Difference between revisions of "George Wythe and Slavery"

m (→Slavery and Wythe's Heritage) |

m (→Wythe's Slaves) |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

As noted above, George Wythe did own slaves. Records from 1748 document Wythe's sale of a Negro slave girl, Lucy, to his mother's brother-in-law.<ref>Indenture of George Wythe, May 3, 1748, ''Deeds, Wills, Etc., 1736-1753,'' 282, Elizabeth City County Records. ''Cf.'' entry of that date, ''Order Book, 1747-1755,'' 33. Cited in William Edwin Hemphill, "[[George Wythe the Colonial Briton#Page 49|George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia]]" (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 1937), 49.</ref> In 1776 one of Wythe's slaves, a man named Charles, was placed in the Williamsburg jail for an unknown charge and later sentenced to work in the lead mines in western Virginia.<ref>H.R. McIlwaine, ed., [[Journal of the the Council of the State of Virginia, 13 July 1776|''Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia'']] (Richmond, VA: The Virginia State Library, 1931), 1:70-71. It is unclear why Charles was put in jail or how long he worked in the lead mines. However, it is possible that Charles was the same slave freed by Wythe in 1788. Mary A. Stephenson, ''[http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports%5CRR1483.xml&highlight= George Wythe House Historical Report, Block 21]'' (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, 1952).</ref> For some authors, Wythe's involvement in slavery, both owning and selling them, supports the conclusion that Wythe's opinions on slavery developed later in his life.<ref>Clarkin, ''Serene Patriot'', 9.</ref> However, prior to the passage of "An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves" (1782), Virginia law prohibited slave owners from freeing slaves without the government's permission.<ref>"An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves." 11 Henning Statute's at Large 39 (May 1782). Private manumission laws were necessary for any future abolition in the South. Winthrop D. Jordan, ''White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro'' (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), 347. Prior to this law, private manumission was forbidden in Virginia. Robert M. Cover, ''Justice Accused: Antislavery and the Judicial Process'', (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975) 67.</ref> Under the Manumission Act, Wythe freed most of his slaves in 1787.<ref>Stephenson, ''George Wythe House Historical Report''.</ref> | As noted above, George Wythe did own slaves. Records from 1748 document Wythe's sale of a Negro slave girl, Lucy, to his mother's brother-in-law.<ref>Indenture of George Wythe, May 3, 1748, ''Deeds, Wills, Etc., 1736-1753,'' 282, Elizabeth City County Records. ''Cf.'' entry of that date, ''Order Book, 1747-1755,'' 33. Cited in William Edwin Hemphill, "[[George Wythe the Colonial Briton#Page 49|George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia]]" (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 1937), 49.</ref> In 1776 one of Wythe's slaves, a man named Charles, was placed in the Williamsburg jail for an unknown charge and later sentenced to work in the lead mines in western Virginia.<ref>H.R. McIlwaine, ed., [[Journal of the the Council of the State of Virginia, 13 July 1776|''Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia'']] (Richmond, VA: The Virginia State Library, 1931), 1:70-71. It is unclear why Charles was put in jail or how long he worked in the lead mines. However, it is possible that Charles was the same slave freed by Wythe in 1788. Mary A. Stephenson, ''[http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports%5CRR1483.xml&highlight= George Wythe House Historical Report, Block 21]'' (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, 1952).</ref> For some authors, Wythe's involvement in slavery, both owning and selling them, supports the conclusion that Wythe's opinions on slavery developed later in his life.<ref>Clarkin, ''Serene Patriot'', 9.</ref> However, prior to the passage of "An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves" (1782), Virginia law prohibited slave owners from freeing slaves without the government's permission.<ref>"An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves." 11 Henning Statute's at Large 39 (May 1782). Private manumission laws were necessary for any future abolition in the South. Winthrop D. Jordan, ''White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro'' (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), 347. Prior to this law, private manumission was forbidden in Virginia. Robert M. Cover, ''Justice Accused: Antislavery and the Judicial Process'', (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975) 67.</ref> Under the Manumission Act, Wythe freed most of his slaves in 1787.<ref>Stephenson, ''George Wythe House Historical Report''.</ref> | ||

