Difference between revisions of "Wythe's Lost Papers"

m |

m (→1824) |

||

| Line 245: | Line 245: | ||

[[File:JeffersonToWytheSeptember161787p1.jpg|left|thumb|200px|<p>"Thomas Jefferson to Wythe, 16 September 1787, pg 1." Image from the [http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib002952 Library of Congress,] ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers.''</p>]] | [[File:JeffersonToWytheSeptember161787p1.jpg|left|thumb|200px|<p>"Thomas Jefferson to Wythe, 16 September 1787, pg 1." Image from the [http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib002952 Library of Congress,] ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers.''</p>]] | ||

<div style="overflow: hidden;"> | <div style="overflow: hidden;"> | ||

| − | Major [[William DuVal]] was still in possession of some or all of Wythe's correspondence in 1824. | + | Major [[William DuVal]] was still in possession of some or all of Wythe's correspondence in 1824. On March 17, DuVal wrote to Thomas Jefferson, forwarding a manuscript copy of Wythe's address to the Hessian mercenaries from the Second Continental Congress, in 1776. DuVal mentions rumors of Wythe's papers still extant, including a manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence in Jefferson's hand, which may have been removed without his knowledge by Dr. Samuel McCraw, of Richmond, who was helping appraise Wythe's estate in 1806. From Dr. McCraw's widow, DuVal recently learned the papers may have been given to William Wirt. DuVal suggests writing to Wirt, and later sends Jefferson a letter regarding the papers for Jefferson to enclose with his own. It is unknown whether Jefferson then wrote to Wirt. |

| + | |||

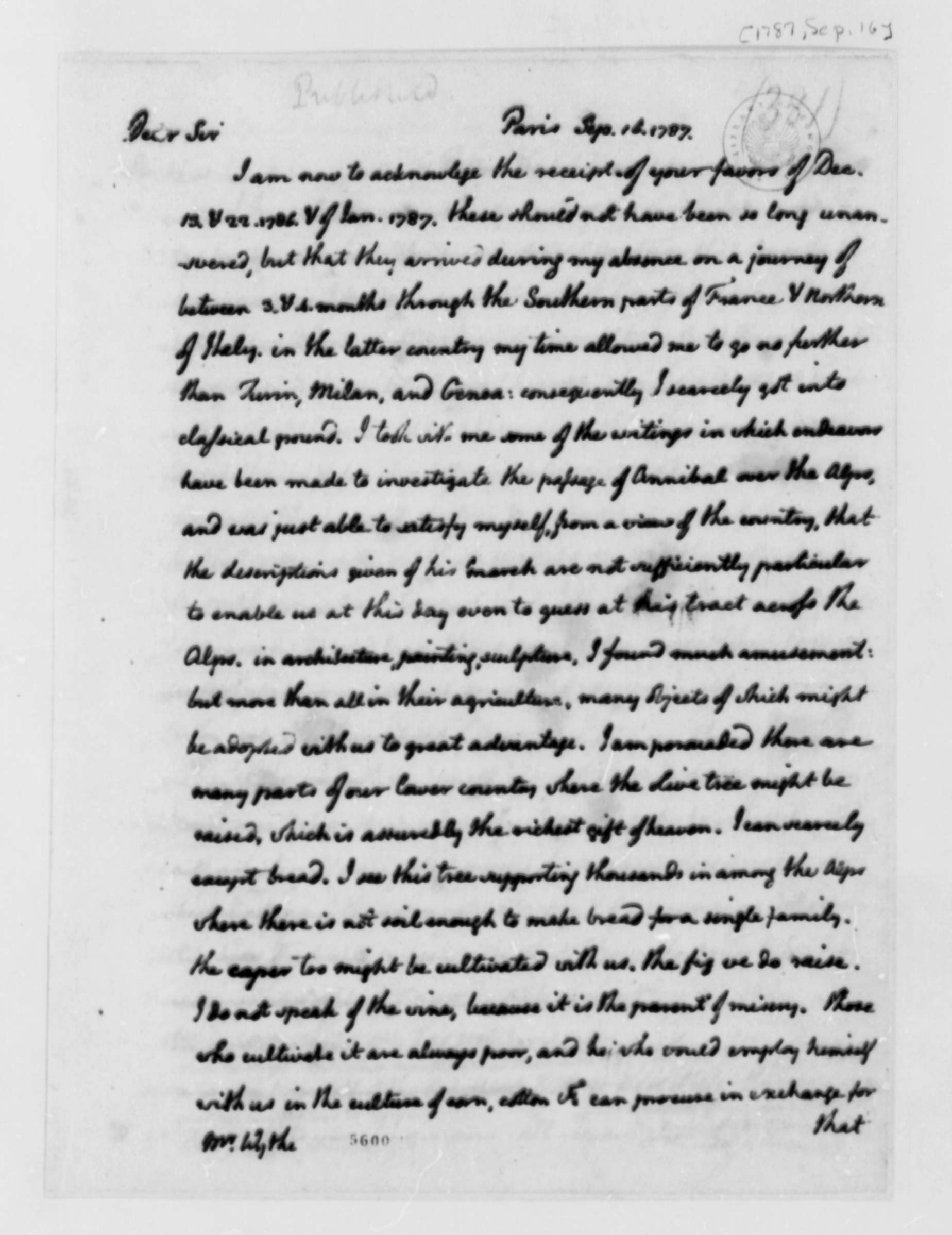

| + | In a letter from July of the same year, DuVal enclosed a [[Thomas Jefferson to Wythe, 16 September 1787|letter Jefferson sent to Wythe from Paris in September, 1787]], in which Jefferson briefly discusses States' rights:<ref>[http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib002952 Thomas Jefferson to Wythe, 16 September 1787,] in ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1 General Correspondence 1651-1827,'' (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1974).</ref> DuVal states that he has not shown Wythe's correspondence to anyone: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 13:40, 6 June 2024

|

Timeline for Wythe's Papers |

|

Before his death in June, 1806, George Wythe made no special instruction as to what should become of his personal papers and correspondence (if indeed he kept any). His last will and testament, dated April 20, 1803 (with later codicils), name his friend and neighbor William DuVal as executor, with allowances for his servants Lydia Broadnax and Michael Brown. He gives "Thomas Jefferson my silver cups and gold headed cane, and to my friend William Duval my silver ladle and table and teaspoons." To Thomas Jefferson he also wills "my books and small philosophical apparatus... the most valuable to him of any thing which i have power to bestow."[1] DuVal also had possession of two of Wythe's account books, apparently sent to Jefferson by mistake after Wythe's death, and which were returned.[2]

No great cache of papers appeared after Wythe's death, though Jefferson says (or assumes) that there were some papers.[3] Wythe's notebook of Greek vocabulary from the Iliad ended up in the possession of John Page (1743-1808), though when exactly this exchange took place is not recorded. Wythe's lectures from time as Professor of Law and Police at the College of William & Mary survived in manuscript, as well as drafts of the proposed Constitution for Virginia, and Declaration of Independence, which Jefferson had given Wythe in 1776. These drafts were transcribed and printed shortly after Wythe's death in Thomas Ritchie's Richmond Enquirer. DuVal loaned the documents to Ritchie for publication, along with Wythe's lecture notes from his time as professor of law. Ritchie wrote to Governor William Cabell in 1807, returning "valuable papers," presumably the Jefferson manuscripts.[4]

Governor John Tyler, Sr., however, wrote to Jefferson in 1810, to say that Ritchie was still in possession of Wythe's lectures. Jefferson politely refused to take possession of the manuscript, though he seemed surprised that Wythe had not destroyed the notes, "as I expect he has done a very great number of instructive arguments delivered at the bar, and often written at full length." His instructions were that the notes should "go, with his other papers to his executor," Major DuVal. Judge Spencer Roane, Wythe's former student, is suggested as one who could "send them to posterity," but this is the last time mention of the lecture notes appear.

Wythe's manuscript copies of the proposed Virginia Constitution and Declaration of Independence later came into the possession of Cassius Francis Lee, Jr., Esq. (1844–1892),[5] of Alexandria, Virginia, in the late nineteenth century, although how Lee obtained them is unclear.[6] In his preface to Lee of Virginia, 1642-1892, Edmund Jennings Lee says of his brother, Cassius:

Wythe's Iliad notebook was donated to the Virginia Historical Society by John Page, Jr., in 1834. It is unknown what became of Wythe's lecture notes, despite scholars Hemphill and Kirtland's attempts to track them. Both Worthington C. Ford and Paul L. Ford credit Cassius F. Lee, Jr. with providing them access to (evidence strongly suggests) Wythe's copies of Jefferson's manuscripts of the Constitution of Virginia and Declaration of Independence, which now reside at the New York Public Library's Archive and Manuscripts Division.

