"An Account and History of the Tazewell Family"

by Littleton Waller Tazewell

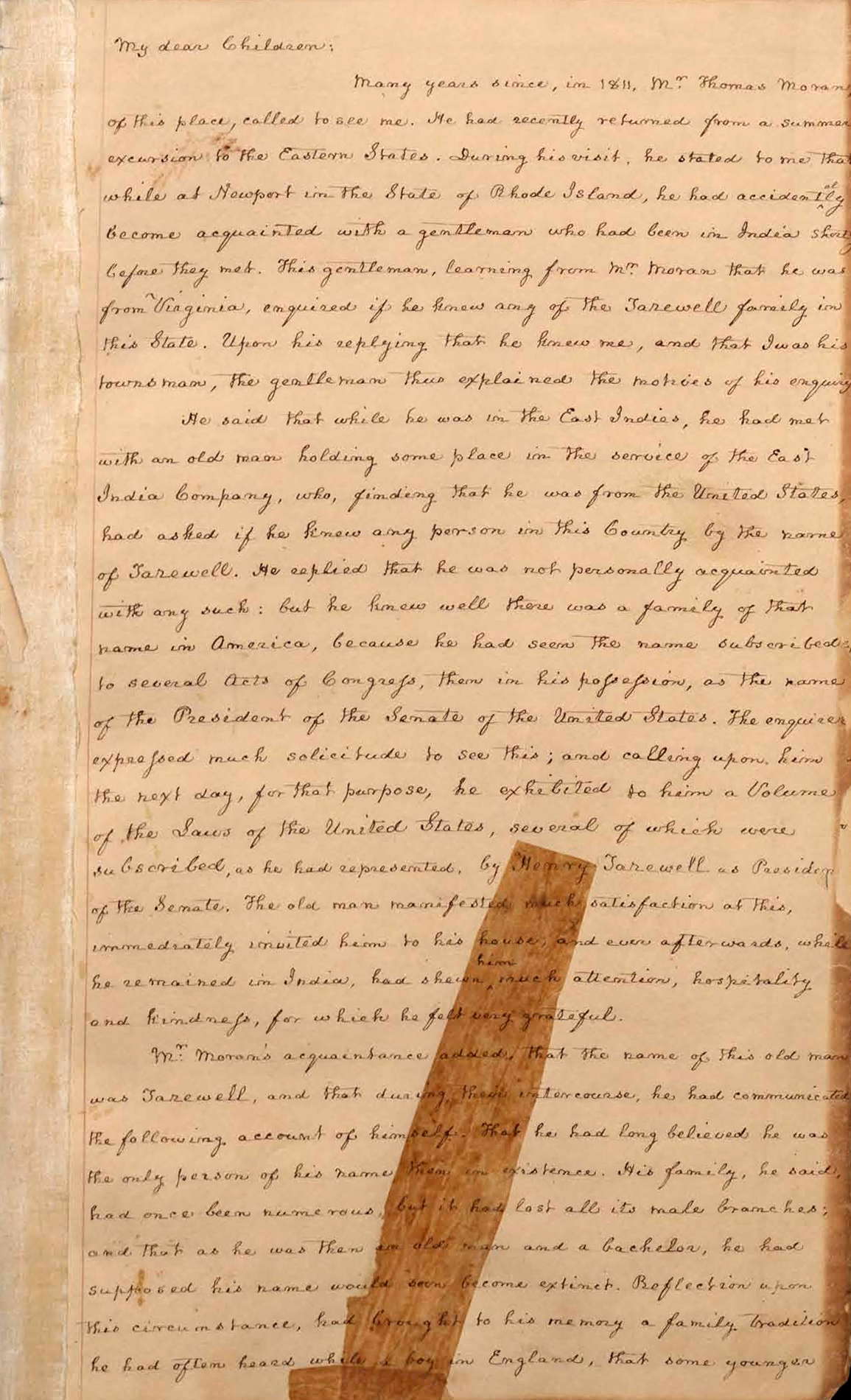

A manuscript volume written in 1823 by Littleton Waller Tazewell (1774 – 1860), "An Account and History of the Tazewell Family"[1] traces the lineage of the Tazewell family from their first ancestor who migrated to North America, Nathaniel Littleton, winding its way through his descendants, down to the author and his contemporaries. Tazewell addressed the work to his children, believing they might one day feel the "lively desire of knowing and of recording our ancestors".[2]

Tazewell was born in Williamsburg, Virginia. For three years, he was tutored by George Wythe in Greek, Latin, and mathematics, and in 1791 he graduated from the College of William & Mary. He studied law in Richmond under John Wickham (also a student of Wythe's), and was admitted to the bar in 1796 to practice in James City County. Tazewell became a career politician, serving in the Virginia House of Delegates, United States Congress, the Virginia General Assembly, and the U.S. Senate. He was Governor of Virginia from 1834 to 1836, and then retired. He died at his home in Norfolk, in 1860.

