Commonwealth v. Caton

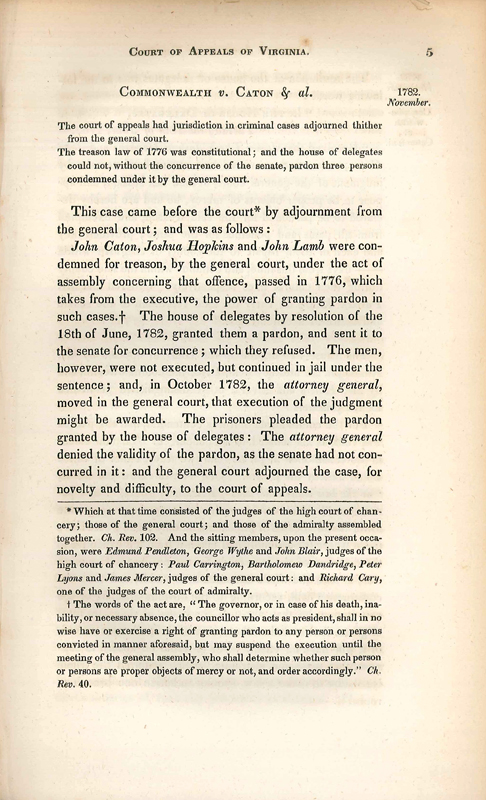

Commonwealth v. Caton, 8 Va. (4 Call) 5 (1782), is an opinion from the Virginia Court of Appeals[1] that included an early version of the doctrine of judicial review, holding that the highest court in the Commonwealth of Virginia had the power to invalidate laws that contravened the Virginia Constitution.

George Wythe was one of eight justices hearing this case brought before the Virginia Court of Appeals. At the time, the Court of Appeals included Wythe, Edmund Pendleton, and John Blair, Chancellors of the Court of Equity; Chief Judge Paul Carrington and Judges Bartholomew Dandridge, Peter Lyons, and James Mercer of the General Court; and Richard Cary, of the Court of Admiralty.[2] Wythe authored the most notable opinion in the decision, putting forth a view of judicial review that would be influential in shaping John Marshall’s enunciation of the doctrine of judicial review at the United States Supreme Court over twenty years later.

Contents

Background

At the end of the American Revolution, Virginia began to prosecute citizens who had supported the British during the War.[3] On June 15, 1782, the Virginia General Court sentenced three men, John Caton, Joshua Hopkins, and James Lamb, to death for treason.[4] Caton, Hopkins, and Lamb petitioned the Virginia General Assembly for a pardon, which was granted in the House but denied when submitted to the Virginia Senate.[5]

Under the Virginia Constitution of 1776, the Governor had the power to grant pardons, except where the House of Delegates prosecuted the individual, in which case only the House of Delegates had the power to grant a pardon.[6] The Virginia Treason Act, which was enacted later in 1776, indicated that a pardon for treason could only be granted with the consent of the General Assembly, which consisted of both the House of Delegates and the Senate.[7] Thus, the language of the Treason Act, enacted subsequent to the establishment of the Virginia Constitution, was in direct conflict with the Virginia Constitution.

On the day they were to be hanged, Caton, Hopkins, and Lamb presented the sheriff with a copy of the resolution from the House of Delegates pardoning them of treason.[8] This version of the resolution did not indicate that the Virginia Senate had refused to agree to the pardon.[9] The sheriff stayed the execution and kept the men in jail until the General Court could convene to decide the men’s fate in October 1782.[10]

Before the General Court, Virginia Attorney General Edmund Randolph requested a new order that the three men be executed.[11] In response, the prisoners produced the resolution of the House of Delegates, this time indicating in full that the Senate had rejected the pardon.[12] The defendants’ counsel argued that the pardon was valid under the Virginia Constitution, while the Attorney General argued that the pardon was invalid under the Treason Act because it lacked the consent of the state Senate.[13] In light of the “Novelty and difficulty” of the case, the General Court adjourned the case to Virginia highest court, the Court of Appeals.[14]

Arguments Before the Court of Appeals

The resolution of the question of whether the Court of Appeals had the power to invalidate an act of the General Assembly generated much debate among legal and social intellectuals.[15] Indeed, in letters and news reports it was known as “the great constitutional question.”[16]