1776

- Main article: Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, 27 July 1776

Thomas Jefferson gives a draft of his Constitution for Virginia to George Wythe in Philadelphia, for Wythe to convey to Edmund Pendleton and the Virginia Convention.[9] Wythe leaves Philadelphia in the company of Richard Henry Lee on June 13, 1776, and arrives in Williamsburg on June 23, but the committee had already voted to adopt the plan put forth by George Mason:[10]

"I had not reached this place before the appointment of delegates. An attempt to alter it as to you was made in vain. When I came here the plan of government had been committed to the whole house. To those who had the chief hand in forming it the one you put into my hands was shewn. Two or three parts of this were with little alteration, inserted in that: but such was the impatience of sitting long enough to discuss several important points in which they differ, and so many other matters were necessarily to be dispatched before the adjournment that I was persuaded the revision of a subject the members seemed tired of would at that time have been unsuccessfully proposed. The system agreed to in my opinion requires reformation."[11]

Between July 4 and July 10, 1776, Jefferson makes handwritten copies of the Declaration of Independence and gives them to George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Philip Mazzei, John Page, Sr., and Edmund Pendleton.[12]

1806

Richmond Enquirer, June 20, 1806

- Main article: Richmond Enquirer, 20 June 1806

Following the death of George Wythe, Thomas Ritchie prints the text of a Jefferson draft of the Declaration of Independence, and a draft of the Virginia Constitution, in the Richmond Enquirer:[13]

Among the literary reliques of the venerable George Wythe, were found the following rare and curious papers in the hand of Mr. Jefferson. The first is a copy of the original declaration of our Independence, as it came from the hands of its author: The other is a Bill of Rights and of a Constitution for Virginia, composed by Mr. Jefferson. For the permission to peruse and publish these papers, we are indebted to the politeness of Major DuVal, the sole executor of the estate.

The federal assertion that Mr. Jefferson was not the author of this celebrated declaration, has long since been refuted, or else these papers would have furnished the most abundant refutation. What now will become of the no less unfounded assertion, that this paper as it was adopted by Congress, owes much of its beauty and its force to the committee appointed to draft it? The world will see that not only were very few additions made by the committee, but that they even struck out two of the most forcible and striking passages in the whole composition. For what reasons, yet remains to be discovered.

The passages omitted from the original are printed in Italics.

This Bill and Constitution as we have them in manuscript, are without any mark to note the date of their production. It is presumed however, that they were written in 1776. The constitution, written by Mr. Jefferson, in '83, is already printed in some of the Editions of his "Notes on Virginia."

Jefferson-DuVal correspondence, December 1806

- Main article: Jefferson-DuVal Correspondence

As executor of George Wythe's estate, William DuVal sent Wythe's library to Thomas Jefferson in September of 1806. Jefferson created at least one inventory of Wythe's library, for dispersing duplicate copies. DuVal accidentally included two "folio volumes of Mr. Wythe's accounts," which Jefferson returned. Jefferson and DuVal also mention two "profiles" of Wythe, one of which belonged to Lydia Broadnax. Wythe's fee books have not been found.

Dear Sir

Washington Dec. 4. 06

Your favor of Nov. 21. has been duly received and I thank you for the offer of the profile of Mr. Wythe, every trace of whom will be dear to me. If you will be so good as to desire Mr. Jefferson to forward me either the original or the copy, as you please, it will be received with equal thankfulness. It should be rolled on a stick, & not folded. The original of the other profile, after taking a copy, I had packed in a box addressed to yourself that it might be returned to Lydia with my thanks for the opportunity of copying it. In the same box I put 2 folio volumes of Mr. Wythe's accounts which had come by mistake with his books. The box I directed to be forwarded to you. Accept my friendly salutations & assurances of great respect.

Th: Jefferson

Wm.DuVal esq.

Dear Sir,

Richmond Decemr 10.th 1806

I received your favor of the 4th Instant. The origional [sic] profile of our Friend Mr George Wythe set in a plain neat Frame is this day delivered to Mr George Jefferson to be conveyed to to [sic] Washington for you Sir —

I received the other profile of our good and Virtuous Friend with the two folio fee Books which were packed up thro' mistake for which I return you my thanks—

You have perhaps seen the Resolution of the Assembly, respecting the House who have agreed to ware [sic] Mourning for one Month as a Mark of Respect for so great and good a Man.

I think they should have done more for an incitement to Virtue and Patriotism. I would have had them to have erected at the public Expence a plain Tomb Stone, to transmit to future ages the High Lines they entertained of his Talents, his Patriotism, and his inflexible Integrity — his was a rare Character, such an One as is scarcely to be met with in many Centuries

I am, Sir, with great esteem & Respect,

your mo. Obt Servt

William DuVal

1807

Ritchie to Governor William Cabell, April 25, 1807

In the Calendar of Virginia State Papers (1890),[14] is found the following letter from Thomas Ritchie, publisher of the Richmond Enquirer:

Page 511

THOMAS RITCHIE TO THE GOVERNOR.

April 25

The accompanying valuable papers were (last year) put into my possession by Major DuVall [sic] (acting Executive of Mr. Wythe), and I was by him requested to have them deposited among the archives of the Council. I do myself the peculiar pleasure of transmitting them to you for this purpose.

I am, &c.

[The above-mentioned papers were not found.—ED.]

- Read this book in Google Books.

1810

Jefferson-Tyler correspondence, November 12, 1810

- Main article: Jefferson-Tyler Correspondence

Governor John Tyler, Sr., wrote to President Thomas Jefferson in 1810,[15] to inform him that Thomas Ritchie was still in possession of George Wythe's manuscript lecture notes, and to ask if Jefferson would like to edit and publish them. Tyler mentions that Judge Spencer Roane, a former student of Wythe's (and Ritchie's cousin), has read the notes.

Letter from Virginia governor, John Tyler, Sr., to Thomas Jefferson, November 12, 1810, explaining that Thomas Ritchie is still in possession of George Wythe's lecture notes.

Image from Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

Richmond, Nov. 12, 1810

Dear Sir,

Perhaps Mr. Ritchie, before this time, has informed you of his having possession of Mr. Wythe's manuscript lectures delivered at William and Mary College while he was professor of law and police at that place. They are highly worthy of publication, and but for the delicacy of sentiment and the remarkably modest and unassuming character of that valuable and virtuous citizen, they would have made their way in the world before this. It is a pity they should be lost to society, and such a monument of his memory be neglected. As you are entitled to it by his will (I am informed), as composing a part of his library, could you not find leisure time enough to examine it and supply some omissions which now and then are met with, I suppose from accident, or from not having time to correct and improve the whole as he intended?

Judge Roane has read them, or most of them, and is highly pleased with them, thinks they will be very valuable, there being so much of his own sound reasoning upon great principles, and not a mere servile copy of Blackstone and other British commentators,—a good many of his own thoughts on our constitutions and the necessary changes they have begotten, with that spirit of freedom which always marked his opinions.

I have not had an opportunity of reading them, which I would have done with great delight, but these remarks are made from Judge Roane's account of them to me, who seemed to think, as I do, that you alone should have the sole dominion over them, and should send them to posterity under your patronage.

It will afford a lasting evidence to the world, among much other, of your remembrance of the man who was always dear to you and his country. I do not see why an American Aristides should not be known to future ages. Had he been a vain egoist his sentiments would have been often seen on paper; and perhaps he erred in this respect, as the good and great should always leave their precepts and opinions for the benefit of mankind.

Mr. Wm. Crane gave it to Mr. Ritchie, who I suppose got it from Mr. Duval, who always had access to Mr. Wythe's library, and was much in his confidence.

I hope you are quite as happy as mortality is susceptible of, though not quite dissolved; and that you may remain so for many years, is the sincere wish of your most obedient humble servant.

Jn. Tyler

1813

Niles' Weekly Register, July 3, 1813

- Main article: Weekly Register, 3 July 1813

In celebration of July Fourth, 1813, the Weekly Register prints the Declaration of Independence side-by-side with the text of Jefferson's draft published in the Richmond Enquirer of 1806.[16]

< 1817

William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry

- Main article: Life of Patrick Henry

In his biography of Patrick Henry, in a footnote regarding the Virginia Convention of 1776, William Wirt asserts that he saw (sometime after Wythe's death in 1806, but before the book's publication in 1817) an "original rough draught of a Constitution for Virginia, in the hand-writing of Mr. Jefferson" in the Virginia state archive:

Page 196n

* The striking similitude between the recital of wrongs prefixed to the constitution of Virginia, and that which was afterwards prefixed to the declaration of independence of the United States, is of itself sufficient to establish the fact that they are from the same pen. But the constitution of Virginia preceded the declaration of independence, by nearly a month; and was wholly composed and adopted while Mr. Jefferson is known to have been out of the State, attending the session of congress at Philadelphia. From these facts alone, a doubt might naturally arise whether he was, as he has always been reputed, the author of that celebrated instrument, the declaration of American independence, or at least a recital of grievances which ushers it in; or whether this part of it at least, had not not been borrowed from the preamble to the constitution of Virginia. To remove this doubt, it is proper to state, that there now exists among the archive of this state, an original rough draught of a Constitution for Virginia, in the hand-writing of Mr. Jefferson, containing this identical preamble, and which was forwarded by him from Philadelphia, to his friend Mr. Wythe, to be submitted to the committee of the house of delegates. The body of the constitution is taken principally from a plan proposed by Mr. George Mason; and had been adopted by the committee before the arrival of Mr. Jefferson's plan: his preamble however, was prefixed to the instrument; and some of the modifications proposed by him, introduced into the body of it.

