Love, against Donelson and Hodgson

by George Wythe

| Love, against Donelson and Hodgson | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | George Wythe | |

| Published | n.p. (Richmond, VA?): n.p. (Thomas Nicolson?) | |

| Date | n.d. (1801?) | |

| Language | English | |

| Pages | 34 | |

| Desc. | 8vo (21 cm.) | |

Contents

Love, against Donelson and Hodgson is a published opinion by George Wythe, for the case Love v. Donelson in Virginia's High Court of Chancery.[1] Wythe states that the case took place in the "first year of the nineteenth centurie," so Love against Donelson must have been published sometime between 1801 and the year of Wythe's death, in 1806.[2] The report was published in pamphlet form in 1801 or later—almost certainly printed by Thomas Nicholson of Richmond, Virginia, who had published Wythe's Reports in 1795, and at least seven other supplements for Wythe, in 1796 and after.[3] Love v. Donelson was not reported in the second edition of Wythe's Reports, in 1852.[4][5]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Upon his death, a copy of this pamphlet which had belonged to Wythe was bequeathed with his books to Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had the pamphlet bound into a volume with seven of Wythe's other Chancery decisions which were published as supplements.[6] Subsequently, the volume became part of the collection at the Library of Congress, titled on the spine: Wythe's Reports. Supplement. Virginia. 1796-99 (despite this case taking place in 1801).[7] The pamphlet for Love against Donelson has a handwritten notation, "no. 7," on the first page.

