St. George Tucker

| St. George Tucker | |

| Judge, United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| February 4, 1819 – June 30, 1825 | |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | George Hay |

| Judge, United States District Court for the District of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| January 19, 1813 – February 4, 1819 | |

| Preceded by | John Tyler, Sr. |

| Succeeded by | John Curtis Underwood |

| Justice, Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals | |

| In office | |

| January 6, 1804 – March, 1811 | |

| Professor of Law and Police, College of William & Mary | |

| In office | |

| March 8, 1790 – 1804 | |

| Preceded by | George Wythe |

| Succeeded by | William Nelson |

| Judge, General Court of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| 1788 – 1803 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 10, 1752 |

| Bermuda | |

| Died | November 10, 1827 (aged 75) |

| Washington, D.C. | |

| Education | Legal apprentice for George Wythe |

| Profession | Lawyer Professor of Law and Police (1790-1804) Judge |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Bland Randolph (1778-1788) Leila Skipwith Carter (1791-1827) |

| Known for | Tucker's Blackstone |

Born on June 29, 1752 near Port Royal, Bermuda, St. George Tucker grew up in one of Bermuda's most prominent families, the Port Royal Tuckers.[1] Colonel Tucker, St. George's father, originally planned to send St. George to the Inns of Court in London to complete his education, but the Colonel's financial situation made that unlikely. After hearing that the College of William & Mary offered an inexpensive quality education, Colonel Tucker sent St. George to Virginia, where he arrived in January 1772. The Colonel soon learned that the College was more expensive than he'd been led to believe, and by 1773 St. George had left his general study course at the College to study under George Wythe.[2]

After his studies with Wythe, St. George was offered the position of deputy clerk at the Gloucester County Court, but he declined the offer in favor of a better-paying clerkship with Dinwiddie County.[3] Tucker was admitted to the bar in 1774, but did not begin practice until after the Revolutionary War, during which he served in the Virginia militia.[4]

After the war, Tucker began practicing in Virginia's county courts, and was eventually named a Commonwealth's Attorney. In 1785 he began arguing cases before the Court of Admiralty, and in 1786 was admitted to practice before the Virginia General Court, then the Commonwealth's highest legal tribunal.[5] When Virginia re-organized its court system in 1788, Tucker was named to serve as a judge in one of the newly-created District Courts, and he moved with his family to Williamsburg that same year.[6]

St. George's star rose quickly in the Virginia legal world. He argued as a friend of the court before the Virginia Court of Appeals in Commonwealth v. Caton,[7] one of the first cases in the United States discussing whether courts could exercise judicial review (Tucker's teacher, George Wythe was among the justices on the Court that day). A pamphlet Tucker wrote on commercial policy garnered enough attention that he was named one of Virginia's delegates to the Annapolis Convention of 1786, an early attempt to remedy the Articles of Confederation's defects.[8]