Tazewell's manuscript is a particularly rich, first-hand source for the life and habits of George Wythe. Tazewell's account describes Wythe's idiosyncratic methods of instruction; asking his pupil to translate Greek and Latin passages chosen at random from a book in his personal library. The history also provides a strong sense of Wythe as a person: we learn of Wythe's happy tears at being elected a Virginia representative for the Constitutional Convention in 1787, and his generosity in allowing Tazewell and other young men to board with him in his home. Tazewell notes with great affection Wythe's special fondness for teaching, and Wythe's unmatched reputation as a scholar.

Full text

- MS Word (MB)

Contents

- 1 Excerpts from An Account and History of the Tazewell Family, 1823

- 1.1 Page 70

- 1.2 Page 83

- 1.3 Page 95

- 1.4 Page 97

- 1.5 Page 98

- 1.6 Page 99

- 1.7 Page 102

- 1.7 Page 104

- 1.8 page 125

- 1.9 Page 126

- 1.10 Page 127

- 1.11 Page 128

- 1.12 Page 129

- 1.13 Page 130

- 1.14 Page 131

- 1.15 Page 132

- 1.16 Page 133

- 1.17 Page 134

- 1.18 Page 135

- 1.19 Page 136

- 2 See also

- 3 References

Excerpts from An Account and History of the Tazewell Family, 1823

Page 70

[John Tazewell]... finished his legal education [in Williamsburg], and having obtained a license, he commenced the practice of law in that vicinity. He attained eminence as a lawyer, and enjoyed the most lucrative practice of any one then at the bar, probably. At the commencement of the Revolution, John Tazewell succeeded Mr. Wythe as Clerk of the House of Burgesses.

Page 83

[Henry Tazewell's] ... licence [to practice law] was granted by John Randolph the Attorney General and by George Wythe esq: each of them filling a highplace at the bar for the old General Court, by which Court they had been appointed examiners, in pursuance of the Act of Assembly, upon the subject, then in force.

Page 95

[For Henry Tazewell] ... to have acquired and maintained such a rank as he held amongst such competitors and especially with such judges as Pendleton, Wythe, Blair, Lyons, and Waller, who then presided in these courts, is sufficient evidence of the legal acquirements of Henry Tazewell.

Page 97

[An old man named Charles Lewis, a freeholder, got up to speak at the York election, he said] ... that if the question who he should depute for him to decide unknown and foreseen matters, he would unquestionable vote for the persons to whom he addressed himself; for as to such subjects, their minds were as impartial as his own, and he had unlimited confidence (which experience had taught him was well merited) in their judgements [sic], when exercised with such impartiality. But as there was now a single and know proposition to be settled, which all concurred in considering, as the most important of any that had ever come before the people, since the question of Independence, he thought it wrong to prejudge such a question, when it had not been fully examined. Hence, he had made up his mind, to vote in favor of persons who as far as he knew formed no opinion as yet, who were still open to conviction and unpledged to support any side, and who should be well qualified to determine wisely, what they were prepared to examine impartially. These reflections had called to his recollection his two fellow citizens George Wythe, and John Blair; and he hoped his friends who ezcuse [sic] him, if upon this occasion he had directed the sheriff to record his vote in favor of these distinguished patriots, whose age and retirement by keeping them aloof from the warm conflict that had been