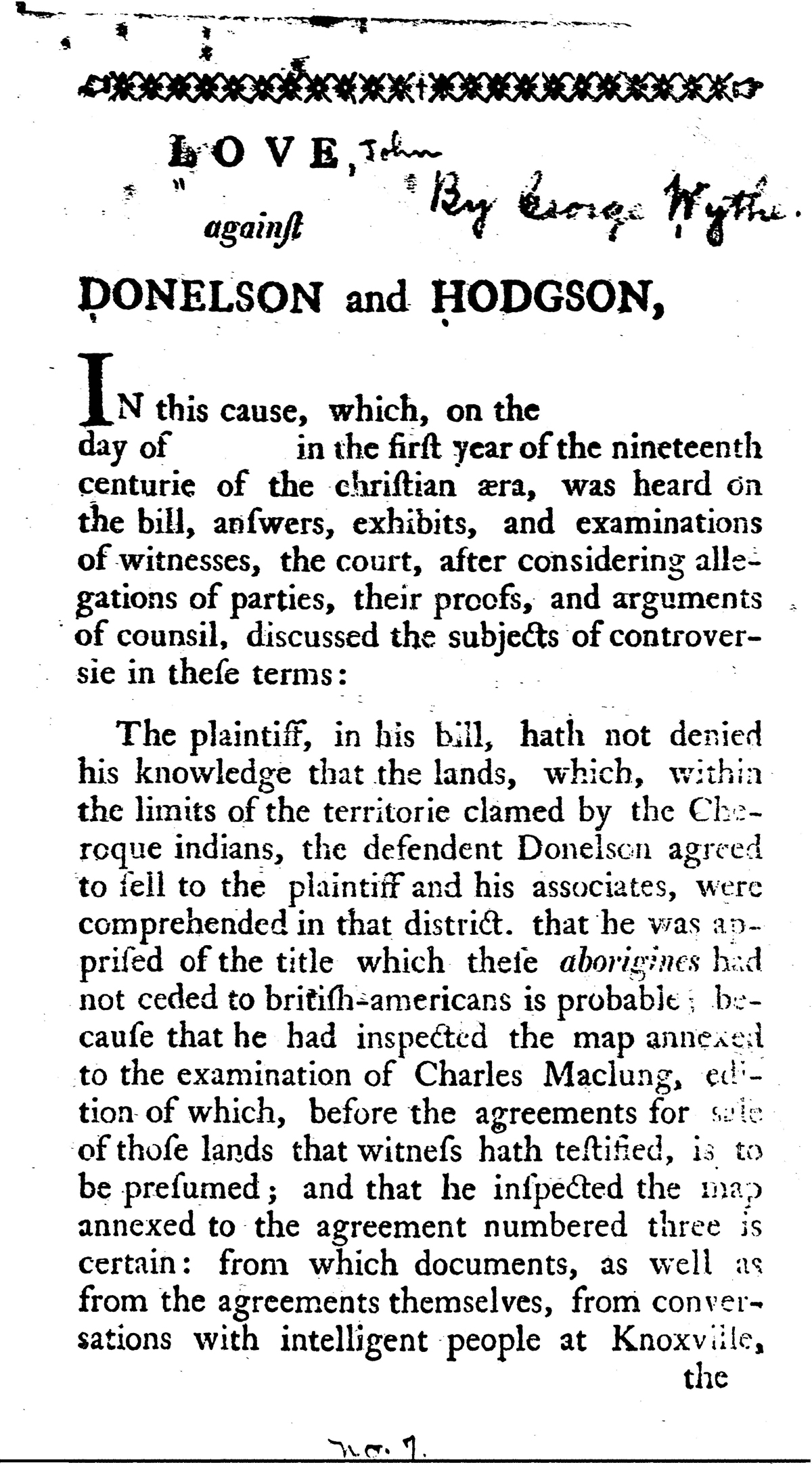

Several pages of the pamphlet contain manuscript corrections by Wythe in his hand, including a footnote in Greek, apparently scraped off and corrected to 'Κάλχας Θεστορίδης οἰωνοπόλων': "Calchas, son of Thestor, far the best of augurs" (bird-diviners).[8] On another page Wythe made a notation in the margin referring to Taylor's Elements of the Civil Law (1769).[9]

Document text, 1801

Page 1

LOVE,

against

DONELSON and HODGSON,

IN this cause, which, on the day of in the first year of the nineteenth centurie of the christian æra, was heard on the bill, answers, exhibits, and examinations of witnesses, the court, after considering allegations of parties, their proofs, and arguments of counsil, discussed the subjects of controversie in these terms:

The plaintiff, in his bill, hath not denied his knowledge of that lands, which, within the limits of the territorie clamed by the Cheroque indians, the defendent Donelson agreed to fell to the plaintiff and his associates, were comprehended in that district. that apprised of the title which these aborigines had not ceded to british-americans is probable; because that he had inspected the map annexed to the examination of Charles Maclung, edition of which, before the agreements for sale of those lands that witness hath testified, is to be presumed; and that he inspected the map annexed to the agreement numbered three is certain: from which documents, as well as from the agreements themselves, from conversations with intelligent people at Knoxville,the

Page 2

the scene of the transaction, and from the public offices, the plaintiff might have derived, and is believed to have derived, all the information which the defendent could communicate.

But he (Donelson) was, by the terms of the agreements, and of covenants in the conveyances, that he would warrant generaly, sponsor as well against indians as against all other men. so that

The defendent Donelson, if for him, in his own name, judgment had been rendered in an action upon the bond which was dischargeable in the ninety sixth year of the eighteenth centurie, would have been enjoined from obtaining the whole of the money recovered, or so much of it as is equal to the price of what lands sold by him to the plaintiff were abdicated by the british americans in the treaty between them and the indians.

Against the other defendent, to whom the bond was assigned, and in whose name judgment was entered, if he had known the origin of the debt, and especialy if he had known too that the seller of the lands for the price of which the bond was given had not a title to them, like relief would have been extended: but such knowledge was denied by that defendent in his answer, which hath not been disproved.

Ought the plaintiff, then, to be relieved against the defendent Hodgson, an unconciousassignee,

Page 3

assignee, for a valuable consideration, of the bond?

In august of the eighty ninth year of the eighteenth centurie this court delivered the following opinion:

'An obligator is not intitled to relief against the obligation in the hands of the assignee, who, having paid a valuable consideration for it without knowledge of unfairness in the sale of a negro, for payment of the price whereof the obligation was granted, and who being impowered by statute to commence and prosecute an action in his own name, had a legal right to the money acknowledged by the obligation to be due, and whose equity was not less than the obligors equity.' Chancery decisions, folio 115: where objections to the opinion are answered.

In opposition to it are these words of the supreme judicatorie of this commonwealth, in the case of Norton against Rose, reported by Washington, 2 vol' p' 254:[10] the court is of opinion, that an assignee of a bond or obligation takes the same, subject to all the equity of the obligor, conformably with which opinion a decree of the high court of chancery was reserved.

Orthodoxie of the sentence pronounced by the judges of appeal will be here examined in this commentarie; where the names of the par-ties

Page 4

ties in this case shall be put for the names of the parties in that:

Roane, j'. Upon the principles of the common law, a chose en action is not assignable, that is, the assignment does not give to the assignee a right to maintain an action in his own name.] If Love oblige himself to pay twenty thousand dollars to Donelson, or to his assignee, and Donelson assign the obligation to Hodgson for value received of him, who was neither party nor privy to the contract between the two former, and if the common law, inhibiting assignment of a chose en action, had never existed, the right of Hodgson to so much of the money as had not been paid before assignment, would have been the same as if that remainder had been, by terms of the obligation, payable immediately to himself, without pervading Donelson. for,

