"Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder: A Documentary Essay"

Wythe scholar W. Edwin Hemphill contributed to a special issue of The William and Mary Quarterly, dedicated to the murder of George Wythe, in October, 1955. The issue was published in accordance with the Marshall-Wythe celebration at the College of William & Mary Law School on September 25, 1954, for the bicentennial of John Marshall's birth. The journal pairs Hemphill's essay on "Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder,"[1] with another by Julian P. Boyd, "Murder of George Wythe."[2] Hemphill had rediscovered witness testimony given for Sweeney's murder trial in 1806, and both authors made use of this new information.

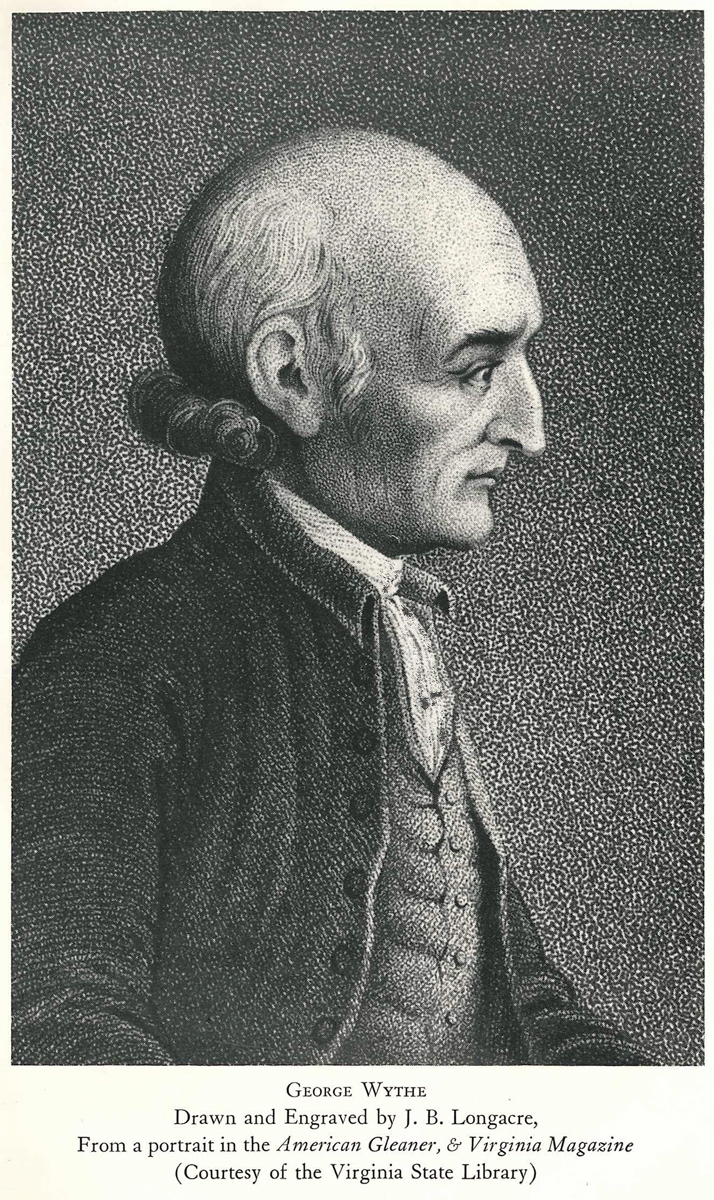

Hemphill and Boyd's work was published as a pamphlet reprint the same year, under the title: The Murder of George Wythe: Two Essays (Williamsburg, VA: Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1955).

Contents

- 1 Article text, October 1955

- 1.1 Page 543

- 1.2 Page 544

- 1.3 Page 545

- 1.4 Page 546

- 1.5 Page 547

- 1.6 Page 548

- 1.7 Page 549

- 1.8 Page 550

- 1.9 Page 551

- 1.10 Page 552

- 1.11 Page 553

- 1.12 Page 554

- 1.13 Page 555

- 1.14 Page 556

- 1.15 Page 557

- 1.16 Page 558

- 1.17 Page 559

- 1.18 Page 560

- 1.19 Page 561

- 1.20 Page 562

- 1.21 Page 563

- 1.22 Page 564

- 1.23 Page 565

- 1.24 Page 566

- 1.25 Page 567

- 1.26 Page 568

- 1.27 Page 569

- 1.28 Page 570

- 1.29 Page 571

- 1.30 Page 572

- 1.31 Page 573

- 1.32 Page 574

- 2 See also

- 3 References

- 4 External links

Article text, October 1955

Page 543

Examinations of George Wythe Swinney

for Forgery and Murder: A Documentary Essay

W. Edwin Hemphill*“I SHUDDER when I think of it." Thus wrote John Page three weeks after the death of George Wythe in Richmond on June 8, 1806.1 Less than a year and a half had elapsed since a "numerous concourse" of Jeffersonian Republicans had gathered at the Washington Tavern in the capital on March 4, 1805, to celebrate the second inauguration of Thomas Jefferson as the President of the United States. On the joyous occasion of the party's victory banquet Governor Page had asked Judge Wythe to retire and had then proposed a volunteer toast to "George Wythe, distinguished alike for his wisdom and integrity as a magistrate, and his zeal and disinterestedness as a patriot." The tavern's hall had resounded with nine cheers—as many as were given in response to any prearranged or spontaneous toast, even that to the President himself.2 Nine months later Page had retired from the governorship.

As he sat at his writing desk late in June, 1806, amid the peace and security of "Rosewell," his magnificent home in Gloucester County, John Page reflected upon the saddening, disheartening news he had heard during a recent trip to Richmond. William DuVal, George Wythe's nearest neighbor, had told Page how their mutual friend had suffered and had died—and how very suspect certain circumstances preceding that death seemed. But nothing had yet been proved. So the circumspect Page scribbled to another friend an outburst that was more a sermon than a digest of the evidence. "I know only enough" about the "horrid tale," he remarked in his letter to St. George Tucker, one of Wythe's students and the judge who had succeeded Wythe in the chair of law in the College

* Mr. Hemphill is Managing Editor of Virginia Cavalcade and a member of the staff of the Virginia State Library. These depositions were discovered by Mr. Hemphill and are now printed for the first time in this issue of the Quarterly.

1 John Page to St. George Tucker, Jun. 29, 1806, Tucker-Coleman Papers, Colonial Williamsburg.

2 Richmond Enquirer, Mar. 8, 1805.

Page 544

of William and Mary, "to shock my Soul." But the former Governor could not forbear comment along other lines. The murder of Chancellor Wythe, he exclaimed, made him "feel for humanity—and the wounded honor of my Country!"3

Governor William H. Cabell, Page's successor, was also distressed. He reminded one of his sisters-in-law of their experience when they had visited a Miss Nelson, who had then been living in the modest Richmond home of her uncle, the widowered, scholarly Chancellor. "She and all of us were almost children, and few grown men would have found any interest in staying in the room where we were. But the good old gentleman brought forth his philosophical apparatus and amused us by exhibiting experiments, which we did not well comprehend, it is true, but he tried to make us do so, and we felt elevated by such attentions from so great a man."4 [3]

The up-and-coming William Wirt, who had served for a year in a judicial office coordinate with that of the victim,5 wrote from Norfolk to James Monroe, who was abroad, in indignant terms about the "dose of arsenick administered" to "poor old Chancellor Wythe."6 Five weeks later Wirt could assure his absent wife, "I dare say you have heard me say that I hoped no one would undertake the defence of [the accused, George Wythe] Swinney, but that he would be left to the fate which he seemed so justly to merit."7

The editor of a Richmond newspaper was upset enough to describe his news announcement of the death as a "painful task."8 An editor in Raleigh, North Carolina, was told "by a gentleman lately from Rich-

3 John Page to St. George Tucker, Jun. 29, 1806, Tucker-Coleman Papers.

4 William H. Cabell to Mrs. William Wirt (undated), quoted in John Pendleton Kennedy, Memoirs of the Life of William Wirt, Attorney General of the United States (Philadelphia, 1849), I, 151-152. Hereafter cited as Kennedy, William Wirt. [Ed. note: This letter was more likely written by Judge Cabell's wife, Agnes, to her sister, Mrs. Elizabeth Gable Wirt.]

5 Ambitious for wealth, Wirt found his position as judge of the Superior Court of Chancery for the Eastern District irksome, its salary barely adequate in view of his second marriage, which took place in September, 1802. It "is possible," he observed wryly, "that I may, like Mr. Wythe, grow old in judicial honors and Roman poverty. I may die beloved, reverenced almost to canonization by my country, and my wife and children, as they beg for bread, may have to boast that they were mine." William Wirt to Dabney Carr, Feb. 13, 1803, ibid., 95. In May, 1803, Wirt returned to the practice of law as an attorney, with his residence and headquarters in Norfolk. Ibid., 87-101.

