Difference between revisions of "Palaia Diatheke Kata tous Hebdomenkonta"

m |

|||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

|year=1665 | |year=1665 | ||

|pages=[1283] p. | |pages=[1283] p. | ||

| − | |desc=[[:Category: | + | |desc=[[:Category:Duodecimos|12mo]] (15 cm.) |

|shelf=B-1 | |shelf=B-1 | ||

}}The Early Christian Church used the Greek texts "The translation, which shows at times a peculiar ignorance of Hebrew usage, was evidently made from a codex which differed widely in places from the text crystallized by the Masorah (..) Two things, however, rendered the Septuagint unwelcome in the long run to the Jews. Its divergence from the accepted text (afterward called the Masoretic) was too evident; and it therefore could not serve as a basis for theological discussion or for homiletic interpretation. This distrust was accentuated by the fact that it had been adopted as Sacred Scripture by the new faith [Christianity] (..) In course of time it came to be the canonical Greek Bible (..) It became part of the Bible of the Christian Church. <ref> "Bible Translations – The Septuagint|url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/3269-bible-translations|publisher=JewishEncyclopedia.com|accessdate=10 February 2012}}</ref> since Greek was a ''lingua franca'' of the Roman Empire at the time, and the language of the Greco-Roman Church (Aramaic was the language of Syriac Christianity, which used the Targumim). | }}The Early Christian Church used the Greek texts "The translation, which shows at times a peculiar ignorance of Hebrew usage, was evidently made from a codex which differed widely in places from the text crystallized by the Masorah (..) Two things, however, rendered the Septuagint unwelcome in the long run to the Jews. Its divergence from the accepted text (afterward called the Masoretic) was too evident; and it therefore could not serve as a basis for theological discussion or for homiletic interpretation. This distrust was accentuated by the fact that it had been adopted as Sacred Scripture by the new faith [Christianity] (..) In course of time it came to be the canonical Greek Bible (..) It became part of the Bible of the Christian Church. <ref> "Bible Translations – The Septuagint|url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/3269-bible-translations|publisher=JewishEncyclopedia.com|accessdate=10 February 2012}}</ref> since Greek was a ''lingua franca'' of the Roman Empire at the time, and the language of the Greco-Roman Church (Aramaic was the language of Syriac Christianity, which used the Targumim). | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

[[Category:Cambridge]] | [[Category:Cambridge]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Duodecimos]] | ||