1822

Richmond Enquirer, August 6, 1822

- Main article: Malignity Exposed

A comment in the Richmond Enquirer in August of 1822, reprinting another article from the Charleston Patriot, is cited by John H. Hazelton as proof that Jefferson had sent a draft copy of the Declaration of Independence to George Wythe,[17] before the 1806 article in the Enquirer had been found. The article extracts a letter from someone claiming to have a Jefferson draft of the Declaration, who could only be the Rev. R.H. Lee.

Page 3

At least thirteen years ago we published in this paper a copy of the original draft as it came from his [Jefferson's] own hands: This copy was in his handwriting, and was found among the papers of the late Mr. Wythe, the friend and instructor of his early years. This copy was published in Niles's W. Register, & in various other newspapers of this continent. And now forsooth, we are to be amused with a new discovery of the original draft being "scored and scratched like a school-boy's exercise."

1824

"Thomas Jefferson to Wythe, 16 September 1787, pg 1." Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

< 1829

B.W. Leigh, Proceedings and Debates of the Virginia State Convention of 1829-1830

In the Proceedings and Debates of the Virginia State Convention of 1829-1830[20] on November 3, 1829, during a debate on the state constitution at the Virginia State Convention, Benjamin Watkins Leigh states that he has seen Jefferson's proposed draft for the Virginia Constitution in the council chamber in the Capitol in Richmond, but that "it cannot now be found."

Page 160

At what period Mr. Jefferson discovered the incompetency of the Convention of '76. it were vain to conjecture—but I apprehend, it was not during the session of that body—for I know that Mr. J. himself prepared a Constitution for Virginia, and sent it to Williamsburg that it might be proposed to the Convention, during the session, from which the preamble and nothing more, was taken and prefixed to the present Constitution. Anyone may see, at a glance, that that preamble was written by the author of the Declaration of Independence. I have seen the projet [sic] of the Constitution, which Mr. J. offered, in the council chamber, in his own hand writing, tho' it cannot now be found—and I have since cursed my folly that I neglected to take a copy of it, in order to compare Mr. J's democracy of that day, with George Mason's practical republicanism. But, Sir, the validity of the Constitution, as such, has been maintained by Pendleton, Wythe, Roane, by the whole Commonwealth for fifty-four years.

- Read this book in Google Books.

1834

John Page, Jr., January 3, 1834

- Main article: John Page, Jr., to James E. Heath, 3 January 1834

Page inherited George Wythe's etymological praxis—an autograph notebook of Greek vocabulary from Homer's Iliad with Latin equivalents—from his father, John Page, Sr. (1743 – 1808), and in 1834 donated it to the Virginia Historical Society, in Richmond:

I herewith send you the book which I promised you for your Society. It was (as I informed you) the property of the late venerable and learned Chancellor Wythe, and I believe is altogether in his hand writing, though the character of the copy from "Sir John's Breviate Book" seems to be different from that of the Greek and Latin. Much the longest portion of the book is a Clavis Oμηρŏ or Etymological Praxsis on several of the books the Iliad, and some of the Ραψωίδία, which will serve in a striking manner to illustrate the great industry of that distinguished man.[21]

1842

Major William DuVal died on January 3, 1842, at his plantation in Buckingham County, at the age of 94.

< 1848

Alexander H. Everett, The Library of American Biography

Alexander H. Everett wrote a biography of Patrick Henry for the first volume of the second series of Jared Sparks' Library of American Biography, published in 1848. In his reporting of Henry's participation in the Fifth Virginia Convention of 1776, Everett mentions that "the plan of government, which he [Jefferson] transmitted to Mr. Wythe, including the Declaration as it now stands in the statute-book, are still preserved, in Mr. Jefferson's hand-writing, in the archives of Virginia."[22]

Since Benjamin Watkins Lee reported the draft of the constitution for Virginia missing before 1829, Everett may have been parroting the earlier research of Wirt and others (although Wirt makes no mention of the Declaration). Everett died in June, 1847.

- Read this book at HathiTrust.

1861

Edmund Jennings Lee, Lee of Virginia, 1642-1892

In his genealogical history of the Lee family, Edmund Jennings Lee (1853 – 1922)[23] publishes an 1861 letter from the Reverend Richard Henry Lee, a response to a request from Cassius Francis Lee, Jr. (Edmund's older brother, 17 years old at the time), for autographs of the "patriots of the Revolution." The Reverend tells his young cousin that he has given away (apparently donated) "every MSS., until I have not one left":

Page 395

REV. RICHARD HENRY LEE.

44. Richard Henry6 the eldest son of Ludwell Lee5 (Richard Henry4, Thomas3 Richard2, Richard1) and Flora Lee, his first wife, was born the 23d of June, 1794, and died at Washington, Pa., the 3d of January, 1865. He was twice married, and had issue by each marriage. Mr. Lee was educated at Dickinson College, Pa., where he graduated with the honors of his class. He then studied law with the late Judge Thomas Duncan, of Carlisle, Pa., and began the practice of his profession in Loudoun county. While residing at Leesburg he edited the Memoirs of his grandfather, Richard Henry Lee, and of his great-uncle, Dr. Arthur Lee, which were issued in 1825 and 1829 respectively. He was also at one time Mayor of Leesburg. Mr. Lee was a scholar, especially accomplished in classical literature and belles-lettres; he read Greek and Latin authors with ease, and, having a fine memory, treasured up their beauties for frequent reference. In 1833 he was called to the Chair of Languages at Washington College, Pennsylvania, and in 1837 was transferred to that of Belles-

Page 396

Lettres. During his occupancy of these professorships he continued the practice of law. But in 1854 he gave up the law and resigned his professorship to begin the study of theology, with a view to entering the ministry of the Episcopal Church, which he did in 1858, and assumed charge of Trinity Church, Washington, Pa. He was in charge of that church at the time of his death.

Writing to the late Cassius F. Lee, Jr., under date of 18th of November, 1861, Mr. Lee told of his disposal of the various MSS. used by him in the preparation of the Memoirs. He wrote:

"My Dear Cousin: When your letter of the 24th ult. reached here I was in Philadelphia, and since my return I have been suffering from a severe cold, which, together with current duties, has delayed this reply.

"I am happy to see from your letter that you are cherishing a veneration for the great and wise patriots of the Revolution, and greatly regret it is out of my power to gratify your desire to possess their autographs. I presented to the Athenæum in Pha.[24] all the MSS. from which I composed our Grandfather's Life; and to the University of Cambridge all those I used in the Life of our Uncle Arthur. Some years after I presented to the University of Virginia all the rest. I had selected some for my sons; but the many applications continually made to me, from every part of this country and Europe, led me to give away, one after another, every MSS., until I have not one left, to the excessive regret, now, of my sons and myself.

"Present my affectionate regards to your Father and Uncle Charles. You will greatly oblige me by letting me hear about Cousin Edmund I. Lee and his family, and of Cousin R. H. Lee. In these deplorable times I am anxious to hear of them. I hope your mother has recovered. I heard in Trenton, N. J., of her illness."

- Read this book in the Internet Archive.

1890

Worthington C. Ford, The Nation, August 7, 1890

- Main article: Jefferson's Constitution for Virginia

Ford describes two manuscript drafts of the Virginia Constitution, found near Lexington, Virginia:[25]

Page 108

The fact remains that for more than a century Jefferson's draft has been lost, and it has only recently been discovered near Lexington—two copies of it, both in Jefferson's MS., one with and the other wanting the preamble. Is it too great a stretch to conjecture that one, at least, was the identical manuscript that Wythe carried to Pendleton?

The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, January, 1891

The New England Historical and Genealogical Register for January, 1891, reporting the proceedings of state historical societies, reveals that Cassius F. Lee, Jr., displayed a photographic reproduction of a Jefferson draft of the proposed Constitution for Virginia, at the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, in November, 1890.[26] The quoted text of the document matches Wythe's copy (Jefferson's third and final draft), printed in the Enquirer in 1806:

Page 94

SOCIETIES AND THEIR PROCEEDINGS.

VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY.Richmond, Saturday, Nov. 1, 1890.—A meeting of the executive committee was held in the‘ society’s rooms, Westmoreland Club House, Vice-President Henry in the chair.

A photograph of the Constitution of Virginia, proposed by Thomas Jefferson in the Virginia Convention of 1776—a document until recently supposed to be lost—presented by Mr. Cassius F. Lee, Jr., of Alexandria, was exhibited. The document was labelled by Jefferson, "A bill for the new modelling of the form of government and for establishing the fundamental principles thereof in future." Other valuable donations were reported by Mr. Brock the librarian.

- Read this article in Google Books.