In the case supposed, the obligation is resolvable into this sense: I, John Love, acknowledging myself indebted twenty thousand dollars to Stockley Donelson, agree to pay them, if he order them to be paid, to William Hodgson, and the money would, after such order, that is, the assignment, have been due to tis last no less truly than it would have been due if he had been due if he had been original obligee, except that he must have discounted payments to Donelson, who would have been a mere fistula or pipe through which the obligation of Love was conveyedWhat

Page 5

What hath been said is undeniable, as the commentator ventureth to suppose. if the supposition be not rash,

Since the statute, which, giving validity to translation of such chose en action, and, for recovery therof, authorising assignees in their own names to prosecute actions, hath silenced the common law, Donelsons intervention in the transaction cannot affect the right of Hodgson, otherwise than that Love is entitled to the discounts mentioned before and to be defined hereafter.

In England, the assignee of a bond takes it charged with every species of equity which was attached to IT in the hands of the obligee.] This is intelligible and true in case of such an obligation as this:

Know all men that i John Love am held bound unto Stockely Donelson in 40000 dollars, to be paid to him, or to his assigns, for which payment i bind my representatives, as well as myself. this obligation however shall be void if, on or before the day, &c', i pay to him 20000 dollars, the price of certain lands which he hath sold to me, covenanting that he hath a title to them, and that they are unemcumbered.

If the terms of the bond do not shew or lead to inquire for what cause the money, thereby acknowledged to be due, became due, the wordsof

Page 6

of the text, 'equity attached to it in the hands of the obligee,' seem inexplicable. to attach is to take hold of something. from Stockley Donelson selling land, which was not his, to John Love, and taking an obligation for payment of the price, the deceived purchaser had a right to demand restitution of the obligation; for that, deprived of the things bought, he should retain their price, by which the evidence of the debt indicates that he was to merit them, is equity. parties would have then been in status quo they were before the bargain, or would have been after performance of it by both. of this equity, when it is expanded or inscribed on, or may be investigated from something apparent in, the instrument signifying altern obligations of the parties, may be predicated, that the equity is attached to the bond, by the words of which those obligations may be conjectured, if not discovered. the parts of the contract, for example, on the side of Stockley Donelson, that John Love shall permanently and quietly possess lands sold to him, and, on the side of John Love, that Stockley Donelson, for assurance of this benefit, shall receive an adstipulated retribution, are attached mutally, or have hold of, are connected with, each other, in whose hands soever may be the bond or writing which is evidence of the contract.

But what can be the meaning of 'equity attached' to a simple bond, obliging one topay

Page 7

pay money, for which the law supposeth him to have received value, when the cause of the contract doth not appear by the bond itself? can the obligees equity have hold of any part of, or be connected with any syllable in, the bond?

If a different principle in this country, it must grow out of the acts of assembly, which authorised the assignment of bonds.] The proposition, condemned by the court of appeals, 'grew out of,' or was a deduction from, those acts of assembly giving energy to this principle: of contending parties he, who, having an equitable title, acquireth a fair legal title also, to the thing in question, shall prevale against him who hath an equitable title only: which principle was not long ago supported by jurisprudentes to be no more disputable than the axiom, the whole is greater than its part, is supposed by geometricians to be deniable. that Hodgson, an unconscious assignee for value, hath an equitable title is admitted; the statute, authorising him to prosecute an action in his own name, gave him a legal title; and that Love hath any more than equitable title is not pretended. such reasoning as this, in the case between Norton and Rose was the 'ground' of the high court of chanceries decree, which CLARIFIED judges reprobated, one, who 'CLEARLY entertained his opinion upon the subject, pronouncing the ground of the decreeto

Page 8

to be wrong (p' 251;) another professing himself upon the whole to be CLEAR that the decree was erroneous' (p' 253;) and with them a third, 'upon the whole also concurring' (p' 254.)

The acts &c.'] Three line here might as well been any where, or no where, else.

This case depends upon the construction of the act of 1748.] Instead of this construction, which is not once attempted, we are often told what was the intention and the design of the act.

The intention of it, &c'] In these words and the rest of te paragraph we learn nothing more than what we learn by barely reading the statute itself.

It was not intended to abridge the rights of the obliger,] Before the statute, against the assignee the obligor had a right to oppose his equitable demands; why? becasue the assignee had no more than an equitable right. but after the statute, which gave a legal right to the assignee, against him, armed with two rights one equitable the other legal, could the obligor oppose his single equitable right? were not the former more potent, was not the latter more feeble; and consequently was not this adbridged? if the statute, by conclusion inevitable, 'hath abridged the right of the obligor,' bywhat

Page 9

what authority can a judge thus affirm, that 'to abridge the rights of the obligor was not intended?' he is required to exhibit the diploma constituting him explorer of the legislative intention, when legislative words have not revealed it.