Revision as of 12:33, 5 April 2023

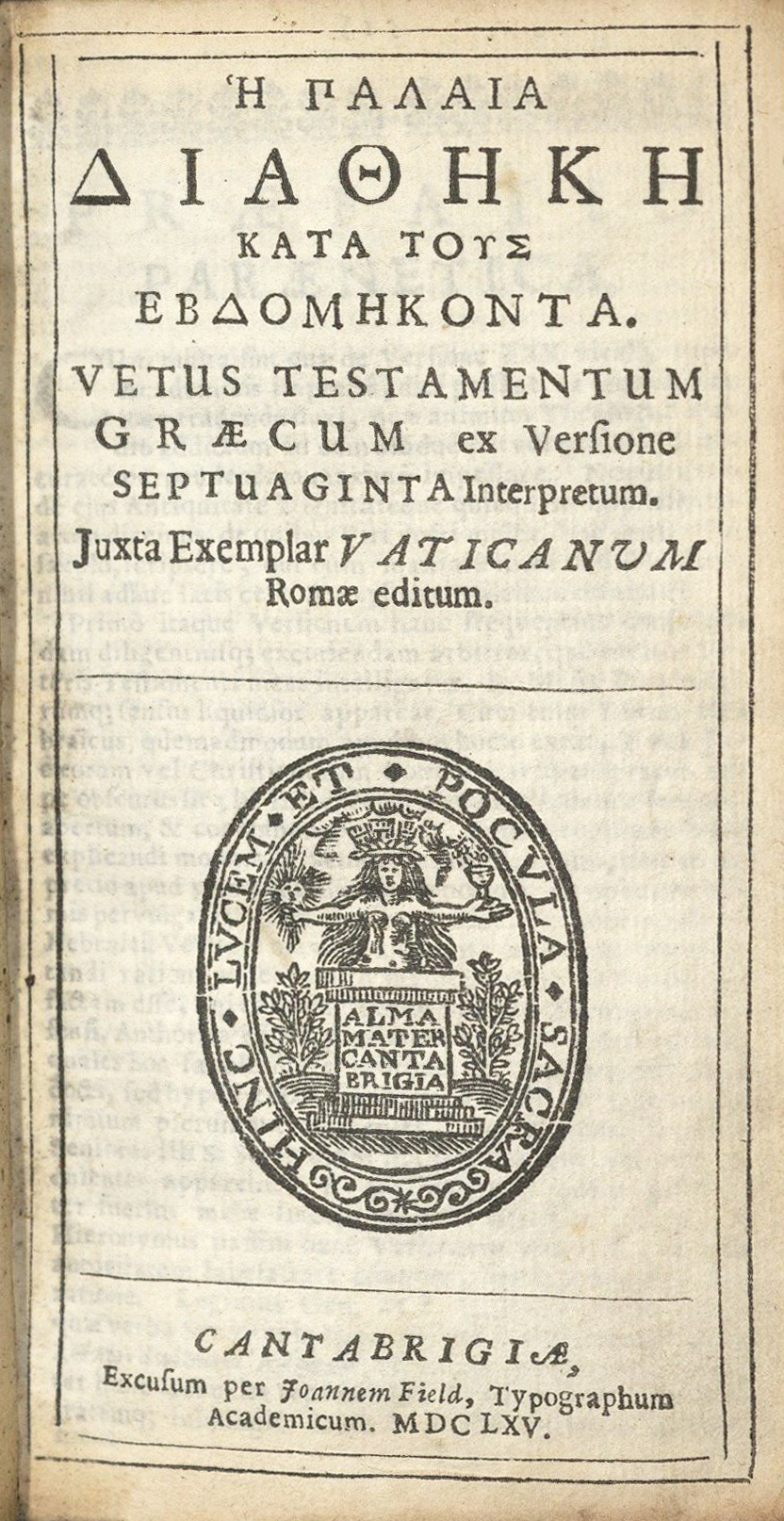

| Vetus Testamentum | |

|

Title page from Vetus Testamentum, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Published | Cantabrigiæ: Excusum per Joannem Field |

| Date | 1665 |

| Language | Greek |

| Pages | [1283] p. |

| Desc. | 12mo (15 cm.) |

| Location | Shelf B-1 |

The Early Christian Church used the Greek texts "The translation, which shows at times a peculiar ignorance of Hebrew usage, was evidently made from a codex which differed widely in places from the text crystallized by the Masorah (..) Two things, however, rendered the Septuagint unwelcome in the long run to the Jews. Its divergence from the accepted text (afterward called the Masoretic) was too evident; and it therefore could not serve as a basis for theological discussion or for homiletic interpretation. This distrust was accentuated by the fact that it had been adopted as Sacred Scripture by the new faith [Christianity] (..) In course of time it came to be the canonical Greek Bible (..) It became part of the Bible of the Christian Church. [1] since Greek was a lingua franca of the Roman Empire at the time, and the language of the Greco-Roman Church (Aramaic was the language of Syriac Christianity, which used the Targumim).

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "'Testamentum vetus LXXII. et novum. 3.v. 12mo. Cantab. 1665" This was one of the titles kept by Thomas Jefferson and later sold to the Library of Congress in 1815. Both the Brown Bibliography[2] and George Wythe's Library[3] on LibraryThing include the 1665 edition published in Cambridge based on Jefferson's notation and Millicent Sowerby's entry in Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson.[4] Unfortunately, Jefferson's copy no longer exists. As yet, the Wolf Law Library has been unable to procure a copy of Palaia Diatheke Kata tous Hebdomenkonta.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