< 1892

"Historic Manuscript Found in a Garrett," January 6, 1901

- Main article: "Historic Manuscript Found in a Garret"

Before his death in 1892, several years prior to the writing of this article for the New York Times, Cassius F. Lee, Jr., of Alexandria, Virginia, sells a Jefferson draft of the Declaration to Elliot Danforth, of New York. Danforth sells it to Dr. Thomas A. Emmet, whose collection of Revolutionary War era manuscripts eventually goes to the New York Public Library.

1892

Kate Mason Rowland, "A Lost Paper of Thomas Jefferson," July, 1892

- Main article: Lost Paper of Thomas Jefferson

The text of the manuscript constitution for Virginia described by Worthington C. Ford is published, with a short commentary by Rowland, in the William & Mary Quarterly.[27]

September 4, 1892

Cassius F. Lee, Jr., dies in Alexandria, Virginia, aged 48.[28]

1893

Paul L. Ford, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson

In a footnote to the text of two drafts for the Virginia Constitution, Ford credits his younger brother, Worthington C. Ford, and Cassius F. Lee, for providing him with "photographic reproductions" of Jefferson's drafts. He also notes Wirt and Leigh's previous sightings of the "fair draft" of the state constitution in Jefferson's hand:[29]

Page 7

PROPOSED CONSTITUTION FOR VIRGINIA1 [June, 1776.] FIRST DRAFT[30] A Bill for new modelling the form of government and for establishing the Fundamental principles of our future Constitution

- Whereas George

king of Great Britain & Ireland and Elector of Hanover2

FAIR COPY[31] [A Bil]l for new-modelling the form of Government and for establishing the Fundamental principles thereof in future.

- Whereas George

Guelf king of Great Britain and Ireland and Elector of Hanover,

1 The fair copy is endorsed in Jefferson's handwriting, "A Bill for new modelling the form of government, & for establishing the fundamental principles thereof in future. It is proposed that this bill, after correction by the Convention, shall be referred by them to the people, to be assembled in their respective counties and that the suffrages of two thirds of the counties shall be requisite to establish it." The rough draft has no preamble, though space was left for it. In both copies the erasures and interlineations are indicated. The bracketed portions in Roman are so written by Jefferson. Those in italic are inserted by the editor. For these most important papers I am under obligation to the courtesy of Mr. Cassius F. Lee of Alexandria, Va., and Mr. Worthington Chauncey Ford, of Brooklyn, N. Y., not merely for photographic reproductions, but also for the facts concerning them given at large in his Jefferson's Constitution for Virginia (The Nation, LI, 107). This constitution, though mentioned in several of the histories and other works concerning Virginia, and though seen by Wirt (Life of Patrick Henry, p. 196), and by Leigh (Debates of Virginia Convention, 1830, p. 160), has never yet been printed or even quoted.

Page 42

Reproducing three identified copies of the Declaration of Independence, Ford notes that Jefferson sent copies to George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, John Page, Sr., Edmund Pendleton, Philip Mazzei, and "probably others":[32]

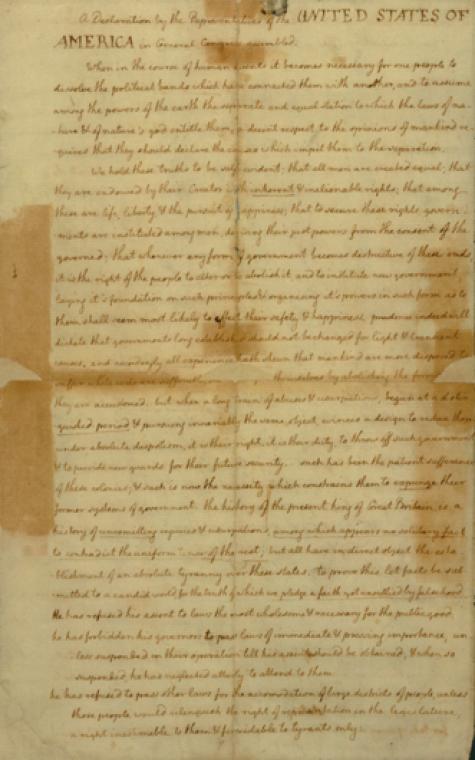

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE1 July 4, 1776. FIRST DRAFT. A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America in general Congress assembled.

REPORTED DRAFT. A Declaration by the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA in General Congress assembled.

ENGROSSED COPY. In Congress, July 4, 1776. The Unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America.

When in the Course of human Events it becomes necessary for a People to advance from that Subordination, in which they have

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have con-

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have con-

1 The text in the first column is from a copy in the handwriting of John Adams, now in the Adams papers at Quincy, for which I am indebted to the courtesy of Mr. Charles Francis Adams and Mr. Theodore F. Dwight. From a comparison of it with the fac-simile of Jefferson's rough draft, it is evident that it represents the first phrasing of the paper. The text in the second column is approximately that reported by the committee to Congress, and is taken from Jefferson's rough draft reproduced herein in fac-simile from the original in the Department of State. The text in the third column is from the engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence, also in the Department of State. Another MSS. copy in Jefferson's writing, slightly altered in wording, was inserted by him in his Autobiography, and is printed, ante, I, 30. This is in the Department of State, as is likewise a copy in his handwriting made for Madison in 1783, which is reproduced in facsimile in the Madison Papers, vol. III. Between July 4th-10th, Jefferson made copies of the Declaration, indicating his phrasing and that adopted by the Congress, and sent them to R. H. Lee, Wythe, Page, Pendleton, and Mazzei, and probably others. Lee gave his copy to the American Philosophical Society, where it now is. Those of Wythe, Page, and Pendleton have never been heard of. Mazzei gave his to the Countess de Tessie of France, and it has not been traced. A copy in Jefferson's writing is now owned by Dr. Thomas Addis Emmett, and a fragment of another is in the possession of Mrs. Washburn of Boston. Thus at least five copies and a fragment of a sixth are still extant. Cf. ante, 1, 30.

1894

Lenox Library accession

From the New York Public Library's record for Thomas Jefferson's proposed constitution for Virginia, June 1776:

This is the third and final draft and was printed in Paul Leicester Ford's The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, volume 2, page 7, where the history of this document is noted. The first and second drafts are in the Library of Congress. Autograph document, presented to the Lenox Library by Mr. Alexander Maitland in 1894.

See also Julian P. Boyd's note, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (1950):

The provenance of this text is given in a memorandum of Victor H. Paltsits (Ford Papers, NN, 1 Feb. 1916): the document was acquired from Cassius F. Lee, Jr., of Alexandria, by 'William Evarts Benjamin, then a well-known dealer of New York City who acted in the matter for some woman whose name is not revealed.' Alexander Maitland purchased it of Benjamin for the Lenox Library.

1897

Bulletin of the New York Public Library, December, 1897

In 1895, the New York Public Library was created from the consolidation of the Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. In the new Bulletin of the New York Public Library, an inventory of the Thomas Addis Emmet Collection, presented to the library by John S. Kennedy (president of the former Lenox Library) in June of 1896,[33] describes the "Cassius F. Lee" copy of the Declaration, which remains in the collections of New York's Archives and Manuscripts Division:[34]

Document: United States.—Congress, Continental, 1775-1789. [Philadelphia, July 4, 1776.] Declaration of Independence. Draft in the handwriting of Thomas Jefferson. 4 pp. F°. EM. 1524

This one of several fair copies made by Jefferson from the original rough draft of the Declaration, after its adoption and publication, in which be gave the wording of the text as reported by the Committee, with the portions underlined that were changed or rejected by Congress. After remaining in the possession of the Lee family, of Virginia for many years, with other papers of Jefferson, the manuscript was sold by the late Mr. Cassius F. Lee, of Alexandria, to Mr. Elliot Danforth, of New York, from whom Dr. Emmet obtained it.

The words substituted by Congress are not given in this copy, which in other respects agrees closely with the drafts sent to Lee and Madison, and with the text as incorporated in the autobiography, with the exception that two paragraphs and a few words were transposed.

Five other drafts of the Declaration in Jefferson's handwriting are known:—(I) the original rough draft, with interlineations, in the Department of State at Washington (reproduced a EM. 1523); (2) the copy lent to R. H. Lee in July 1776. and given by his grandson to the American Philosophical Society at Philadelphia in 1825, being similar to EM. 1524 (see EM. 1521); (3) the copy made for Madison in 1781, similar to the preceding, and now in the State Department (reproduced in fac-simile in the Madison Papers, vol. 3); (4) the draft incorporated in the autobiography of 1821, similar to (2) and (3), and also in the State Department (printed in Jefferson's Writings); and (5) the fragment belonging to Mrs. Washburn, of Boston. See Jefferson's Writings (Ford) vol. 2. p. 42, note.

It is stated by Jefferson, in a letter to Madison (Aug. 30, 1823), that be wrote a fair copy from the rough draft, reported it to the Committee, and from them unaltered, to Congress. All trace of this fair draft has been lost. It was probably used in crossing out the passages rejected by Congress, and in the making of the engrossed copy. The latter, which is the one that was signed, is in the keeping of the State Department.

