Tēs tou Homērou Iliados, Tēs tou Homērou Odysseias

by Homer

Των του Ομηρου Σεσωμενων Απαντων ΤομοιΤεσσαρες, Της του Όμήρου Ίλιάδος ό τόμος πρότρος Δεγτερος

The Iliad and The Odyssey

Little is known about the life of Homer. Even in Greek antiquity, no one knew anything for certain about the poet responsible for the Iliad and the Odyssey. Herodotus claimed he lived around 850BCE, while modern scholars usually date his poems to the second half of the eighth century BCE.[1] The Trojan War is estimated to have occurred at the end of the Mycenaean Age in Greece, around 1200BCE, meaning that Homer was looking back over 400 years to a heroic world much greater (in his esteem) than the contemporary world. Homer had to rely on a combination of evidence from the oral tradition in order to compose his poems, which provides some of the basis for the “separatist” view that the two epic poems were not written by the same person or perhaps were not written by just one poet at all but a combination of poets. It still cannot be proven whether both poems were written by the same person (scholars have spent entire careers trying to prove their view), but it is generally accepted that each poem can be attributed to a single person, whether that poet is one in the same or not. Regardless, the mixed dialect of Ionian Greek that each poem is originally written in indicates that both poems were written in the east Aegean. This is supported by contextual clues in the poems themselves. The two most plausible locations for the birth of Homer are Smyrna and Chios, but ancient Greeks viewed the poet as a blind minstrel wandering while he composed his epic poems which were sung or chanted to an accompaniment by the poet on a lyre. One can see from this, the similarity between the wanderings of Odysseus and Homer.[2]

Homer’s Iliad is an epic poem of a heroic or tragic nature, consisting of 24 books, all of which are original except for Book Ten which was likely added later.[3] The story of the Iliad is ripe with moral themes as it tells the tale of the wrath of Achilles during the last year of the ten-year Trojan War. The war began when Agamemnon led a unified force of Greek warriors across the Aegean Sea to attack Troy under the pretense of rescuing his brother Menelaus’s wife Helen from the Trojan prince Paris. Homer begins his narration in the tenth year of the war, actually covering only several weeks of the war focused on the anger of the great warrior Achilles at not being appropriately respected and honored by Menelaus. Significantly described in the Iliad are the deaths of Patroclus (Achilles’ foster brother and alleged lover) and subsequent vengeance killing of Hector (the oldest son of King Priam of Troy). The respect and compassion seen between the supposed enemies Achilles and Priam when the former returns Hector’s body is a clear example of the rules of war and humanity Greeks expected to be shown to one another. The story ends with the funeral of Hector (for which Achilles gave Priam a ten day break from battle, much to the anger of Menelaus). Homer does not address the death of Achilles, the Trojan Horse or the fall of Troy. All of those stories come to us from the Latin poet Virgil’s epic the Aeneid.

Homer’s Odyssey is an epic poem consisting of 24 books telling the story of the Trojan War hero Odysseus’s ten year journey trying to get home to his wife Penelope and son Telemachus in Ithaca, where he is king. This epic is distinct from the Iliad for, even though it refers to a Trojan War character, it is a more romantic rather than heroic/tragic poem. It is very clear in the Odyssey who the “good” and “bad” characters are, and therefore who the readers (or more accurately as it was intended to be recited orally, the listeners) should be rooting for. Odysseus is shown through much of Greek mythological writing as an intelligent and crafty individual: first tricking Achilles into agreeing to join the Greeks against the Trojans and secondly tricking the Trojans with the giant wooden horse which ended the war. In the Odyssey, Odysseus’s familial devotion, general intelligence, and his “eternal human quality[y] of resolution” contrast with the barbaric creatures he meets on his adventures, as well as with the suitors attempting to woo his wife.[4] Odysseus’s supreme human qualities served as an example to Greek men of idyllic behavior, just as Penelope’s devotion to her husband and home showed Greek women how to behave. Furthermore, these two characters were used throughout European literature to exemplify ideal behavior. The strong moral themes through the Odyssey in no way take away from the exciting adventures Odysseus encountered from the Cyclopes to the Lotus Eaters to the Sirens to tricking and slaughtering his wife’s suitors.