Edmund Pendleton, as senior judge on the Court of Chancery, presided over the case.[17] The Court of Appeals convened on October 29, 1782, with argument being scheduled for the 31st.[18] In his account of the case, Pendleton identified three questions that the court should consider: (1) whether the Court of Appeals had jurisdiction to hear a capital criminal case, (2) whether a court of law could void a legislative act for violating the Constitution, and (3) whether the Treason Act violated the Virginia Constitution of 1776.[19]

Attorney General Edmund Randolph

Attorney General Edmund Randolph, argued on behalf of the Commonwealth that the Court of Appeals should not block the execution of the three prisoners. Surprisingly, according to notes sent to James Madison by Randolph himself, Randolph argued that a court did possess the authority to declare a statute unconstitutional but that, in this case, the statute and the Constitution were not inconsistent.

Under the interpretation of the Constitution urged by Randolph, the House of Delegates had the sole power of granting a pardon only where the House of Delegates had carried on a prosecution. In all other instances, the governor would enjoy the power to pardon, except where a law specifically directs otherwise.[20] Here, the Treason Act specifically directed that the General Assembly, not simply one branch of the legislature, had the right of granting pardons to persons convicted of treason.[21] According to Randolph, because the pardon of the House of Delegates was contrary to the statute, the pardon was invalid and the prisoners should be executed.[22]

Randolph’s opinions on judicial review revealed a distrust of the legislature as a flawed institution that could be subject to mob rule and tyranny if not held in check by a neutral, balanced judiciary.[23]

Andrew Ronald

Andrew Ronald served as counsel for Caton, Lamb, and Hopkins before the Court of Appeals. Ronald argued that review of legislative acts was a proper function of the judiciary.[24] He also urged the court to reject Randolph’s statutory interpretation arguments because the meaning of the constitution was clear.[25] “The act of assembly was contrary to the plain declaration of the constitution; and therefore void.”[26] If the constitutional language was considered ambiguous, Ronald urged the court to construe its interpretation in favor of lenity. Additionally, Ronald gave the judges an option for deciding the case without reaching the question of whether the statute violated the constitution: both the constitution and the act granted a separate pardoning power.[27]

Members of the Virginia Bar

In addition to inviting the arguments from the Commonwealth and the prisoners, Pendleton urged members of the Virginia Bar to set forth their opinions in court. Accordingly, three volunteers offered differing opinions as to whether a court could declare a legislative act unconstitutional. These three men were John Francis Mercer, future delegate from Maryland to the Constitutional Convention; William Nelson, later a judge of the Virginia General Court and professor of law at William and Mary; and St. George Tucker, author of an American version of Blackstone’s Commentaries and later judge at both the state and federal levels as well as professor of law at William and Mary. All three argued in support of the prisoners, and at least Tucker and Nelson expressed support for judicial review.[28]

Decision of the Court of Appeals

On November 2, 1782, the judges of the Court of Appeals delivered eight separate opinions.[29] Despite the range of arguments, the prisoners ultimately lost their appeal for freedom.[30] As to the substance of the eight opinions, there is some disagreement.[31]

Dispute over Reporting the Decision

Daniel Call reported the case as Commonwealth v. Caton, 4 Call 5 (1782), 51 years after the decision in 1833. It is unclear what sources Call used to report the case, but it is possible that Call referred to St. George Tucker’s notes on the decision.[32] The other detailed account of the case is from Edmund Pendleton’s report of the decision in his personal notes. Call’s report of Wythe’s opinion is consistent with Pendleton’s account but more detailed and, thus, “presumably accurate.”[33] It should be noted that Pendleton provided a detailed report of his own opinion but omitted any account of the other judges’ opinions, stating that “memory will not allow me to do Justice to the reasoning of the other Judges.”[34] Where Pendleton and Call are in dispute over how certain judges ruled, Pendleton’s remarks are likely more authoritative, as his notes were made at the time of the decision. Where Call reports Wythe’s opinion in detail, this is likely the best source for what Wythe’s statements and arguments were.

