"Chancellor Wythe's Death"

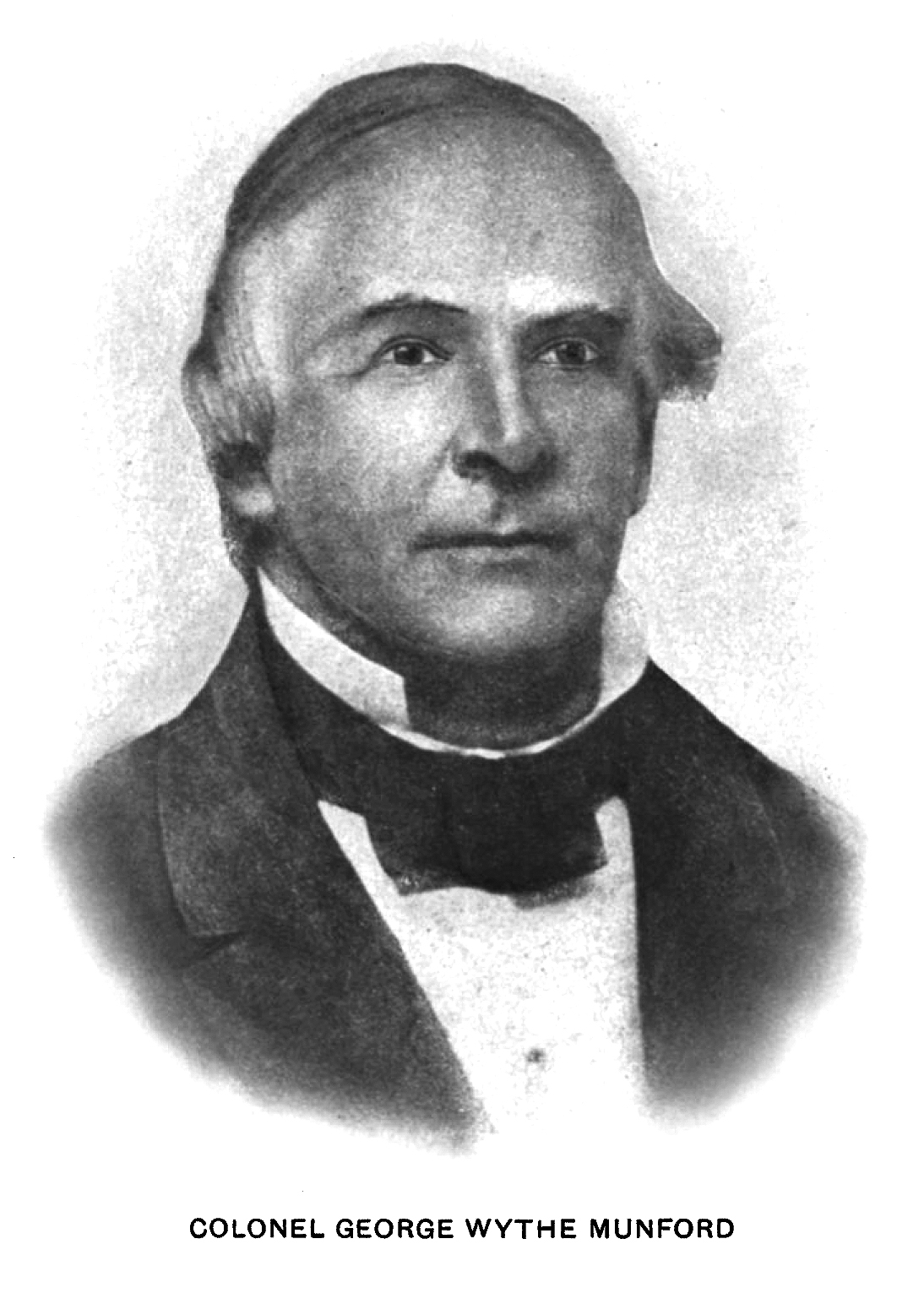

Colonel George Wythe Munford (1803 – 1882), the author of The Two Parsons, was the son of William Munford. The younger Munford was born in Richmond, Virginia, and named for his father's friend and mentor, George Wythe. Munford graduated from the College of William & Mary with a Bachelor of Arts, and afterwards was employed by his father, who was serving as clerk of the House of Delegates of Virginia. After his father's death in 1825, Munford was elected to replace him in the post of clerk, despite being only twenty-two years old. At the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829-1830, Munford was selected to be secretary. In 1852 he became Secretary of the Commonwealth, an office he held for twelve years. He was tasked with revising the Code of Virginia in 1860, and with publishing the Code of 1873. He co-signed the Proclamation of Secession on June 14, 1861. In 1863, his name was proposed as a candidate for Governor of Virginia. Munford was married twice, in 1828 and in 1838, and two of his sons were killed during the Civil War. Retiring to Gloucester County, Virginia, Munford died in 1882 and was buried in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond.[1]