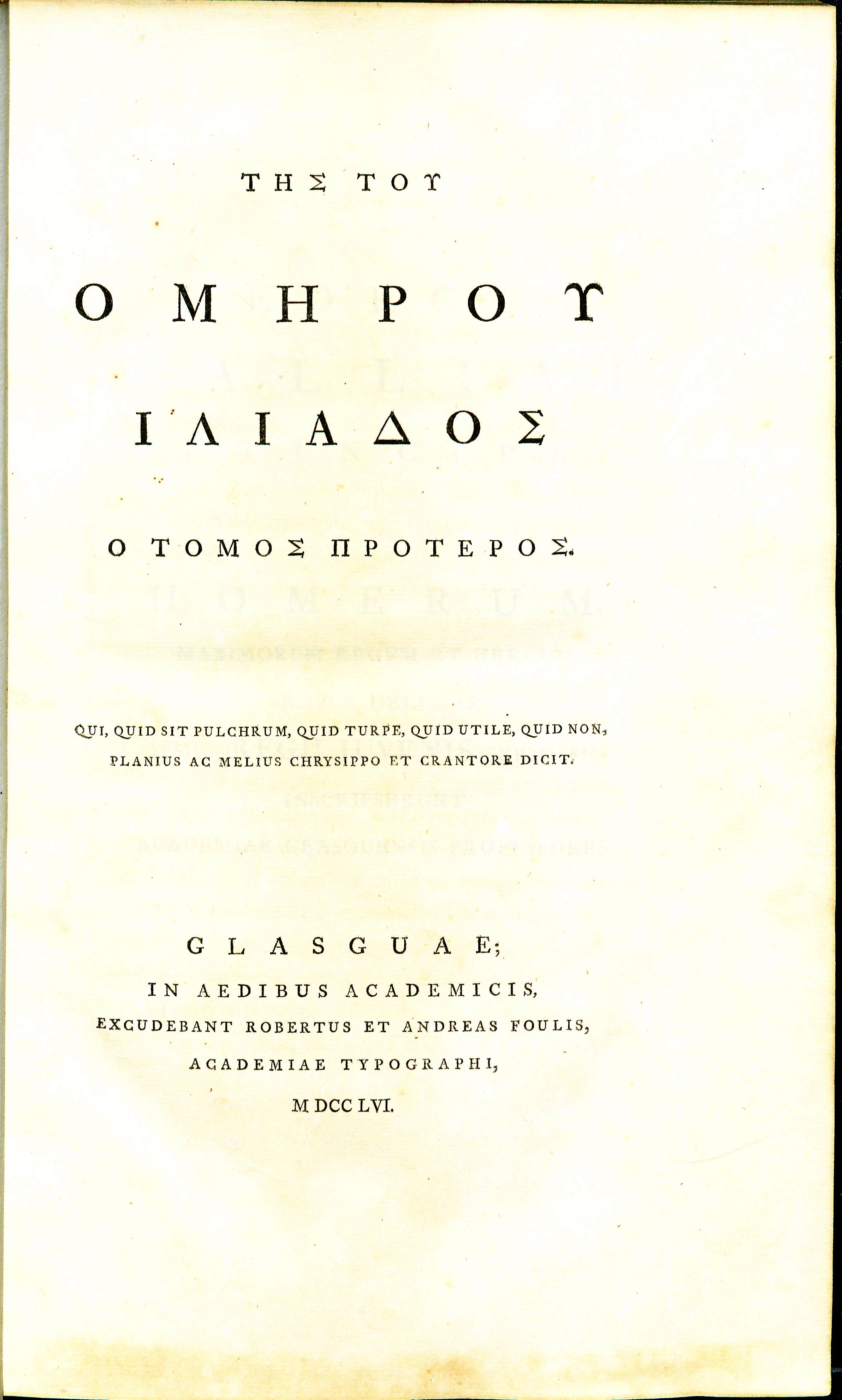

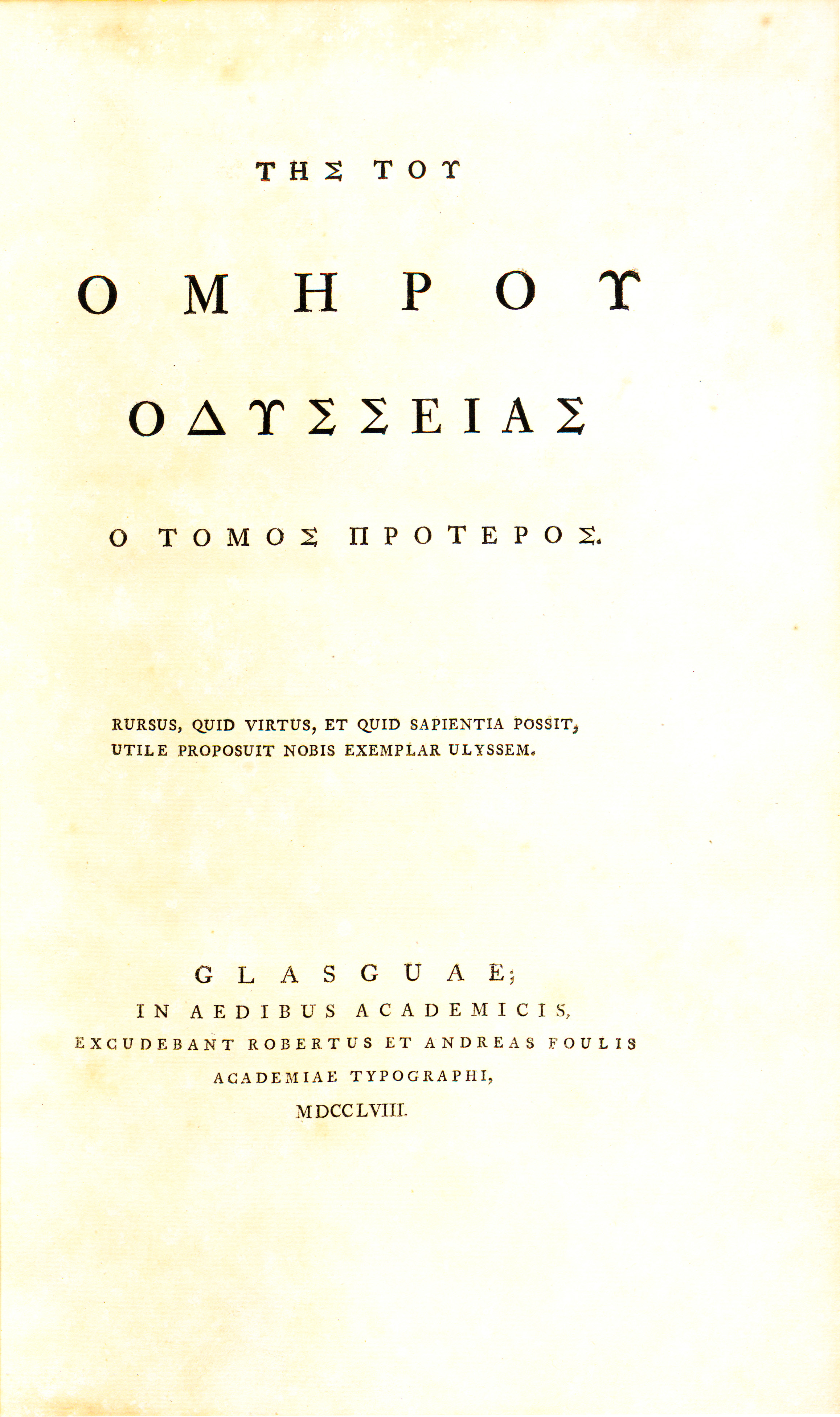

This two-volume set of Homer's epic poems was published by two well-known and regarded Scottish publishers. Robert and Andrew Foulis (ne Faulls) were brothers who opened their own publishing company and printing press in 18th century Glasgow.[5] Robert was a barber before enrolling in University of Glasgow courses, while Andrew “received a more regular education…[as] a student of Humanity” who taught Greek, Latin and French for a time after he graduated.[6] The brothers began as booksellers and then transitioned to publishing and printing books, with Robert initiating each endeavor before later being joined by Andrew.[7] In 1740-42, Robert had other printers print what he chose to publish, but began printing his own books in 1742 which continued until his and his brother’s deaths in 1775 and 1776, respectively, when Andrew’s son Andrew took over The Foulis Press.[8] The Foulis Press primarily produced text books and other “works of learning…and of general literature,” as it was the printer to the University of Glasgow.[9] The press is unique for the plethora of variant issues and editions of published books on special paper, in special font, or even on copper plates.[10]

Homer "One of the most splendid editions of Homer ever delivered to the world."

Bibliographic Information

Author: Homer

Title: Tēs tou Homērou Iliados, Tēs tou Homērou Odysseias.

Published: Glasguae: In aedibus Academicis, Excudebant R. et A. Foulis, 1756-1758.

Editors: J. Moor and G. Muirhead.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as Homeri Ilias. Gr. 2.v. fol. Foulis and [Homeri] Odysseus. Gr. 2.v. fol. Foulis given by Thomas Jefferson to Dabney Carr. Both the Brown Bibliography[11] and George Wythe's Library[12] on LibraryThing list the 1756 edition of the Iliad and the 1758 of the Odyssey as the ones intended by Jefferson's entries.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