Between July 4 and 10 Jefferson sent other drafts of the Declaration, with the omitted passages marked, to George Wythe, John Page, Edmund Pendleton, and Philip Mazzei, none of which has been found or identified. See Jefferson's Writings (Ford) vol. 2. p. 42, note.

- Read this article in Google Books.

1898

I. Minis Hays, "A Note on the History of the Jefferson Manuscript Draught of the Declaration of Independence...," January, 1898

An article in the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society describes a copy of a Jefferson draft of the Declaration of Independence given to the American Philosophical Society in 1825, from a grandson of Richard Henry Lee. Notes another draft at the Lenox Library in New York (absorbed by the New York Public Library), and doubts the Lenox copy came from R.H. Lee:

Page 101

5. A copy in the Emmet collection in the Lenox Library, New York. "This is one of several fair copies made by Jefferson from the original rough draught of the Declaration, after its adoption and publication, in which he gave the wording of the text as reported by the Committee, with the portions underlined that were changed or rejected by Congress. After remaining in the possession of the Lee family of Virginia for many years, with other papers of Jefferson, .... was sold by the late Mr. Cassius F. Lee, of Alexandria, to Mr. Elliot Danforth, of New York, from whom Dr. Emmet obtained it."1

I have not been able to learn the circumstances under which this copy came into the possession of the Lee family. Dr. Emmet writes me that the only information he "can give is that Mr. Lee stated to me that it was one of the copies Jefferson sent his grandfather, and that it had been sent to some one in lower Virginia by Richard Henry Lee shortly after, and that it was not recovered for many years after."2

This copy is without interlineation and does not contain the additions made by the Congress. It is, with some slight exceptions, the text of the document as reported to the Congress.

1 Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 1897, p. 355.

2 Personal communication, April 16, 1898. It does not seem likely that Jefferson should have sent two similar autographic copies of the Declaration to Richard Henry Lee, and as the history of the copy possessed by this Society is clear and indisputable, it is probable that the Emmet copy came from another source, and Mr. Paul L. Ford, the learned student of Jefferson's works, informs me that he is inclined to believe that it is the copy sent to John Page.

Page 102

In addition to these five copies and a fragment of a sixth, Jefferson made, according to Ford,1 between the 4th and 10th of July, other copies, which he sent to George Wythe,2 John Page, Edmund Pendleton and Philip Mazzei, who gave his copy, so so Jefferson states in his letter to Vaughan, to the Countess de Tessé of France, but is not known if these copies are still in existence.

1 Writings of Jefferson, ii , p. 42, Note.

2 This copy was delivered to Mr. Thomas Ritchie, editor of the Richmond Enquirer, by Major Duval, the executor of Mr. Wythe's estate, and its text was printed in Niles's Weekly Register, July 3, 1883 (Vol. iv, No. 13). Notwithstanding inquiry among Mr. Ritchie's descendants I have not been able to learn whether it is still in existence.

- Read this article in Google Books.

1906

John H. Hazelton, The Declaration of Independence: Its History

- Main article: Malignity Exposed

In an appendix to his history of the Declaration of Independence, Hazelton describes the various copies made by Jefferson which have been discovered, including the draft at the New York Public Library, which he supposes could have been Wythe's, Pendleton's, or Page's copy.[35]

Page 347

York Public

Library

(Lenox)

The copy in the New York Public Library (Lenox) was purchased from Dr. Thomas Addis Emmet of New York City. He secured it from Elliot Danforth of the same place, who purchased it from Cassius F. Lee of Alexandria, Va. Lee had written to both Emmet and Danforth, but Emmet's letter accepting the Declaration upon the terms proposed was not received until after Danforth had purchased it.

How it came into the hands of Lee is not known.

Danforth writes us that he cannot find the letters which he received from Lee, even if they are still in existence. Emmet writes us: "I did not preserve Mr. Lee's letters—" Lee died in 1892, and, so far as we can learn by corresponding with his daughter, Mrs. W. J. (Lucy Lee) Boothe, Jr., of Alexandria, left no record of the history of the manuscript (if he knew anything of it) among his papers.

Emmet writes, however, to Hays (Hays says): "Mr. Lee stated to me that it was one of the copies Jefferson sent his grandfather, and that it had been sent to someone in lower Virginia by Richard Henry Lee shortly after, and that it was not recovered for many years after"; but this, we think, cannot be true, unless Jefferson sent it with some other letter than that (See p. 344) of July 8, 1776, which seems scarcely possible.

It may very well be the copy113 which Jefferson mailed to Pendleton or the one114 found among the papers of Wythe or, if there ever was such a copy, the copy115 mailed to Page.

It also is in the handwriting of Jefferson and fills the front and reverse sides of two sheets of foolscap; and the paper itself is of the same character and size as that used for the draft which he sent to R. H. Lee. Indeed, pages 1, 2 and 4 respectively of these two drafts end upon the same word; while page 3 of this copy ends with the word "altering" and of the copy sent to Lee with "altering fundamentally the forms of our governments;": from which it might appear that one was copied from the other. The individual lines, however, as well as the underscored words, as we have seen, do not always correspond; and there is sometimes an "and" in one where there is an "&" in the other and an occasional slight difference in punctuation. There is no indorsement—or, indeed, any extra-

Page 348

neous writing—upon it as there is upon the copy which was sent to Lee. It has at some time been folded once each way.

Page 350

to

Wythe

Another draft in the handwriting of Jefferson which has not been located—unless it is the one in the New York Public Library (Lenox) or the one in the Massachusetts Historical Society—would seem120 to have been sent to Wythe; for the Richmond Enquirer121 (C) of August 6, 1822, says:

MALIGNITY EXPOSED.

The subjoined article from the Charleston Patriot exposes another of the vile attempts, which have been recently made by a sleepless spirit of resentment, to strip the laurel from the brow of Jefferson... At least thirteen years ago122 we published in this paper a copy of the original draft123 as it came from his own hands: This copy was in his handwriting, and was found among the papers of the late Mr. Wythe, the friend and instructor of his early years. This copy was published in Niles's W. Register, & in various other newspapers of this continent. And now forsooth, we are to be amused with a new discovery of the original draft being "scored and scratched like a school-boy's exercise." This is a most miserable exaggeration—the variations, which were made, were most of them disapproved of by the author we recollect those passages well—and we repeat what we said at the time of re-publication, that the paper was altered for the worse...

[From the Charleston Patriot.]

This would appear to be an age of calumny and all uncharitableness... But as if malice is contagious or admits of being propagated, a coadjutor to the "Native of Virginia" has appeared in the Federal Republican, whose article will be found below, and who wishes to rob Mr. Jefferson of the fume of having solely written the Declaration of Independence.

—Richard Henry Lee is credited with the honor of having moved the Declaration, and of having corrected and amended the original report of this celebrated paper. Mr. Jefferson is not denied having furnished the outlines of the Declaration, but it is pretended that it is the work as it now stands of abler hands. Now, the plain intent of this fresh or forgotten fragment of history just recovered and brought to light, is to deprive Mr. Jefferson of all credit for originality in drawing up the Declaration of Independence... The credit of being the author of the Declaration is nowise impaired by the subject being moved by another; but the insinuation that the original draft only was furnished by him and not the perfect copy as it now stands, is contradicted by the evidence of contemporaries. Let us see these promised documents...

Page 351

[From the Philadelphia Union.]

We have long been acquainted with the facts alluded to in the following article from the Federal Republican. We have seen Mr. Jefferson's draft124 of the Declaration of Independence, scored and scratched like a school boy's exercise. When Mr. Schæffer shall comply with his promise to publish the documents relating to this subject, the jack daw will be stript of the plumage, with which adulation has adorned him, and the crown will be placed on the head of a real patriot.

Richard Henry Lee.—It is truly remarkable that this great statesman is forgotten among all of the celebrities of the Fourth of July. It is to this "illustrious" patriot, we are indebted for our Declaration of Independence, for it was he who moved it in Congress... Among men of sense, candor and truth, there will be no question whether he who dared openly to propose the project, or he who had the principal agency in putting it on paper deserves the most credit...

Ere long, we hope to have leisure to publish some very important documents on this subject. We have the very copy125 of the declaration of independence, as it was originally reported and sent by the "illustrious penman," to this same Richard Henry Lee together with his remarks126 on it in his own hand writing...[36]

[Fed. Rep.The Weekly Register (C and N) referred to—of July 3, 1813—says:

The time fitting the purpose, we embrace this occasion to present our readers with the Declaration of Independence, placing by its side the original draft127 of Mr. Jefferson, about which much curiosity and speculation has existed. The paper from which we have our copy, was found among the literary reliques of the late venerable George Wythe, of Virginia, in the hand writing of Mr. J. and delivered to the editor [Thomas Ritchie] of the Richmond Enquirer by the executor of Mr. Wythe's estate, major Duval. The passages stricken out of the original, by the committee, are inserted in italics.