| − | At any given time, Wythe likely had ten to twenty slaves at his home in Williamsburg. The 1783 Williamsburg Personal Property Tax recorded that Wythe had fourteen slaves, but by 1788, that number had dwindled to three.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Upon the death of Wythe's wife, [[Elizabeth Taliaferro Wythe]] in 1787, Wythe | + | At any given time, Wythe likely had ten to twenty slaves at his home in Williamsburg. The 1783 Williamsburg Personal Property Tax recorded that Wythe had fourteen slaves, but by 1788, that number had dwindled to three.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Upon the death of Wythe's wife, [[Elizabeth Taliaferro Wythe]] in 1787, Wythe gave eleven of his slaves to the children of his brother-in-law, Richard Taliaferro.<ref>Lyon G. Tyler, "[[George Wythe's Gift]]," ''William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine'' 12, no. 2 (October 1902), 125-126.</ref> It is likely that those slaves were originally a part of Elizabeth's inheritance from her father.<ref>Lyon G. Tyler, "[[Will of Richard Taliaferro]]," ''William and Mary Quarterly Historical Magazine'' 12, no. 2 (October 1903), 124-125; Robert B. Kirtland, ''George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge'' (New York: Garland, 1986), 140.</ref> The law may have required Wythe to return "property" that belonged to Elizabeth back to her father, because the couple were childless and Elizabeth died without an heir.<ref>Tyler, "Will of Richard Taliaferro," 124-125.</ref> Wythe did free the last three slaves that he owned in 1788.<ref>Stephenson, ''George Wythe House Historical Report'' (citing the 1787-1788 York County records).</ref> [[Lydia Broadnax]] — Wythe's cook for years in Williamsburg and in Richmond — was one of them. There is some dispute about the number of slaves that Wythe freed or transferred at this time, but most sources conclude that after Elizabeth's death, Wythe rid himself of all of his personal slaves through one means or another.<ref>Kirtland, ''George Wythe'', 141; Holt, Wythe, "[http://www.law.ua.edu/pubs/lrarticles/Volume%2058/Issue%205/Holt.pdf George Wythe: Early Modern Judge]," ''Alabama Law Review'' 58, no. 5 (2007): 1026 (stating that Wythe had seventeen slaves total in 1784 and that he transferred thirteen of those slaves after his wife's death); Bailey, ''Jefferson's Second Father'', 195 (stating that the total number of transferred slaves was sixteen).</ref> |

Along with the slaves in Williamsburg, Wythe also owned slaves at the Chesterville family plantation, in what is now Hampton, Virginia.<ref>John Nierson, ''[[Complaint regarding the estate of Frances Wythe|Complaint Regarding the Estate of Frances Wythe]]'' c. 1793. Norfolk County Court Records. Library of Virginia.</ref> In his will, Wythe's older brother, Thomas, bequeathed his slaves equally between his wife, Frances Wythe, and his niece, Euphan Sweeney Claiborne.<ref>Ibid.</ref> According to a 1793 complaint filed with the Norfolk County court, George Wythe "purchased of his Brothers widow all her right to the said slaves."<ref>Ibid.</ref> The plantation, along with Frances Wythe's slaves, transferred to the ownership of George Wythe. As for the slaves bequeathed to his niece, Wythe, "by desire of his mother, without receiving any consideration," gave at least ten slaves to his niece and her husband Thomas Claiborne. It is unclear how many slaves were left at the Chesterville plantation after this transfer. We know that Wythe spent little time at the plantation, instead hiring a manager to watch over the land and the slaves.<ref>Blackburn, ''George Wythe of Williamsburg'', 85.</ref> | Along with the slaves in Williamsburg, Wythe also owned slaves at the Chesterville family plantation, in what is now Hampton, Virginia.<ref>John Nierson, ''[[Complaint regarding the estate of Frances Wythe|Complaint Regarding the Estate of Frances Wythe]]'' c. 1793. Norfolk County Court Records. Library of Virginia.</ref> In his will, Wythe's older brother, Thomas, bequeathed his slaves equally between his wife, Frances Wythe, and his niece, Euphan Sweeney Claiborne.<ref>Ibid.</ref> According to a 1793 complaint filed with the Norfolk County court, George Wythe "purchased of his Brothers widow all her right to the said slaves."<ref>Ibid.</ref> The plantation, along with Frances Wythe's slaves, transferred to the ownership of George Wythe. As for the slaves bequeathed to his niece, Wythe, "by desire of his mother, without receiving any consideration," gave at least ten slaves to his niece and her husband Thomas Claiborne. It is unclear how many slaves were left at the Chesterville plantation after this transfer. We know that Wythe spent little time at the plantation, instead hiring a manager to watch over the land and the slaves.<ref>Blackburn, ''George Wythe of Williamsburg'', 85.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 12:12, 26 February 2018