Page 98

carrying on, had them still to be impartial, and whose long experience, and well approved past services, while they gave assurance of their wisdom, also preferred strong claims to the gratitude of their county. Scarcely these words uttered by Lewis, when General nelson, springing from the bench, where he taken a seat advanced to him, and seizing him by the hand, thanked him in the warmest terms for what he had said and done; adding that though Mr Lewis had got the start of him in the support of Mr Wythe and Mr Blair, whose merit none knew better than himself. He therefore directed the sheriff to record his votes in favor of these gentlemen and soliciting all those who might have come to the Courthouse intending to vote for him, not to consider him a candidate, but to follow his example in support these persons. Mr Prentis soon followed General Nelson in this course, and Mr Wythe and Mr Blair were elected by unanimous vote. When the election was over, General Nelson addressing the people observed that as they had elected these gentlemen without their knowledge, it would be well to complete they had had so begun, and to secure the approbation of the persons elected, and their consent to serve. He therefore proposed, that they should proceed in a body from York to Williamsburg, and be themselves the bearers of their own request that the person elected would accept their appointments, this proposition was carried by acclamation; and General Nelson placing himself at the head of his fellow-citizens, they moved in procession to Williamsburg, where upon their arrival they ranged themselves quietly in front of Mr Wythe's house and deputing their as their spokesman, he presented himself in their behalf to the old man, and announced what had occurred. When General Nelson entered the room, I [L.W. Tazewell] was reciting a Greek lesson to Mr. Wythe, and never shall forget the countenances of these two great men upon this occasion. — that of General Nelson was lighted up with the satisfaction which the conscisness [sic] of having willing done a good deed never fails to inspire. His address was short and rapid, for his utterance was always quick. He remarked to Mr Wythe, that altho' he had no expected to have seen him at the election that day, yet he regretted that he had not been there, for he would have seen exemplified very strongly the truth of a sentiment the conviction of a sentiment, which his whole life had manifested sufficiently, that the people were their own best governors, "True to this maxim the freeholders of York county, have this day unanimously elected you sir as one of their representatives in the next Convention. And as

Page 99

they did this without consulting you, they have come themselves to state to you what they have done: and to solicit you to fulfil the trust they have thus sought to confer upon you[.] They are now at your door, and have deputed me to make this communication in their behalf." Mr Wythe who had arisen when General Nelson first entered the study, had listened to these words with that sort of impatient anxiety that is produced by the anticipation of hearing something interesting, but of what nature we cannot conjecture—So soon as the communication was ended however he exclaimed, "At my door sir;" and immediately quitting the study went to the front door. We all followed him, and when we joined him at the door, the loud shouts with which he had been received by the assembled multitude were still ringing. An hundred voices exclaimed at the same time, "Will you serve?"—We have elected you without your knowledge, will you serve us" — Mr Wythe was much agitated, every muscle of his face was in motion, and when the good old man standing on his steps, his bald head quite bare attempted to speak, tears flowed down his cheeks in copious steams, and he could utter incoherent sentences. —It was to me the most interesting scene I had ever witnessed and the swelling of my little heart was only relieved by a floor of tears also. —General Nelson, seeing Mr Wythe's agitation, promptly observed, "Mr dear Sir we prize you too highly to suffer you to expose yourself thus uncovered. Come into the house, and let me report your answer which I hope will accord with all our wishes." Mr Wythe however was still unable to say more than —"Surely" — "how can I refuse". "Yes I will do all my friends wish". Hearing which General Nelson immediately announced — "He will serve." And bowing to Mr Wythe left the house. — Again the shouts of the multitude made the welkin roar and they passed respectifully by the door toward's Mr Blair's. Mr Wythe remained bowing most gracefully to the throng as it moved by him, and when they left retired to his own apartment, and was seen no more that day.

Page 102

In October 1788 a new organization of the judicial establishment of Virginia was created of three judges, Pendleton, Wythe and Blair. — The general Court was composed of five judges only, Carrington, Fleming, Lyons, Mercer and Tazewell — And the Court of Admiralty three Cary, Henry and Tyler. — These eleven judges constituted the Supreme Court of Appeals, in which none of the judges sat on the examinations of the decision of their own court. The adoption of the new Federal Constitution, by transferring all admiralty to the United States, would when this government went into operation, necessarily extinguish the state court of admiralty. A new arrangement therefore of the Court of Appeals was indispensable. A scheme of Courts of assize had been adopted in 1786, but had been postponed from time to time its execution. As the project however required the agency of all the eleven judges of the Court of Appeals, whose numbers would be reduced to eight by the extinction of the Court of Admiralty, the modification of that scheme became also requisit [sic]. In this state of things the Assembly repealed the law establishing Courts of Assize, and passed the various acts altering the Court of Appeals, and General Court and creating District Courts. Under the new system, the Court of Appeals was made a direct Court and give judges were appointed to this Court exclusively The High Court of Chancery remained as before but was to be held by a single judge only. The state was divided into five different Circuits each containing four districts and two judges of the general court was assigned to each Circuit, in all the districts of which courts were to be held by two judges, on certain appointed days twice in each year.

