Difference between revisions of "Wythe the Lawyer"

m (→General Court cases) |

m (→General Court cases) |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

*''[[Howell v. Netherland]]'' | *''[[Howell v. Netherland]]'' | ||

*''[[Hudson v. Hudson]]'' | *''[[Hudson v. Hudson]]'' | ||

| − | *''[[Hunter v. | + | *''[[Hunter v. Glassell]]'' |

*''[[Id. v. Jno Black]]'' | *''[[Id. v. Jno Black]]'' | ||

*''[[Jefferson v. Stith]]'' | *''[[Jefferson v. Stith]]'' | ||

Revision as of 09:26, 22 August 2023

George Wythe may be best known for being a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a judge on the High Court of Chancery, and for training some of the most influential legal minds of the 18th century at William & Mary, but before any of that Wythe spent a large portion of his life as a successful lawyer. Like most of Wythe's life what we know about his legal career comes not from his own legal notes, but from contemporaneous letters and newspapers as well as what cases we can find in county court records and Thomas Jefferson's case notes.[1] From these sources, however, we can sketch the contours of a successful legal career that extended over 30 years.

At the time Wythe entered the profession, legal training varied and was not as regimented as it is today. Often men who wanted to be attorneys learned in a current attorney's practice, called an apprenticeship.[2] George Wythe's legal training was no different. While his first teacher was likely his mother, who taught him reading, writing, and arithmetic, Wythe had no formal legal training like law school.[3] There is some conjecture that he attended William & Mary for some formal education between 1730 and 1735.[4] But, he begins his formal legal training by studying under his uncle, Stephen Dewey — the husband of his mother's sister — in Prince George County.[5] Dewey was a justice of the peace and served as member of the House of Burgesses.[6]

When reflecting on this experience later in life, Wythe suggested that this apprenticeship was more about clerk work and printing duties than it was about actually learning the practice of law.[7] This lead some scholars to suggest that the experience informed Wythe's commitment to training prospective attorneys differently later in his life, both when he had apprentices and when he became the nation's first law professor.[8] While we do not know the day to day experience that Wythe had while apprenticing under his uncle, we can assume that he would have had access to his uncle's legal library.[9][10]

Contents

Early legal career (1746 – 1754)

It is not until 1745, that there was any law in colonial Virginia on requirements for admission to the legal bar.[11] Wythe becomes licensed under these requirements and admitted to the legal bar in 1746. A copy of Wythe’s law license exists in the order books of Augusta County records and his license was signed by Peyton Randolph, St. Lawrence Burford, Stephen Dewey, and William Nimmo.[12] Once licensed, attorneys could practice in county courts but had to be admitted to each county court that they would practice in. Several county courts admit Wythe in 1746 and 1747, including Elizabeth City and Spotsylvania.[13]