6 William Wirt to James Monroe, Jun. 10, 1806, Monroe Papers, vol. XI, no. 1373, Library of Congress.

7 William Wirt to Elizabeth Gamble Wirt, Jul. 13, 1806, Kennedy, William Wirt, 1, 152-153.

Page 545

mond" about the crime and was thus enabled to "scoop" the world by publishing the first printed details, albeit inaccurate ones, of the "circumstances of this horrid transaction."9 Newspapers as far away as Boston recorded its effect.10 Richmond's press devoted an apparently unprecedented amount of space to the modest, touching, but reserved funeral oration by William Munford11 and to laudatory tributes received as anonymous communications to the editors; the total aggregated what seems to have been more column inches of eulogy than had been elicited in Virginia newspapers by the death of George Washington or by that of any other person.12

Washington's imaginative, opportunistic biographer, Mason Locke Weems, seized upon news that had "quite galvanized" the "very young and tender hearted" in Charleston, South Carolina, as excuse enough for a discursive essay. That itinerant book-peddler described himself as "getting now to be a little oldish . . . , and daily, as becomes a stranger in Charleston, at this season, looking out for a squall of the same sort." Weems viewed with equanimity the fact that "death, by a touch of his old thresher, with equal ease, brings down a Chancellor or a cherry." He professed no grief over the death of the Virginian he portrayed as "The Honest Lawyer." On the contrary, the effusive "Parson" enjoined joy "that this veteran of the law, after a life of glorious toil, to revive the golden age of justice on earth, was returned to the high courts of heaven-not

9 Raleigh, N. C., Minerva, Jun. 16, 1806.

10 Boston, Mass., Gazette, Jun. 19, 1806, and Columbian Centinel, Jun. 21, 1806.

11 After the death of Wythe's second wife in 1787, William Munford (1775-1825) had lived in Wythe's home in Williamsburg and had been a special object of Wythe's generous attentions to youth. Grateful, Munford named his oldest child George Wythe Munford "after my old friend and benefactor the Chancellor." William Munford to his sister-in-law, Mrs. Mary R. Preston, Jan. 10, 1803, Munford- Ellis Papers, Duke University Library. Munford, his heart "torn with sorrow," then accepted the Council of State's assignment to preach the funeral oration, partly because "the ties of gratitude to that best of men, for the extraordinary kindness he ever manifested towards me, ought to prohibit my suffering him to go to his grave without an Eulogy." William Munford to Governor William H. Cabell, Jun. 8, 1806, Executive Papers, Virginia State Library. The funeral oration by Munford was printed in its entirety by two Richmond newspapers: Richmond Enquirer, Jun. 13 and 17, 1806; Richmond Virginia Argus, Jun. 17, 1806.

12 See issues of the Enquirer, the Impartial Observer, the Virginia Argus, and the Virginia Gazette, & General Advertiser during the first three or four weeks after Jun. 8, 1806. The author's comparison is based upon impressions rather than upon actual counts of the space allotted by Richmond editors to obituaries, eulogies, etc., for Wythe and for such other distinguished citizens as George Washington, who had died in 1799, and Edmund Pendleton, who had died in 1803.

Page 546

pale and trembling . . . , wet with widows' tears, and blood of murdered patriots, to meet the tear-avenging God; but bright in conscious integrity, with hands pure as the sweet palms which press the alabaster bottles of life, and in robes of innocence, snow-white as those that angels wear, to meet the smiles of the Judge Supreme, and the acclamations of brother saints innumerable."'13

Celebrants of the Fourth of July in 1806 drank toasts to the memory of George Wythe.14 Restricted to severe brevity by that social form of tribute, those who gathered for the Fourth at Lexington, Kentucky, remembered Wythe simply as "a faithful labourer in the vineyard of the republic."15 There the orator of the day was Henry Clay, who until his own death remained proud of the fact that he had been associated with Wythe's court during the 1790's. Indeed, young Clay had been the amanuensis who transcribed for publication the Chancellor's annotated decisions, confusingly peppered though they were with Greek phrases Clay had been able neither to understand nor to write well.16 Saddened by the news that had plunged Richmond into mourning (news that had just reached Lexington), Clay made his address "short and impressive."17

The sense of revulsion felt throughout the country crossed party lines as well as state lines. A Federalist organ in the nation's largest city copied from the Richmond Enquirer two paragraphs of Republican editor Thomas Ritchie's shocked obituary. To those paragraphs it appended the Petersburg, Virginia, Republican's pointed comment: "It is generally believed, that this patriot, has been brought to the grave, by means, the 'most foul, base and unnatural,' and that the accused is to undergo an examination."18 Even a modern interpreter of the Old Dominion cites the felony as the worst example of the cussedness—or something worse—

13 M. L. Weems, "The Honest Lawyer: An Anecdote," Charleston, S. C., Times, Jul. 1, 1806.

14 Richmond Enquirer, Jul. 8, 1806.

15 Lexington Kentucky Gazette, Jul. 5, 1806.

16 Henry Clay to B. B. Minor, May 3, 1851, printed in Benjamin Blake Minor, 'Memoir of the Author," in George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia, by the High Court of Chancery, with Remarks upon Decrees, by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions (2d ed., B. B. Minor, ed., xxxii-xxxvi. Richmond, 1852), Hereafter cited as Wythe, Decisions.

17 Bernard Mayo, Henry Clay, Spokesman of the New West (Boston, 1937), 208-209.

18 Philadelphia, Pa., Poulson's American Daily Advertiser, Jun. 17, 1806. This newspaper attributed the remark to the Petersburg Republican of an unspecified date.

Page 547

that she attributes to Virginians.19 The murder of George Wythe took at the time top or high rank among the state's most heinous crimes. It still does.

Inevitably, the revolting affair created quite a stir, for people will talk. Throughout the week before the prostrated Wythe's last breath set the bells of Richmond a-tolling, his death was a foregone conclusion. People marveled that a man of his age could so long survive the excruciating agonies of so insidious and lethal a poison. While Wythe still suffered, strong suspicion was aroused. Circumstances and tangible evidence converted suspicion into conviction at least seven days before the poison produced its ultimate effect upon the Chancellor's strong constitution.

The suspect was as undoubted as was the conclusion that Wythe was a victim of premeditated murder by means of arsenic. Invariably the slayer was identified as the venerable patriot's teen-aged grandnephew and namesake, George Wythe Swinney, an ingrate who had already proved himself unworthy of the home and education he had enjoyed for several years under the hip roof of the Chancellor's unpretentious cottage. Had not that young reprobate stolen books and money from his too-trusting benefactor? Had he not forged checks against his patron's bank account? And had it not been generally known, doubtless by Swinney himself, that he was the chief heir to Wythe's estate, a modest one but doubtless large enough to provide some relief to a culprit in financial difficulties? So, people said, he had placed his fatal dose in the breakfast coffee served in the unsuspecting household on Sunday morning, May 25. Immediately after that meal the good old judge and two freed Negroes had become critically ill. Lydia Broadnax, the Chancellor's faithful cook and servant, recovered. Michael Brown, the mulatto lad to whom Wythe had personally been giving a classical education—Greek and all—as a practical experiment in testing and developing the intelligence of Virginia's other race, had died on the next Sunday, June 1. The Chancellor himself lived in torment—and perhaps toward the end in a merciful coma—through a second week, but he died on the second Sunday morning, June 8. Fortunately, however, he did not expire before he had altered his will to disinherit the villainous Swinney.

Such is the traditional account of the death of Wythe—a paraphrase expanded to greater length than any known to have been written within the next two weeks, doubtless shorter than many conversational versions

19 Virginia Moore, Virginia Is a State of Mind (New York, 1943), 190-191.

Page 548

of the time, and certainly embodying the contemporary explanations of the timing, the method, and the motive of the murderer of Michael Brown and George Wythe.20 This story of the baneful circumstances has persisted ever since 1806. In its retellings it has undergone normal embellishments and amendments. Developments not fully understood when they occurred gave the tale a poor foundation at the start. The recollections of its original narrators grew more and more subject to error with the passing years. Family traditions, transmitted orally, added details and supplied conversations that seem more logical than they are trustworthy. Fanciful emphases and interpretations have been born of assumptions, not of research.