According to Pendleton, Judges James Mercer and Bartholomew Dandridge both ruled in favor of the prisoners, finding that the pardon from the House of Delegates was valid.[35] The six other judges, who ruled that the pardon was void, upheld the Treason Act as constitutional.[36] Of these six judges, only Peter Lyons wrote that a court could not review the constitutionality of a legislative act.[37] On the other hand, only two justices, James Mercer and George Wythe, declared support for judicial review.[38] Overall, although Wythe expressed a strong argument for the legitimacy and necessity of judicial review, the Caton decision cannot be said to have created a precedent for judicial review.[39] Indeed, a letter from Attorney General Randolph to James Madison on November 8, 1782, indicates that Randolph believed the court left undecided the matter of judicial review.[40]

Wythe’s Opinion

In Pendleton’s account of the case, he summarizes George Wythe’s opinion:

- Mr. Chan[cello]r George Wythe. At first doubted of the Jurisdiction but afterward expressed himself satisfied. Urged several strong and sensible reasons of the nature of those used by Lord Abblington, to

- prove that an Anti-constitutional Act of the Legislature would be void; and if so, that this Court must in Judgment declare it so, or not decide according the Law of the land. However that the Treason Act

- was not against the Constitution, and therefore the concurrence of the Senate was necessary to the Pardon of a Traitor, and this paper not a pardon.[41]

Wythe ultimately finds that the legislative act does not violate the Virginia Constitution, based on Randolph’s suggested constitutional interpretation, and consequently finds the prisoners’ pardon from the House of Delegates to be invalid. What makes Wythe’s opinion, as reported by Call, such an important historic legal document is his advocacy of the theory of judicial review.

The first part of Wythe’s opinion contains a forceful, dramatic argument for judicial review. In the wake of the colonial revolt against the British Crown, Wythe frames his discussion of judicial review in terms of tyranny and liberty: judicial review is an instrument of separation of powers that keeps each branch of government from gaining too much individual power. Wythe describes the judiciary as “tribunals, who hold neither [the power of the purse or the sword], are called upon to declare the law impartially between [the legislative and executive branches].”[42]

Through an anecdote about an English chancellor who declared it was his duty to protect individuals against government, Wythe wrote that the duty of the judiciary

- “is equally . . . to protect one branch of the legislature, and, consequently, the whole community, against the usurpations of the other: and, whenever the proper occasion occurs, I shall feel the duty; and, : fearlessly, perform it.”[43]

Taking the duty of the judiciary even further, Wythe delivers the most famous passage from his opinion:

- . . . if the whole legislature, an event to be deprecated, should attempt to overleap the bounds, prescribed to them by the people, I, in administering the public justice of the country, will meet the united powers, at my seat in this tribunal; and, pointing to the constitution, will say, to them, here is the limit of your authority; and, hither, shall you go, but no further.”[44]

In powerful language, evoking a dramatic image of the new nation's institutions clashing in the courtroom, Wythe positions the judiciary as a restrictive force preventing the rest of the government from overtaking its limits to the detriment of the populace. This indelible image of the judge as gatekeeper casts the relationship between the branches of government in stark terms and the judiciary as a coequal governmental power.

Caton v. Commonwealth is less about individual freedoms -- whether the prisoners should be pardoned for treason -- and more about how American government should be structured in light of a written constitution.[45] This early discussion of the respective powers of the branches of government, and how those powers would be defined and circumscribed, foreshadows later debates about the function of government. Indeed, the boldness of the Virginia judges in confronting unconstitutional acts of the legislature was praised by such leading statesmen as Patrick Henry and John Marshall during the Virginia Ratifying Convention, which met in June 1788 to discuss whether to ratify or reject the United States Constitution.[46]

The “great constitutional question” of judicial review would not be established at the national level until twenty-one years later, when Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, himself a student of Wythe’s at William and Mary, first exercised the power of judicial review at the federal level in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803). It was in Marbury that The Great Chief Justice held that federal courts are empowered to invalidate an act of Congress that is contrary to the United States Constitution.