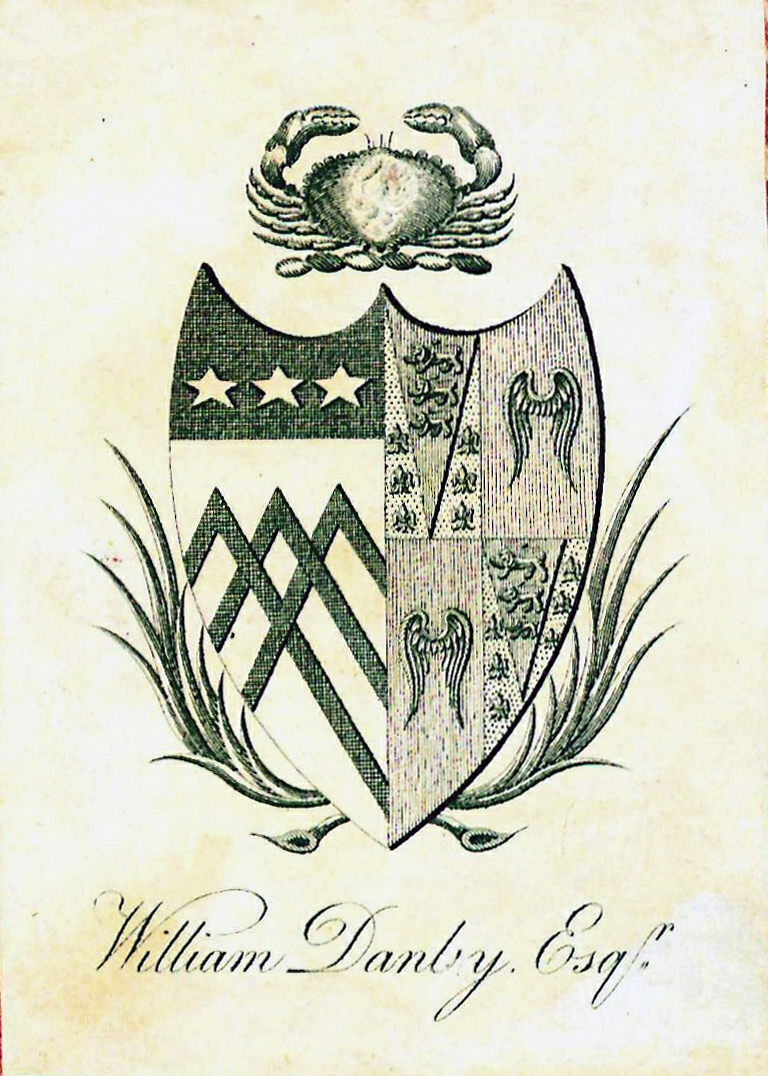

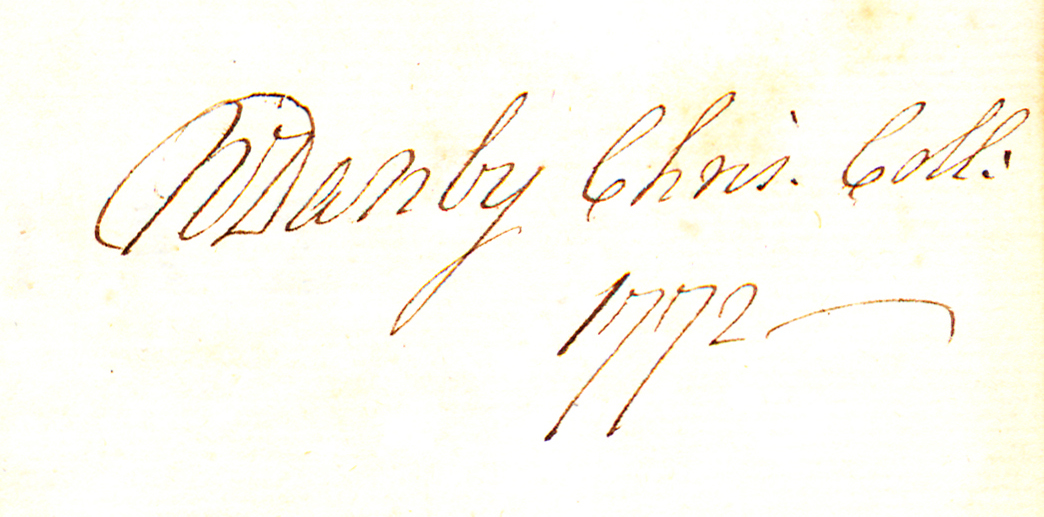

Bound in contemporary full diced brown calf with wide gilt tooled borders and five gilt stamped raised bands. Spines feature gilt lettered and elaborately gilt decorated and ornamented compartments. The edges are gilt-rolled. Includes the bookplates of William Danby (and his dated signature), Lytton Strachey, and Roger Senhouse to the front pastedown endpapers of each volume.

References

- ↑ "Homer” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Homer" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ "Homer" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World

- ↑ David Murray, Robert & Andrew Foulis and the Glasgow Press with some account of The Glasgow Academy of the Fine Arts (Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, Publishers to the University), 8.

- ↑ Ibid 3.

- ↑ Ibid 6-10.

- ↑ Philip Gaskell, A Bibliography of the Foulis Press, 2nd ed. (Winchester, Hampshire, England: St Paul's Bibliographies, 1986), 15-17.

- ↑ Ibid 17-18.

- ↑ Ibid 18-19.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on June 27, 2013, http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe