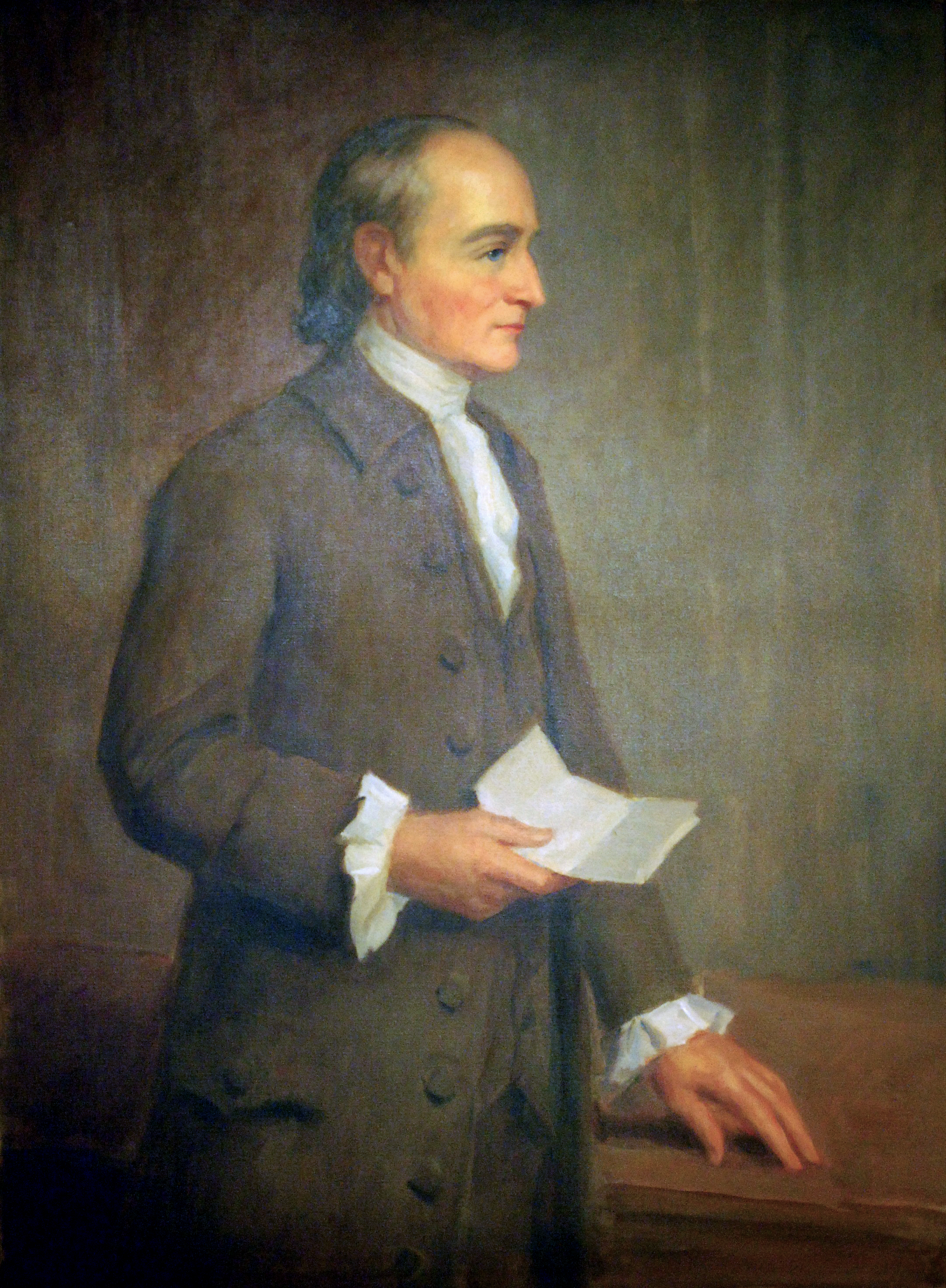

George Wythe

| Chancellor | |

| George Wythe | |

| Chancellor of the Commonwealth of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| December 24, 1788 – January 23, 1802 | |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Judge, High Court of Chancery of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| January 14, 1778 – June 8, 1806 | |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Creed Taylor |

| Professor of Law and Police, College of William & Mary | |

| In office | |

| December 4, 1779 – September 15, 1789 | |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | St. George Tucker |