Here follow in separate columns a copy (seemingly) of the Declaration as printed by Dunlap under the order of Congress and a copy128 (substantially) of it as submitted to Congress by the committee on June 28th. Below appears the following: "The Declaration as adopted was also signed."; and then come the names of the signers, except that of M:Kean, arranged by Colonies.

- Read this book in Google Books.

1916

Paltsits memorandum, February 1, 1916

Julian P. Boyd details the provenance of the New York Public Library's copy of Thomas Jefferson's proposed constitution for Virginia, June 1776 in volume one of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson (1950):[37]

The provenance of this text is given in a memorandum of Victor H. Paltsits (Ford Papers, NN, 1 Feb. 1916): the document was acquired from Cassius F. Lee, Jr., of Alexandria, by "William Evarts Benjamin, then a well-known dealer of New York City who acted in the matter for some woman whose name is not revealed." Alexander Maitland purchased it of Benjamin for the Lenox Library. Shortly after this text was brought to light in 1890, efforts were made to identify it as the copy that TJ had given to George Wythe to convey to the Virginia Convention (D. R. Anderson, "Jefferson and the Va. Const.," Amer. Hist. Rev., XXI [1915-1916], 751).

D.R. Anderson, "Jefferson and the Virginia Constitution," July, 1916

- Main article: Jefferson and the Virginia Constitution

An article in the American Historical Review suggests comparing the manuscript described by Worthington C. Ford in 1891 with the text published in The Enquirer in 1806.[38]

1943

Julian P. Boyd, The Declaration of Independence

In his excellent study with large, photographic reproductions of all of the various drafts of Jefferson's composition of the Declaration, Julian P. Boyd believes that "the copy in the New York Public Library is, in all probability, the copy sent to Wythe," but he cannot "conclusively" establish this as fact:[39]

Page 5

II. Jefferson's "First Ideas" on the Virginia Constitution, 1776

Reproduced from the first two pages of the first of three drafts of a constitution which Jefferson sent to the Virginia Convention. From the original in the Jefferson papers in the Library of Congress. The Library also has another copy, lacking the part reproduced here, which was a list of reasons for Virginia's repudiation of her allegiance to George III and which was not only incorporated in large part in the Virginia Constitution as its Preamble but was also followed closely by Jefferson in the corresponding part of the Declaration of Independence. The first draft is made up of six folio pages, being similar to another draft, likewise in Jefferson's handwriting, in the New York Public Library. The second draft was first published in Writings of Thomas Jefferson, P. L. Ford, ed., II, 7ff. The third copy, lacking the part contained in the two pages reproduced here, was presented to the Library of Congress in 1931. Both this copy and that in the New York Public Library came from Cassius F. Lee of Alexandria, Virginia. These drafts were probably written in the spring of 1776, and certainly before June 13, but there is no documentary evidence for supposing, as Fitzpatrick does, that they were drawn up after May 27; John C. Fitzpatrick, Spirit of the American Revolution, p. 2; see also, John H. Hazelton, The Declaration of Independence, New York, 1906, p. 146, 451-52. The first draft, reproduced here in actual size, is on a paper manufactured in Holland and bearing the watermark L V G [errevink?], which is different from the paper used by Jefferson in his various drafts of the Declaration, thereby lending strength to the supposition of a somewhat earlier composition than Fitzpatrick indicates.

Page 7

VII. Unidentified Copy of the Declaration Made by Jefferson [Cassius F. Lee Copy]

Reproduced from the original through the courtesy of the President and Board of Trustees of the New York Public Library, who also consented to place it on exhibit in the current Jefferson exhibit at the Library of Congress. This copy was purchased for the New York Public Library in 1896 from Dr. Thomas Addis Emmet, who in turn secured it from Elliot Danforth. The latter purchased it from Cassius F. Lee of Alexandria, Virginia. Since its early history is hidden in obscurity, the person for whom Jefferson made it is not known. In addition to the copy made for Richard Henry Lee, Jefferson sent other copies, which evidently were made between July 4 and July 10, to George Wythe, John Page, Edmund Pendleton, and Philip Mazzei. The present copy may be one of these, but this fact has not been positively established. See Hazelton, op. cit., p. 347-48. This copy corresponds closely to the Lee copy in respect to its contents: that is, it represents the Declaration approximately as it was when the Committee of Five reported it to Congress. See note below on the copy sent to George Wythe.

Page 8

Note on the Copy Sent by Jefferson to George Wythe

John H. Hazelton, in his invaluable pioneering study on the Declaration of Independence, quoted (p. 350) the Richmond (Virginia) Enquirer of August 6, 1822, as saying it had "published ... about thirteen years ago a copy of the original draft [of the Declaration] as it came from his [Jefferson's] own hands. This copy ... was found among the papers of Mr. Wythe, the friend and instructor of his early years. This copy was published in Niles's W. Register, & in various other newspapers of this continent." Hazelton (p. 602) was unable to locate it as published in the Richmond Enquirer and elsewhere about 1809.[40] In consequence, there has been doubt as to whether the copy in the New York Public Library (Document VII) or that in the Massachusetts Historical Society (Document IX) could be the Wythe copy. For the reasons given below, it is believed that the copy in the New York Public Library is, in all probability, the copy sent to Wythe.

Among the Jefferson Papers in the Library of Congress there is a box of newspaper clippings, one of which is taken from The Commonwealth (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) for July 1, 1807. This clipping is endorsed in Jefferson's hand: "Declaration of Independence" and the printing of the Declaration is prefaced by the following comment of The Commonwealth: "We have chosen to publish, at this time the original draught of the Declaration of Independence, as it came from the pen of Mr. Jefferson, found among the papers of the venerable George Wythe, after his decease, in the handwriting of the author. It will be seen, by a comparison with the Declaration, as adopted, that hardly any instrument of writing, of the same length, written by an individual, ever underwent fewer alterations and amendments, when submitted to an assembly for revision and adoption. It is evident, therefore, that Mr. Jefferson, at that time, expressed the sense of the nation at large—as he has ever since done—and, as we trust, he ever will do. The passages omitted in the original composition are printed in Italics." The italicized portions in The Commentator [sic][41] agree almost precisely with the corresponding underlined passages in the New York Public Library copy, and in one particular especially: in the Wythe copy "General" is omitted from the title of the Declaration and in the latter it is marked for omission. This occurs in no other copy except that made for Madison (and, of course, in the copy in Notes from which the Madison copy was made). In addition to this circumstantial evidence, it should be noted that the New York Public Library copy was acquired from Cassius F. Lee—who also possessed the two later drafts of Jefferson's ideas on a constitution for Virginia. Jefferson's proposed constitution was sent to Williamsburg by George Wythe. Could it be that the two drafts that belonged to Cassius F. Lee were those actually carried by Wythe? One of these drafts lacks the part that formed the Preamble to the Virginia Constitution: could it be that Wythe detached that part and presented it to the Virginia Convention? These, of course, are purely speculative questions, but the presence in Cassius F. Lee's hands of a copy of the Declaration bearing such exact relationship with the Wythe copy as printed in The Commentator [sic], together with his possession of two drafts of a document which Wythe transmitted for Jefferson, lends strong color of probability to the supposition that the New York Public Library copy is the George Wythe copy. The point is not conclusively established and so, in these pages, the copy in the New York Public Library is referred to as the Cassius F. Lee copy.

1950

Julian P. Boyd, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson

Boyd devotes a chapter in the first volume of Jefferson's papers to the composition, in June, 1776, of a proposed Virginia Constitution. His notes on Jefferson's manuscript second draft of the Virginia Constitution detail its provenance:[42]

Page 354

Dft (DLC).[43] This MS, which Ford labels "First Draft," was acquired by the Library of Congress in 1930, being donated by W. E. Benjamin of New York (Report of the Librarian of Congress, 1930, p. 64), who obtained it from Cassius F. Lee, Jr., of Alexandria, Va. The MS of the Third Draft, described below, and the Wythe copy of the Declaration of Independence were also at one time in the possession of Lee, (Boyd, Declaration of Independence, 1945, p. 39, 42, 43–5), from whom Ford obtained facsimiles of both the Second and Third Drafts (Ford, II, 7). However, some parts of the Second Draft became separated from the MS before it was acquired by the Library of Congress. These missing portions are noted below and the text is from Ford, II, 7. That part of the MS in DLC consists of eight pages and one tipped-in slip of paper. The present location of these missing parts is unknown. It is possible that Lee obtained the Second Draft, as he certainly did the Third, directly or indirectly from the papers of George Wythe. It is also most likely, as indicated in the notes to the Third Draft, that TJ sent more than one copy to the Virginia Convention. If so, this might explain the fact that the Second Draft became separated from the main corpus of Jefferson's papers. Ford (II, 7) noted that the Second Draft lacked the introductory part containing the justification for abolishing the "kingly office" and setting up new forms of government. As suggested above, in the

Page 355

notes to First Draft, it is very unlikely that such a preamble to the Second Draft ever existed (see footnote 1, below).