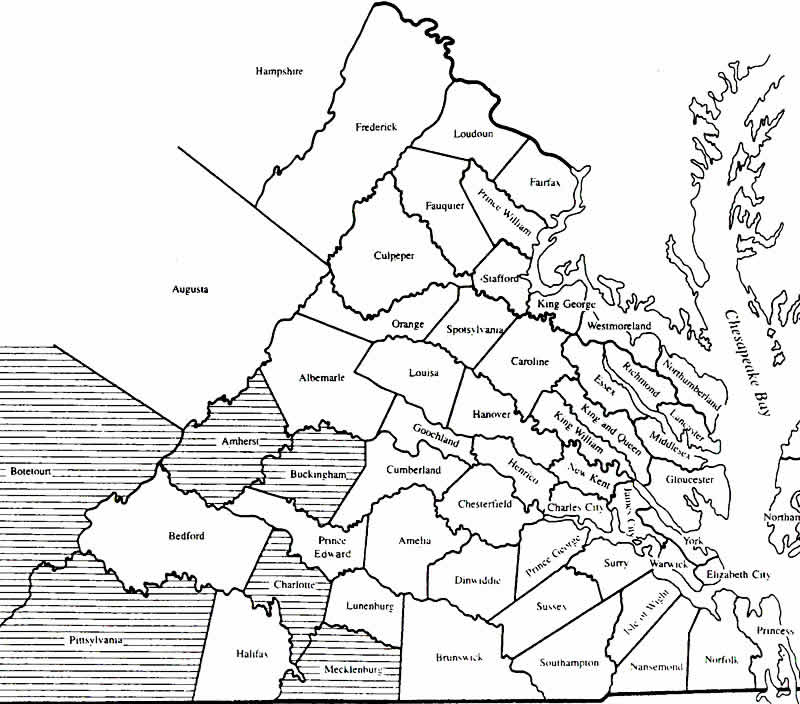

Now, in his early 20s, Wythe moves to western Virginia, specifically to Spotsylvania County. Very quickly, Caroline, Orange, and Augusta Counties admit him to practice.[14] Most county court attorneys rode the circuits in various counties so it is likely that Wythe qualified in other counties in the area, such as Albemarle and Louisa County, but there are no official records.[15] During his time as an attorney in western Virginia, Wythe befriended and worked alongside Zachary Lewis of Spotsylvania, which aided his success as a young lawyer.[16] His case load during this time would have covered a diversity of issues, including criminal, civil, and chancery cases. His time on the western county circuits was likely successful and would have encompassed the vast territory that was western Virginia at the time (including what is today West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin).[17]

Wythe remained a county court attorney in western Virginia until 1748 when he moved back to Williamsburg or the Elizabeth County area.[18] Upon moving back to the capital area, Wythe begins his parallel career as politician when the House of Burgesses selects him to serve as clerk to two standing committees.[19] He stays in this role until the governor appoints him to be interim Attorney General for Virginia in January 1754, while the current Attorney General, Peyton Randolph, was in England to advocate for the Colony to the Crown, through December 1754.[20]

It is assumed that Wythe continued to ride the circuits of nearby counties such as James City, York, New Kent, and Charles City Counties during this time, though we cannot be sure because the court records for these counties have been lost.[21] There is evidence, however, that he was still practicing as a county court attorney in this period because there is record of him arguing at least three cases in Warwick County in 1749.[22] There are also records that he had clients at this time including John Blair in 1751 and the Custis family in 1754.[23] In 1754, Wythe was appointed to the Williamsburg seat in the House of Burgesses and he would provide counsel for candidates in the House of Burgesses that had legal issues within the House.[24]

For the rest of his legal career, Wythe would balance the practice of law with his service in the colonial government.

Pre-Revolutionary attorney (1754 – 1778)

Sometime between 1754 and 1755, the General Court admits George Wythe to practice, ending his time serving on the county court circuit.[25] Between 1755 and 1761, one could not practice in county courts and the General Court unless you were a barrister (a person qualified to practice in an English Court). George Wythe chose to practice in the General Court.[26]

Unlike the county courts, the General Court was a superior court located exclusively in Williamsburg.[27] The General Court handled appellate cases that rose out of county court decisions.[28] Very few attorneys served on this court and at the time Wythe practiced in front of the court he practiced alongside some of the top attorneys in Virginia – including Peyton Randolph, Robert Carter Nicholas, and Edmund Pendleton.[29] One reason scholars have considered attorneys practicing on the General Court as the best of the best is because three attorneys from the court – Wythe, Pendleton, and Nicholas – are immediately elected to high judgeships after the Revolution.[30] Wythe would serve on the General court until the Revolution.[31]

But like most of his life, Wythe kept additional responsibilities while simultaneously licensed in the General Court. He also served as the Elizabeth City County Justice of the Peace in Chesterfield from 1755 until sometime in the 1760s.[32] Likewise, beginning in 1758, Wythe served on the examination board for the General Court and signed licenses for practitioners such as Patrick Henry.[33] Wythe continued serving on this examination board until 1772.[34] Wythe’s political career also accelerated during this period as he served as Interim Attorney General (January 1754-December 1754),[35] William & Mary appointed Burgess (1758-1761),[36] Elizabeth County Burgess Representative (1761-1767),[37] appointed Clerk of the House (1768-1774), Mayor of Williamsburg (1770-1771),[38] and Williamsburg Alderman (? -1772).[39]