The only substantial modification, however, has been a pronounced tendency to portray the poisoning of Wythe as an accident, while that of Michael Brown has remained the result of intentional murder. This alteration cannot be traced backward beyond 1850. It stems from two sources that were not independent of each other. One was the quite faulty memory of Dr. John Dove of Richmond, who claimed in 1856 that he had been "present during the sickness & death of Judge Wythe." Dove alleged that the Chancellor had been ill before May 25, 1806, and that Swinney had not expected him to eat breakfast that Sunday morning where the poisoned coffee was to be served. The other source was Benjamin Blake Minor, editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, who contributed a biographical sketch to the second edition of the Chancellor's Decisions (1852). Minor talked with Dr. Dove, who undoubtedly told him something to the effect that Swinney had "vowed vengeance" only against the mulatto boy; and

20 Evidently the earliest summaries of the circumstances now extant are in the reliable letters written by William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson on Jun. 4 and 8, preserved in the Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Neither attributes to the poisonings a plain method or motive. The earliest written statement as to motivation and method is apparently to be found in the letter of Jun. 10, 1806, from William Wirt in Norfolk to James Monroe, Monroe Papers, vol. XI, no. 1373. That letter was written before Wirt had learned of Wythe's death. Internal evidence in Wirt's letter indicates that the allegations it relayed were based exclusively on information written on Jun. 5, in a letter that has not been found, by Governor William H. Cabell, his brother-in-law. A later account is in the brief, less specific recollection recorded by Littleton Waller Tazewell, who wrote that "it was generally believed" that Wythe's death "was produced by poison, administered in his coffee, by a reprobate boy, a relation of his who he had undertaken to educate, and who was afterwards convicted of having committed many forgeries of checks in his patrons name." "Sketches of his own family, written by Littleton Waller Tazewell, for the use of his children. Norfolk. Virginia. 1823" (MS. in the Virginia State Library), 121.

Page 549

Minor found what seemed to him to be sufficient substantiation in Wythe's will and two of its codicils, which made Swinney the residuary legatee of bequests to Michael Brown.21 Until now the only serious analysis of the traditional account of Wythe's death and of the Dove-Minor misinterpretation has been that of Julian P. Boyd. His lucidly reasoned booklet on The Murder of George Wythe assayed them chiefly by the test of comparison with information found in seven previously unexploited letters written in 1806 to President Jefferson by Wythe's intimate friend and executor, William DuVal.22

But other and even better contemporary records are also extant, and it is good that the William and Mary Quarterly affords space in this issue both for them and Dr. Boyd's thoughtful interpretation, now relatively unavailable. Chief among these additional documents are official court records of the preliminary trials of George Wythe Swinney for forgery and murder. Like pirates' gold buried in a forgotten pit, they lay neglected through more than a century and a quarter despite recurrent curiosity about Wythe's tragic death. These legal records, discovered by the present writer a number of years ago and now published for the first time, contain precious nuggets of authentic information. They include digests of the sworn testimony of sixteen witnesses for the prosecution against Swinney. They add up to a convincing indictment of him. The discovery was made in the office of the Clerk of the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond,23 where the documents lay within the

21 Both of the phrases quoted above are from Dr. Dove's recorded recollections, which are replete with provable errors and must be considered wholly suspect. "Memoranda concerning the death of Chancellor Wythe—Signed in the Aut[o]-g[rap]h. of T[homas]. H. Wynne and rec'd by him from Dr. John Dove, Sept. 16, 1856," MS. in the Brock Collection, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery. Hereafter cited as Dove, "Memoranda." For evidence that John Dove, M.D., was a Richmond practitioner from about 1822 to about 1852, see Wyndham B. Blanton, Medicine in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century (Richmond, 1933), 48, 76, 91, 238, 240. For evidence that Dove influenced Minor directly, see Minor, "Memoir of the Author," in Wythe, Decisions, xxvii.

22 Julian P. Boyd, The Murder of George Wythe (Philadelphia, 1949).

23 Binder's title "Order Book No. 6, 1804-1806," 464-465, 482-488. Rough drafts of the records for these two cases of the Commonwealth v. Swinney—drafts identical to the final ones in every important respect—can be found in the same office in the volume given the binder's title of "Minutes No. 3, 1802-1806" (MS. with pages not numbered) under dates of Jun. 2 and 23, 1806, respectively. Microfilm copies of both the Minute Book and the Order Book are available in the Virginia State Library. The final drafts of the two documents have been transcribed from the Order Book for publication below.

Page 550

domain of the very court to which the laws of Virginia prevailing in 1806 required that such an offender in Richmond as Swinney should be brought first for any trial of which an official record would have been kept. When Richmond had been incorporated in 1782, it was made a unit of local government. The General Assembly had provided by law for the annual election of twelve citizens to serve in their spare time as municipal officials. Half of them were to constitute a legislative Common Council. The remaining six—a mayor, a recorder, and four aldermen—were commanded "to hold a court of hustings" each month. Its jurisdiction in Richmond corresponded to that of a county court within county boundaries. Each of the judges of the Hustings Court had been vested with the powers of a justice of the peace, and they had been specifically assigned the duty "of examining criminals for all offences committed within the limits of the said corporation." If they found a defendant guilty of a serious crime, they were to refer him to a higher court for trial before professional judges and a jury.24 These governmental and legal arrangements for the preservation of law and order had been modified only slightly in later statutes, but a law of 1803 had increased the membership of the Common Council to fifteen and that of the Hustings Court to nine, doubtless in recognition of Richmond's growth to a population of more than five thousand.25 We shall find that not all of our questions are answered by these documents, but no searcher for the treasure-trove could reasonably have expected it to be so rich. Yet it multiplies by many times the amount of contemporary data at our disposal. It enables us to confirm some details reported unofficially at the time and to correct others. It supplies us with vivid portraits of a gloomy, wicked, and yet remorseful youth; of the last days of a questioning, then convinced, and ultimately forgiving victim; of the anxious solicitude and growing outrage of the latter's friends; and of their transition from innocent acceptance of his serious illness as a natural thing to mounting suspicion, relatively thorough investigation, and distressing proof of the poisoner's guilt. Coupled with our greater knowledge of toxicology and with other contemporary records not utilized

24 William Waller Hening, compiler, The Statutes at Large ... of Virginia . . . (Richmond, Philadelphia, New York, 1819-1823,) XI (Richmond, 1823), 45-51. Hereafter cited as Hening, Statutes.

25 Ibid., XII (Richmond, 1823), 407-408; Samuel Shepherd, compiler, The Statutes at Large of Virginia,. . . 1792, to . . . 1806 . . . (Richmond, 1835-1836), II, 93, 422-425, III, 73-75. Hereafter cited as Shepherd, Statutes.

Page 551

by previous investigators, it affords us a surer understanding of the grim story of the unpunished forgeries and murders committed by George Wythe Swinney than was vouchsafed to any of the people who mourned the death of Chancellor Wythe and sought with decreasing fervor to do justice to the cause of it—a more reliable understanding, indeed, than any of our predecessors attained.

The official record of the examination of Swinney for alleged forgery reads as follows:

At a Court of Hustings called and held for the City of Richmond at the Courthouse, on Monday, the second day of June 1806, for the examination of George W. Swinney,26 who stands accused of forgery.27

Present

Edward Carrington, Gentleman, Mayor,

Samuel Pleasants, Gentleman, Recorder,

Henry S. Shore, William Goodwin, Anderson Barret,

David Lambert and William Richardson, Gentlemen, Aldermen.

The prisoner was led to the bar in custody of the Sergeant of this City; whereupon sundry witnesses were sworn and examined, and the prisoner in his defence fully heard: On consideration whereof, the Court is of opinion that the prisoner is guilty of the offence aforesaid, and doth order that he undergo a trial therefor at the next District Court directed by law to be holden at the Capitol in this City: and it is further ordered that the said George W. Swinney be bound in a recognizance in the penalty of one thousand dollars, with suf-

26 George Wythe Swinney, whose surname occurs in contemporary records also in the form of various spellings of Sweeney, was a grandson of George Wythe's sister and hence a grandnephew of Wythe. For genealogical information concerning him and related Sweeneys see W. Edwin Hemphill, George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Virginia, 1937), 40.

27 Swinney had doubtless been accused of forgery as the result of a preliminary hearing before one or more of the municipal magistrates or justices of the peace, presumably within the last five days of the preceding week, May 27-31, as is indicated by the testimony of the first witness below. William Wirt enumerated a few other manifestations of dishonesty on Swinney's part that had been preludes to his climactic crime: "The young villain (only about 16 or 17) had been in the habit of robbing his uncle [i.e., his granduncle, George Wythe] with a false-key, had sold three trunks of his most valuable law-books, had forged his checks on the bank to a considerable amount, & wound up his villainies by this act [of murder]." William Wirt to James Monroe, Jun. 10, 1806, Monroe Papers, vol. XI, no. 1373.