The supposition that TJ sent more than one copy of his proposed constitution to Virginia is possibly confirmed by the statements of William Wirt and B. W. Leigh. These statements have every appearance of being reliable: they were made independently, separated widely in time, and uttered by men of recognized probity, one of whom supported and the other of whom opposed Jeffersonian principles. Each flatly asserted that he had seen in the State archives at Richmond a draft of a proposed constitution of Virginia, in TJ's handwriting, that he had submitted to the Convention in 1776 (Wirt, Henry, I, 196; B. W. Leigh, Procs. and Debates of the Va. State Conv. of 1829–1830, Richmond, 1830, p. 160). Leigh added, in the statement he made in 1830, that the MS had "long since" disappeared from the council chamber.[44] It is known that the Third Draft of TJ's proposed constitution was found among George Wythe’s papers at his death in 1806 (see notes to Third Draft). Wythe must, therefore, have retained this text, even though it was the fair copy, correctly docketed by TJ as a bill ready to be introduced. In view of this and of the clear indications that the Third Draft was copied from another text than our Second Draft, Wirt and Leigh must have seen some other copy in the council chamber. If so, that copy, having disappeared before 1830, is not known to be in existence. It could not have been our Second Draft (see above and note 1, below).

- View this manuscript at the Library of Congress.

- Read this text on Founders Online, National Archives.

Boyd's notes on Jefferson's manuscript third draft of the Virginia Constitution argue that this is the copy transmitted to Williamsburg by Wythe, and found in Wythe's papers after his death in 1806:[45]

Page 364

Dft (NN).[46] This copy of TJ's constitution was folded and docketed in correct legislative form. At the top of the two sheets, after it was folded, TJ endorsed this title on his substantive law: "A Bill for new modelling the form of government, & for establishing the fundamental principles thereof in future." Below this, he added: "It is proposed that this bill, after correction by the Convention, shall be referred by them to the people to be assembled in their respective counties and that the suffrages of two thirds of the counties shall be requisite to establish it."

The provenance of this text is given in a memorandum of Victor H. Paltsits (Ford Papers, NN, 1 Feb. 1916): the document was acquired from Cassius F. Lee, Jr., of Alexandria, by "William Evarts Benjamin, then a well-known dealer of New York City who acted in the matter for some woman whose name is not revealed." Alexander Maitland purchased it of Benjamin for the Lenox Library. Shortly after this text was brought to light in 1890, efforts were made to identify it as the copy that TJ had given to George Wythe to convey to the Virginia Convention (D. R. Anderson, "Jefferson and the Va. Const.," Amer. Hist. Rev., XXI [1915-1916], 751). A close comparison of the copy found among Wythe's papers at his death in 1806 and printed with meticulous accuracy in the Richmond Enquirer, 20 June 1806, clearly establishes the identity of that copy and the one now in the New York Public Library, here designated as the Third Draft (Boyd, Declaration of Independence, 1945, p. 44-5). In 1825 TJ wrote: "I... drew a sketch or outline of a Constitution, with a preamble, which I sent to Mr. Pendleton, president of the convention.... He informed me afterwards by letter, that he received it on the day on which the Committee of the whole had reported to the House the plan they had agreed to..." (TJ to Augustus B. Woodward, 3 Apr. 1825). It has been assumed that this was a mistake of memory on TJ's part and that he confused Pendleton with Wythe (Hazelton, p. 451). Wythe reported to TJ that "the one you put into my hands was shewn [italics supplied]" to those chiefly engaged in framing the Constitution (Wythe to TJ, 27 July 1776). This, together with the significant fact that Wythe's copy remained among his papers, indicates that TJ was correct in saying he had sent a copy to Pendleton. If so, this would tend to confirm the supposition advanced in the notes to the Second Draft that two copies were sent. Wirt indicates that the copy he saw in the State archives was the one "forwarded... to Mr. Wythe";

Page 365

however, he also describes it as "an original rough draught," a description which scarcely fits the Wythe copy or Third Draft (Wirt, Henry, I, 196). Moreover, if Wythe's copy had been used by the Convention as the text from which several parts were taken for incorporation in the Constitution adopted by that body, it seems very likely that some corrections or markings on the MS of the text would have been made to indicate what parts had been selected, how they had been altered, s.c. (see Conv. Jour., May 1776, 1816 edn., p. 78, for 28 June, when it was ordered that "the said plan of government, together with the amendments, be fairly transcribed" [italics supplied]). No such alterations or markings appear on the Third Draft.

1 MS torn; text supplied from the precisely correct and literal text printed in the Richmond Enquirer, 20 June 1806.

2 A word must have been omitted by TJ at this point; elsewhere in the document the comparable phrase is employed: e.g., "incapable of holding any public pension...," not "incapable of any pension." The fact is that at this point in the Second Draft TJ wrote: "incapable of being again appointed to the same"; then struck out the words "being again appointed to"; then interlined "holding," making the phrase read as he usually wrote it "incapable of holding the same." However, the word "holding" appears also to have had a line drawn through it, though it also bears evidence of the slight smudge that TJ occasionally made in his rough drafts, as if he had run his finger over a freshly drawn line or word to expunge it. At all events, it is certain that "incapable of holding" is what he normally would have written and it is equally certain that "holding" was interlined though perhaps lined out. The point is worth noting since both the text of the Third Draft and the text of the Enquirer omit the word "holding" at this point, thus adding to the preponderant evidence that they are identical.

3 The square brackets here and below in the text are in the MS.

4 The words in italics were struck out, and then TJ interlined the following words at the top of the same page of MS: "nor shall there be power any where to pardon or to remit fines or punishments." This clause was finally inserted in the next to the last paragraph under "1. Legislative," above.

5 The six lines in the MS beginning with the words "by an act of the legislature" down to and including "defined by the legislature, and for" are written on a slip of paper pasted on the MS at this point. This represents a curious omission made by TJ in copying, an omission that seems inexplicable except on the ground that the Third Draft (Wythe's copy in NN) was copied not from the Second Draft (DLC) but from another text. As originally copied in the Third Draft, TJ caused this passage to read in part, without a break in the lines, "for breach of which they shall be remove able [end of line] the punishment of which the said legislature shall have previously prescribed certain and determinate pains...." The First Draft includes in rough, interlined form the six lines thus omitted at the end of the line "they shall be removeable," but in the Second Draft this passage comprises four and a half lines at the bottom of page 7 and two and a half lines at the top of page 8. It is conceivable that TJ could have accidentally skipped such a passage if it had ended at the bottom of a page or if its beginning and end coincided with the beginning and end of a line. But it is difficult to believe that he could have made this error if he had been copying from a text where the passage began in the middle of the line near the bottom of one page and ended in the middle of the line near the top of another, particularly in a case where the omission involved such a sharp break in the continuity and sense. The evidence in this instance alone is not conclusive, but taken in connection with TJ's remarks in 1825, with the statements of Wirt and Leigh as cited in notes to the Second Draft, and other evidences given in these notes, it seems certain that the Third Draft was copied from another fair copy made from the Second Draft. At all events, the omission of this passage conclusively proves that the Third Draft is the copy that George Wythe carried to Virginia, for the Richmond Enquirer printed the six lines written on the slip of paper, but neglected to include the lines written underneath. This typographical error obviously could have occurred only in the use of the copy now in NN, which, therefore, is the copy transmitted by Wythe.

- View this manuscript at the Library of Congress

- Read this text on Founders Online, National Archives.

1983

Kirtland, George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge,

Page 298

In an appendix to his 1983 doctoral dissertation,[47] Robert Bevier Kirtland summarizes the history — and probable ultimate disappearance — of George Wythe's papers:

APPENDIX A:

WHAT HAS BECOME OF GEORGE WYTHE'S PAPERS?It is intriguing but apparently idle to speculate on the possibility that a substantial corpus of Wythe papers may survive to the present day.

Wythe may not, in fact, have kept extensive files. Few men of his era shared Jefferson's conspicuous sense of the future and of their importance to it. It was Jefferson, indeed, who remarked to Tyler that he had been surprised to learn of the existence of Wythe's manuscript lecture notes, since "he might have destroyed them, as I expect he has done [to] a very great number of instructive arguments delivered at the bar, and often written at full length.1

Apart from small bequests and the establishment of a trust to provide for Lydia Broadnax, Wythe's entire estate went to the brother and two sisters of George Wythe Sweeney: Charles A., Ann, and Jane Sweeney. Charles and Jane were minors (Holder Hudgins of Mathews County, the ultimate purchaser of Chesterville, was their guardian) as late as November, 1808, and before that date (by which time she had married John Cary, and seems to have been living in Henrico County), Ann may have been under Hudgins's guardianship, too.2

1 Jefferson to John Tyler, 25 Nov. 1810, in answer to Tyler's letter cited above, Chapter I, note 9: DLC, Jefferson Papers, 191:34037.