In the designation of the Judges of these different courts Mr. Pendleton and Mr. Blair were taken from the Court of Chancery, Mr. Carrington, Mr. Lyons, and Mr. Fleming, the senior judges of the General Court were taken from that court and these five were made judges of the new Court of Appeals. — Mr. Wythe the other judge of the Court of Chancery, preferred remaining in that Court, and was therefore made the sole Chancellor.

Page 104

While a member of the house of delegates in 1785 [Henry Tazewell] was placed on the bench of the old general Court, of any reputation there who was ever made a judge, and the last judge of that court ever appointed. When the present General Court was created, in 1785, he was the second judge on its bench, and by the death of Judge Mercer very soon became its chief justice. And when in 1793 he was translated to the bench of the Court of Appeals, he was the last judge of the old general court, who was so transferred. Upon to this period the Assembly had always filled the bench of the Court of Appeals, by translating hither the senior Judges of other courts. No departure from this rule ever occurred except in the case of Mr. Wythe, who did not wish to quit his own court.

Page 125

I will mention a circumstance that occurred about this time [c. 1785], which most probably had some effect much influence upon my future destiny. To give more celebrity to his establishment [Mr. Maury's grammar school in Williamsburg], it was a custom with Mr. Maury to have occasional public examinations of his scholars. These examinations were generally made by, and always in the presence of, the visitors, governors, and proffessors [sic] of William and Marry college [sic], and any other distinguished gentlemen, who happened to be in Williamsburg at that time. Upon one of these occasions it fell to the lot of my class to be examined by the venerable and learned chancellor the late George Wythe. We had just begun the lives of Cornelius Nepos, and placing myself at the head of my class fellows, I led them up to his chair, to recite their lesson from this work. — The recitation being finished, Mr. Wythe questioned us very particularly in passing and as to the subject matter of the life, a part of which we had just read. — It was the life of Eumenes. To ail his questions put to me I answered with a promptness, and accuracy which obviously pleased him very much; and I manifested such a perfect acquaintance with the portion of Grecian history connected with this biographical sketch, as to excite even his astonishment, for I had not then attained my tenth year. When the examinations were ended, he called me to him and the in the presence of my tutor and all the other gentlemen, extolled my exhibition in such flattering terms, that was afterwards distinguished in the school, as one of its principal ornaments. — Some months after this, returning from school one evening to my grandfather, I found him sitting with Mr. Wythe. They had been very intimate in their early days; and altho' my grandfather never went out then and Mr. Wythe very rarely, yet he made it a point to call to see my grandfather once or twice every year, and to spend an afternoon with. When I came in Mr. Wythe very immediately recognized me, and seeing my grandfather caress me as he did, re repeated to him with high eulogies the occurrences of my examination. Pleased to hear this account (which I had before told him from Mr. Wythe himself, my grandfather requested him to examine me again; and he did so. I was then reading Caesar's Commentaries, and Mr. Wythe taking the book from me, made me recite several passages and to accompany my recitation with an account of the circumstances introductory to the passages read. To these my grandfather added many questions relating to this portion of the Roman history and to ancient Geography of the Roman Empire at that time. I answered all the questions, and performed all that was required of me so entirely to Mr. Wythe's satisfaction, that he

Page 126

observed to my grandfather with an appearance of great earnestness "Mr. Waller this is a very clever boy, and when he has advanced a little further, you must let me have him." To this the good old man replied with much feeling "George (for by this familiar appellation he always spoke to Mr. Wythe) this boy is sole companion of my old age and the principal comfort, I feel that I cannot part with him while I live, but when I die, if you will take him under your charge, I shall consider it as the greatest and highest favour you can confer on each of us." Mr. Wythe thereupon promptly answered that he would do so; and the conversation between the old gentlemen was turned to other subjects. I was too young then in 1785— to think of what was to happen to me thereafter.