Page 552

ficient security in a like penalty, for his personal appearance before the Judges of the said district Court, on the first day of the next term thereof, to answer the Commonwealth of the offence aforesaid; and failing to give the security required, he is remanded to jail until he shall give such security, or shall be otherwise discharged by the course of law.

William Dandridge (Teller of the Bank of Virginia) a witness on the foregoing examination, being sworn, deposeth and saith: That on Tuesday last [May 27], the prisoner produced to him at the bank of Virginia, a check thereon for the sum of one hundred dollars, drawn in the name of George Wythe esquire, which the deponent paid. That some time after, on examining the check, he suspected it to be a forged one, and he thereupon went to the prisoner and stated that he believed there was a mistake in said check; That the prisoner immediately produced the money and delivered the same to the deponent. That the prisoner frequently presented checks at the bank in the name of the said George Wythe; and the deponent verily believes that six checks now produced in Court were presented by the prisoner, and are all counterfeited.

Peter Tinsley,28 another witness sworn on the said examination deposeth and saith: That he carried to George Wythe esquire seven checks drawn in his name on the bank of Virginia, who denied having drawn or signed more than one of them.

William Dandridge and Peter Tinsley here in Court acknowledge themselves indebted to his Excellency William H. Cabell governor or chief magistrate of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the sum of one hundred pounds each, of their respective goods and chattels, lands and tenements, to be levied, and to the said governor and his successors, for the use of the said Common-wealth rendered: Yet upon this Condition, that if the said William Dandridge and Peter Tinsley shall severally make their personal appearance before the Judges of the District Court directed by law to be holden at the Capitol in this City, on the first day of the next term thereof, to give evidence on behalf of the Commonwealth against George W. Swinney, who stands accused of forgery, and shall not depart thence without the leave of the said Court, then this recognizance is to be void.(Minutes signed) E: Carrington Mayor29

28 Tinsley was for many years Clerk of the High Court of Chancery.

29 One item of corrective evidence is brought out in this record. Unofficial reports of 1806, whenever they stated or implied a chronology for Swinney's crimes, invariably indicated that his forgeries and the discovery of them preceded his poisoning of Judge Wythe. On the contrary, Dandridge testified that Swinney was sus-

Page 553

The official record of the examination of Swinney on the charge of murder is a remarkably detailed one. Its unusual length doubtless reflects a common impression of the uncommon nature and circumstances of the alleged crime. The record reveals utter desperation on the part of an al-most deranged Swinney. It portrays the mounting growth of suspicion during illnesses that might have been provoked by merely natural causes. It embodies observations that link Swinney conclusively with ratsbane (white arsenic) and yellow arsenic. It records medical symptoms and measures that are not nice but seem necessary. And it indicates reserve on the part of three physicians when they gave under oath their professional judgments whether or not the death of George Wythe could be attributed to arsenic poisoning. This record is as follows:

At a Court of Hustings called and held for the City of Richmond at the Courthouse, on Monday, the 23d. day of June 1806, for the examination of George W. Swinney, who stands accused of murder.30 Present

The Same Justices as above.31

The prisoner was led to the bar in custody of the Sergeant of this City; where-upon sundry witnesses were sworn and examined, and the prisoner in his

pected for the first time of his forgeries after he had presented a sixth forged check at the bank on Tuesday, May 27. That Tuesday will be found to have been two or three days after Swinney had poisoned Wythe. On that Tuesday the Chancellor lay abed in the early stages of his mortal illness. That is one reason—and his charitable, compassionate nature may be another—for the fact that Wythe himself did not testify in court which of the seven checks "carried" to him by Tinsley he had not signed personally. Further details about the six forgeries will be revealed later in this article.

30 The accusation against Swinney for the alleged murders of "Wythe & Michael Brown the Freed Boy" had resulted, in keeping with Virginia law, from a hearing held on Jun. 18 before Mayor Edward Carrington and two other magistrates or aldermen. On that occasion the examination of witnesses "lasted near Five Hours." The mayor and his two colleagues "were of Opinion that they, Mr. Wythe & Michael, were poisoned by Geo. W Sweeney." The suspect was ordered to be held in jail to await trial by the Hustings Court as a "Court of Examination" on Jun. 23. William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, Jun. 19, 1806, Jefferson Papers. Cf. Shepherd, Statutes, III, 73-75.

31 That is to say, the same six who had been present for the trials of earlier cases on Jun. 23: Mayor Edward Carrington, Recorder Samuel Pleasants, Jr., and Aldermen Henry S. Shore, Anderson Barret, David Lambert, and William Richardson. Aldermen William DuVal, William Goodwin, and Thomas Underwood did not sit as judges for this examination. DuVal attended as a witness.

Page 554

defence fully heard: On consideration whereof, the Court is of opinion that the prisoner is guilty of the offence aforesaid, and doth order that he undergo a trial therefor before the next District Court directed by law to be holden at the Capitol in this City: and thereupon the said George W. Swinney is remanded to jail.32

Tarlton Webb,33 a witness for the Commonwealth on this examination, being sworn, deposeth and saith: That about a fortnight or three weeks before the prisoner was committed to jail, he enquired of the deponent where he could procure any ratsbane? The deponent replied that it was against the law of the United States to have it. The day before the prisoner was apprehended,34 he came to the house of the deponent's mother, and shewed the depon[en]t something wrapped in paper, which he said was Ratsbane, and informed the deponent that he intended to kill himself, and offered to give the deponent some if he wanted to die. The deponent being shown some drugs found in the jail and produced in Court by Mr. [William] Rose,35 deposes that what the prisoner showed him was like that in Mr. Rose's possession, and that there was about one table spoonful. The prisoner stated to the deponent that he was very unhappy and something pressed upon his mind; but though applied to, would not disclose the cause of his uneasiness to the deponent.

William Rose,36 another witness sworn on this examination, deposeth and

32 The Richmond Enquirer, Jun. 24, 1806, printed the following announcement of the decision: "George W. Swinney was yesterday called before the examining court of this city, on the charge of poisoning his great Uncle, the venerable George Wythe, and a servant boy. He was unanimously remanded to jail for further trial before the district court to be had in September next." Although it was not particularly customary for crime news, especially courtroom news of this tentative sort, to be widely reprinted, this item reappeared in such representative newspapers as the Richmond Virginia Argus, Jun. 25, 1806; the Alexandria Virginia Gazette, & General Advertiser, Jun. 25, 1806; the Washington, D. C., National Intelligencer, and Washington Advertiser, Jun. 30, 1806, and Universal Gazette, Jul. 3, 1806; the Augusta, Ga., Chronicle, Jul. 12, 1806; and the Savannah, Ga., Columbian Museum & Savannah Advertiser, Jul. 12, 1806, and Georgia Republican, Jul. 15, 1806.

33 This witness has not been identified positively. His testimony suggests that he was probably a youthful friend of Swinney.

34 Swinney was arrested on Wednesday, May 28, or Thursday, May 29, according to testimony given in this examination by witness William DuVal, reproduced below. Webb's testimony here to the effect that Swinney told him on May 27 or May 28 that "something pressed upon his [Swinney's] mind" can be, therefore, a veiled reference by Swinney himself to worry and remorse because of the way he had used poison, with results that had not yet proved fatal, and possibly also because of the forgery committed and detected on Tuesday, May 27.

35 For an identification of William Rose see the next paragraph and footnote 36.

36 Rose was the public jailor of Richmond. Richmond Enquirer, Jul. 8, 1817. Rose's

Page 555

saith: That his servant girl Pleasant, went into the garden about twelve o'clock the day after the prisoner was committed to jail and brought the paper this day produced [in court], the contents of which the deponent immediately knew to be arsenic. When the prisoner was committed to jail, the deponent did not search him; but about an hour and a half after, or thereabouts, hearing that it was probable he had pistols, he went into the jail and felt his pocket, and felt that there was a heavy substance wrapped in paper; but supposing that it might be coppers, or some few eighteen penny pieces, he did not take it out of his pocket. The prisoner had the use of the debtors room and the jail yard at his option. As soon [as] the arsenic was found the deponent suspected that Mr. Wythe was poisoned.