2 The Wythe heirs and their guardian can be traced back, in part, through Abraham Warwick, who owned the Wythe Richmond homesite in the

Page 299

There is no evidence that these grandchildren of Wythe's sister, Ann, were living with their great-uncle, like their brother, George, at the time of Wythe's death. If they knew of his papers, they apparently had no interest in or appreciation of them. Governor Tyler suggests to Jefferson, in the letter cited above (Chapter I, note 9), that perhaps the latter was entitled to the manuscript of the lectures by reason of the bequest of Wythe's library (Would that Jefferson had overcome his scrupulous regard for the exact terms of the bequest! Had he, the manuscript might have survived. Jefferson's conscience in this regard is in stark contrast with the uncertainties of Tyler, who though a lawyer and later a judge could say, four years after Wythe's death, "You are entitled to [the manuscript] by his will (as I am informed)"!).

Moreover, there is in the executive papers of Virginia a letter written by Thomas Ritchie to Governor William H. Cabell, dated 27 April 1807, covering certain "valuable papers" that had come into the editor's possession through "Major Duvall (acting Executive of Mr. Wythe)" and were, at the latter's request, to be deposited in the State archives.3 There can be little question that these papers, otherwise undescribed, had come from Wythe's files. There is no trace of them today, nor was there when the archives were calendared at the end of the last century.

1850's; see Richmond City Hustings Deeds, Book 21, p. 570, and Book 31, p. 385; Henrico Court Order Book #16, p. 223: #14, p. 162; and Henrico Court Minute Book, 1823-1825, pp. 269, 279, all in Vi.[48]

For the information on Hudgins's purchase of Chesterville, I can cite only a newspaper article from the Daily Press of Newport News, Hampton, and Warwick, 31 May 1953, section D, p. 1, purporting to give the family tradition of Col. Robert Hudgins, a descendant of Holder and the last private owner of Chesterville; see Appendix B.

3 Calendar of Virginia State Papers, IX, 511.

Page 300

Probably these papers included the draft of Jefferson's proposed constitution for Virginia, which Ritchie said had been found in Wythe's "literary reliques" when he published it in the Enquirer; William Wirt and Benjamin Watkins Leigh saw such a document in the archives, said to have come from Wythe's papers, but it had disappeared by 1830. Julian P. Boyd has convincingly demonstrated that the copy of Jefferson's proposed constitution which entered the stream of commerce when sold in 1890 by Cassius F. Lee, Jr., of Alexandria, Virginia, and is now in the New York Public Library, is precisely the same used by Ritchie for his publication of it.4 Ritchie further says that he had then in hand a Jefferson autograph of the Declaration of Independence, for which, as for the first, he was "indebted to the politeness of Major Duval, the sole executor of the estate."5 It seems more than coincidental that the same M. Lee, at about the same time, also sold a Jefferson autograph of the Declaration.

Ritchie had also had, according to Tyler,6 the manuscript of the lectures delivered by Wythe, and had received that, too--the Governor supposed--from DuVal.

Ritchie was a petty but ambitious man, thirsting for a place in the sun of Virginia and national politics in the early nineteenth century. On the verge of bankruptcy throughout most of his life, he had also to live down the memory of a father, a Tappahannock merchant, who had barely escaped being tarred and feathered in 1766 for refusing to cooperate with resistance to the Stamp Act. W. E. Hemphill told me in the summer of 1969 that he thought it not beyond Ritchie to have kept

4 Boyd, V, 365, note 5.

5 Richmond Enquirer, 20 June 1806, pp. 2-3.

6 Loc. cit.

Page 301

and, in the course of political struggles in which there was a fad of appealing to the authority of "the Fathers," to have burned all the ... Wythe papers save the patently harmless ones.7

Certainly, the trail of the Wythe papers ends early, and with Thomas Ritchie; Hemphill added that he had long tried without success to trace them, or the memory of them, among the descendants of DuVal, who died at an advanced age in Buckingham County in 1842. The Ritchie Papers now at ViWC[49] contain only letters to Ritchie, and afford no hint of the Wythe files. Jefferson was unable to suggest any reliable source of information on Wythe to Sanderson in 1820.8

As for the Lee possession of Wythe documents like the Jefferson autographs--which would have been recognized as having an intrinsic value even before their author's death--a not entirely implausible series of links can be suggested. Ritchie's oldest child, Isabella Harminson Ritchie, married George Evelyn Harrison of Brandon (and outlived him by nearly sixty years, dying only in 1898). Ritchie delighted in Isabella's highly successful match and to the end of his life usually passed his holidays with her family at Lower Brandon. Brandon, on the south side of James River, forms a small and once closely-knit community with Westover, Berkeley, and Shirley on the north side. Shirley was the home of Anne Hill Carter, the second wife--a child bride--of Lighthorse Harry Lee, and so, the mother of the Confederate leader. One might speculate, given the extended family relationships maintained in the rural South, that the papers of Wythe, known to have come through DuVal to Ritchie, might have come with Ritchie to Brandon, and from Brandon

7 Conversation with the writer, Columbia, South Carolina, 9 July 1969.

8 Jefferson to John Sanderson, 31 August 1820; DLC, Jefferson Papers; 218:38932.

Page 302

into the possession of the Lees.

On the other hand, the documents once deposited in the State archives by Thomas Ritchie, whatever they may have been, may simply have been pilfered, as many others have been.

On Thomas Ritchie, Charles H. Ambler in 1913 published a highly apologetic biography: Thomas Ritchie: A Study in Virginia Politics (Richmond: Bell. Book and Stationery Company, 1913).

See also

- Declaration of Independence

- Etymological Praxis

- Jefferson-DuVal Correspondence

- Last Will and Testament

- Richmond Enquirer, 20 June 1806

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Last Will and Testament with Codicil, June 11, 1806, Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827, Library of Congress.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to William DuVal, 4 December 1806.

- ↑ Jefferson to Governor John Tyler, Sr., November 25, 1810.

- ↑ H.W. Flournoy, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers, vol. 9 (Richmond, VA: 1890), 511.

- ↑ Not to be confused with his father, Cassius F. Lee, Sr. (1808 – 1890), also a lawyer. Edmund Jennings Lee, Lee of Virginia, 1642-1892: Biographical and Genealogical Sketches of the Descendents of Colonel Richard Lee, (Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Co., 1895), 474.

- ↑ Wythe scholar Robert Bevier Kirtland suggests a possible family connection between the Ritchies and Lees.

- ↑ Lee, Lee of Virginia, 3.

- ↑ These sentiments are reiterated in a footnote to a letter Cassius Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis on July 18, 1888 (printed in Dunbar Rowland, Jefferson Davis, Constitutionalist [New York: J.J. Little & Ives, 1895], 10:76), asking if Davis might give him an original copy of a letter from his relative, Robert E. Lee:

Cassius Francis Lee, Jr. was born at Alexandria, Va., the 4th. day of January, 1844.

He was prominent in the civic, business and religious life of the city, and took a particular interest in all that pertained to the history of the old families of Virginia, collecting wills, deeds, letters, and all manner of genealogical data—Had his life been spared he would have arranged his papers for publication and would have edited a most admirable book.

He died Sept. 4th., 1892.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Augustus Elias Brevoort Woodward, 3 April 1825, Founders Online, National Archives; The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827, Library of Congress.

- ↑ Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 1, 1760-1776 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1950), 334; Richard Henry Lee to General Charles Lee, 29 June 1776. In James Curtis Ballagh, ed., The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, vol. 1, 1762-1778 (New York: Macmillan, 1911), 203.

- ↑ Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, 27 July 1776, The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827, Library of Congress.

- ↑ Paul L. Ford, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 2, 1776-1781 (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1893), 42; John H. Hazelton, The Declaration of Independence: Its History (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1906), 350-351.

- ↑ The Enquirer (Richmond, VA), June 20, 1806, 2-3.

- ↑ H.W. Flournoy, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, vol. 9, January 1, 1799 to December 31, 1807 (Richmond, VA: James E. Goode, 1890), 511.

- ↑ John Tyler, Sr., to Jefferson, 12 November 1810, Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827, Library of Congress. Jefferson, in his response of November 25, unfortunately declines to take possession of the manuscripts, and suggests only that they go back to Wythe's executor, Major Duval.

- ↑ "Declaration of Independence," Weekly Register 4, no. 18 (3 July 1813), 281-284.

- ↑ Hazelton, Declaration of Independence, 350-351.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Wythe, 16 September 1787, in The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1 General Correspondence 1651-1827, (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1974).

- ↑ "To Thomas Jefferson from William DuVal, 10 July 1824," Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Proceedings and Debates of the Virginia State Convention of 1829-1830 (Richmond, VA: Ritchie & Cook, 1830).

- ↑ John Page, Jr., to James E. Heath, 3 January 1834, in George Wythe, Etymological Praxis in Greek and Latin of Part of Homer's Iliad, Manuscripts Collection, Virginia Historical Society.

- ↑ Alexander H. Everett, "Patrick Henry," in The Library of American Biography, 2nd Ser., Vol. 1, edited by Jared Sparks (Boston: Little and Brown, 1848), 317.

- ↑ Magazine of the Society of the Lees of Virginia 1, no. 1 (December 1922).

- ↑ Technically, the American Philosophical Society.

- ↑ Worthington C. Ford, "Jefferson's Constitution for Virginia," Nation, August 7, 1890, 107-109.