| Delegate to the Constitutional Convention | |

| In office | |

| May 25, 1787 – June 16, 1787 | |

| Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates | |

| In office | |

| May 8, 1777 – May 11, 1778 | |

| Preceded by | Edmund Pendleton |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Harrison V |

| Delegate to the Second Continental Congress | |

| In office | |

| August 11, 1775 – January 29, 1777[1] | |

| Succeeded by | Mann Page |

| Member of the Virginia House of Burgesses | |

| In office | |

| 1754 – 1775 | |

| Preceded by | Armistead Burwell |

| Mayor of the City of Williamsburg, Virginia | |

| In office | |

| November 30, 1768 – November 29, 1769 | |

| Preceded by | James Cocke |

| Succeeded by | John Blair |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1726 |

| Elizabeth City Co., Virginia | |

| Died | June 8, 1806 (aged 80) |

| Richmond, Virginia, U.S. | |

| Resting place | St. John's Church Richmond, Virginia |

| Residence(s) | Chesterville Plantation, Elizabeth City Co., Virginia Prince George Co., Virginia Spotsylvania Co., Virginia Williamsburg, Virginia Richmond, Virginia |

| Profession | Lawyer Professor of Law and Police (1779–1789) Chancery Court Judge (1778–1806) |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Lewis (1747–1748) Elizabeth Taliaferro (1755–1787) |

| Relatives | Thomas Wythe (father) Margaret Walker Wythe (mother) Thomas Wythe (elder brother) Anne Wythe Sweeney (elder sister) |

| Known for | Signer of the United States Declaration of Independence |

| Signature | |

George Wythe (/dʒɔː(ɹ)dʒ/ /wɪð/)[2] (1726 – June 8, 1806) signer of the Declaration of Independence, first law professor in America, and chancery court judge, was born in Elizabeth City County, Virginia. Wythe spent the majority of his life in the Commonwealth, only traveling outside it to attend the Second Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

Wythe's impact on American law cannot be overstated. In the course of his careers as lawyer, legislator, judge, and professor Wythe taught a "who's who" of statesmen and jurists:

Among those who shared the magic of Wythe's teaching were Thomas Jefferson, third president, secretary of state, minister to France and governor of Virginia; John Marshall, chief justice of the United States; Henry Clay, secretary of state, speaker of the House of Representatives and United States senator from Kentucky; Littleton W. Tazewell, United States senator and governor of Virginia; John Brown, one of the first two United States senators from Kentucky; and St. George Tucker, John Coalter and Spencer Roane, justices of the Virginia Supreme Court.[3]

Wythe died at his home in Richmond on June 8, 1806.

Contents

Early life

- Main article: Wythe's Early Life

George Wythe, the second son of Thomas Wythe, III,[4] and Margaret Walker Wythe, was born in 1726, most likely in the first half of the year.[5] Wythe's father owned the family plantation, Chesterville, in Elizabeth City County (now Hampton), Virginia, where he was also a local justice and sheriff and served as a member in the Virginia House of Burgesses. When the senior Wythe died intestate in 1729, all his property passed to his oldest son, Thomas IV, leaving young George dependent upon his own resources.[6] He grew up at Chesterville and may have attended the Grammar School at the College of William & Mary[7] before leaving to study law near Petersburg, Virginia, with his uncle Stephen Dewey.[8] The young apprentice spent three or four years in training. Instead of fond remembrances, Wythe viewed his legal education with dissatisfaction, stating that Dewey "treated him with neglect, and confined him to the drudgeries of his office, with little, or no, attention to his instruction in the general science of law."[9]

Legal and political careers

- Main article: Wythe the Lawyer

- Main article: Wythe the Politician

In the spring of 1746, Wythe successfully appeared before examiners to procure his license to practice law in the county courts. The license was signed by Peyton Randolph, Lawrence Burford, William Nimmo, and Stephen Dewey.[10] Wythe's first job was as a partner to Zachary Lewis of Spotsylvania County, and he married Lewis's daughter Ann on December 26, 1747.[11] Sadly, Ann died within the first year of married life on August 8, 1748. In response to this tragedy, Wythe returned to the Tidewater region and began the first of many political appointments as clerk to two powerful committees in the House of Burgesses, the Committee on Privileges and Elections and the Committee on Propositions and Grievances.[12]