The Two Parsons was published two years after Munford's death, in 1884, collected with Cupid's Sports, The Dream, and The Jewels of Virginia. The Two Parsons consists of a series of humorous anecdotes, often with religious or moral lessons, regarding Munford and his two friends, Parson Buchanan and Parson Blair, during their time spent in Williamsburg and Richmond.[2] Chapter 28 deals entirely with "Chancellor Wythe's Death,"[3] including a description of Wythe at the time he resided in Richmond, a second-hand account of the Chancellor on his death bed, and the details of Wythe's funeral and the proceeding murder trial. Another anecdote concerning Wythe is "Parson Blair's Snack—Chancellor Wythe."

Julian P. Boyd, in his 1955 essay "The Murder of George Wythe", makes a point of the significance of The Two Parsons, which, despite its errors and exaggerations, remains 'the only published account in the nineteenth century, aside from the contemporary comment of the Enquirer,[4] which discusses [the] legal technicality of Negro evidence and the only one (save that of Clay) which rejects the theory of Wythe's accidental death.'[5]

Chapter XXVIII text

Page 414

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHANCELLOR WYTHE'S DEATH.We have carried our Parsons and to places not usually frequented by men of their cloth. We have described them as they appeared in their day. If there was anything objectionable in their conduct, let those who think so draw a moral from it, and teach those who agree with them to avoid the evil. The characters of men should be described with truthfulness. Let the evil be avoided; let the good be imitated. For our own part, we admire them for the common sense they displayed, for placing themselves in positions where the good they might do overbalanced the appearance of evil.

The bedside of the sick and dying is a position recognized by all as appropriate for a minister. However hardened the sinner, however vile the reprobate, he may be successfully approached at a time like this by good men, and they may indulge even in reproof without incurring censure or violating decorum. The thief on the cross was forgiven. A word dropped in season—a prayer elicited from the reprobate's heart—may perchance save a perishing soul. The heart is generally softened by the rackings and pains of disease, and a lodgment may then be made which may cause that garrison of many devils to see the folly of mortal combat with its Creator, and cause an unconditional surrender. Even though repentance may be extorted by fear, there is cause for rejoicing. But when a pious minister approaches the bed of a believer, and

Page 415

witnesses his resignation and submission, and willingness to rely implicitly upon divine mercy, through the mediation of a crucified Redeemer, there is a calm pleasure to the sick, and a delight to those around him which no Christian can fail to appreciate.

We have spoken of Chancellor George Wythe in a previous chapter,[6] and as we are going to his bedside, we cannot refrain from making reference to his estimable character. In the times that tried men's souls there was no occasion for this; for he was one of the magnates who occupied such a large space in the public eye that all men knew his position and services.

As a chancellor, in his court-room, in the basement of the Capitol, which was rarely occupied by more than a few members of the bar and a few suitors, without insignia of office and only his innate dignity to support him, men might transact their business without reflecting upon the inestimable value of a judge uncontaminated by prejudice or partiality, or meaner selfishness, upon whose pure decision their property depended. They knew he held the even scales of justice well balanced in his hands, and that nothing but undoubted equity and law could turn those scales to the right or the left; still, no outward demonstration of more than ordinary respect was ever exhibited. In these days, when it is not uncommon to hear notable contrasts drawn between some unworthy judges, who have soiled the judicial ermine, and brought their decisions and illegal acts into disrepute and themselves into contempt, it may not be considered useless to revive some incidents in the life and character of such a man as George Wythe, and hold him up as an exemplar of a patriot, jurist, and pure Virginian. It is a pleasure for us to dwell for a moment upon the personal appearance of this remarkable man.

He was one of those that a child could approach with-

Page 416

out hesitation or shrinking,—would talk to, in its innocent prattle, without constraint or fear,—would lean upon, and, looking in his face, return a sympathetic smile. He was one of those before whom a surly dog would unbend, and wag his tail with manifest pleasure, though never seen before. Animals and children are guided in their affections or dislikes by countenance and the manner.His stature was of middle size. He was well-formed and proportioned; and the features of his face many, comely, and engaging. In his walk, he carried his hands behind him, holding the one in the other, which added to his thoughtful appearance. In his latter days he was very bald. The hair that remained was uncut, and worn behind, curled up in a continuous roll. His head was very round, with a high forehead; well-arched eyebrows; prominent blue eyes, showing softness and intelligence combined; a large aquiline nose; rather small, but well-defined mouth; and thin whiskers, not lower than his ears. There were sharp indentations from the side of his nose down on his cheek, terminating about an inch from the corner of the mouth; and his chin was well-rounded and distinct. His face was kept smoothly shaven; his cheeks, considerably furrowed from the loss of teeth; and the crow's feet very perceptible in the corners of his eyes. His countenance was exceedingly benevolent and cheerful.