Samuel McCraw,37 another witness sworn on the said examination, deposeth and saith; That being informed by Mr. Rose, that arsenic had been found in his garden, he proposed to have the servant carried into the garden to see the place where [the arsenic had been] found, to ascertain whether it was deposited there, or thrown from the jail yard. That at the place where the servant stated the arsenic to have been found, the deponent found two papers lying about eighteen inches apart: That the crude arsenic had penetrated a little into the earth, and there were two plants one a fennel, the other a beat [sic], broken off as he supposed by the throwing the arsenic over the jail wall: The deponent thinks it must have come from the jail yard. The beat [sic] that was wounded was next [i.e., nearer] the jail wall and was wounded considerably farther from the ground than the fennel. On the first of June, one week after Mr. Wythe's attack [began], the deponent was re-quested to go to attest [the final codicil to] Mr. Wythe's will. Mr. Wythe re-quested the prisoner's room and trunk to be searched. The deponent, with others, was conducted to the room where the prisoner lodged, opened the chest and found a port folio with a quire of blotting paper, which the deponent believes to be of the same kind with what was found wrapped round the arsenic found in the garden. In the prisoner's room on a writing table, the deponent found a paper on which were a half a dozen strawberries with the appearance of arsenic having been sprinkled over them. He found a phial with an appearance of having had a liquid, some of which adhered to the side of the phial, and on examination was believed to have been a mixture of testimony and that of the next witness make it plain that the former's residence and garden adjoined the jail.

testimony and that of the next witness make it plain that the former's residence and garden adjoined the jail.

37 McCraw was one of the four witnesses who signed the final codicil to Wythe's will. Minor, "Memoir of the Author," in Wythe, Decisions, xxxviii-xxxix.

Page 556

arsenic and sulphur. He also found two pieces of coarse brown paper, with something adhering to each, which was also declared to be arsenic and sulphur. The deponent frequently visited Mr. Wythe in his last illness and he appeared to be in very great agony from the first time to his death. Some time before the death of Mr. Wythe, while this deponent was sitting by him, Mr. Wythe exclaimed, cut me—the deponent supposed he wanted to have his flannel cut loose which the deponent accordingly did, but which gave apparent displeasure to Mr. Wythe, who then putting his hand to his throat and heart again called out, cut me, but could make no further explanation: this induced a belief in the deponent and those present that it was his wish to be opened after his death. The deponent never did hear Mr. Wythe express any suspicion of having been poisoned.

Fleming Russell38 another witness sworn on the said examination deposeth and saith; That the day he received the warrant [for the arrest of Swinney] he went to Mr. Wythe's and found the prisoner: when he showed the prisoner the warrant and carried him to Major DuVal's & discovered he had no pistols, took his knife from him, and put his hand in his coat pocket, he felt very distinctly that he had two separate parcels of something wraped up in paper in his pocket but made no further search. After the prisoner was committed to jail, the deponent informed Mr. Rose, that the prisoner had some-thing else in his coat pocket and advised him to make a search, but did not go with Mr. Rose to make it.

Taylor Williams39 a witness sworn on the said examination deposeth and saith; That about three weeks before the prisoner was apprehended, he mentioned something to the deponent about poison. The deponent informed him that copperas [i.e., crystallized ferrous sulphate] and water was poison. In about six or seven days after, the prisoner began a conversation with the deponent about poison: the deponent then told him ratsbane was poison, and that a gentleman of his acquaintance used it for the purpose of killing rats, and that [it] was to be bought in the shops, but does not recollect with certainty whether the prisoner asked him where it might be had.

Major William DuVal40 another witness sworn on said examination de-

38 This witness has not been identified. Judging from his testimony, he must have been a Richmond police officer.

39 Williams appears from his testimony to have been a young friend of Swinney.

40 William DuVal was of Huguenot descent, an officer during the Revolutionary War, an attorney, a member of the Virginia General Assembly, a magistrate of Richmond who had served as mayor during 1805-1806, and an intimate friend of Wythe, whose residence was also located in the square bounded by Grace, Sixth, Franklin,

Page 557

poseth and saith; that on the 25th day of May, he went to see Mr. Wythe, without knowing he was sick, and found him very ill[,] extended on his back. Mr. Wythe said he had not caught cold, that he was as well as usual in the morning, & eat his brea[k]fast as usual; but was immediately taken extremely ill, confined on his back except when forced up, which was upwards of forty times, and had fifteen large evacuations. After the prisoner was committed for the forgery he applied to the deponent by letter to be bailed. Mr. Wythe would have nothing to do with bailing [Swinney]. Mr. Wythe said he was taken ill on the twenty fifth day of May, about nine o'clock after having eat his break-fast; that on wednesday or thursday after, the prisoner was apprehended. Mr. Wythe requested that the prisoner's room and trunk might be searched, which request he repeated frequently, and finally on the first of June prevailed on Mr. McCraw and some other gentlemen who searched the room and trunk and found some papers with something adhereing to them which was declared by Doctor Greenhow41 to be arsenic. The deponent saw the appearance of arsenic in an out house of Mr. Wythe's, in his yard, used as a shop; and [de-poseth] that some was also found in an old smoak house on a wheel barrow; which on being tried with a pin was proved to be arsenic. On thursday before Mr. Wythe's death he made an ejaculation and declared he was murdered in a low tone of voice. It was generally believed that Mr. Wythe had left the prisoner a great portion of his estate, and known that he had made some pro-vision for the mulatto boy, [Michael] Brown.

Samuel Greenhow42 another witness sworn on said examination gave the same evidence upon the search of the prisoners room and trunk with McCraw. and Fifth Streets. DuVal died in Buckingham County in 1842 at the age of 93. W. Asbury Christian, Richmond: Her Past and Present (Richmond, 1912), 57, 545; Richmond Enquirer, Jan. 13, 1842, and May 13, 1842.

41 The Greenhow to whom DuVal referred may have been the next witness, identified in footnote 42, who is known to have participated in the search of Swinney's room but is not known to have had any claim to the title of Doctor. Conceivably, on the other hand, this Doctor Greenhow may have been the Doctor James G. Greenhow who was living in Richmond in 1815. Blanton, Medicine in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century, 246, 445, citing the Richmond Virginia Argus, Mar. 1, 1815.

42 Samuel Greenhow issued, as "Principal Agent," a call for the annual meeting in 1809 of the Mutual Assurance Society, the well-known, pioneer Virginia fire insurance company. Richmond Enquirer, Dec. 24, 1808. With men like the Reverend John D. Blair, the Reverend John Buchanan, the Reverend John Holt Rice, and William Munford, Samuel Greenhow was a charter member of the Board of Managers of the Virginia Bible Society, which was organized in Jul., 1813. Christian, Richmond, 87. Greenhow was one of the four witnesses who signed the final codicil to Wythe's will. Minor, "Memoir of the Author" in Wythe, Decisions, xxxviii-xxxix.

Page 558

William Price43 another witness sworn on said examination, gave the same evidence as McCraw and Greenhow on the subject of the search of the prisoner's room, and [substantiated the testimony] of McCraw on the subject of Mr. Wythe’s request to be cut. Mr. McCraw mentioned at that time that he supposed Mr. Wythe wanted to be cut open. Mr. Wythe appeared to be in great agony during his illness, and more particularly when moved.

Nelson Abbott44 another witness sworn on said examination, deposeth and saith, that on saturday the 24th day of May last, he put an axe, now produced [in court], into a shop in Mr. Wythe’s yard, which he [Wythe] had lent him [Abbott] for a work shop; that on the 27th he went to Hanover and returned on friday the 30th when he discovered the arsenic in its present situation, and a hammer much stained with yellow, which has since been cleaned. The negroes in the shop said the prisoner had beat something they did not know what on the side of the ax with the hammer.

William Claiborne45 another witness sworn on the said examination deposeth and saith: That he went to Mr. Wythe's the wednesday after his illness [began], who informed him that the Sunday preceding in the morning, he was as well as usual, immediately after breakfast he was taken with a colarimorbus [cholera morbus] and then a violent lax, went forty times that day, and had at least fifteen large evacuations: That on Saturday night he supped [i.e., on Saturday night, May 24, Wythe had supped] on milk and strawberries. Mr. Wythe said all the negroes [of his household] were taken [sick] at the same time. The deponent went into the kitchen and found most of them very ill. He then went to Major DuVal's, and expressed his opinion that the family were poisoned; and suspected the prisoner in consequence of his having been detected [on the previous day, May 27] in the forgery, as the death of Mr. Wythe before the detection could only prevent an alteration in his will which the deponent believed was much in favor of the prisoner. The deponent frequently told the prisoner that he would be well provided for by Mr. Wythe if he behaved well. After the death of the yellow boy [Michael Brown], the deponent was told by some of the negroes that arsenic was found in the outhouses. The deponent took some off the wheelbarrow in the old smoke house, applied fire to it and found from the smell that it was arsenic. The deponent asked Mr. Wythe whether the prisoner break-

43 William Price was another of the witnesses to the final codicil to Wythe's will. Minor, "Memoir of the Author," in Wythe, Decisions, xxxviii-xxxix.

44 No information to identify this witness has been discovered.

45 William Claiborne was the father of W. C. C. Claiborne, Governor of the Territory of Orleans. Richmond Enquirer, Oct. 3, 1809.