In 1754, Wythe briefly replaced Peyton Randolph as Attorney General for the colony and qualified to practice before the General Court (the highest court).[13] The next year Wythe's older brother Thomas died, leaving him the Chesterville plantation. Around the same time, Wythe married Elizabeth Taliaferro, whose father Richard built the couple the house on the Palace Green in Williamsburg, now known as the George Wythe House. Wythe proceeded to serve eighteen years as one of Williamsburg's aldermen, was elected to the House of Burgesses, and became clerk of the House from 1768 to 1775. He continued to practice law, and his clients included George Washington, Richard Henry Lee, and Robert Carter. In 1776, the Virginia House of Delegates elected Wythe a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. There he signed the Declaration of Independence. Wythe later represented Virginia briefly at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia but was forced to leave due to the terminal illness of his wife Elizabeth. When Virginia debated ratification of the Constitution, Wythe served as Chairman of the Committee of the Whole and introduced the resolution calling for ratification.[14]

Wythe the teacher

- Main article: Wythe the Teacher

Wythe originally began his teaching career in the traditional eighteenth century manner of instructing apprentices in his legal practice. Historians believe Wythe started instructing apprentices in his Williamsburg home before 1762 when Thomas Jefferson began to read law, but no records verify or identify earlier students.[15] Subsequent Wythe apprentices included James Madison (future Episcopal bishop of Virginia and president of William & Mary College) and St. George Tucker (Wythe’s successor as professor of law and police).[16]

In 1779, William & Mary’s Board of Visitors reorganized the college and created the chair of Professor of Law and Police — the first of its kind in America and only the second in the English-speaking world.[17] The Board appointed George Wythe to fill the new chair, making him both William & Mary’s first law professor and the first law professor in the country.

Wythe lectured twice a week and assigned readings from major legal treatises such as William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England and Matthew Bacon’s New Abridgment of the Law. He also introduced the use of mock trials and mock legislatures to American legal education in an effort to prepare his students for roles as "citizen lawyers." Wythe’s students included future United States Supreme Court justices John Marshall and Bushrod Washington, three future Virginia Supreme Court Justices, and numerous future Congressmen and Senators. In 1789, the Virginia High Court of Chancery, on which Wythe had served since its inception in 1778, relocated to Richmond. This change and Wythe’s growing unhappiness with the direction of academic life at the College caused Wythe to resign his position as professor.[18]

Judicial career

- Main article: Wythe's Judicial Career

On January 9, 1778, Virginia's General Assembly passed an Act creating the High Court of Chancery. Five days later, the Assembly nominated and unanimously elected Edmund Pendleton, Robert Carter Nicholas and Wythe to the bench.[19] In addition to their chancery court obligations, an Act of the Assembly in 1779 required all three judges to serve ex officio on the Court of Appeals with judges from the Court of Admiralty and the General Court.[20] This changed in December, 1788 when the Assembly reorganized the courts and created a permanent Court of Appeals, leaving Wythe as the sole chancellor, and his decisions subject to review by the Court of Appeals.[21] Wythe retained his position as chancellor until his death in 1806.

Wythe and slavery

- Main article: George Wythe and Slavery

At both his Chesterville plantation and his Williamsburg home, George Wythe owned slaves. Despite this, Wythe supported manumission or abolition at various points in his legal and judicial careers.

Death

- Main article: Death of George Wythe

On May 25, 1806, George Wythe was struck with a severe gastrointestinal malady which most of his contemporaries (and subsequent historians) believed resulted from arsenic poisoning.[22] The culprit believed to have administered the poison to Wythe's entire household was his great-nephew and heir, George Wythe Sweeney. Also poisoned were Lydia Broadnax, Wythe's housekeeper, and Michael Brown, a young freedman to whom Wythe was teaching Latin and Greek. Broadnax survived the poisoning; Brown did not, and died on June 1. Wythe survived in agony for two weeks, long enough to disinherit Sweeney. The chancellor finally succumbed on June 8.[23] The great teacher and judge was mourned throughout the Commonwealth with "more column inches of eulogy than had been elicited in Virginia newspapers by the death of George Washington or by that of any other person."[24] Even at his death, his influence upon the nation was readily apparent. As one commentator wrote, "upon his death in 1806, the nation's President (Jefferson), its Chief Justice (Marshall), an Associate Justice (Washington), the Attorney General (Breckinridge), U.S. Senators from Virginia (Giles) and Kentucky (Thruston), and the most influential state judge in America (Roane) all were former students of George Wythe."[25]

References

- ↑ Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia, December 4, 1776 (Richmond, VA: Samuel Shepherd, 1828), 81.