Or to enlarge those of the assignee, beyond, &c] The statute, giving to the assignee one right more than he had before, namely, the right of recovering by an action prosecuted in his own name, doubled his rights, and, if a thing doubled is enlarged, and if the court of appeals will permit the legislature to know their intentions, 'to enlarge the rights of assignees was intended.'

And since it is clear, that, prior to this law, an original equity attached to the bond,] Attachment to the simple bond is denied.

Followed it into the hands of the assignee,] The passport of this equity against the obligee into the assignees hands, before the statute, was revoked by the statute; for in contradiction to what is asserted in the text, that

This law does not expressly, nor by implication destroy the principle.] Is affirmed, that the law, when it gave the legal right to the assignee, did, by necessary implication and inevitable infe-rence, '

Page 10

rence, 'destroy that principle' as it is called: because the assignees legal right by the statute, combined with his equitable right, being duplicate, triumphed over the obligors right, which was solitary.

Notes of hand are now assignable in England, and it is admitted that the assignee is discharged of any equity, which existed against the assignor, unless the note was given, for an usurious, or for a gaming consideration.] The assignee here is supposed before the statute to have been charged with, for otherwise he could not have been discharged of, 'the equity' which 'existed against the assignor.' the supposition is not true. The assignee, before the statute could not assert his own right, which was but an equitable right, and which the drawers equity therefore impeded, and could not assert the payees right, which, if he retained the note, would have been defeated by the drawers equity.

The reason of this is not that the principle attached to them as a legal consequence of their being made assignable,] To prove the reason here disallowed to be the true reason hath been attempted.

But because this rule, for commercial purposes, applied to bills of exchange, and the statute of Anne,[11] declaring notes assignable in like man-ner

Page 11

ner as bills of exchange, shewed an intention, as it was supposed, to render the former as highly negociable and as current in internal, as the latter was in external commerce.] This was intended to teach, that in England, if the words 'in like manner as bills of exchange,' had been omitted in the statute of Anne, assignees of promisory notes would have been charged with assignors equity. to prove it a single argument, better than the princippii petitio, hath not been urged. yet to disprove it shall be here essayed.

A bill of exchange is transferable or assignable, that is, he, who by bill of exchange hath a right to demand money, may pass that right, or give it currency, to others in one or another of these manners; either by writing his name under these or like words, 'pay the contents to the assignee' naming him, or by writing the assignors name, without any superscription. in both manners, the writings are called indorsements, because usualy placed on the back, in dorso, of the bill; and that indorsement which is nude is equivalent to the other, the holder there being assignee.

In the statute of Anne, the words; 'promisory notes, payable to order or bearer, may be assigned and endorsed, and action maintains thereon in like manner as inland bills of exchange,' mean neither more nor less than these words: 'promisory notes, payable to or-der,

Page 12

der, or bearer, may be assigned and endorsed by the assignor, writing his name under these or like words, 'pay the contents to the 'assignee,' or by writing or endorsing the assignors name, not superscribed, or in blank as it is called, and action maintained thereon.' this parap^hrase, the rectitude of which no man of candor will dare to deny, clearly proves that the MANNER of authorising the passage, the NEGOTIABILITY, or the CURRENCY, changes not the thing to which is given passage, NEGOTIABILITY, or CURRENCY, whether it be by an indorsement on the same or writen on a separate paper, or by any other MANNER.

If this be correct, and if the words 'in like manner as bills of exchange' had not been in the statute of Anne, promisory notes would have been negotiable, or in the phrase of the text as highly negotiable, as they nor are; perhaps more negotiable, because the statute which prescribed the manner of negotiation, that is by indorsement, must be persued, whereas, if the words, in like manner as inland bills of exchange' had been omited, promisory notes might have been negotiated, or assigned, in some other MANNER.

The learned judges doctrine, therefore, is unsound and bonds made assignable as negotiable, in this country, as bills of exchange andpromisory

Page 13

promisory notes are, in England,^with the exception as to legal discounts; and that they should not be so no part of the statute hath been quoted to prove. a question by the reporter p' 243, 244, 'why inland bills and noted of hand should, and bonds should not, be governed by the same rule of law?' than which a question more apposite could not have been invented, was overlooked by the court of appeals.