Page 127

Mr. Maury removed from Williamsburg, having entered into holy

Page 128

orders, in the summer of 1786, and after his removal I was left entirely to myself, to do as I pleased, for my father was often from home, and while there was too actively employed to attend much to me. Altho' not visious, yet I became very idle and scarely ever opened a book. I continued thus for some months, when day meeting Mr. Wythe in the street, he immediately accosted me, and carried me to his house. There he questioned me very closely as to my situation and occupation, and examined very closely as to my studies. He made me translate for him an ode of Horace and some lines in Homer. I did not acquit myself as well as I had formerly done, but he seemed satisfied with my performance, which was without any previous preparation. My father was then in Richmond, but the day after his return Mr. Wythe called to see him, and stating to him what had passed between my grandfather and himself some time before, and what had taken place between him and myself during my fathers absence, he very kindly offered to take me under his charge. My father was delighted at this unexpected overture, to which he very willingly assented and the very next day I was sent to attend Mr. Wythe who resided but a short distance from our house.

Before I proceed to give any further account of myself, let me make you somewhat acquainted with this great and good man, under whose tuition I passed several of the succeeding years of my life. Mr. Wythe was a native of the county of Elizabeth-City. I have often heard him say that we was intirely indebted to his mother for his early education. She was an extraordinary wom[an] in some respects, and having added to her other acquirements a knowledge of the Latin language, she was the sole instructress of her son in this also. He was very studious and industrious, and as he grew up, so much improved on this good foundation his mother had laid, that he made himself in time one of the best Latin scholars in America. Long after he had attained manhood, and had been engaged extensively in the practice of the law, he determined to teach himself Greek and he entered upon and prosecuted this task with so much zeal, that in a few years he had made himself certainly the very best Greek scholar I have seen and such was universally acknowledged to be. He afterwards in like manner acquired the French language, and became deeply versed in Algebra, Mathematics,

Page 129

and Natural Philosophy. He therefore may [be] very properly considered as one of the rare examples the world has ever produced of a man who by his own unaided efforts, has made himself a profound scholar. When he came to Williamsburg, and commenced the study of the law, under the direction of my grandfather Waller, who was ten years older than himself, and engaged at that time in its practice, Mr. Wythe by his unwearied industry, soon acquired a very extensive knowledge of this science, in all its branches, and obtaining a licence, returned to his native county, where he commenced the practice of the law about the year 1748. He was then elected a member of the house of Burgess, and continued to represent the County of Elizabeth City in that body for many successive years.

Very soon after he commenced the practice of the law, he acquired so much distinction in his profession, that he relinquished it in the inferior courts, and took his stand at the bar of the General Court, where all the eminent Counsellors of Virginia were then collected. At this bar, his indefatigable industry, extensive knowledge, and profound research, speedily acquired for him very high and well merited distinction; and he ascended to its highest rank, in which he found no other equal competitor, than the late venerated Edmund Pendleton, who was his senior by some years.

It would be odious to draw a comparison between these two great men, both of whom stood so high and deserved so much. Honourable rivals for public distinction during many years, they were unlike in so many respects that no fair parallel could be drawn between them. The address of Mr. Pendleton was most popular, and his manners more courtly than those of Mr. Wythe, whose fondness for study kept him much secluded from general observation, and whose excessive modesty concealed much of his merit even in this respect. For the manners of Mr. Wythe were very polished indeed, and full of dignity and grace. Mixing much more with the world, and more conversant with men than Mr. Wythe, Mr. Pendleton looked always to consequences. He therefore rarely made an enemy, but acquired the esteem of a very large circle of friends, who always sustained and supported him, and who he in like manner upheld. While the stern integrity and unyielding firmness of Mr. Wythe's character, carried him always straight to his object, so soon as he was convinced it was proper and

