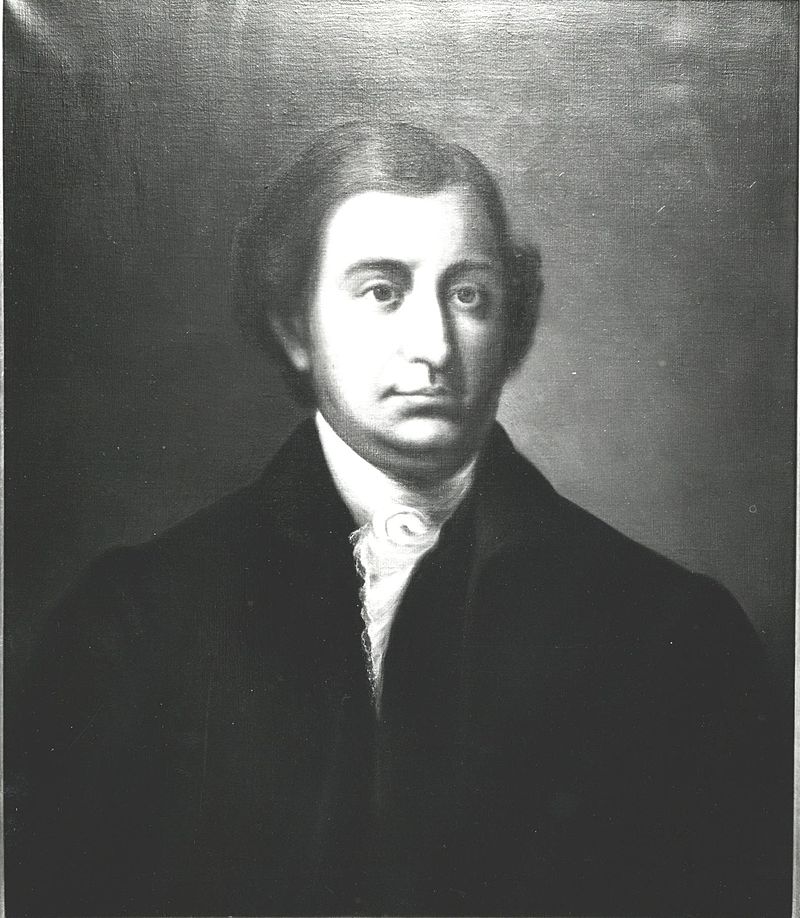

Edmund Randolph

| Edmund Randolph | |

| United States Secretary of State | |

| In office | |

| 1794-95 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| United States Attorney General (1st) | |

| In office | |

| 1789-1794 | |

| Delegate to the Virginia Ratification Convention | |

| In office | |

| 1788 | |

| Delegate to the Constitutional Convention | |

| In office | |

| 1787 | |

| Governor of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| 1786-1788 | |

| Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| 1776-1786 | |

| Mayor of Williamsburg | |

| In office | |

| 1776-1777 | |

| Delegate for Williamsburg to the Fifth Virginia Convention | |

| In office | |

| 1776 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 10, 1753 |

| Tazewell Hall, Williamsburg, Virginia | |

| Died | September 12, 1813 |

| Carter Hall, Millwood, Virginia | |

| Resting place | Old Chapel Cemetery, Millwood, Virginia |

| Alma mater | The College of William & Mary |

| Profession | Soldier, lawyer, and politician |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Nicholas (daughter to Robert Carter Nicholas, Virginia's first state treasurer) |

| Known for | First U.S. Attorney General |

Edmund Randolph was born in Williamsburg, Virginia, to John Randolph and Ariana Jennings. His father, John Randolph, as well as his grandfather, Sir John Randolph, served as king's attorney in colonial Virginia. Consequently, young Randolph grew up in a home that "cherished the law as a profession."[1]

Randolph attended the College of William & Mary where he may have studied law with George Wythe. Sources are conflicted over whether Randolph studied law with Wythe or at his father's law practice post-graduation.[2] The traditional view has been that Randolph studied with his father, however, the most recent "Colonial Williamsburg pronouncement" states that where Randolph studied law is unknown.[3] Regardless of where he received his legal education, Randolph began practicing law at the age of twenty-one.[4]

Due to the impending revolutionary crisis, Randolph's loyalist followed Lord Dunmore home to England. However, Randolph remained committed to the patriot cause. In 1775, he joined the Continental army and even served as aide-de-camp for George Washington.[5] However, Randolph's uncle, Peyton Randolph, died later that year and Randolph was forced to leave military service and settle his uncle's affairs.[6]