Although Wythe was never only practicing law, the legal practice he shared with Robert Carter Nicholas flourished in the 1750s and 1760s.[40] Business records from Elizabeth County suggest that he was financially successful because he could afford to expand his property ownership.[41] He even served as attorney for George Washington twice during this period and again much later in 1773.[42] Even when he was appointed the Clerk of the House in 1768, a time-consuming job, Wythe continued to keep up his practice before the General Court.[43] It was also in the 1760s that Wythe apprenticed his most famous future lawyer, Thomas Jefferson.[44] Jefferson apprenticed under Wythe from 1762-1767.[45]

Once the General Court licensed Jefferson, he joined Wythe in legal practice, and they worked together until the outbreak of the Revolution in 1775.[46] Unfortunately, the General Court records disappeared, but Jefferson was a meticulous note taker, unlike his mentor; thus, most of the records we have on the cases Wythe executed come from Jefferson’s reports during their practice together.[47] For this reason, even though we know Wythe was on the court from 1755-1765 there is very little record of what cases he was a part of, unlike the latter part of his career with Jefferson from 1768-1775.[48] Although not court notes, there is also evidence of petitions in General Court bearing Wythe’s signature or including him as the attorney of record.[49]

Overall, Wythe’s pre-revolutionary career was successful, and he managed to balance both the law and politics until 1775, when all normal legal and political activity ceased due to the Revolution.[50] The General Court has its last session in 1775.[51] Wythe did not know it, but this would lead to the end of his legal career as a practitioner because he was one of the first to be appointed to a high judgeship in 1778 after the Revolution ended.[52]

Wythe’s Legal Reputation

Outside of the specifics of his practice, what do we know about Wythe’s reputation as a lawyer? While most of the evidence is either anecdotal from those who were close to him like Jefferson, or written after his death, it seems that overall Wythe was known and respected as a lawyer of skill and integrity.

Wythe’s presence on the General court sets him apart as one of the most skillful attorneys of the period.[53] It was often said that Wythe had few equals in the courtroom, outside of Edmund Pendleton whom he repeatedly faced in court and who managed to defeat Wythe often.[54] Both lawyers were well respected and continued to compete for over two decades in the General Court.[55] While Wythe was noted to be smarter, Pendleton had a stronger ability to bring forth clever arguments quickly.[56] But this does not mean that Wythe was less skilled than Pendleton. His knowledge of the law was unmatched — “profound” — as noted in an anonymous letter to a local newspaper after his death.[57]

Upon his death, many of his contemporaries noted that Wythe’s integrity was key to his legal practice. One contemporary, Reverend Lee Hassey, stated that Wythe “was the only honest lawyer he ever knew.”[58] Jefferson stated that Wythe was “as distinguished by correctness and purity of conduct in his profession, as he was by his industry & fidelity to those who employed him.”[59] And that the temptations of law never tried succeeded to corrupt Wythe’s purity.[60]

For example, when accepting cases, Wythe was very intentional about who he would and would not represent, never accepting a case simply for financial or reputational gains.[61] As an intake procedure, Wythe required all of his clients to sign affidavits of truth of their testimony and if he later found out they had lied, he would return any money paid and refer them to another attorney.[62]

In a printed eulogy upon Wythe’s death, Mason L. Weems told the story of Wythe withdrawing from a client who he believed to be in the wrong and returned his money because Wythe in good conscious could not go on with the suit. The story alleges that Wythe still maintained lawyer-client confidentiality by telling the client “that as conscience will not allow me to say anything for you, honor forbids that I should say anything against you.”[63] Meaning that while Wythe could not move forward in the case and advised the client not to either, he would not stand in the way of the client finding another attorney. There is no written evidence for this exchange, but as an anecdotal story, it seems to comply with other observations of Wythe’s career from his contemporaries.[64]

Along with his conscientious selection of cases, contemporaries also remembered Wythe to be less concerned about financial success than other attorneys of his day.[65] After his death, public reflections about him as a lawyer stated that he would always take the lowest possible fee. And that no persuasion or subterfuge “could induce him to accept a fee beyond the lowest possible value of his labour.”[66]

Admittedly, these reflections come after Wythe’s death and thus, could be tainted by their desire to remember Wythe at his best. The consistency of the reflections, however, suggest some truth and it could be concluded that at the very least Wythe was known by those who knew him best as a knowledgeable and skillful lawyer who was unmatched in his legal integrity.