Page 130

in the pursuit of what he thought right, he was heedless and utterly indifferent to after affects. This strong differences between the two was exemplified in their conduct and practice both at the bar and in the Assembly. Mr. Wythe would never engage in a cause which he thought wrong, and would often abandon his cases when he discovered that they had not been fully represented to him; which Mr. P— [Pendleton], considering the subject more correctly, felt no scruple in exa[c]ting his professional powers for any client when he had undertaken to represent, or in taking any cause which presented to him. In the year 1766 when the enormous fraud committed by Speaker Robinson was detected, Mr. Pendleton whose patron and personal friend the Speaker was exerted his every power to ward off the blow which threatened him; but yet so conducted himself throughout the enquiry, that he was finally represented as one of its authors. If this had been Mr. Wythe's situation, no consideration would have prevailed upon him to refrain from denouncing his very best friend, and from prosecuting him so far as his delinquency required.From these different traits in their characters, it may readily [be] inferred, that Mr. Pendleton was the more successful practitioner, although Mr. Wythe was considered as the better lawyer. And the former acquired with ease but retained with effort the high distinction to which he afterwards rose. When the Revolution came on they were both sound whigs, but they seem to have differed in this too as in most other respects; Mr. Pendleton yielding to the force of public opinion, and thus enabled in some degree to direct, what he could not control. He very ably assisted in effecting the Revolution in government, but strongly opposed, and to his efforts Virginia is strongly indebted for the prevention thus of much revolution in society. Mr. Wythe on the contrary having once satisfied himself of the rights of the colonists, and of the usurpations of the mother country, labored with all his soil to stimulate and prepare the public mind for a change, and not believing that a revolution in government could ever be perfectly achieved, unless a great change in society was previously effected, he would have gone all length in uprooting the basis upon which society itself rested, rather than hazard the success of the scheme, he deemed so essential to the liberty of the people. While Mr. Pendleton calmly presided as chief of the Executive in the Committee of safety,

Page 131

Mr. Wythe altho' an old man, presented himself in his hunting shirt to Col. Innis proposing to enter the ranks of his detachment as a volunteer to fight the invading enemy. While the former yielded a reluctant assent to the policy which dictated a change in the system of entails then existing in the country, the latter was desirous to alter even the language of its people.

Both these great men pursued the same course, and successively filled almost every station of high distinction in the country. Mr. Pendleton was elected by the Convention (of which he was a member) to be one of the delegates in the first Congress, that assembled in Philadelphia in Sept. 1774. Upon the death of Mr. Randolph during the next year who had long presided both in the Assembly and Convention, the latter body then assembled in Richmond, chose Mr. Pendleton as their President and appointed Mr. Wythe to succeed him in Congress. In this situation he had a great share in preparing the declaration in independence, the production of his pupil and colleague Mr. Jefferson. When the new Government of Virginia went into operation in 1776, and the dissolution of the old government took place, a complete revision and re modification of all the statutes became necessary for this important duty Mr. Jefferson, Mr. Pendleton and Mr. Wythe were selected by the Assembly. — The execution of this important task making it necessary for Mr. Wythe to relinquish his situation in Congress, and Mr. Pendleton having then retired from the Assembly, in 1777 Mr. Wythe was elected to succeed him as the Speaker of that body. And as soon as a new judiciary was created by the Legislature in the winter of 1777, Mr. Pendleton, Mr. Wythe, and Mr. Nicholas, were made Judges of the Court of Chancery. While occupying this situation in the year 1786 Mr. Wythe was chosen by the Assembly one of the deputation from Virginia to the Convention, which the next year set in Philadelphia, and then formed the present constitution of the United States. He attended this Convention when it first met, but the illness of his first wife during its session compelled him to return home, so that he was not present at its adoption by that body. Both Mr. Pendleton and himself however were elected member of the Virginia convention to whom this Constitution was submitted afterwards for ratification and each of them ably supported its adoption by this State. Mr. Pendleton was elected the President of this body, and Mr. Wythe presided over its deliberations, as Chairman

Page 132

of the Committee of the whole. When the Courts reorganized in 1788 Mr. Pendleton was made the chief Justice of the Court of Appeals and Mr. Wythe declining and appointment to that Court was made the sole chancellor of Virginia, in which situation he died about the year 1805. His death it was generally believed, was produced by poison, administered in his coffee, by a reprobate boy, relation of his, who he undertaken to educate, and who afterwards convicted of having committed many forgeries of cheques in his patrons name.

Amongst many singularities in Mr. Wythe's character, all of which were results of his pure philanthropy, the most remarkable was his passion (for it really deserved that name) in the instructing and aiding in the education of youth. The difficulties and embarrassments he had experienced in educating himself, if I may so say, made him not merely willing but desirous to smooth the path and assist the efforts of others in this pursuit. Mr. Jefferson was greatly indebted for the aid he rendered in improving and forming his mind; and there was no period of his life I believe after he attained to manhood, during which he did not surer intend the education of several young men. For this he would receive no compensation, and could expect no satisfaction but that springing from the consciousness of performing a good action. Wherever he saw a youth of any promise, who had made some progress in his studies, he was desirous to have him, to the end he might stimulate to greater exertion and enable him to reach a higher eminence than without this aid such a one would ever rise.