Thomas Jefferson stated that George Wythe was "unequivocal" on the issue of slavery,[1] implying that Wythe left no doubt about his opposition to human bondage. A honest look into Wythe's life, however, requires context to explain Jefferson's statement. For a majority of his life, Wythe owned slaves. Indeed, he was in his early 60s when he put beliefs into practice and removed all slavery connections from his life. Publicly, Wythe benefited from the institution of slavery; but evidence reveals that Wythe opposed slavery, publicly and privately. Unlike any other Virginian of his time, Wythe appeared to believe in the inherent equality between the Negro and the white races. As Chancellor, Wythe frequently decided cases that applied property law to slaves. Yet, when given the chance to decide on issues of freedom and equality, Wythe put his private beliefs into practice. These beliefs also influenced many of his students to oppose the institution of slavery.

Contents

Slavery and Wythe's Heritage

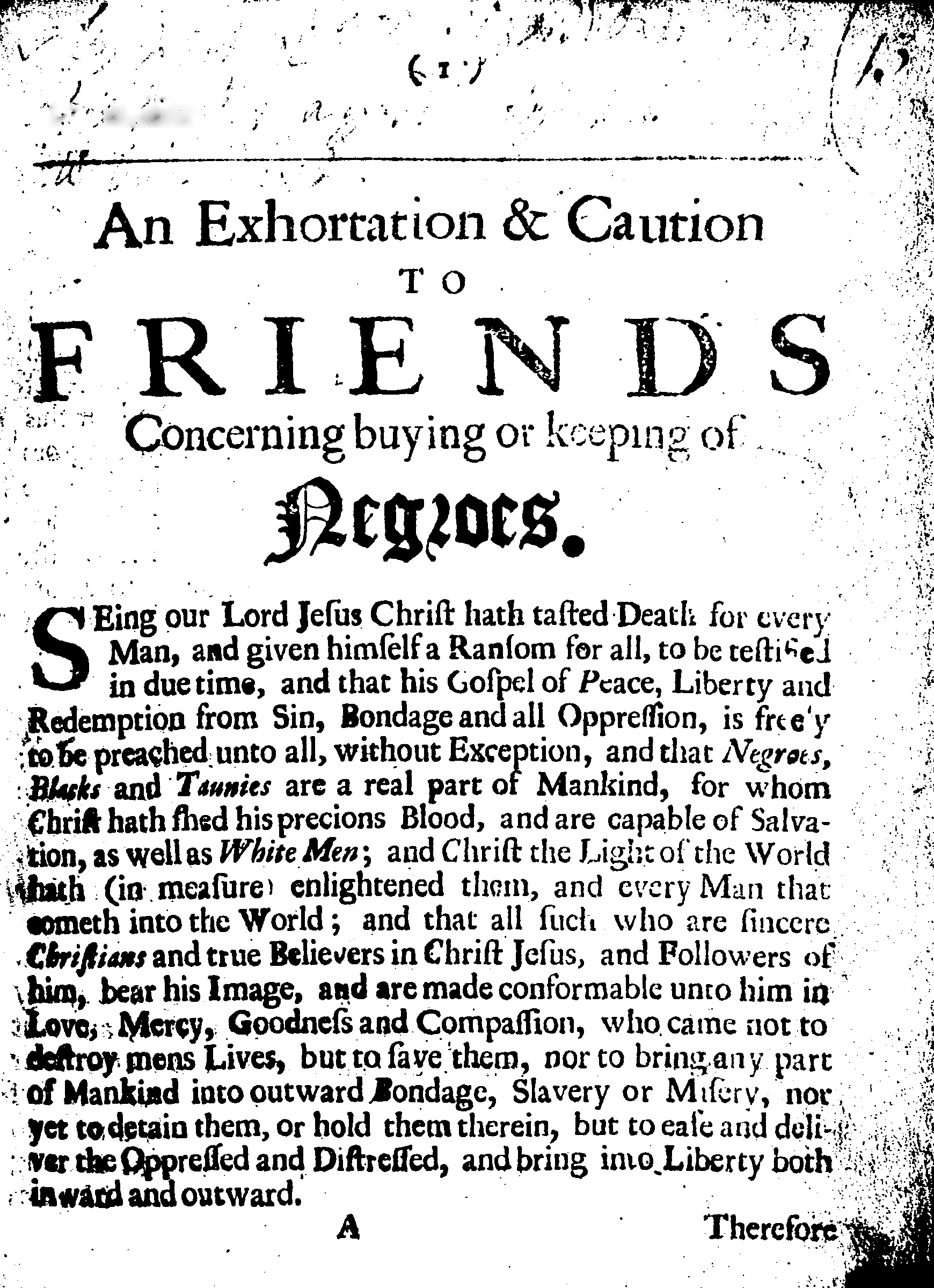

Some authors argue that Wythe's anti-slavery viewpoint traces back to his maternal great-grandfather, George Keith, through the education Wythe received from his mother.[2] Keith began his religious career as a Quaker minister and used his influence in the Quaker community to oppose slavery.[3] In 1693, Keith published An Exhortation & Caution to Friends Concerning Buying or Keeping of Negroes, the first Quaker tract to urge manumission.[4] Keith later converted to the Church of England, but he retained his abolitionist views.[5] Keith died before Wythe was born, but his influence on the family likely trickled down through his daughter, Anne Walker (Wythe's grandmother) and granddaughter, Margaret Walker Wythe (Wythe's mother). Although never a Quaker himself, Wythe's maternal religious lineage does seem to have influenced him.[6] Wythe's parents, however, owned slaves at their Chesterville home, so Margaret may not have shared her grandfather's anti-slavery worldview.[7] Regardless, Wythe's views correspond well with those of the great-grandfather who composed the first Quaker abolitionist manifesto.[8]

|

List of Named Slaves |

|

Wythe's Slaves