County Court cases

Most attorneys in this period practiced in several county courts, referred to as “riding the circuit.”[67] Qualifications for the county courts were set by statute. General Court lawyers examined incoming practitioners and certified their good character in each specific county court they wanted to practice along with paying a 20-shilling fee.[68] While Wythe qualified and practiced in several county courts, the records available for those cases are sparse. The cases below rely primarily on the information printed in Orange County’s order books. We rely on Orange County records because they are one of the only locales that identify the attorney in their reports.[69] Cases listed below that come from a source other than Orange County are marked with a +.

The Wythepedia articles on the county cases briefly summarize the cases and reproduce the filed complaint when available.

General Court cases

Unlike the county courts, the General Court was in one location – Williamsburg. The General Court sessions lasted for four weeks and included original cases as well as appellate cases from county courts. Admission to this court was not set by statute, but existing members had to license future members.[70] Official reports of General Court cases disappeared, but we do have records from notes taken by lawyers who practiced before the court.[71] For information on cases argued by George Wythe, we are in great debt to the writings of Thomas Jefferson.

Most notably, Jefferson published Report of Cases Determined in the General Court of Virginia: From 1730, to 1740; and From 1768, to 1772 in 1829 which contained 42 cases decided in the General Court.[72] For the early years he compiles the manuscript notes written by Sir John Randolph, Edward Barradall, and William Hopkins. Jefferson reported the rest himself.[73] Eight of the cases listed below come from those reports. Additionally, Jefferson kept a written record of these cases and one additional Wythe case in his Household Accounts and Notes of Virginia Court Legal Cases.[74] The Wythepedia articles on these cases include an introduction and summary of the case as well as any known additional information about case arguments and outcomes.

Most of the rest of the cases listed below come from another Jefferson source, Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767-1826. He was a meticulous note taker and kept notes on cases that he worked with Wythe.[75] For those cases, the Wythepedia articles include little information because Jefferson’s memorandum book was a working to-do list, so while it gives case names, attorneys, and sometimes details, it does not provide any information on the outcome or strategy of the cases.

Lastly, there are some records that survive from Wythe’s law firm with Robert Carter Nicholas.[76] We rely on these records for two cases, Carrol v. Clifton and Clifton v. Digges.

- Allen v. Allen

- Anderson v. Anderson

- Archer v. Crawford

- Bland v. Rose

- Beckham v. Philips

- Blackwell v. Wilkinson

- Bolling v. Bolling

- Bradford v. Bradford

- Brent v. Porter

- Brown v. Maupin

- Carrol v. Clifton

- Carter v. Webb

- Cary v. The King

- Clifton v. Diggs*

- Cloyd v. Cloyd

- Cole v. Leigh

- Cole v. Robertson*

- Custis v. West

- Dalton v. Lyons

- Godwin v. Lunan

- Hardaway v. Bland

- Harris v. Jefferson

- Herndon v. Carr

- Hite v. Fairfax

- Hooker v. Burwell

- Howell v. Netherland

- Hudson v. Hudson

- Hunter v. Glassell

- Id. v. Jno Black

- Jefferson v. Stith

- Jefferson v. Fleming’s exrs.

- Jefferson v. Skipwith

- Mercer v. Wayle’s exrs.

- Mills v. Hayes

- Phillips v. Hubbard

- Quarles v. Gregory

- Spiers v. Thomas

- Stephens v. Cabage

- Thornton v. Hunter

- Turnstall v. Hunt

- Turpin v. Goode

See also

References

- ↑ Source Material on George Wythe is hard to come by. See Kirtland, George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge (New York: Garland, 1986).