This disposition will explain the conversation he had with my grandfather relative to me in the year 1785, which I have formerly stated. Let me now return to my story.

In the autumn of 1786, I was placed as I have stated under the guidance of Mr. Wythe. I lived with my father, but attended Mr. Wythe daily; I was the youngest boy he had ever undertaken to instruct, and had no companion in my studies with him at that time. His mode of instruction was singular: and as everything connected with the life and opinions of this great and good man must be interesting, I will here describe it. I attended him

Page 133

every morning very early, and always found him waiting for me in his study by sunrise. When I entered the room, he immediately took from his well stored library some Greek book, to which any accidental circumstances first directed his attention. This was opened at random, and I was bid to recite the first passage that caught his eye. Although utterly unprepared for such a task, I was never permitted to have the assistance of a Lexicon or a grammar but whenever I was at a loss, he gave me the meaning of the word or structure of the sentence which had puzzled me, taking occasion to remark to me the particular structure of the language, the peculiarity of its syntax, or the diversities of its dialects. Whenever in the course of our reading any reference was made to the ancient manners, customs, laws, superstitions or history, of the Greeks, he asked me to explain the allusion, and when I failed to do so satisfactorily, (as was often the case,) he immediately gave a full clear and complete account of the subject to which reference was so made. Having done so, I was bidden to remind him of it the next day, in order that we might then learn from some better source, whether his explanation was correct or not; and the difficulties I met with on one day, generally produced the subject of the lesson of the next. — This exercise continued until breakfast time, when I left him and returned home. — I returned again about noon, and always found him in his study as before. He then took some Latin author, and continued our Latin studies, in the manner I have above described as to the Greek, until about two o'clock when I again went home. In the afternoon I again came back about four o'clock when we amused ourselves until dark with working Algebraic equations, or demonstrating Mathematical problems. — Our text books in both cases were in the French language to which resort was had that I might perfect myself in this language also while I was advancing in the studies whose subjects were so comm[on].[3]

These evening occupations were occasionally varied, by employing me in reading to him detached parts of the best English authors either in verse or prose; and sometimes the periodical publications of the day — and whenever these last were the subjects of our employment, my reading was often interrupted by some anecdote suggested by the matter read, referring to minor events, in the history of the country or the character of those who had formerly occupied a distinguished situation in it. Of such anecdotes the long life and particular situation of Mr. Wythe had supplied him with a stock almost

Page 134

in exhaustible, which he told in a manner calculated to excite much interest. This mode of instruction would have been a very good one if I had been older or somewhat more advanced that I then was, but in my situation it was objectionable in many respects. The difficulties I encountered were removed with so little effort on my part, that having no occasion for the exercise of my own strength of mind it did not increase as much as would probably have been the case, nor did my instruction take such deep root as if I had been made to exert my own powers more. The subjects of our studies were also often times beyond the comprehension of one so young as I then was (for I was only twelve years of age) and therefore did not excite my attention sufficiently — and the irregular course of our reading, was not well calculated to enable me to require much useful knowledge of the language, altho' it gave me some instruction as to the subjects treated by the authors read. — By the help of a very at[t]entive memory however, I acquired a great deal and some very useful knowledge during this period of my life, the stock of which, the disposition I felt would I think much enlarged, provided by course of study had been more methodical and regular. But Mr. Wythe judged of me by himself I suppose, and therefore decided erroneously. He was a man however naturally endowed with great strength of mind, whose powers he had never called into exertion in this mode, until they were fully matured and ripened, whilst I was a boy of tender years whose intellect was just forming. In the mode I have just described passed away the first year I studied with Mr. Wythe. In the autumn of next year 1787 my father having purchased Kingsmill, and being about to remove there, and Mr. Wythe having lost his wife about this time, he proposed to my father that I should board with him. — This proposition was readily assented to by my father, and upon his removal from Williamsburg, I became an inmate of Mr. Wythe's house. My course of study was the same as before, but having now the free use of his library at all times, and knowing generally what would be the subjects of our exercises the following day, I was enabled to prepare myself for them better that I had done before. And when I was disappointed in this calculation, I rarely found any difficulty in playing off upon him some little stratagem or other, by means of which, the authors and passages