Page 559

fasted with him the morning before he [Wythe] was taken [sick]. At first he did not answer. Afterwards he said he did not know, he [Swinney] was always called to his breakfast, but sometimes took no thing to eat or drink. Mr. Wythe observed he died in peace with all the world, and said he should leave directions for his executor to search the prisoner's trunk. This took place after the death of the boy Michael [on Sunday morning, June 46], about sunset on the first of June.

Edmund Randolph,47 being also sworn, deposeth and saith: That on Sunday the first of June about nine o'clock [A.M.], Major DuVal informed the deponent of the death of Michael from poison and [reported] Mr. Wythe as probably dying with the same. Mr. Wythe told the deponent he had supped on strawberries and milk the Saturday before he was taken ill. He wished his will to be altered so as to give to the prisoner's brothers and sisters what he had given him. The deponent made the alteration and then returned home, and afterwards went again to Mr. Wythe and informed him of the death of Michael Brown. The former codicil to the will was then destroyed and the present one made. On Wednesday the fourth of June, the deponent was in-formed by old Lydia [Broadnax] that more marks of poison had been discovered. The deponent went into the shop and saw Abbot's ax. The negro48

46 George Wythe said in the final codicil to his will, dated Jun. 1, 1806, that he had been told that Michael Brown had died that morning. Minor, "Memoir of the Author," in Wythe, Decisions, xxxviii-xxxix. An almost contemporary letter also refers to Brown's death on Sunday morning, Jun. 1. William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, Jun. 4, 1806, Jefferson Papers.

47 Edmund Randolph, the first Attorney General both of the Commonwealth of Virginia and of the United States, wrote and witnessed the final codicil to Wythe's will. See his testimony here given and Minor, "Memoir of the Author," in Wythe, Decisions, xxxviii-xxxix. Randolph's career had overlapped Wythe's through the past thirty years—for example, in the Virginia conventions of 1776 and 1788. The first of the two codicils mentioned by Randolph in his testimony evidently devised to George Wythe Swinney's brothers and sisters only what Wythe had formerly bequeathed to Swinney. The second of the two codicils mentioned by Randolph devised to George Wythe Swinney's brothers and sisters everything that Wythe had formerly bequeathed both to Swinney and to Michael Brown. The will and its codicils dated Jan. 19 and Feb. 24, 1806, were proved in the General Court of Virginia on Jun. 11, 1806, by the oaths of Edmund Randolph and Peter Tinsley; and the final codicil, dated Jun. 1, 1806, was proved by the oaths of Samuel McCraw, William Price, and Edmund Randolph. For a printed copy of the will and its three validated codicils see Minor, ibid. An attested manuscript copy is filed under Jun., 1806, in the Jefferson Papers.

48 This reference to a certain Negro is not as precise as we might wish. Doubtless, however, Randolph talked on Jun. 4 with a Negro man employed in Nelson Abbott's workshop. Possibly this man was one of the same "negroes in the shop" who, according to Abbott's deposition, had told Abbott on May 30 that they did not

Page 560

was uncertain whether [it was on] the 24th or 26th of May, that the prisoner had caused the appearances [of poisons in the workshop]; but at last settled that it was on Saturday [May 24] when he found the prisoner in the shop, and one of the doors forced, and the prisoner was in the act of pounding some-thing on the axe. The prisoner asked him what it was? the negro replied he believed it was ratsbane. The prisoner then scraped it as clean as he could off the axe and folded it up in a piece of paper, wiping the axe with shavings. It was generally understood and believed that Mr. Wythe had left the bulk of his estate to the prisoner.

Doctor James McClurg,49 another witness, being sworn, deposeth: That he was present at the opening of the body of Michael Brown. The lower part of the stomach was very much inflamed and had the appearance of the black vomit. The deponent went to visit Mr. Wythe on the day before the boy died and found him with a fever, his tongue very foul, had had no passage for twelve hours, and was free from pain. The appearance of the boy was such as arsenic might have produced; but such as might also have been produced by a great collection of bile. The deponent was also present at the opening the body of Mr. Wythe. The whole of his stomach and intestines had an uncommonly bloody appearance, that if produced by arsenic, in his [McClurg's] opinion, death would have ensued much sooner. Mr. Wythe had been frequently attacked with disordered bowells within three years last past.

Doctor James D. McCaw,50 being also sworn, deposeth: That he was called

know what substance Swinney had pounded into powder. In slight but not necessarily contradictory contrast, the Negro of whom Randolph testified simply believed on May 24 that the substance was ratsbane.

49 Under the reorganization of the College of William and Mary instigated by Thomas Jefferson in 1779, James McClurg (1746-1823), Edinburgh-trained physician, had been one of Wythe's four colleagues in the faculty. For three years Dr. McClurg held the newly created chair of the professor of anatomy and medicine. Like Wythe, McClurg went to Philadelphia in 1787 to attend the convention from which emerged the Federal Constitution. McClurg was chosen to be Richmond's mayor in 1797, 1800, and 1803. For a quarter of a century he was one of the community's out-standing physicians. When the Medical Society of Virginia was organized in 1820, he was elected its first president. Although he was too infirm to take an active part in its affairs, he was re-elected in the next year. Blanton, Medicine in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century, 13, 75-76; Christian, Richmond, 545.

50 James Drew McCaw, M.D., was one of the founders of the Medical Society of Virginia. His father, Dr. James McCaw, founded what might be called a Virginia medical dynasty destined to last five generations. Blanton, Medicine in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century, 116-117, 261, 367. James D. McCaw's offer of 1802 to inoculate the poor of Richmond against smallpox had been accepted by the Common Hall or Council. Richmond Examiner, Jun. 2, 1802. Judging by James D. McCaw's testi-

Page 561

to attend Mr Wythe on the 26th of May between four and five o'clock. He had been up with a violent puking & purging, and the deponent gave him an opiate, after which he got better, and was better until the discovery of the prisoner's forgery [on Tuesday, May 27], when he became worse and continued to grow worse. The deponent saw the boy [Michael Brown] on the day before his death, when he had a fever and complained of great pain. The deponent saw him opened after his death, and thinks that his death might have been occasioned by a great accumulation of bile.

Doctor William Foushee,51 being sworn, deposeth: That he attended the opening of Mr Wythe's body in the presence of many other physicians.52 The stomach was very much inflamed, and appeared as if a new inflamation was coming on. There was very little bile in the liver. The same appearance that his stomach and intestines exhibited might have been produced by arsenic, or any other acrid matter.

James McClurg, William Foushee, James D. McCaw, William Rose, Samuel McCraw, Fleming Russell, William Claiborne, William Price (Register) Nelson Abbott and Taylor Williams,53 here in Court acknowledge themselves

mony, he seems to have been more nearly the family physician to the Wythe household than any of the other physicians whose names occur in records concerning the Chancellor's last illness. To be compared with the recorded testimony of Dr. McClurg and that of Dr. McCaw concerning the autopsy on the body of Michael Brown is DuVal's letter to Jefferson: "As a Magistrate I requested four eminent Physicians to open the body of the Boy. They did so; from the inflamation on the Stomach & Bowels they said that it was the kind of Inflamation produced by Poison." William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, Jun. 4, 1806, Jefferson Papers.

51 William Foushee, M.D., had been born in the Northern Neck in 1749. Like McClurg, he studied medicine in Edinburgh. He served as Richmond's first mayor, 1782-1783, as the town's postmaster for several years, and as the president of its Common Hall or town council for several years. He also served in both the legislative and executive branches of the state government. For many years he presided over the James River Company's internal navigation improvement projects. The General Assembly named him among the charter trustees of the Richmond Academy in 1802. Twenty years later the Medical Society of Virginia elected him its second president. When he died in 1824, he was almost seventy-five years old and was said to have been Richmond's oldest inhabitant. His death evoked an unusually detailed obituary. Christian, Richmond, 57-58, 545; Blanton, Medicine in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century, 75-76; Richmond Enquirer, Aug. 24, 1824.

52 DuVal reported to Jefferson that William Foushee, James D. McCaw, James McClurg, and two other physicians performed the autopsy on Wythe's body on the day of his death. DuVal stated simply that they found "considerable inflamation in the Stomach," but he added in the same context that it was "strongly suspected" that Wythe and Michael Brown had been poisoned with yellow arsenic by George Wythe Swinney. William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, Jun. 8, 1806, Jefferson Papers.

