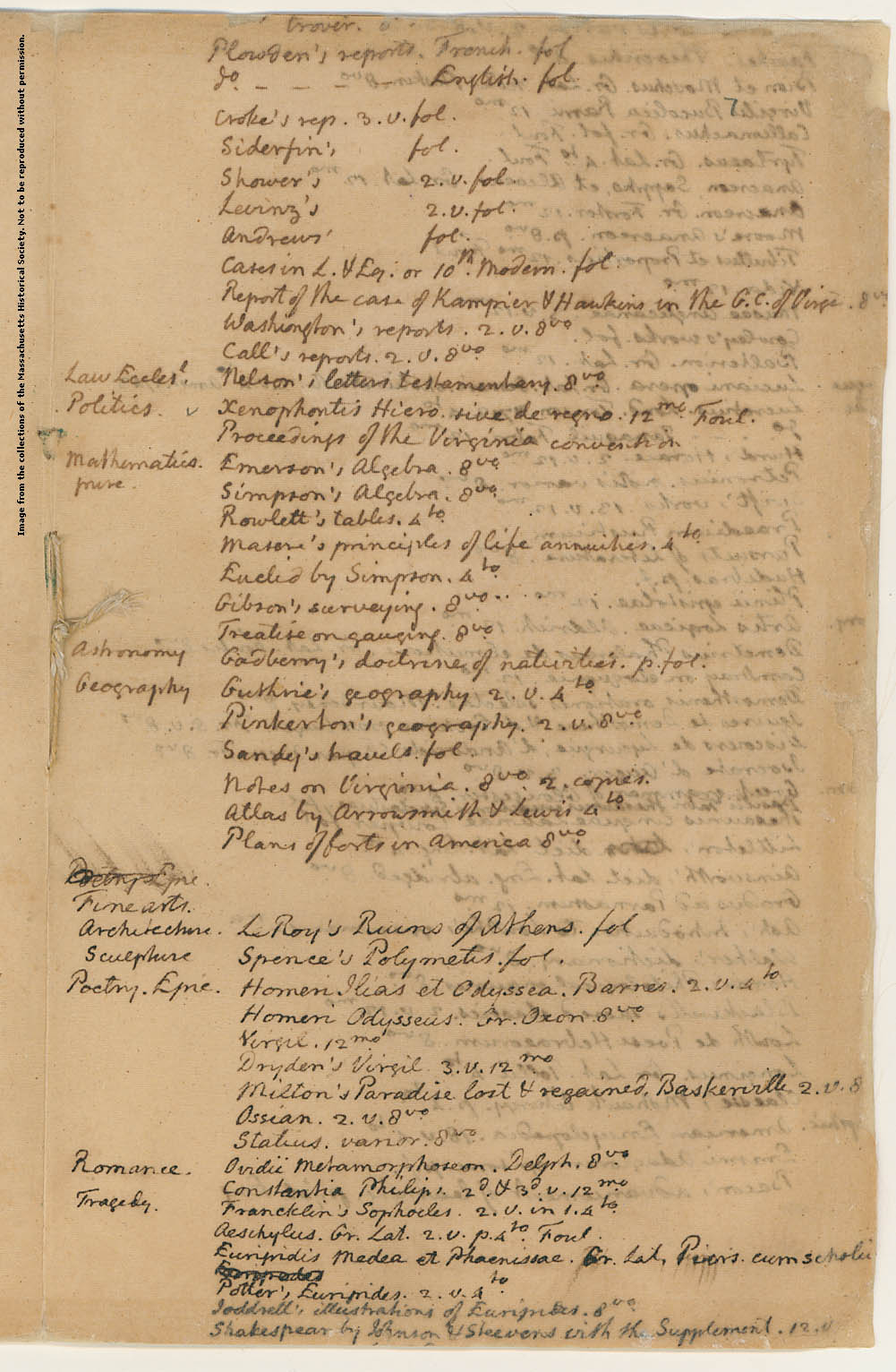

Page seven of Jefferson's inventory. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