The act of our assembly embraces equaly the subject of bonds and notes, but contains no expressions tending to induce a belief that the making them assignable, was intended for purposes of commerce.] For what purposes, then, if not for the purposes of buying, selling, bartering, that is, of commerce, was assignment of bonds made valid? and let this other question propounded by the reports, in his argument, p' 246, 'if the equity said to be originaly attached to the bond would follow it into the hands of an assignee, upon principles unaffected by this law, why was the law made?' which question was also neglected, be remembered. the construction as it is called, which the judges of appeal made of the statute will give it no effect but this; to render an irrevocable letter of attorney to the assignee unnecessary.

The design certainly was to make them transferable to a certain extent;] Where is its termination?The

Page 14

The provision] What provision? if the statute, what clause, line, or word, of it

Points out the limits of their negotiability,] Hath indicated and defined these limits?

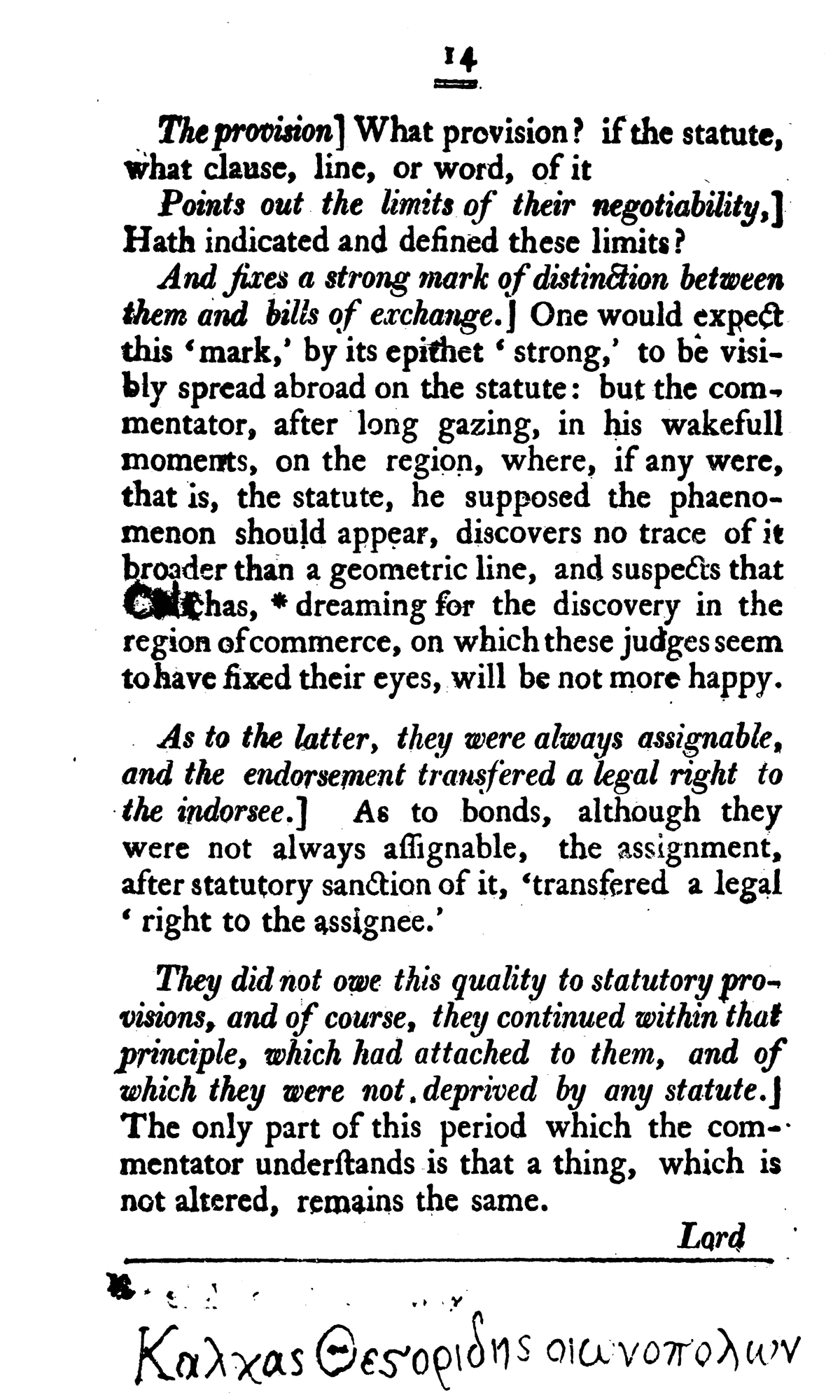

And fixes a strong mark of distinction between them and bills of exchange.] One would expect this 'mark,' by its epithet 'strong,' to be visibly spread abroad on the statute: but the commentator, after long gazing, in his wakefull moments, on the region, where, if any where, that is, the statute, he supposed the phaenomenon should appear, discovers no trace of it broader than a geometric line, and suspects that Calchas,* dreaming for the discovery in the region of commerce, on which these judges seem to have fixed their eyes, will be not more happy.