53 It may be highly significant that four of the fourteen witnesses were not

Page 562

severally indebted to his Excellency William H. Cabell governor or chief magistrate of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the sum of one hundred pounds each, of their respective goods and chattels, lands and tenements, to be levied, and to the said governor and his successors, for the use of the said Commonwealth rendered: Yet upon this Condition, that if the said James McClurg, William Foushee, James D. McCaw, William Rose, Samuel McCraw, Fleming Russell, William Claiborne, William Price (Register) Nelson Abbott and Taylor Williams, shall severally make their personal appearance before the Judges of the District Court directed by law to be holden at the Capitol in this City on the first day of the next term of that Court, to give evidence on behalf of the Commonwealth against George W. Swinney, who stands accused of murder, and shall not depart thence without the leave of the said Court, this recognizance is to be void.

(Minutes signed) E: Carrington, Mayor

The depositions of the sixteen witnesses in the two proceedings of June 2 and 23 make Swinney's motives for murder clearer than other contemporary records. Obviously, that troubled knave had tried to solve more than one of his problems at once. By a single desperate deed he might forestall discovery of his forgeries, prevent any resultant reduction or cancellation of the legacy he would receive from Wythe, and claim his inheritance prematurely.

But the second Hustings Court record does not enable us to determine with finality precisely when and how Swinney committed his acts of murder. None of the testimony links arsenic with the coffee served in Wythe's cottage, according to the traditional story of the poisonings, at breakfast on Sunday, May 25. To contrary import are the depositions of Claiborne, McCraw, and Randolph. Their assertions under oath indicate that Swinney had mixed some arsenic with strawberries and that Wythe ate strawberries for supper on Saturday, May 24. Wythe's breakfast coffee may have become the supposed vehicle for the poison on the invalid ground of reasoning of the post hoc, propter hoc type. Actually, so far as we can tell,

placed under bond to be available to serve as witnesses in the forthcoming trial of Swinney on the charge of murder before the District Court. The four who were exempted from such an obligation were William DuVal, Samuel Greenhow, Edmund Randolph, and Tarlton Webb. While in some respects their testimony before the Hustings Court merely confirmed that of other witnesses, in these respects, and more especially in reference to other observations concerning which others did not testify, the evidence submitted by these four could not be omitted without weakening the case against Swinney.

Page 563

he may have consumed poisoned foods at both meals. A fatal dose of arsenic usually produces acute symptoms within about an hour after it enters the human stomach, and death usually follows within one to three days. Wythe's case was not a typical one in the latter respect, and we have scant cause to assume that it was a normal one in the former respect. Fatal dosages of arsenic have been known in rare instances to cause no symptom for as many as twelve hours, particularly if the poison was ad- ministered in solid rather than liquid form and if a full meal was consumed with it; and death has been known to result as much as two weeks after the appearance of symptoms, as it did in Wythe's case. An inexperienced, experimenting Swinney may have underestimated on May 24 the amount of arsenic required to accomplish his premeditated purpose. He may have awaked the next morning to find that his attempt of the previous afternoon or evening had failed. He may then have added a second and larger quantity of arsenic to the breakfast menu. Neither this nor any alternative possibility can be proved conclusively from the available evidence.

More important than questions about details of that sort is the official record's revelation of the limited, inconclusive nature of the physicians' findings in the two autopsies. They did not exhaust every means known to the medical scientists and chemists of their generation to determine whether or not the deaths of Michael Brown and George Wythe had been unnatural ones. One authoritative treatise, for example, published in 1832 but embodying comparatively little that had been learned since 1806, devoted fully a hundred pages to its discussion of arsenic poisoning, forty of them to various definitive tests by which the presence of arsenic can be determined. Its author commented on the ease with which that almost tasteless and odorless chemical element could be procured in various forms and compounds and could be administered surreptitiously. Then he added,

"It is fortunate, therefore, that there are few substances in nature, and perhaps hardly any other poison, whose presence can be detected in such minute quantities and with so great certainty."54 The inflamed tissues observed by the Richmond doctors were ambiguous. The same kind of examination today would do little more, if any, to pin down positively the cause of such deaths, for gastrointestinal inflammations of quite similar

54 Robert Christison, A Treatise on Poisons, in Relation to Medical Jurisprudence, Physiology, and the Practice of Physic (2d ed., Edinburgh, 1832), 223. This volume's treatment of arsenic poisoning covers pp. 223-324.

Page 564

appearance can result from any of several distinct causes, both natural and unnatural. The Richmond physicians' post-mortem inspections should not have ended short of a few simple laboratory procedures. Standard analyses of that kind would almost certainly have proved beyond question whether or not arsenic had ended the lives of the youthful Michael Brown and the aged George Wythe.

The above testimony in both of the suits of the Commonwealth v. Swinney confirms an undisputed conclusion reached by all who have ever studied the matter: Wythe himself became fully convinced on his death- bed that Swinney was a forger and a murderer. Yet, in fact, that young man escaped legal punishment for both offenses. His road to freedom was, however, a tortuous one. Sometime during the summer of 1806 the charges against him were referred to a grand jury. It returned true bills. Thus it became the third judicial body to render a verdict of guilt against Swinney on each accusation, for the same conclusion had already been reached on each count by one or more of Richmond's magistrates and by the Hustings Court. Specifically, the grand jury cleared the way for the trial of Swinney by the District Court on each of six distinct indictments—one for the murder of Wythe, another for that of Michael Brown, and four for forgeries of Wythe's name on as many checks.55

On September 2, 1806, the District Court proceeded to tackle what the Richmond Enquirer termed "the celebrated trial of George W. Sweeney, on the charge of administering arsenic to his great Uncle the venerable George Wythe." Judges Joseph Prentis and John Tyler, Sr., whose son of the same name was destined to become the tenth President of the United States, were the two members of Virginia's General Court assigned to preside over this session in the Richmond district.56 Presumably, the two judges' judicial robes hid the mourning bands of crape that they and other members of the General Court had resolved to wear on their left arms for three months in tribute to the jurist Virginia had lost.57 At the

55 There is no record of any decision in regard to the other two checks that William Dandridge and Peter Tinsley had testified were, in the opinions of Dandridge and Wythe, also forged.

56 Richmond Enquirer, Sept. 9, 1806.

57 Ibid., Jun. 24, 1806; Richmond Virginia Argus, Jun. 17, 1806; Richmond Impartial Observer, Jun. 21, 1806. The Governor and Council had resolved on Jun. 14, "in honour of the deceased," to wear black bands similarly for one month as an "outward Sign of respect to his memory." Journals of the Council of Virginia (MSS. in the Virginia State Library), XXVII, 448. When the Virginia General Assembly convened in Dec., 1806, its members also resolved unanimously to "wear a badge of

Page 565

prosecuting attorney's table sat Philip Norborne Nicholas,58 the popular young Attorney General of Virginia and successful leader in recent years of the Jeffersonian Republican party in the state. Nicholas had known Wythe while the Chancellor had still resided in Williamsburg. More recently they had been associated in various legal and political activities. Presumably, Nicholas had every reason to prosecute the case with all the vigor at his command.

But the shocked, incensed atmosphere of June had doubtless grown calmer by September, and impressive talents had been aligned on Swinney's side as counsel for the defense.59 One of these lawyers was the same Edmund Randolph who had written the codicil disinheriting Swinney, the same Randolph who had given damaging testimony against him in the Hustings Court. The other lawyer at Swinney's side was the same William Wirt who had expressed a hope that no attorney would be found to defend him, so that he would be left to suffer the fate he deserved.

Wirt had been contemplating at the beginning of the summer a desire to move from Norfolk to Richmond, for his wife found Norfolk's summers unbearable. He had concluded at that distance within a month after Wythe's death that Swinney could conceivably be innocent of murder. Judge William Nelson of the General Court had told him that "there was a difference of opinion" among Richmond doctors as to the cause of the Chancellor's death and that "the eminent McClurg, amongst others, had pronounced that his death was caused simply by bile and not by poison." Then a brother of Swinney's distressed mother had traveled eastward to implore Wirt to serve as an attorney for the defense.60

Although Wirt had already decided before that visit that "it would not be so horrible a thing to defend" Swinney "as, at first, I had thought it," the plea made by his uncle posed a problem of conscience and of reputation. By letter Wirt asked his wife, "What shall I do?" And then he proceeded to influence her decision. "If there is no moral or professional impropriety in it, I know that it might be done in a manner which would avert the displeasure of every one from me, and give me a splendid debut in the metropolis. Judge Nelson says I ought not to hesitate a moment

mourning" for one month. Washington, D.C., National Intelligencer, and Washington Advertiser, Dec. 15, 1806.

59 Ibid.

60 William Wirt to his wife, Jul. 13, 1806, Kennedy, William Wirt, I, 152-153.

Page 566

to do it; that no one can justly censure me for it; and, for his own part, he thinks it highly proper that the young man should be defended. Being himself a relation of Judge Wythe's, and having the most delicate sense of propriety, I am disposed to confide very much in his opinion."'