- ↑ Frank L. Dewey, Thomas Jefferson Lawyer (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1987), 3.

- ↑ Kirtland, 36-37.

- ↑ William Edwin Hemphill, "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia," 34 (citing the History of the College of William and Mary from its Foundation, 1660 to 1874, 84).

- ↑ Kirtland, 40; see also Dewey, 3.

- ↑ See Hemphill, 36. Both positions Wythe would later also hold.

- ↑ Hemphill, 37; Kirtland, 40-41.

- ↑ Hemphill, 38.

- ↑ Hemphill, 38.

- ↑ Kirtland, 40-41.

- ↑ Hemphill, 41 (citing Henning Statutes).

- ↑ Hemphill, 42 (citing entry of May 21, 1747, Order Book No. 1, 196, Augusta County Records.

- ↑ Hemphill, 42. For record of Elizabeth County admission see June 18, 1746, minutes in Order Book, 1731-1747, 489, Elizabeth County Records. For Spotsylvania County admission, see November 4, 1746, Orders, 1738-1749, 395, Spotsylvania County Records; see also Kirtland, 42.

- ↑ Hemphill, 43-46 (qualified in Carolina County in February of 1747 and Augusta/Staunton in May of 1747); see also Kirtland, 42.

- ↑ Hemphill, 45.

- ↑ Zachary Lewis also becomes Wythe's father-in-law. Horace Edwin Hayden, Virginia Genealogies (Wilkes-Barre, PA: E.B. Yordy, 1891), 381-382.

- ↑ Hemphill, 48-49.

- ↑ There is some speculation that Wythe moves back home because of the death of his first wife, Ann Lewis. Hemphill, 52.

- ↑ Hemphill, 55.

- ↑ Hemphill, 66-71.

- ↑ Hemphill, 55.

- ↑ Hemphill, 55 (citing entries of April 6, 1749, Minutes, 1748-1762, 29-31, Warwick County Records).

- ↑ Hemphill, 56-57. For John Blair see entries of March 20, 22, October 2, November 7, 1751, William and Mary College Quarterly 1st Series, VII, 137, VIII, 5, VII, 146, 148; for Custis family see letter from Wythe to Daniel Parke Custis, April 10, 1754).

- ↑ Hemphill, 57.

- ↑ The exact date of his appointment is unclear, but Hemphill argues that it was likely sometime before May 1755 because there is a license signed by Wythe for Paul Carrington in 1755, which would have required that Wythe have a license in the General Court. See Hemphill, 77 (citing 1755 license for Paul Carrington).

- ↑ Kirtland, 45; Dewey, 2,4.

- ↑ Dewey, 3.

- ↑ Kirtland, 45.

- ↑ Hemphill, 84.

- ↑ Dewey, 7.

- ↑ Kirtland, 45.

- ↑ Hemphill, 75 (citing Order Book, 1775-1776, Elizabeth City County Records).

- ↑ Hemphill, 106 (citing Tyler’s Quarterly Magazine, IX, 97). Also signed the licenses of Peter Hog. Hemphill, 106 (citing Brock, ed., Records of Dinwiddie, I, 470, n.); Dewey, 118.

- ↑ Hemphill, 105; Dewey, 118.

- ↑ Kirtland, 46.

- ↑ Hemphill, 166-167.

- ↑ Hemphill, 170.

- ↑ Hemphill, 258 (citing Virginia Gazette, pub. By Pudie and Dixon, December 3, 1772); Kirtland, 49.

- ↑ Hemphill, 258.

- ↑ Hemphill, 258.

- ↑ Hemphill, 104.