His dress was a single-breasted black broadcloth coat, with a stiff collar turned over slightly at the top, cut in front Quaker fashion; a long vest, with large pocket-flaps and straight collar, buttoned high on the breast, showing the ends of the white cravat that filled up the bosom. He wore shorts; silver knee and shoe buckles; was particularly neat in his appearance, and had a ruddy, healthy hue. He had a regular habit of bathing, winter and summer, at sunrise. He would put on his morning

Page 417

wrapper, go down with his bucket to the well in the yard, which was sixty feet deep and the water very cold, and draw for himself what was necessary. He would then indulge in a potent shower-bath, which he considered the most inspiring luxury. With nerves all braced, he would pick up the morning Enquirer, established about two years before, and seating himself in his arm-chair, would ring a little silver bell for his frugal breakfast. This was brought in immediately by his servant woman, Lydia Broadnax, who understood his wants and his ways. She was a servant of the olden time, respected and trusted by her master, and devotedly attached to him and his—one of those whom he had liberated, but who lived with him from affection. He was born in the county of Elizabeth City, on the shores of the Chesapeake , in 1726, and inherited an estate ample for ease and independence. Though his education was defective in his youth, yet, by close application, in after life he had become an accomplished Latin and Greek scholar, and possessed a fair knowledge of the modern languages. In writing to friends who were versed in those languages, even in ordinary letters or notes, he often mingled sentences, first in one and then in the other language, which made his correspondence very entertaining. After he reached his four score years he was studying Hebrew, and with the aid of a Rabbin by the name of Seixas,[7] a learned Jew, who then lived in Richmond, had made sufficient progress to enable him to read the Bible with much ease in the original. He said he preferred to read it for himself, untrammelled by commentators or disputants over its translation. When a difficulty arose in his mind he investigated the matter by the original Hebrew, examined it in connection with the Greek, weighed the evidence for and against, as he would in a difficult case before him in court, and draw his own

Page 418

conclusions, his sole object being to arrive at the truth. He was a profound civil lawyer, a rhetorician, grammarian, and logician, and possessed a fair knowledge of mathematics, as well as of natural and moral philosophy. He lived in the practice of the most rigid and inflexible virtue, and was a pattern of temperance and frugality.He was a widower; had been twice married: first to a daughter of John Lewis,[8] with whom he studied law; secondly, to Miss Taliaferro, residing in the neighborhood of Williamsburg. He had only one child, which died in infancy. Though his name was not perpetuated by his own issue, yet all over Virginia, from the love and esteem borne him, there are many George Wythes, and the name will be handed down through untold generation. As a lawyer he possessed one distinguishing trait, he invariably refused business when he believed the justice of the case was against the client. As a judge he was remarkable for the most scrupulous impartiality, rigid justice, unremitting assiduity, and pure disinterestedness. The offices he filled, and the public duties he performed, are recorded in all the histories and chronicles of the great men of Virginia. We are dealing with his private character.

His benevolent disposition was apparent to all. Unassuming modesty, simplicity of manner, and great equanimity of temper were distinguishing characteristics throughout his life. He emancipated his slaves, but did not cast them on the world friendless and needy. He gave them sufficient sums to free them from want, and his own example had taught them to cultivate industrious habits. He taught one of his negro boys Latin and Greek, and the rudiments of science. This boy, however, died before his benefactor. he bequeathed a large portion of his property, in trust, to support his three freed negroes, a woman, a man, and a boy, during their lives. he had written his will, leaving the greater portion of his pro-

Page 419

- Main article: Last Will and Testament

perty to George Wythe Sweeny, the grandson of his sister, his own grand nephew; but circumstances occurring not long before and immediately preceeding his death induced him to revoke this portion of his will, and leave the bulk of his estate to others.This will being a remarkable document in itself, and exhibiting some traits of the Chancellor's character, which we have endeavored to portray, is given here in full.