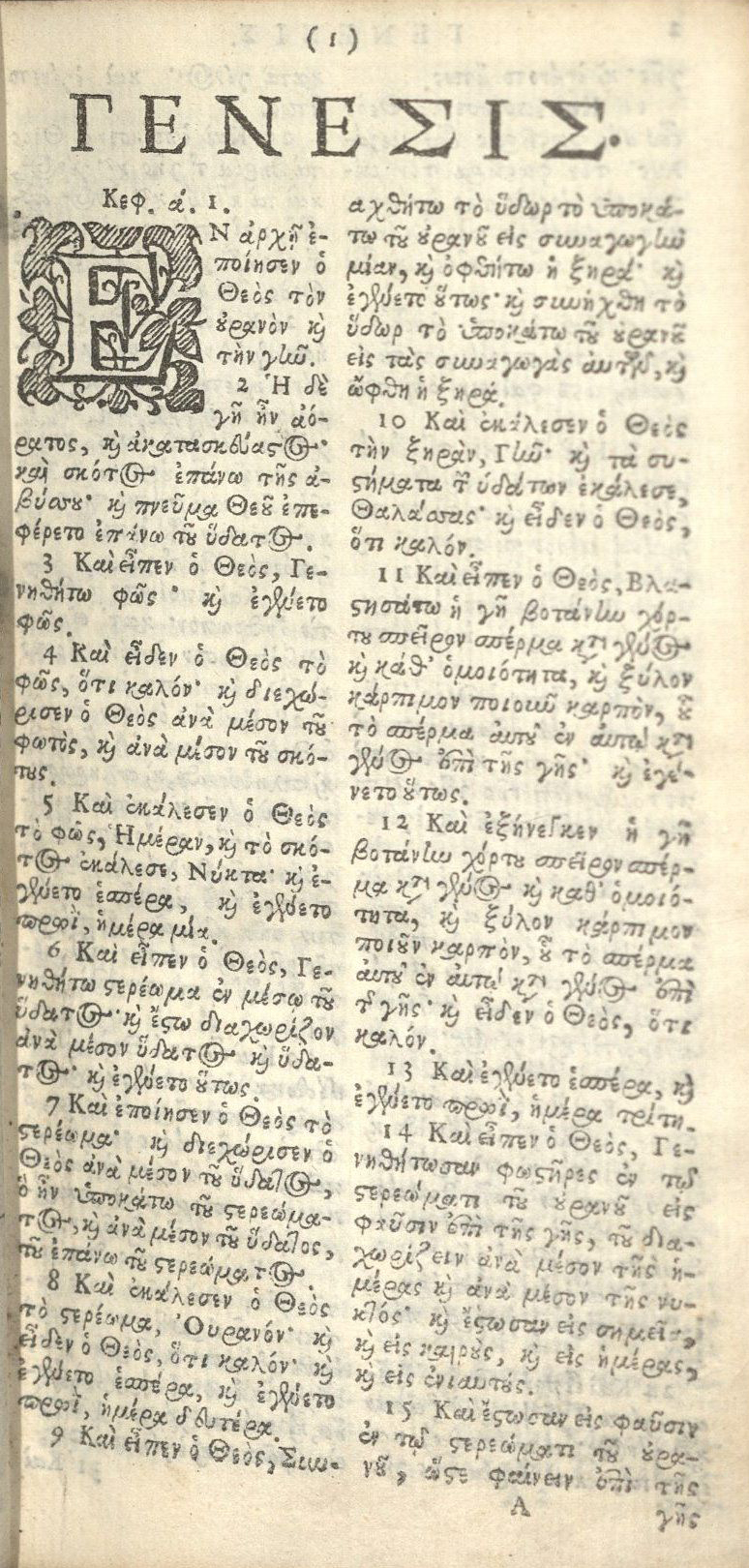

Bound in contemporary leather, four raised bands to spine.

Images of the library's copy of this book are available on Flickr. View the record for this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

See also

- George Wythe Room

- The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments

- Jefferson Inventory

- Hē Kainē Diathēkē. Novum Testamentum

- Tes Kaines Diathekes Apanta = Novum Testamentum

- Tēs Kainēs Diathēkēs Hapanta = Novum Testamentum

- Psaltērion Psalterium

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ "Bible Translations – The Septuagint|url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/3269-bible-translations%7Cpublisher=JewishEncyclopedia.com%7Caccessdate=10 February 2012}}

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on January 31, 2014.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 2:100 [no.1481]