As to the latter, they were always assignable, and the endorsement transfered a legal right to the indorsee.] As to bonds, although they were not always assignable, the assignment, after statutory sanction of it, 'transfered a legal right to the assignee.'

They did not owe this quality to statutory provisions, and of course, they continued within that principle, which had attached to them, and of which they were not, deprived by any statute.] The only part of this period which the commentator understands is that a thing, which is not altered, remains the same.Lord

* Κάλχας Θεστορίδης οἰωνοπόλων

Page 15

Lord Mansfield lays it down, in the case of Peacock and Rhodes, Dougl' 636,[12] that the holder of a bill of exchange, or promisory note, is not to be considered in the light of an assignee of the payee.] This only affirms assignee of a promissory note to be in a better state than payee; because the assignor, by his endorsement, is bound as well to the drawer, to discharge the note.

An assignee must take the thing assig^ned, subject to all the equity to which the original party was subject: if this rule applied to bills and promissory notes it would stop their currency.] Mansfields reasoning, if it be not misunderstood, is, the currencies by indorsation of bills of exchange, and by assignment or indorsation of promisory notes, to one of which customary law and to the other statutory law gave sanction, would be interrupted, if the rule, that an assignee 'must take the thing assigned subject to all the equity to which the original party was subject,' applied to those commercial media. now to what inference doth analogie point? planely this: the rule applies not to syngraphs, instruments, to which, signifying the holders credits, customary or statutory law hath attributed NEGOTIABILITY OR CURRENCY. and bonds being in that predicament, the consectarie is, the rule doth apply, not to bonds assigned but, only to instruments which have no legal CURRENCY, OR NEGOTIABILITY.So