HIS WILL. "Contemplating that event, which one in the second year of this sixteenth lustrum may suppose to be fast approaching, at this time, the twentieth day of April in the third year of the nineteenth centurie since the Christian epoch, when such is my health of bodie that vivere amem, and yet such my disposition of mind that, convinced of this truth, what supreme wisdom destinateth is best, obeam libens, I, George Wythe of the city of Richmond, declare what is herein after written to be my testament, probably the last: appointing my friendly neighbor, William Duval, executor, and desiring him to accept fifty pounds for his trouble in performing that office over a commission upon his disbursements and receipts inclusive, I devise to him the houses and ground in Richmond which I bought of William Nelson, and my stock in the funds, in trust, with the rents of one and interest of the other to support my freed woman Lydia Brodnax and my freed man Benjamin, and freed boy Michæl Brown, during the lives of the two former, and after their deaths in trust to the use of the said Michael Brown; and all the other estate to which I am and shall at the time of my death be entitled, I devise to George Wythe Sweeney, the grandson of my sister.

"GEORGE [L.S.] WYTHE."

Page 420

Three years afterwards he appended to the foregoing the following codicil."I, who have hereunder written my name, this nineteenth day of January in the sixth year of the before mentioned centurie, revoke so much of the proceeding devise to George Wythe Sweney as is inconsistent with what followeth. The residuary estate devised to him is hereby charged with debts and demands. I give my books and small philosophical apparatus to Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States of America,—a legacie, considered abstractlie, perhaps not deserving a place in his museum, but, estimated by my good will to him, the most valuable to him of any thing which I have power to bestow. My stock in the funds before mentioned hath been changed into stock in the bank of Virginia. I devise the latter to the same uses, except as to Ben, who is dead, as those those to which the former was devoted. To the said Thomas Jefferson’s patronage I recommend the freed boy, Michael Brown, in my testament named, for whose maintenance, education or other benefit, as the said Thomas Jefferson shall direct, I will the said bank stock, or the value thereof, if it be changed again, to be disposed. And now, good Lord, most merciful, let penitence—

Sincere, to me restore lost innocence;

In wrath my grievous sins remember not;

My secret faults out of thy record blot;

That after death’s sleep, when I shall awake,

Of pure beatitude I may partake"GEORGE WYTHE [SEAL.]"

"I will that Michael Brown have no more than one half my Bank Stock, and George Wythe Sweeney, have the other immediatelie.

Page 421

"I give to my friend, Thomas Jefferson, my silver cups and gold headed cane, and to my friend William Duval, my silver ladle and table and teaspoons."If Michael die before his full age, I give what is devised to him to George Wythe Sweeney. I give to Lydia Brodnax my fuel. This is to be part of my will, and as if it were written of the parchment inclosed with my name in two places.

"G. Wythe [SEAL.]"24th February, 1806.

Subsequent to the writing of the last codicil, dated the 24th of February, 1806, the Chancellor had ascertained from various sources that his nephew had become exceedingly dissipated—was habitually keeping company with disreputable associates and frequenting gambling houses. From time to time, as opportunity occurred,—which was not often, because he evidently avoiced his uncle's society,—he had told him that such accounts had reached his ears, and in gentle reproof had warned him that such conduct could not be tolerated. He went so far as to say that he had made provision for him in his will, but unless there was some change in his conduct he should certainly revoke his bequest. His mind was finally made up to this by learning from one of the bank officers that Sweeney was suspected of having forged the Chancellor's name to two checks on the Bank of Virginia, one for fifty and another for one hundred dollars. There was a probability that he would be indicted before the grand jury for the forgeries, and the old gentleman came to the conclusion that he must do this thing which hung so heavily over him. He put it off, however, from day to day.

Such was the condition of affairs when Parson Buchanan came one morning to Parson Blair's house, and knocked excitedly at the door. The Parson answered

Page 422

the knock in person, and seeing his friend, said in a cheerful tone, "What are you kicking up this rumpus about?""I have heard that Chancellor Wythe is very ill," answered he, "and it is thought he has been poisoned. I want you to accompany me to his house."

"Poisoned!" said the good man. "I saw him but a day or two ago, and he was uncommonly well and cheerful. Who could have perpetrated such a deed?"

"I hear it was his own nephew, George Wythe Sweeney. Dr. Foushee called at my office and asked me to go to the old gentleman, and I want you to go also. The Doctor has been to see him twice already,—the last time in consultation with Dr. McCaw,—and they concur in the opinion that he is extremely ill. He said, moreover, that the Chancellor's old cook, Lydia, was also sick, and that the boy, Michael, who lived with them, was affected in the same manner. Lydia's story, to use her own language, was that 'Mass George Sweeney came here yesterday, as he sometimes does when old master is at court, and went into his room, and finding his keys in the door of his private desk, he opened it, and when she went in, she found him reading a paper that her old master had her was his will. It was tied with a blue ribbon. Mass George said his uncle had sent him to read that paper, and tell him what he thought of it. Then he went away, and, after the Chancellor had gone to bed, came back again late at night, and went to the room he always stays in when he sleeps here. In the morning, when breakfast was nearly ready, he came into the kitchen, and said, 'Aunt Lydy, I want you to give me a cup of coffee and some bread, because I haven't time to stay to breakfast.' She said, 'Mars George, breakfast is nearly ready; I have only to poach a few eggs, and make some toast for old master; so you had better stay and eat

Page 423

with him.' 'No,' he said, "I'll just take a cup of hot ooffee now, and you can toast me a slice of bread.'"He went to the fire, and took the coffee-pot to the table, while I was toasting the bread. He poured out a cupful for himself and then set the pot down. I saw him throw a little white paper in the fire. He then drank the coffee he had poured out for himself, and ate the toast with some fresh butter. He told me good-bye and went about his business. I didn't think there was anything wrong then.