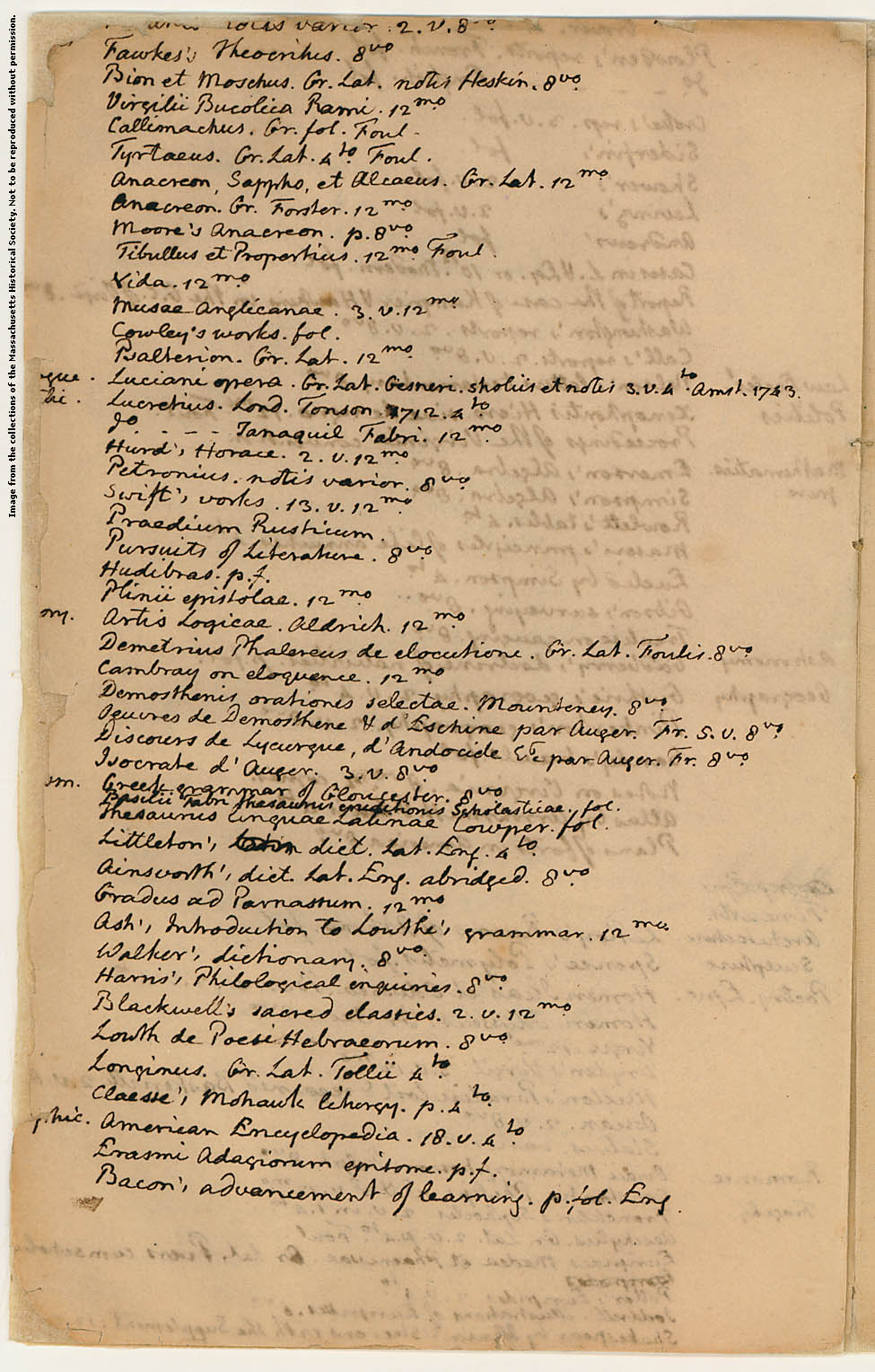

Page eight of Jefferson's inventory. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

See also

- Jefferson Inventory

- Memoir, Correspondence and Miscellanies from the Papers of Thomas Jefferson

- Wythe the Teacher

References

- ↑ Merrill D. Peterson, "Jefferson, Thomas" in American National Biography Online, accessed 21 October 2013, http://www.anb.org/articles/02/02-00196.html.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).

- ↑ Fawn McKay Brodie, Thomas Jefferson, an Intimate History, 1st ed. (New York: Norton, 1974), 45.

- ↑ Peterson, "Jefferson, Thomas."

- ↑ Brodie, Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History, 110

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson (Raleigh, N.C.: Alex Catalogue), 5.

- ↑ "Thomas Jefferson to William DuVal, June 14, 1806," The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib016197.

- ↑ Peterson, "Jefferson, Thomas."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ This list was adapted from the "Library of George Wythe" in the Thomas Jefferson Libraries project on the website for Monticello. See: "Library of George Wythe," Thomas Jefferson Libraries, Monticello, accessed July 2, 2013. For the manuscript version, see "Inventory of the Books Received by Thomas Jefferson from the Estate of George Wythe, Circa September, 1806," Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed July 2, 2013.

- ↑ The entry for "Wythe's Chancery decisions" includes the folio volume of Wythe's Decisions of Cases in Virginia, by the High Court of Chancery (1795), and six octavo pamphlets reporting seven cases published in 1796 and later: Case upon the Statute for Distribution, Report of the Case between Field and Harrison, Between Fowler and Saunders, Between Wilkins and Taylor, Between Yates and Salle, and Love against Donelson.

- ↑ The parties reported are Peter Kamper (not Kampier) and Mary Hawkins. See Report of Kamper v. Hawkins.