The issue was settled within ten days. Nelson reiterated his opinion as to "the perfect propriety of the step." Mrs. Wirt evidently protested that her husband need not fear that she would suffer reproach. "I shall defend young Swinney under your counsel," he wrote her. "My conscience is perfectly clear, from the accounts I hear of the conflicting evidence."62

Records of the District Court, in which Randolph and Wirt undertook to save the life of George Wythe Swinney, are not extant; apparently they did not survive the fire that accompanied the Confederate evacuation of Richmond in April, 1865. Only from other sources can we learn whether or not the defense attorneys achieved their goal. The Richmond Enquirer reported succinctly the results of what was probably a day replete with courtroom drama and legal technicalities. "After an able and eloquent discussion" by counsel for the Commonwealth and for Swinney, read that newspaper's summary, "the jury retired, and in a few minutes, brought in the verdict of not guilty. A similar indictment against him [Swinney] for the poisoning of Michael, a mulatto boy (who lived with Mr. Wythe) was quashed without a trial."63

There could have been no doubt whatsoever that Virginia's laws of 1806 defined murder by poisoning, if it were committed by a free person, to be murder of the first degree, punishable by death.64Some other ex- planation of the jury's astonishing verdict must be sought. Editor Thomas Ritchie offered his readers one hint why Randolph and Wirt had been able to win a quick decision in favor of their despised client. Some of the "strongest testimony" that had been heard by the Hustings Court and by the grand jury, Ritchie remarked, "was kept back from the petit jury" in the District Court. "The reason is, that it was gleaned from the evidence of negroes, which is not permitted by our laws to go against a white

61 Ibid. Nelson's distant kinship to Wythe was evidently through the second Mrs. Wythe, who had been a Taliaferro. See a copy of the will of Rebecca Cocke Taliaferro of "Powhatan," James City County, Nov. 12, 1810, in the possession of Colonial Williamsburg.

62 William Wirt to his wife, Jul. 23, 1806, Kennedy, William Wirt, 1, 154.

63 Richmond Enquirer, Sept. 9, 1806.

64 the enactments of 1796 and 1803, Shepherd, Statutes, II, 5-14 and 405-406, respectively.

Page 567

man."65 Actually, the reason assigned by the editor would have been more nearly true if he had phrased it more carefully. As far back as 1732 and as recently as 1801 the statutes of Virginia had stipulated that a Negro or a mulatto could be qualified as a witness only in a lawsuit brought against a Negro or a mulatto or by the commonwealth for one.66 That is why Lydia Broadnax had not told the Hustings Court in June whatever she knew about the involvement of George Wythe Swinney in the deaths of Michael Brown and George Wythe.

The legal disability of Negroes to testify against Swinney had loomed large in people's thinking about the prospective trials of that ingrate for murder ever since Michael had died. Even before William Wirt learned with certainty that Wythe had also been a victim, Wirt had realized that one law might prevent the fulfillment of justice under another. "The chain of circumstances fix the guilt of Sweney beyond reach of doubt," Wirt had then been willing to assert, "but some of those circumstances, material to his conviction in a court of law, depend, it seems, on black persons, & so he will escape for the poison[ings]. he is under prosecution for the forgery & of that must be convicted."67

One logical question is answered neither by Ritchie's explanation nor by Wirt's prophecy. Why was any of the evidence that had been admissible in the three previous proceedings—evidence that had resulted in three verdicts of guilt—not presented in the District Court? No record answers that question. Possibly the District Court refused to hear some of the testimony that had been given before the Hustings Court. Evidence given by the white witnesses in June concerning what Negroes had ob-

65 Richmond Enquirer, Sept. 9, 1806.

66 The exact words of the law of 1801 were: "Any negro or mulatto, bond or free, shall be a good witness in pleas of the commonwealth for or against negroes or mulattoes, bond or free, or in civil pleas where free negroes or mulattoes shall alone be parties." Shepherd, Statutes, II, 300. The statute of 1785 was to the same effect, although its provisions were couched in negative terms and omitted the words "bond" and "free" in each of the five instances of their use in the enactment of 1806. Hening, Statutes, XII (Richmond, 1823), 182-183. Digests of the 1732 and 1748 statutes and of related legislation can be found conveniently in June Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia: A Summary of the Legislative Acts of Virginia concerning Negroes from Earliest Times to the Present (Richmond, 1936), 154-155.

67 William Wirt to James Monroe, Jun. 10, 1806, Monroe Papers, vol. XI, no. 1373. Internal evidence in this letter indicates that for the facts he stated Wirt was indebted to a communication written on Jun. 5, 1806, by his brother-in-law, Governor Cabell, and the prophecies Wirt voiced may also have reflected the Governor's thinking as of that date.

Page 568

served and had told them may have been ruled inadmissible by Judges Prentis and Tyler because of its Negro source or its hearsay nature. On the other hand, we have no proof acceptable by the ordinary standards of historical criticism that Swinney was acquitted because of the repression of the testimony Lydia Broadnax or other Negroes might have given but for Virginia's laws. Ritchie's allegation about the withholding of testimony "gleaned from the evidence of negroes" remains unsubstantiated, and Wirt's prophecy can be considered to have been merely a recognition of the flimsiness of the circumstantial evidence others would be able to give.

The simple fact remains that no known witness was able to assert in any of the four proceedings that he had actually seen Swinney put poison into food eaten by Michael Brown or by George Wythe. Moreover, no physician is known to have been willing to swear that either of the two autopsies proved that death had been caused by a poison. In other words, the evidence against Swinney was purely circumstantial.

Thomas Ritchie himself had not been hysterical in his attitude toward Swinney during the first days of resentment following the news of the Chancellor's death. The editor had remembered, sanely and circum- spectly, that the accusations against Swinney had not then been proved and that, until and unless they were, he should be presumed innocent. "Every situation in life has its rights and its duties," Ritchie had cautioned his readers. "Let us therefore respect the rights of the accused."68 If Swinney's two lawyers took advantage in the District Court of every legal technicality to protect their client's rights, Ritchie should have been among the last to imply any criticism of them, for they had placed themselves under obligation to do so.

In any case, George Wythe was dead. Another man's life was at stake. It is the very genius of the legal system Wythe had received from his forefathers and had himself helped to develop and to refine that this second life should not be taken lightly. Since we do not know in detail what transpired in that Richmond courtroom on September 2, 1806, we are left in the position of being forced to accept at face value the jury's final decision, which was that Swinney had not been proved beyond reasonable doubt to have murdered George Wythe and that he was therefore not guilty. Similarly, we must accept the opinion of Attorney General Nicholas that it would have been useless to try to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Swinney had murdered Michael Brown.

Page 569

Nevertheless, we can record the fact that those jurymen are the only persons known to have expressed at any time in or since 1806 an opinion that Swinney was not a murderer. William Wirt had concluded that Swinney could conceivably be innocent of the charge, but Wirt left no record now extant that he actually believed Swinney to be the victim of an unjust accusation. The common impression throughout the summer of 1806 was that Swinney had committed two premeditated murders. That opinion has remained unchanged to this day.

George Wythe Swinney had escaped death by hanging. It remained to be seen whether or not he would become permanently branded a convicted forger. Within another twenty-four hours he received a tentative answer to this second question. On Thursday, September 3, 1806, he was adjudged guilty on two of the forgery indictments.69 But these verdicts were not allowed to stand unquestioned. Within ten days William Wirt pleaded successfully, "in an eloquent and ingenious speech" addressed to Judges Prentis and Tyler of the District Court, for arrest of judgment. Wirt's objections were considered acceptable by the two judges and were referred to the next session of the General Court for approval or rejection.70 Wirt had changed his mind since his assertion in June that Swinney would doubtless be convicted of the forgery charges.

Someone else had come earlier than Wirt to the conclusion that the laws of Virginia would not justify inflicting punishment on Swinney for having obtained certain things of value at the state's bank by using forged signatures. Indeed, former Governor Page had decided in June that what Swinney had done at the Bank of Virginia was a crime only against God, not against any law of the Commonwealth of Virginia. "As to this young Man's Forgeries," Page had commented in highly moralistic vein but with a practical twist, "when religion is out of the way, I can see nothing in our law, that could restrain him, or any one else from a free exercise of that lucrative Employment. But for a sense of religion, I myself could not have done a better act for the Benefit of my Wife & Children, than to have . . . died . .. consoled with the pleasing reflection that I had handsomely provided for my Family, in a way permitted, nay chalked out by our Laws." 71

70 Richmond Virginia Gazette, & General Advertiser, Sept. 13, 1806.

71 Page's letter continued: "I could, if under no religious impressions, tell my Wife & Children, that no one would think the worse of them for what I had done; and indeed that they would always be respected in proportion to their riches, and

Page 570