"In a little while I heard old master's bell. He always rings it when he is ready for his breakfast; so I carried it up to him. He poured out a cup of coffee for himself, took his toast and eggs, and ate and drank while he was reading the newspaper.

"'Lyddy,' said he, 'did I leave my keys in my desk yesterday, for I found them there last night?'

"I suppose so, master, for I saw Mars George at the desk reading that paper you gave me to put there, and which you said was your will. He said you had sent him to read it, and to tell you what he thought of it.

"Master said, 'I fear I am getting old, Lyddy, for I am becoming more and more forgetful every day. Take these things away, and give Michael his breakfast, and get your own, Lyddy.'

"I gave Michael as much coffee as he wanted, and then I drank a cup myself. After that, with the hot water in the kettle I washed the plates, emptied the coffee-grounds out and scrubbed the coffee-pot bright, and by that time I became so sick I could hardly see, and had a violent cramp. Michael was sick, too; and old master was as sick as he could be. He told me to send for the doctor. All these things makes me think Mars George must have put something in the coffee-pot. I didn't see him, but it looks monstrous strange."

Page 424

"The doctor said, after hearing this statement, which the woman had also made to her master, they were satisfied poison had been placed in the coffee by the nephew."The doctor further said the Chancellor had told him he ate nothing but two eggs and some toast, and drank a cup of coffee; that in a very short time he had been taken with severe pains, followed by nausea. He was complaining of great thirst, dryness of the throat and mouth, restlessness, and anxiety. Moreover, he had found the woman, Liddy, not so ill, but seriously sick; and the boy, Michael, worse than either-cold in his extremities and having convulsions. These symptoms proved to his satisfaction that arsenic had been put in the coffee; and from the rapidity of its effect he was satisfied a large quantity had been administered.

"From the urgency of the cases the doctor had thought it advisable to have assistant medical aid, and had called in Dr. McCaw; but he thought the boy, Michael, would die, and did not think the Chancellor was by any means safe."

With this information, our two friends, with melancholy hearts, wended their way to the Chancellor's house, where they found Mr. Munford. The old gentleman was suffering intense agony, complaining of excessive heat, accompanied by occasional spasms. In the intervals of pain he was calm and composed, but said he felt his end was approaching. He extended his hands to the good Parsons, and gave to each a kind pressure of recognition; and when asked how he felt, said that a man of his age could not endure such intense suffering and live long; that the remedies his physicians had administered had as yet afforded him no permanent relief. He said he had no fear of death, but regretted the manner in which it had been brought about. It would be a stigma on his own name, and a

Page 425

deep and lasting mortification to his sister, for whom he entertained the warmest affection. He knew his nephew had been wild and dissipated, but he had not realized his depravity. He had thought he bad a warm heart and a strong attachment for himself. He had intended the bulk of his fortune for him, but he would be compelled now to revoke that intention.He then turned to Mr. Munford, and said, "For particular reasons, I desire my friend, Edmund Randolph, to write the codicil, and must ask you to request his attendance here at his earliest convenience." Of course this request was immediately attended to.

It was evident the Chancellor had not mistaken his condition, for there were already symptoms of great weakness and a manifest change in his appearance. Nevertheless, he smiled kindly, and turning to our Parsons, again extended his hand, first to one and then to the other. He said no visit could have gratified him more. "It was a pleasure to have two such men smoothing his pillow and giving him words of comfort at such a time."

" There is a better friend than either of us," said Parson Buchanan; "He has gone before to prepare mansions for us in a better home than this."

"He is the staff that will not break, nor pierce the hand that leans upon it," said Parson Blair.

"Ah, yes!" said the Chancellor. "This is my consolation." He raised his eyes to heaven, and his lips moved in an audible petition to the Almighty.

Then Parson Buchanan said, "'Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.' And with your permission, my old friend, we will unite with yon in prayer." And kneeling, all heartily joined in the prayer for the sick and dying. When he had finished, the Chancellor again took his hand and

Page 426

pressed it most feelingly. He then extended it to Parson Blair, and said, "We will meet hereafter, around the throne of grace, where pain and sorrow shall be felt no more."Dr. Foushee came to the door. The Chancellor beckoned to him, and said, almost in a whisper, "How are Lyddy and Michael?"