- ↑ George Wythe pronounced his surname like "with". Joyce Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, (New York: Harper & Row, 1975) xii.

- ↑ Thomas Alonzo Dill, George Wythe: Teacher of Liberty (Williamsburg, VA: Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission, 1979), 1-2.

- ↑ Ibid., 3.

- ↑ The exact date of Wythe's birth is unknown, but W. Edwin Hemphill cites the American Law Journal, 3 (1810), 97, that Wythe died in the "eighty-first year of his age" in June 1806. "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia," PhD diss., University of Virginia, 1937, 31. For a more lengthy discussion of Wythe's birth year, see Appendix C in Robert Bevier Kirtland, George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge, (New York: Garland Publishing, 1986), 305-307.

- ↑ William Clarkin,Serene Patriot: A Life of George Wythe (Albany, New York: Alan Publications, 1970), 4.

- ↑ Ibid., 5.

- ↑ Dill, George Wythe: Teacher of Liberty, 8-9.

- ↑ Daniel Call, "George Wythe," in Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia 2nd ed. (Richmond, VA: Robert I. Smith, 1833), 4:xi.

- ↑ Dill, George Wythe: Teacher of Liberty, 10.

- ↑ Ibid., 10,12.

- ↑ Ibid., 12.

- ↑ Ibid., 17.

- ↑ Ibid., 68-70.

- ↑ Thomas Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," in The History of Legal Education in the United States: Commentaries and Primary Sources, ed. Steve Sheppard (Pasadena, CA: Salem Press, 1999), 1:142.

- ↑ Ibid., 1:143.

- ↑ William Clarkin, Serene Patriot: A Life of George Wythe (Albany, New York: Alan Publications, 1970), 141-142.

- ↑ Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," 157-158.

- ↑ Robert B. Kirtland, George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge, 119; Thomas Alonzo Dill, George Wythe: Teacher of Liberty (Williamsburg, Va.: Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission, 1979), 40.

- ↑ Dill, George Wythe: Teacher of Liberty, 40.

- ↑ William Brockenbrough, Virginia Cases: Or, Decisions of the General Court of Virginia, Vol. 2 (Richmond, VA: Peter Cottom, 1826), xiii.

- ↑ Daniel P. Berexa, "The Murder of Founding Father George Wythe." Tennessee Bar Journal 47 (Jan. 2011): 24.

- ↑ Ibid., 25.

- ↑ W. Edwin Hemphill, "Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder: A Documentary Essay," The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., 12, no. 4 (Oct., 1955): 545.

- ↑ Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," 161.

Further reading

- Main article: George Wythe Bibliography

- Blackburn, Joyce. George Wythe of Williamsburg. New York: Harper & Row, 1975.

- Brown, Imogene E. American Aristides: A Biography of George Wythe. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, c1981.

- Clarkin, William. Serene Patriot: A Life of George Wythe. Albany, New York: Alan Publications, 1970.

- Dill, Alonzo Thomas. George Wythe: Teacher of Liberty. Williamsburg, Va.: Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission, 1979.

- Hemphill, William Edwin. "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia." PhD diss., University of Virginia, 1937.

- Hemphill, William Edwin. "George Wythe, America's First Law Professor and the Teacher of Jefferson, Marshall and Clay." Masters thesis, Emory University, 1933.

- Holt, Wythe. "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," Alabama Law Review 58 (2007), 1009-1039.

- Hunter, Thomas. "The Teaching of George Wythe." In The History of Legal Education in the United States: Commentaries and Primary Sources, edited by Steve Sheppard, 1:138-168. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press, 1999.

- Kirtland, Robert Bevier. George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge. New York: Garland, 1986.

- Munson, Suzanne. Jefferson's Godfather: The Man Behind the Man. Richmond, Virginia: The Oaklea Press, 2018.

- Shewmake, Oscar L. The Honourable George Wythe: Teacher, Lawyer, Jurist, Statesman: An Address Delivered Before the Wythe Law Club of the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, Dec. 18, 1921. Richmond, Va., 1950.

External links

- George Wythe, August 30, 1779-March 5, 1789, Virginia Appellate Court History.