Page 16

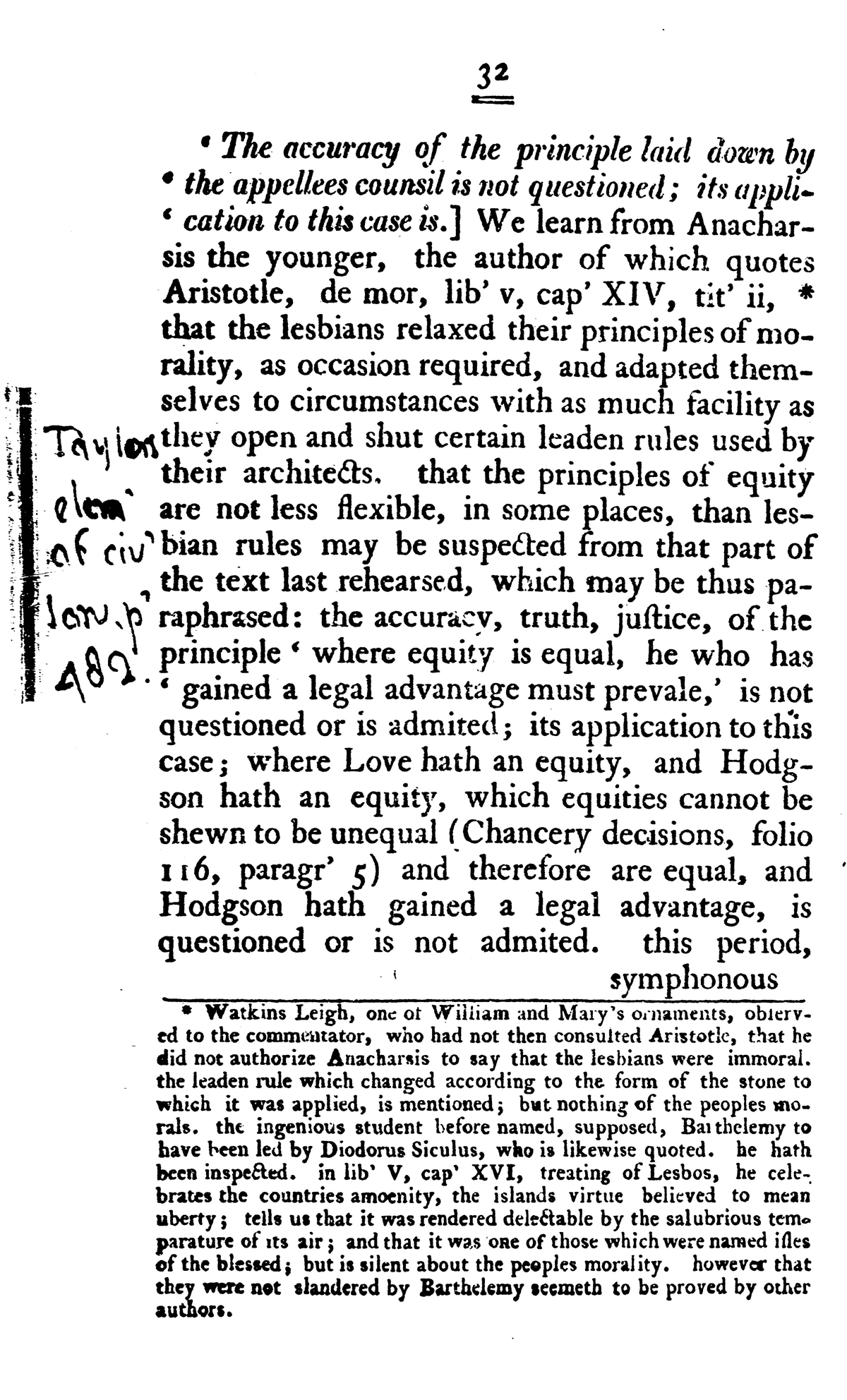

Page one from Wythe's pamphlet, "Love, Against Donelson and Hodgson" (1801?). Copy at the Library of Congress.

Page 13 from Wythe's pamphlet, "Love, Against Donelson and Hodgson" (1801?). Copy at the Library of Congress.

Page 14 from Wythe's pamphlet, "Love, Against Donelson and Hodgson" (1801?), with Wythe's correction for the footnote: Κάλχας Θεστορίδης οἰωνοπόλων. Copy at the Library of Congress.

Page 32 from Wythe's pamphlet, "Love, Against Donelson and Hodgson" (1801?). Copy at the Library of Congress.