"Lyddy," said the doctor, "feels more comfortable. But Michael is dead. The effect of the poison has been rapid indeed."

"I shall not be far behind," the Chancellor said. He uttered a groan, and tossed to and fro in visible agony. As our Parsons prepared to leave him, seeing he was too ill for them to be of any service, they said, "We hope to see you again. God be with you."

"Not in this world," said he, and they passed out sorrowing. As they left, Dr. McCaw entered. The two doctors went to the window. A few words only were interchanged. They administered some antidote, and then waited for the paroxysm to pass off.

An hour or two elapsed, during which the Chancellor dozed. Then Mr. Edmund Randolph, one of the best lawyers of that day, and the Chancellor's steadfast friend, gently came into the room, and finding him awake, received full instructions from the Chancellor as to the codicil he desired him to write.

It would be useless for us to enter into the minutiæ of the preparation of this codicil. But we give it in full after its execution to show what were the testator's wishes, and how they were carried into effect. We add what he said to Mr. Munford and Mr. Randolph after its execution:

"It is not my desire that this unfortunate nephew of mine shall be prosecuted or punished, further than this codicil will punish him, for the offences with which he

Page 427

stands charged. I dread such a stigma being cast upon my name or my sister's. I do not believe he can be convicted in the teeth of our statute law, which prohibits negro testimony from being received against a white man, under trial. And without such testimony he will be acquitted. For myself, I shall die leaving him my forgiveness."This will explain the reason why Edmund Randolph appeared as counsel for the defence, when Sweeney was arrested and tried.

The codicil is as follows:

"In the name of God. Amen.

"I, George Wythe, of the city of Richmond, having heretofore made my last will, on the twentieth of April, in the third year of the nineteenth century since the Christian epoch, and a codicil thereto on the nineteenth of January, in the sixth year of the aforesaid century, and another codicil on the 24th February, 1806, do ordain and constitute the following to be a third codicil to my will; hereby revoking the said will and codicils in all the devises and legacies in them, or either of them contained, relating to, or in any manner concerning George Wythe Sweeney, the grandson of my sister; but I confirm the said will and codicils in all other parts, except as to the devise and bequest to Michael Brown, in the said will mentioned, who I am told died this morning, and therefore they are void. And I do hereby devise and bequeath all the estate which I have devised or bequeathed to the said George Wythe Sweeney, or for his use, in the said will and codicils, and all the interest and estate which I have therein devised or bequeathed in trust for or to the use of the said Michael Brown, to the brothers and sisters of the said George Wythe Sweeney, the grandchildren of my said sister, to be equally divided among them, share and share alike. In testimony whereof

Page 428

have hereunto subscribed my name and affixed my seal, this first day of June, in the year 1806."G. WYTHE, [SEAL.]"Signed, sealed, published and declared by the said George Wythe, the testator, as and for his last will and testament in our presence; and at his desire we have hereunto subscribed our names as witnesses, in his presence and in the presence of each other."

(The interlineations of the words, "and another codicil on the 24th of February, 1806, "and of the words" will and codicils" and "grand" being first made, and the whole being distinctly read to the testator before the execution of this codicil.)

- "EDM. RANDOLPH.

- "W M. PRICE.

- "SAMUEL GREENHOW.

- "SAML. MCCRAW."

The foregoing will and codicil are written upon parchment by the testator in the handwriting of Edmund Randolph.

The original envelope which enclosed the will and codicils is evidently written by the testator himself:

"To WILLIAM DUVAL. To be opened when G. Wythe shall cease to breathe, unless by him required before that event."

The Chancellor lingered from day to day, far beyond the expectation of his physicians and friends. Michael had been buried, and Lydia had recovered. Our Parsons had regularly repeated their visits, and aided somewhat in reviving his spirits, and keeping alive the flickering flame of life slowly sinking in its socket.

They called for the last time on the morning of the 8th of June, hoping against hope to find him better; but

Page 429

- Main article: Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806

he was too far gone to recognize them, and in a short time he was numbered with the dead.He died in the eighty-first year of his age, and was buried on Monday, the 9th of June, 1806, in the burial ground attached, to St. John's Church, in the city of Richmond. There is no monument or other mark to designate the spot where his remains repose; but it is believed he was buried on the west side of the church, near the wall of that building.