In 1776 Randolph married Elizabeth Nicholas, with whom he had six children.[7] That same year, he took George Wythe's place at the Virginia Convention as Williamsburg's delegate since Wythe was busy serving in Congress. The youngest delegate to the Convention, Randolph was part of the "prestigious committee" that drafted both the Virginia Declaration of Rights and the Virginia Constitution. Soon afterwards, Virginia's delegates selected him as the commonwealth's first attorney general.[8] In 1776, Randolph also became the mayor of Williamsburg.[9] In 1779 Randolph was elected to the Continental Congress. However, he only served for one year due to his legal and mayoral responsibilities back in Williamsburg. Randolph was able to briefly return to the Congress in 1781 where he became "lifelong" friends with James Madison.[10]

On November 7, 1786, Randolph was elected governor of Virginia. While he was the seventh governor of Virginia, Randolph was the first governor elected under U.S. statehood. As governor, he was "the natural choice to head Virginia's delegation" to the federal convention in Philadelphia.[11]

Randolph introduced the Virginia Plan to the convention and sat on the Committee of Detail, which was tasked with preparing a draft of the Constitution. However, Randolph declined to sign the Constitution after its adoption. He felt it had evolved to the point where it was "not sufficiently republican." Randolph preferred a three-man council rather than a one-man executive, which he feared was "the foetus of monarchy." However, Randolph did work to gain Virginia's support for the Constitution since he believed it was the only way to actually achieve the new national union.[12] As Shepard states, "His strong sense of nationalism overcame his fears of the new plan of government, and he joined James Madison, John Marshall, and Edmund Pendleton as an eloquent and passionate advocate of the federal Constitution in Virginia's convention."[13]

In 1788, Randolph resigned as governor and returned to the general assembly. In 1789 President Washington offered him the post of the federal government's first attorney general. Randolph became one of Washington's most trusted advisors, and spoke out strongly for neutrality during the war between England and France. In 1793, Randolph took Thomas Jefferson's place as Secretary of State.[14]

However, in 1794/5 Washington and Randolph had a falling out over communications between Randolph and Joseph Fauchet, the new French minister to America, and Randolph resigned from office. In response, Randolph published "A Vindication of Mr. Randolph's Resignation," which presented statements from Fauchet absolving him from all wrongdoing. But this angry attack left the president "no room to maneuver" and consequently ended their personal relationship. In 1796, Randolph published another pamphlet, "Political Truth," meant to set forth the disputed events in a calmer tone and support the Republicans attempting to shut down the Jay Treaty.[15]

After resigning, Randolph moved to Richmond and set up his law practice. In 1807 he helped represent Aaron Burr during his trial before Richmond's U.S. Circuit Court. Randolph struggled with significant financial problems until his death, including issues over "lost or unaccounted for" State Department funds for which he was legally responsible as former Secretary. He also suffered from increasing paralysis in his old age. Randolph died at Carter Hall on September 12, 1813, and is buried in the Old Chapel Cemetery in Millwood, Virginia.[16]

See also

- Randolph's History of Virginia

- Wythe the Teacher

- Wythe to Edmund Randolph, 16 June 1787

- Wythe to Thomas Jefferson and Edmund Randolph, 17 August 1793

References

- ↑ American National Biography Online, s.v. "Randolph, Edmund," by E. Lee Shepard, accessed February 2, 2016.

- ↑ John R. Vile, Great American Lawyers: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1 (ABC-CLIO, 2001), 577, accessed online February 4, 2016. See also Thomas Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe" (1998).

- ↑ Steve Sheppard, The History of Legal Education in the United States: Commentaries and Primary Sources, Volume 1 (The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 1999), 143, accessed online February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Vile, Great American Lawyers, 577.

- ↑ "Edmund Randolph" FindLaw, accessed February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Shepard, "Randolph, Edmund."

- ↑ Edmund Randolph" Findlaw.

- ↑ Shepard, "Randolph, Edmund."

- ↑ "Edmund Randolph" FindLaw.

- ↑ Shepard, "Randolph, Edmund."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Edmund Randolph" FindLaw.

- ↑ Shepard, "Randolph, Edmund."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

Further Reading

- Kevin R. C. Gutzman, "Edmund Randolph and Virginia Constitutionalism," The Review of Politics, Vol. 66, No. 3 (Summer, 2004), pp. 469-497.