- ↑ Hemphill, 102 (citing Robert Carter Nicholas to George Washington, January 5, 1758, Stanislaus Murray Hamilton, ed., Letters to Washington and Accompanying Papers, II, 256; Entries of April 1 and May 21, 1760, John C. Fitzpatrick ed., The Diaries of George Washington, 1748-1799, I, 147, 163). For later representation see Hemphill, 137 (citing George Wythe to George Washington, December 15, 1773, Hamilton, ed., Letters to Washington, IV, 282-284; George Washington to George Wythe, January 17, 1774, Fitzpatrick, ed., Writings of Washington, III, 174-176; George Washington to John Parke Custis, May 26, 1778, Fitzpatrick, ed., Writings of Washington, XI, 456)

- ↑ Kirtland, 96 (stating that Wythe’s duties as clerk “were not so arduous as to preclude Wythe’s practice before the General Court”).

- ↑ Hemphill, 114. Jefferson was not the only legal student apprenticed by Wythe at this time. There were others including St. George Tucker. See Hemphill, 146; Kirtland, 97.

- ↑ Hemphill, 124.

- ↑ Hemphill, 124 (citing “Autobiography,” Berg. ed., Writings of Jefferson, I, 4). For General court closing see Hemphill, 149.

- ↑ See Thomas Jefferson, Reports of Cases Determined in the General Court of Virginia from 1730 to 1740 and from 1768 to 1772 (Buffalo, NY: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1981); see also Hemphill, 130-132; Kirtland, 96.

- ↑ Hemphill, 10

- ↑ See Hemphill, 144 (citing Petition of Achilles Foster, undated, Autograph Collection of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery; Petition of Solomon Redmon, undated [ca.1772], in the possession of Thomas F. Hadigan Co., New York, December 1936; Petition of John Randolph, February 12, 1773, Gratz Collection, Pennsylvania Historical Society Library).

- ↑ Kirtland, 97-98.

- ↑ Hemphill, 149.

- ↑ Kirtland, 119.

- ↑ Dewey, 7; Kirtland, 49.

- ↑ Kirtland, 49-51, 59; see also Hemphill, 98.

- ↑ Hemphill, 159.

- ↑ Hemphill, 159-161.

- ↑ Hemphill, 150 (citing Anonymous “Communication,” The Enquirer, June 10, 1806).

- ↑ Hemphill, 153 (citing J.T. Stoddert, letter to Bishop Heade, reprinted in Heade, op. cit., II, 238).

- ↑ Hemphill, 154 (citing Jefferson, “Notes for the Biography of George Wythe,” Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress).

- ↑ Hemphill (citing Randolph, Manuscript History of Virginia, Virginia Historical Magazine, XLIII, 131).

- ↑ Hemphill, 154.

- ↑ Hemphill, 154-155 (citing “Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire,” The American Gleaner and Virginia Gazette, I, 2-3); see also Kirtland, 58.

- ↑ Hemphill, 155-156 (citing a reprint from The Charleston, S.C., Times, July 1, 1806, in William and Mary College Quarterly, 1st Series, XXV, 18-19.

- ↑ Hemphill, 157.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid, (citing “Communication” signed “A.B.” Virginia Gazette, and General Advertiser, June 18, 1806).

- ↑ Dewey, 1.

- ↑ Dewey, 4.

- ↑ Hemphill, 46-47. There is also evidence that indicates Wythe pleaded more cases in Orange County than any other advocate except Zachary Lewis. Hemphill, 48.

- ↑ Dewey, 2-4.

- ↑ Kirtland, 96; Hemphill, 130.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, Report of Cases Determined in the General Court of Virginia: From 1730, to 1740; and From 1768, to 1772 (Charlottesville: F. Carr, and Co., 1829), (Buffalo, New York: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1981 ed.).

- ↑ Jefferson Reports, Introduction to the 1981 edition.

- ↑ Household Accounts and Notes of Virginia Court Legal Cases. Thomas Jefferson Papers, 1606 to 1827, Series 7: Miscellaneous Bound Volumes, Library of Congress.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, Volumes I-II: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767-1826. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 2nd Series, James A. Bear, Jr. and Lucia C. Stanton, eds. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson and Jefferson-Randolph Family Papers, 1747-1827, in the Tracy W. McGregor Library, Accession #564, 6746, Albert H. and Shirley Small Special Collections Library (Charlottesville, Va: University of Virginia).

External links

- "County Formation during the Colonial Period," Encyclopedia Virginia.