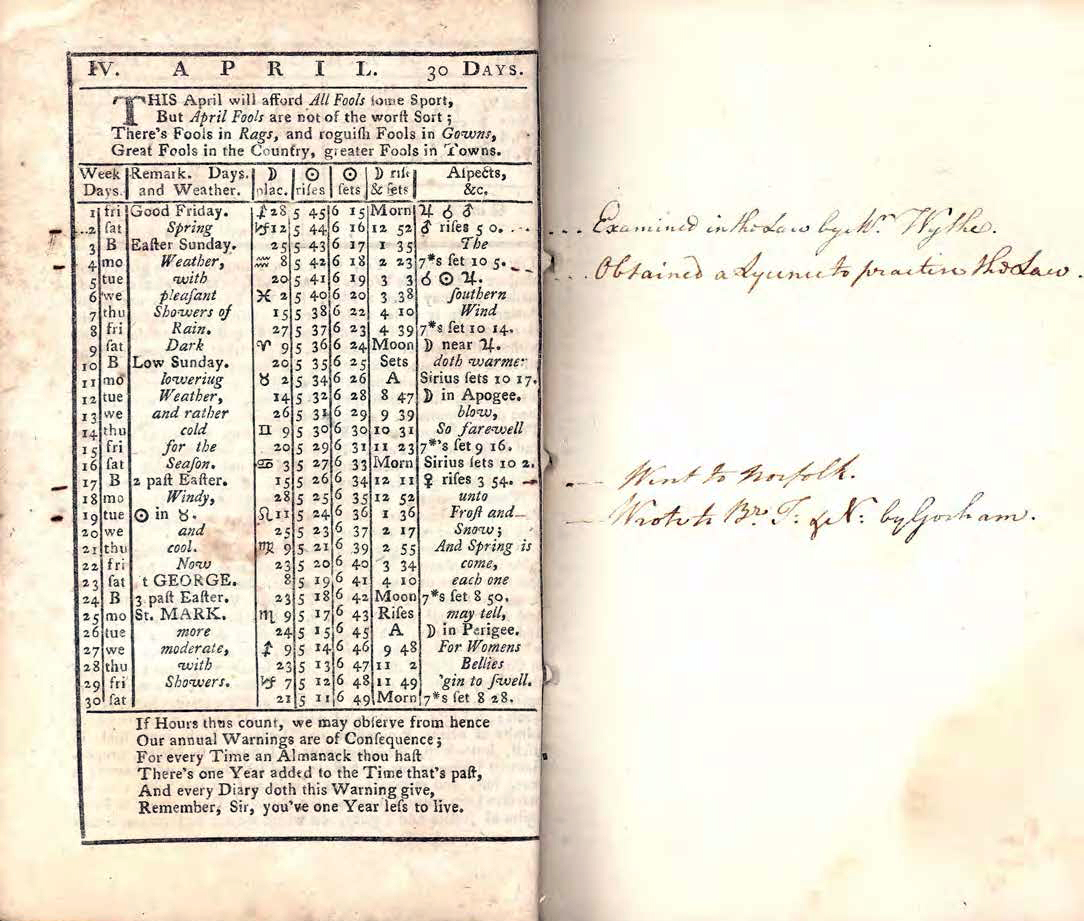

April 2, 1774: "Examined in the Law by Mr. Wythe." April 4: "Obtained a Lycence to practise the Law."

Diary notes by St. George Tucker in his copy of The Virginia Almanack for the Year of Our Lord God 1774: Being the Second after Bissextile or Leap Year (Williamsburg, VA: Printed and sold by Purdie & Dixon). Original in the St. George Tucker Signature Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.<p>

Tucker served on William & Mary's Board of Visitors for several years, and made strong efforts to protect Thomas Jefferson's revisions to the College's curriculum from conservative clergy who served on the board. When George Wythe resigned his post in 1789, Tucker was William & Mary's rector, and the Board of Visitors named him to succeed Wythe as Professor of Law and Police in 1790.[9]

Tucker used William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England as the foundation for his lectures, adding lectures on the United States Constitution, on public morality, on principles of American government, and how American law diverged from the English common law described by Blackstone.[10] The notes from these lectures later formed the basis for Tucker's edition of Blackstone's Commentaries (known as Tucker's Blackstone), one of the most highly-regarded treatises in American legal history.[11]

During Tucker's early years at the College, students would alternate readings with lectures from dawn to dusk. Many students considered Tucker's methods tough, but also noticed that they had a remarkable effect. One student, Joseph C. Cabell, wrote "[y]ou may remember that a notion formerly prevailed here that a student of law should make the study of his profession subservient to that of politics. This opinion however seems not to prevail here this course, but has yielded to one perhaps more rational."[12] Tucker's classes were in regular demand; students from other states, and even from England, came to Williamsburg to take his courses, and young men reading law under attorneys would sometimes attend a term of Tucker's courses at their supervising attorneys' behest. Under Tucker's direction in 1793, the College issued the first Bachelor of Laws granted to a student in the United States—future Governor of Virginia William H. Cabell.

After ongoing conflicts with the College over the location of classes (Tucker preferred to give lectures in his home), he resigned, effective March 1804. Soon thereafter, Tucker was named to the Virginia Court of Appeals, where he served from 1804 to 1811, and later served as a judge on the U.S. District Court for Virginia from 1813 to 1825.[13]

Throughout his legal career, Tucker published on a variety of topics, including a 1796 pamphlet urging the abolition of slavery and proposing a compromise for its gradual abolition.[14] His most influential work was Tucker's Blackstone, published in five volumes in 1803, which included his own essays and notes on the effect of the American Revolution and national and state Constitutions on the American legal system.[15] For twenty years after its publication, Tucker was the most cited American legal scholar.[16] His work is still referenced today, including by the United States Supreme Court in 2008 in United States v. Heller, which used his essays to argue that the Second Amendment was originally intended as an "individual right to bear arms." Tucker died near Warminster, Virginia, on November 10, 1827.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ Mary Haldane Coleman, St. George Tucker: Citizen of No Mean City (Richmond, Va.: Dietz Press, 1938), 1-2.

- ↑ Charles Thomas Cullen, "St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia," Ph.D. diss. (University of Virginia, 1971), 5-6, 10.

- ↑ Ibid., 16-17.

- ↑ Davison M. Douglas, "St. George Tucker (1752-1827)," Encyclopedia Virginia (Virginia Foundation for the Humanities), accessed October 11, 2013.

- ↑ Cullen, "St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia," 73.

- ↑ Charles T. Cullen, "St. George Tucker," in Legal Education in Virginia 1779-1979: A Biographical Approach, ed. W. Hamilton Bryson (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1982), 659.

- ↑ Cullen, "St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia,", 50-51.

- ↑ Ibid., 73.

- ↑ Ibid., 166-167.

- ↑ Ibid., 169.

- ↑ Davison M. Douglas, "Foreword: The Legacy of St. George Tucker," William & Mary Law Review 47, no. 4 (2006): 1112-1113.

- ↑ Ibid., 183.

- ↑ Douglas, "St. George Tucker (1752-1827)."

- ↑ E. Lee Shepard, "Tucker, St. George," American National Biography Online, accessed October 11, 2013.

- ↑ Douglas, "St. George Tucker (1752-1827)."

- ↑ David. T. Hardy, "The Lecture Notes of St. George Tucker: A Framing Era View of the Bill of Rights," Northwestern Law Review Colloquy (2008), accessed October 11, 2013.

- ↑ Shepard, "Tucker, St. George."

External links

- 1790–1804: St. George Tucker in the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository.

- St. George Tucker Law Lectures, circa 1790s, Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William & Mary

- "St. George Tucker (1752–1827)," Encyclopedia Virginia.