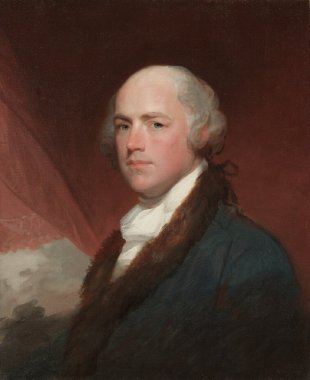

Wilson Cary Nicholas

| Wilson Cary Nicholas | |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates | |

| In office | |

| 1788-1789 | |

| Preceded by | George Nicholas |

| United States Senator | |

| In office | |

| December 5, 1799-May 22, 1804 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Tazewell |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Moore |

| Member of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office | |

| March 4, 1807-November 27, 1809 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas M. Randolph, Jr. |

| Succeeded by | David S. Garland |

| 19th Governor of Virginia | |

| In office | |

| December 1, 1814-December 1, 1816 | |

| Preceded by | James Barbour |

| Succeeded by | James P. Preston |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 31, 1761 |

| Williamsburg, Virginia | |

| Died | October 10, 1820 |

| "Tufton" in Charlottesville, Virginia | |

| Resting place | Thomas Jefferson's family graveyard at Monticello |

| Alma mater | The College of William & Mary |

| Profession | politician, soldier |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Smith |

| Relatives | Son of Judge Robert Carter Nicholas, Sr., Brother to George Nicholas |

Wilson Cary Nicholas was born in Williamsburg, Virginia, on January 31, 1761 to Robert Carter Nicholas, Sr. and Anne Cary. Nicholas' father was a prominent judge who served on the Court of Appeals, and Nicholas' mother was the daughter of an affluent Tidewater planter. [1]

Like his brother, George Nicholas, Nicholas attended the College of William & Mary to study law and may have attended George Wythe's lectures. According to Golladay's unpublished doctoral dissertation, Nicholas received his law license in September of 1778, more than a year before Wythe began lecturing. However, he may have done some additional reading under Wythe. [2] A. T. Dill maintains that both Nicholas brothers "undoubtedly read law under their father," who could not have been a better guide for their legal study. [3] Whether or not Nicholas studied law under Wythe, he left William & Mary in 1779 before he earned a degree. Instead, he commanded Virginia volunteers between the fall of 1780 and the fall of 1781. However, no evidence has been found that Nicholas actually participated in any battlefield action. [4]

Nicholas' father died in September of 1780, and Nicholas moved with his family to their extensive property in Albermarle County. There, Nicholas lived as a planter and built a new home, which he named "Mt. Warren." In 1785 he married Margaret Smith, with whom he had twelve children. [5]

In 1784 Nicholas succeeded his brother, George Nicholas, in the Virginia House of Delegates representing Albermarle County. There, Nicholas staunchly supported James Madison, particularly over Thomas Jefferson's bill for religious liberty. Nicholas' brother-in-law, Edmund Randolph, described him as a "warm friend of the Constitution without the alteration of a letter." Nicholas briefly retired from politics to his farm, but quickly drove himself into financial ruin with "disasterous forays into land speculation in southwestern Virginia." [6]

In 1794 Nicholas returned to the Virginia House of Delegates and became "a trusted Jeffersonian lieutenant." In 1799 he was elected to the United States Senate and continued to be a loyal behind-the-scenes supporter of Jefferson and a respected moderate of the Republican party. In 1804 Nicholas resigned from the Senate to accept a salaried position as Collector of U.S. Customs in Norfolk, Virginia. However, this office brought Nicholas scant financial relief and a great deal of public criticism. Consequently, Nicholas resigned within the year and returned to his farm at Mr. Warren. [7]

However, this second retirement was short lived. Jefferson soon successfully pressured Nicholas into returning to Congress, just in time for Nicholas to support the passage of the Embargo Act and James Madison's presidential nomination. Since Nicholas did most of his work behind the scenes, his political enemies saw him as "the arch-magician who pulls the strings and makes the political puppet dance." However, Nicholas soon became frustrated with Madison's policies, which he viewed as irresolute. This disenchantment coupled with attacks of rheumatism caused Nicholas to resign once more in November 1809. [8]

In 1812 Nicholas became the nineteenth governor of Virginia. He advocated a strong navy, programs of statewide public education, and state canal and turnpike networks. [9] In fact, Nicholas helped with Jefferson's plans for the University of Virginia. [10] After serving two terms as governor, Nicholas took a position as president of the Richmond branch of the Second Bank of the U.S. (again as a response to his pressing debts). However, Nicholas ran his branch too generously and collapsed in 1819. Consequently, Nicholas resigned and conveyed his entire estate to trustees. "A ruined and broken man with no unencumbered property to call his own," Nicholas died in 1820 at "Tufton" in Virginia.[11] Nicholas is buried at Monticello in the Jefferson burial ground. [12]

Jefferson recalled Nicholas as a man who "never 'possessed any shining talents or imagination' but who had provided valuable service to his state, his nation, and the party of Jefferson in the formative years of the new republic." [13]

See also

References

- ↑ American National Biography Online, s.v. "Nicholas, Wilson Cary," by Dennis Golladay, accessed March 1, 2016; "Wilson Cary Nicholas, Governor, U.S. Senator," GENi, accessed March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Victor Dennis Golladay, "The Nicholas Family of Virginia: 1722-1820" (unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Virginia, 1973), 220, 228.

- ↑ Alonzo Thomas Dill, George Wythe, Teacher of Liberty (1979), 99.

- ↑ Golladay, "Nicholas, Wilson Cary."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Wilson Cary Nicholas," The Jefferson Monticello, accessed March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Golladay, "Nicholas, Wilson Cary."

- ↑ "Virginia Governor Wilson Cary Nicholas," National Governors Association, accessed March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Golladay, "Nicholas, Wilson Cary."