See also

References

- ↑ The act creating the highest court in Virginia refers to it as simply the Court of Appeals, An Act Constituting the Court of Appeals, ch. XXII Laws Va. (1779), in 10 Hening's Statutes at Large 91 (1819), although later sources call it the Supreme Court of Appeals. Thomas Jefferson Headlee, Jr., The Virginia State Court System, 1776-: A Preliminary Study of the Superior Courts of the Commonwealth with Notes Concerning the Present Location of the Original Court Records and Published Decisions 7 (Va. State Lib. 1969).

- ↑ Commonwealth v. Caton, 8 Va. (4 Call) 5, 5 n. ‡ (1782).

- ↑ See Bradley Chapin, The American Law of Treason: Revolutionary and Early National Origins, 60-62 (Univ. Wash. Press 1964).

- ↑ David John Mays, 2 Edmund Pendleton, 1721-1803: A Biography vol. 2 189 (Harv. Univ. Press 1952).

- ↑ Edmund Pendleton, Pendleton’s Account of “The Case of the Prisoners” (Caton v. Commonwealth) (Oct. 29, 1782), in 2 The Letters and Papers of Edmund Pendleton 416 (David John Mays, ed., 1967).

- ↑ Va. Const. of 1776, art. IX, reprinted in WILLIAM W. HENING, 9 THE STATUTES AT LARGE: BEING A COLLECTION OF ALL THE LAWS OF VIRGINIA, FROM THE FIRST SESSION OF THE LEGISLATURE IN THE YEAR 1619 115-116 (1821).

- ↑ An Act Declaring What Shall Be Treason, 1776 Va. Acts ch. III, reprinted in WILLIAM W. HENING, 9 THE STATUTES AT LARGE: BEING A COLLECTION OF ALL THE LAWS OF VIRGINIA, FROM THE FIRST SESSION OF THE LEGISLATURE IN THE YEAR 1619 168 (1821).

- ↑ Pendleton, supra n. 4, at 417.

- ↑ Pendleton at 417.

- ↑ Pendleton at 417.

- ↑ Pendleton at 417.

- ↑ Pendleton at 417.

- ↑ Pendleton at 417.

- ↑ Pendleton at 417.

- ↑ William Michael Treanor, The Case of the Prisoners and the Origins of Judicial Review, 143 U. Penn. L. Rev. 491, 504 (1994).

- ↑ See Treanor, n. 45.

- ↑ See Treanor, n. 41.

- ↑ Pendleton at 417.

- ↑ Pendleton at 417.

- ↑ Treanor at 510.

- ↑ An Act Declaring What Shall Be Treason, supra n. ???

- ↑ See Treanor, 506-507 for citation to arguments made by Randolph.

- ↑ Treanor at 518-519.

- ↑ Caton at 7.

- ↑ Caton at 7.

- ↑ Caton at 7.

- ↑ Pendleton at 418.

- ↑ See Treanor at 521.

- ↑ See Treanor footnote 160.

- ↑ Caton at 20.

- ↑ Treanor at 529.

- ↑ Treanor at 532.

- ↑ Treanor at 532.

- ↑ Pendleton at 418.

- ↑ Pendleton at 426.

- ↑ Pendleton at 426-427.

- ↑ Pendleton at 426.

- ↑ Pendleton at 426-427.

- ↑ Treanor at 531.

- ↑ Letter from Edmund Randolph to James Madison (Nov. 8, 1782), in 5 MADISON PAPERS, supra note 8, at 262, 263 (“The judges of the court of appeals avoided a determination, whether a law, opposing the constitution, may be declared void, in their decision of Saturday last.”).

- ↑ Pendleton at 426-427.

- ↑ Caton at 7.

- ↑ Caton at 8.

- ↑ Caton at 8.

- ↑ Suzanna Sherry, The Founders’ Unwritten Constitution, 54 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1127, 1145 (1987).

- ↑ See Patrick Henry, The Virginia Convention: Thursday, 12 June 1788, in 10 THE DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF THE RATIFICATION OF THE CONSTITUTION 1219 (John P. Kaminski et al. eds., 1993) (footnote omitted) (“Yes, Sir, our Judges opposed the acts of the Legislature. We have this land mark to guide us.--They had fortitude to declare that they were the Judiciary and would oppose unconstitutional acts.”); John Marshall, Id. at 1431 (.