There were at that period only two newspapers published in the city, the Virginia Argus and the Richmond Enquirer, and they were only published semi-weekly. They did not appear until the 10th of June. Each of them published the action of the executive council, which, though it was Sunday, met on that day, and entered the following order:

"COUNCIL CHAMBER, June 8, 1806."Preparatory to the internment of George Wythe, late Judge of the High Court of Chancery for the Richmond District, a funeral oration will be delivered at the Capitol, in the Hall of the House of Delegates, to begin precisely at 4 o'clock P. M. on to-morrow; after which the procession will commence in the following order: The Clergymen and Orator of the Day.—Coffin, with the word 'Corpse' on the lid.—Physicians.—The Executor and Relations of the Deceased.—The Judges.—Members of the Bar.—Officers of the High Court of Chancery. The Governor and Council.—Other officers of Government.—The Mayor, Aldermen and Common Council of the City of Richmond.—Citizens."

The Enquirer adds: "Need it be said that the crowd which assembled in the Capitol was uncommonly numerous and respectable? After the delivery of a funeral oration by Mr. William Munford, a member of the Exe-

Page 430

- Main article: Notes for the Biography of George Wythe

cutive Council, the procession set out towards the church. It is no disparagement to the virtues of the living to assert that there is not, perhaps, another man in Virginia. whom the same solemn procession would have attended to the grave. Let the solemn and lengthened procession which attended him to his grave declare the loss which we have sustained."A doubt has been expressed whether the Chancellor was buried in the cemetery attached to St. John's Episcopal Church in Richmond. After reading these notes on the procession no doubt exists in our mind. The words, "Preparatory to the interment," in the order of council, and "the procession set out towards the church," and "attended to his grave," in the narrative in the Enquirer, are conclusive.

Thus ended the career of no common man. Mr. Jefferson says: "His virtue was of the purest kind; his integrity inflexible and his justice exact; of warm patriotism, and devoted as he was to liberty and the natural and equal rights of man, he might truly be called the Cato of his country, without the avarice of the Roman; for a more disinterested person never lived. Temperance and regularity in all his habits gave him general good health, and his unaffected modesty and suavity of manners endeared him to everyone. He was of easy elocution; his language chaste; methodical in the arrangement of his matter, learned and logical in the use of it, and of great urbanity in debate; not quick of apprehension, but with a little time profound in penetration and sound in conclusion."[9]

After the first shock had subsided to which the public mind was subjected by the death and burial of such a truly great man, the attention of the law-abiding community was attracted to him who had been guilty of such an atrocious crime. We find it chronicled in the papers of

Page 431

the day, that on the 23d of June, 1806, George Wythe Sweeney was called before the examining court of this city on the charge of poisoning his uncle, the venerable George Wythe, and a servant boy. It is stated that he was unanimously remanded to jail for further trial before the district court, to be held in the following September.The proceedings before that court are subsequently referred to, as follows:

"The District Court met in this city on Monday, the 1st of September, 1806. Present: Judges Prentis and Tyler. On Tuesday came up the celebrated trial of George Wythe Sweeney on the charge of administering arsenic to his great uncle, the venerable George Wythe.

"Philip N. Nicholas (Attorney-General) for the prosecution, and William Wirt and Edmund Randolph counsel for defendant. After an able and eloquent discussion, the jury retired, and in a short time brought in the verdict of not guilty.

"A similar indictment against him for poisoning Michael, a mulatto boy, who lived with Mr. Wythe, was quashed without a trial.

"Some of the strongest testimony which had been presented before the called court and the grand jury was excluded from the petit jury, because it was gleaned principally from the evidence of negroes, which, by the statute law of the State, could not be used against a white man.

"On a subsequent day of the same court the prisoner was brought up for trial on two indictments found against him for counterfeiting his uncle's name to checks drawn upon the Bank of Virginia.

"The indictment consisted of two counts. The first charged that the prisoner presented, on the 27th of May, 1806, a check on the Bank of Virginia for the sum of one hundred dollars, which was accompanied by a forged

Page 432

letter, directing the cashier of the bank to pay the said check, the letter and check purporting to have been written by George Wythe. The second count charged that the money was obtained by a false, feigned, and counterfeit token to the similitude and likeness of a true check or order of George Wythe."Upon these counts the prisoner was found guilty by the jury; whereupon he moved to arrest the judgment, because the offence is not within the statute under which the indictment was laid, 'inasmuch as the statute which was passed on the 18th of November, 1789, was intended to punish a pre-existing evil, which is represented as having become common, and which is minutely described in the preamble to the statute, to wit: the falsely and deceitfully contriving, devising and imagining privy tokens and counterfeit letters in other men's names, unto divers persons, their particular friends and acquaintances, whereas banks were not introduced into this Commonwealth until many years after the said 18th November, 1789, and therefore could not have been within the contemplation, any more than within the language, of the statute.