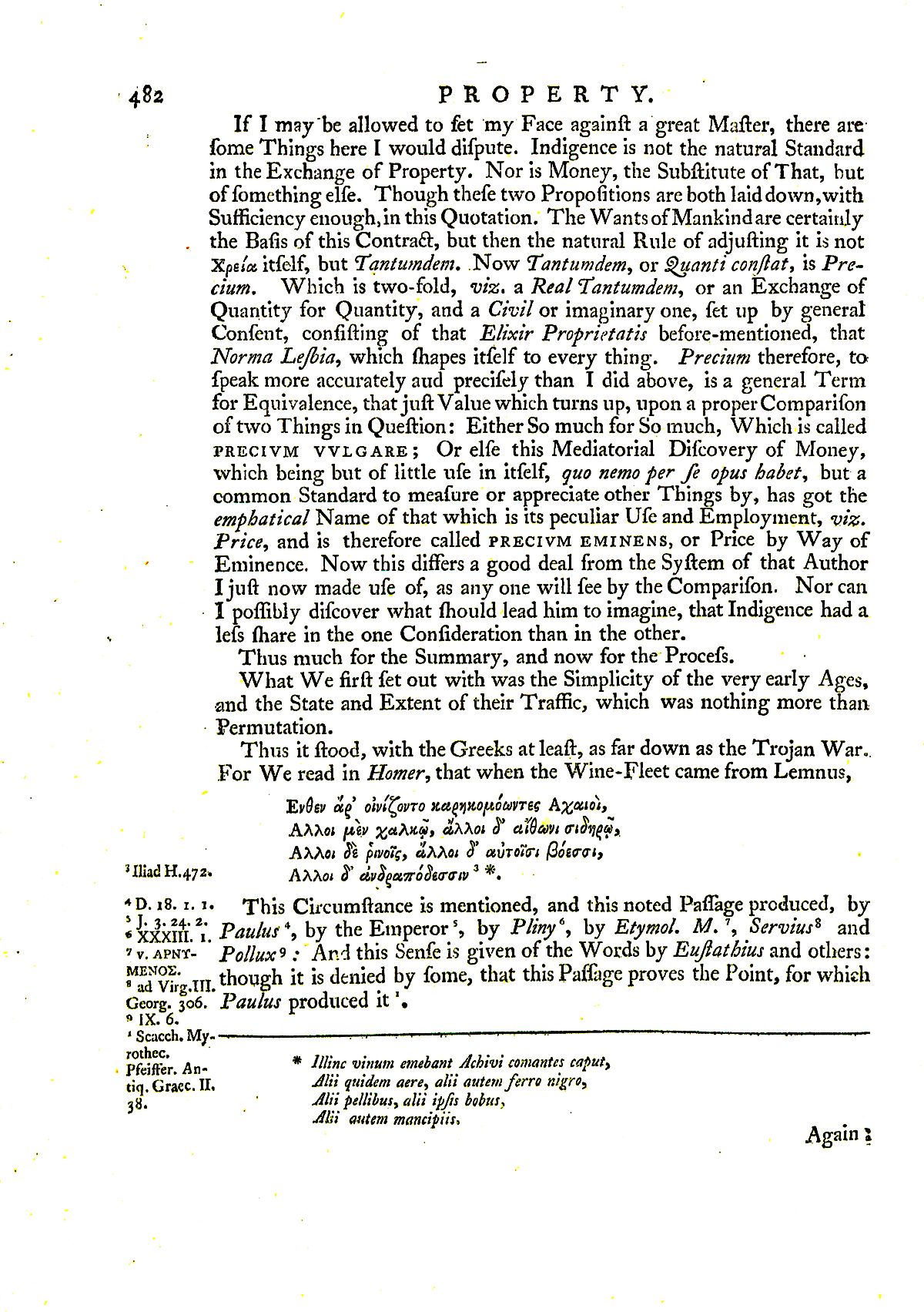

Page 482 of the third edition of John Taylor's Elements of the Civil Law (London: Charles Bathurst, 1769), with Wythe's reference to the "Norma Lesbia, which shapes itself to every thing."

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Love, against Donelson and Hodgson (Richmond, VA: Thomas Nicolson, 1801?).

- ↑ It is the opinion of the editors that the Chancellor would have understood that the new century began January 1, 1801. A similar reference to 1789 being the "eighty ninth year of the eighteenth centurie" (p. 3 in this report) supports this conclusion.

- ↑ Charles Evans, in his American Bibliography, vol. 11 (1942), mistakenly gives the date of publication as 1796.

- ↑ Benjamin Blake Minor, ed., Decisions of Cases In Virginia, By the High Court Chancery, with Remarks Upon Decrees By the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, by George Wythe (Richmond, Virginia: J.W. Randolph, 1852), xli.

- ↑ Minor had access to a bound volume of pamphlets which had belonged to James Madison, and was then in the possession of William Green of Culpeper, Virginia. The Catalogue of the Choice and Extensive Law and Miscellaneous Library of the late Hon. William Green, LL.D.,... to be sold by Auction, January 18th, 1881, at Richmond, VA. (Richmond: John E. Laughton, Jr., 1881), lists the volume as follows (p. 200). Mysteriously missing from the catalogue, however, is an entry for Between Yates and Salle, specifically mentioned by Minor to have been issued as a pamphlet, presumably provided by Green (Minor, p. 163).

2325. WYTHE'S REPORTS. Aylett & Aylett, Richmond: 1796; Field & Harrison, Richmond: 1796. WYTHE (GEO.). Case upon the Statute for Distribution, Richmond: 1796. Wilkins & John Taylor, et als.; Fowler & Saunders. In one vol., 12mo. Auto. of President James Madison. Ms. notes. A rare collection of the Original Imprints, supposed by the late possessor to be unique.

- ↑ "Six tracts originally bound together in calf for Jefferson by Milligan on June 30, 1807 (cost $1.00). Rebound in Buckram for the Library of Congress." E. Millicent Sowerby, comp., Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1953), 2:208.

- ↑ Library of Congress catalog record. This volume contains pamphlets for: Case upon the Statute for Distribution (1796); Field v. Harrison (1794); Fowler v. Saunders and Goodall v. Bullock (1798, together in the same pamphlet); Wilkins v. Taylor (1799); Yates v. Salle (1792); and Love v. Donelson (1801). See also: Aylett v. Aylett (1793), and Overton v. Ross (1803).

- ↑ Calchas was the prophet of Troy. Homer, Iliad 1.69.

- ↑ "Manuscript notes by Wythe." Sowerby, 2:209.

- ↑ Norton v. Rose 2 Wash. 233 (Va. 1796).

- ↑ 3 & 4 Anne, cap. 9.

- ↑ William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield. Peacock v. Rhodes 2 Doug. 633.

See also

- American Bibliography

- Between Fowler and Saunders

- Between Wilkins and Taylor

- Between Yates and Salle

- The Case of Overtons Mill: Prolegomena

- Case upon the Statute for Distribution (pamphlet)

- Love v. Donelson

- Report of the Case between Aylett and Aylett

- Report of the Case between Field and Harrison

External links

- Library of Congress catalog record.

- Sowerby Catalogue, at HathiTrust.