Page 135

I had already examined the preceding day became the selected books for our next days reading. This previous preparation, and the benefitted I derived from uninterrupted intercourse with my venerable tutor and from his instructive conversation made my progress and improvement much more rapid than it had ever been. I now became a great favorite of my much respected master, and he proudly exhibited me at all times as a boy of great promise. Every foreigner or other gentleman of distinction who passed though Williamsburg, generally made it a point to pay their respects to this distinguished man, and very few of these were ever suffered to leave his house, without being made to witness some of my performances. And when this arrived, most of our leisure moments were employed in making philosophical experiments, and ascertaining the causes of the effects produced. Several other young gentlemen were also taken by him as boarders, from whose society I likewise derived some information. So that this year passed away with me more profitably than even the preceding.

The experience of the year taught Mr. Wythe, what almost any other man than himself would have foreseen, that at his time of life in his situation, and with his habits, the presence of a numerous family about him, just occasion much more trouble than he could sustain. The necessary domestic duties occupied so much of his time, broke in upon his pursuits, and interrupted even his business and amusements. He was irritated and vexed by a thousand little occurrences he had never foreseen, and which any other would have guarded against. He could not bear and ought never to have subjected himself to any such burdens; He therefore very properly decided to apply the only remedy, which was to break up his boarding establishment, and to live by himself. He could not forego the pleasure he derived from instructing others however; and in refusing to take any young gentlemen to live in his house he still suppressed a wish however to continue his instruction to any such as would attend him for that purpose. Most of those who lived at a distance, did not so afterwards, but I continued to attend him as I had done. So soon as I left the house of Mr. Wythe my father placed me with our friend Mr. John Wickham. I have mentioned this gentleman before. When hostilities ceased with

Page 136

Great Britain in 1782, he left Mr. Fanning in Greenville, and returned to New York. From thence he proceeded to Europe, and having travelled there awhile, came back to the United States, and visiting Virginia about the beginning of this year 1786, he then determined to study the law and to practice there. He accordingly commenced the study of the law under the direction of my father, and obtaining a licence, entered into the practice and fixed himself in Williamsburg, where he kept a bachelor's house, at the time I am now speaking of the autumn of 1778. I then went to live with him, and as he did not dine at home, I dined out, first at Judge Prentis's, and afterwards with an old man by the name of Taliaferro, who resided near Mr. Wythe who I continued to attend regularly as I had done previously. Deprived now of the use of Mr. Wythe's valuable library for my preparatory studies, and losing much of the benefit I had derived from perpetual association with him, my improvement in some respects, was certainly not equal to what it had been during the last year; but I derived full compensation for this probably; in the society of my friend Mr. Wickham, and from my intercourse with two young gentlemen of Petersburg, who now became scholars of Mr. Wythe also, and boarded near me.

Early in the year 1789 the re-organization of the Courts, which had then recently been effected by imposing upon Mr. Wythe exclusively, the whole duties of the Chancery court made it necessary for him to remove to Richmond where his court was held. He therefore broke up his establishment in Williamsburg and fixed himself in Richmond, where he continued to reside until his death. When Mr. Wythe left Williamsburg, my father and Mr. Wickham concurring in the opinion that I was now sufficiently advanced to be placed at College, I was immediately entered a student of William and Mary — I continued to live with Mr. Wickham as before, but attended all the Professor's daily.

See also

- Caii Julii Caesaris et A. Hirtii de Rebus a Caesare Gestis Commentarii

- Cornelii Nepotis Excellentium Imperatorum Vitae et Editione Oxoniensi Fideliter Expressae

- Cours de Mathematiques

- Wythe the Teacher

References

- ↑ Littleton Waller Tazewell, An Account and History of the Tazewell Family (1823), Mss. MsV Ad1, Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, "Memoirs of My Life and Writings," in Vol. 1, Miscellaneous Works of Edward Gibbon, Esquire, with Memoirs of His Life and Writing, Composed by Himself: Illustrated from His Letters, with Occasional Notes and Narrative by John Lord Sheffield (London: Strahan and Cadell, and Davies, 1796), 2.

- ↑ We know of at least one mathematical treatise which Wythe owned in French: Etienne Bézout's Cours de Mathematiques (1781).