"'The phraseology of the statute precludes the possibility of its application to banks: the terms "divers persons, their particular friends and acquaintances," can relate only to private individuals, not to a body corporate or ideal body. The Bank of Virginia is no more a person than the Commonwealth of Virginia, much less is it the particular friend and acquaintance of anyone.

"'The statute requires that the person who shall be punished under it shall have gotten into his possession the money or goods of another; whereas the defendant is charged with having gotten possession of a note of the Bank of Virginia, which is neither the money or goods of the said G. W., because, having been delivered under

Page 433

a check not drawn by him, the bank hath no right to charge it to his account; neither is it the money or goods of the bank, but simply the promissory note of the bank for the future payment of money; and as to all legal purposes merely on a footing with the promissory note of an individual.'"The question arising from these reasons in arrest was adjourned to the general court.

"November 17, 1806.—The Court, consisting of Judges Tyler, White, Carrington, Stuart, Brooke, and Holmes, decided, that 'judgment on the verdict in the record mentioned ought to be arrested.'

"There was another indictment against the defendant, founded on the said act of Assembly, for fraudulently obtaining from the bank, on the 11th of April, 1806, by means of a counterfeit letter, or privy token, the sum of fifty dollars. The indictment consisted of two counts, and was exactly like the indictment in the first case above mentioned, except that in this case the defendant was charged with having obtained, by the means before mentioned, 'fifty dollars in money current in the said Commonwealth of Virginia.'

"The defendant was found guilty on this indictment also, and the same reasons were assigned in arrest of judgment as in the other case. It was also adjourned.

"The general court, composed of the same judges as in the last case, and on the same day, decided, 'That the errors aforesaid are not good and sufficient in law, and that judgment on the verdict in the record in the said ease mentioned ought to be rendered by the district court.'"

What the district court's action upon this ruling was, we have not been able to discover; but we are confident that no punishment was ever inflicted on the prisoner.[10]

The technicalities and defects of the law are so powerful in some cases as to defeat the ends of justice.

See also

- Death of George Wythe

- Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder

- The Murder of George Wythe

- Parson Blair's Snack

References

- ↑ George Wythe Munford, "Biographical Sketch of the Author", in The Two Parsons; Cupid's Sports; The Dream; and The Jewels of Virginia, (Richmond, Virginia: J.D.K. Sleight, 1884), 11-22; James Lyons Taliaferro, "George Wythe Munford," Virginia Law Register 8, no. 11 (March 1903), 783-786.

- ↑ The two parsons of Munford's tales are the Reverends John Buchanan (1743–1822) and James D. Blair (1759–1823), respectively.

- ↑ Munford, The Two Parsons, 414-433.

- ↑ Richmond Enquirer, September 9, 1806. "The pen yet lingers to add, that some of the strongest testimony exhibited before before called court and before the grand jury, was kept back from the pettit jury. The reason is, that it was gleaned from the evidence of negroes, which is not permitted by our laws to go against a white man."

- ↑ William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series 12, no. 4 (October 1955), 540-541.

- ↑ Munford, "Parson Blair's Snack.—Chancellor Wythe", The Two Parsons, 357-365. An anecdote regarding Wythe's receipt of a gift of iced crabs from Congressman Burwell Bassett, and sharing two of those crabs with James D. Blair, who must attempt to split them among himself, John Buchanan, George Wythe Munford, and William Radford.

- ↑ 'While resident in Richmond, Mr. Wythe took up the study of Hebrew, pursuing it closely with grammar and dictionary, and once a week a Jewish Rabbi by the name of Seixas attended him, to see how he progressed and to give him advice.' Lyon Gardiner Tyler, "George Wythe," in Vol. 1 of Great American Lawyers, edited by William Draper Lewis (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: John C. Winston, 1907), 72.

- ↑ Ann Lewis (1726–1748), in actuality Ann (or Anne) was the daughter of Zachary Lewis, sister of John Lewis, Spotsylvania Co., Virginia.

- ↑ See Jefferson's Notes for the Biography of George Wythe, p. 3.

- ↑ 'He was convicted and condemned to six months' imprisonment in jail, and to one hour's exposure on the pillory, at the market-house in the city of Richmond. But this sentence was never executed. The General Court had arrested one judgment; but the appeal to them on another indictment was ineffectual; yet the Court below granted him a new trial, and then the prosecuting attorney entered a nolle prosequi. The unfortunate man then sought refuge in the West; where his career was brought to a premature and miserable close.' B.B. Minor, "Memoir of the Author" in George Wythe, Decisions of Cases In Virginia, By the High Court Chancery, with Remarks Upon Decrees By the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions (Richmond, Virginia: J.W. Randolph, 1852), xxviii.

External links

Read this book in Google Books.