As noted above, George Wythe did own slaves. Records from 1748 document Wythe's sale of a Negro slave girl, Lucy, to his mother's brother-in-law.[9] In 1776 one of Wythe's slaves, a man named Charles, was placed in the Williamsburg jail for an unknown charge and later sentenced to work in the lead mines in western Virginia.[10] For some authors, Wythe's involvement in slavery, both owning and selling them, supports the conclusion that Wythe's opinions on slavery developed later in his life.[11] However, prior to the passage of "An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves" (1782), Virginia law prohibited slave owners from freeing slaves without the government's permission.[12] Under the Manumission Act, Wythe freed most of his slaves in 1787.[13]

At any given time, Wythe likely had ten to twenty slaves at his home in Williamsburg. The 1783 Williamsburg Personal Property Tax recorded that Wythe had fourteen slaves, but by 1788, that number had dwindled to three.[14] Upon the death of Wythe's wife, Elizabeth Taliaferro Wythe in 1787, Wythe gave eleven of his slaves to the children of his brother-in-law, Richard Taliaferro.[15] It is likely that those slaves were originally a part of Elizabeth's inheritance from her father.[16] The law may have required Wythe to return "property" that belonged to Elizabeth back to her father, because the couple were childless and Elizabeth died without an heir.[17] Wythe did free the last three slaves that he owned in 1788.[18] Lydia Broadnax — Wythe's cook for years in Williamsburg and in Richmond — was one of them. There is some dispute about the number of slaves that Wythe freed or transferred at this time, but most sources conclude that after Elizabeth's death, Wythe rid himself of all of his personal slaves through one means or another.[19]

Along with the slaves in Williamsburg, Wythe also owned slaves at the Chesterville family plantation, in what is now Hampton, Virginia.[20] In his will, Wythe's older brother, Thomas, bequeathed his slaves equally between his wife, Frances Wythe, and his niece, Euphan Sweeney Claiborne.[21] According to a 1793 complaint filed with the Norfolk County court, George Wythe "purchased of his Brothers widow all her right to the said slaves."[22] The plantation, along with Frances Wythe's slaves, transferred to the ownership of George Wythe. As for the slaves bequeathed to his niece, Wythe, "by desire of his mother, without receiving any consideration," gave at least ten slaves to his niece and her husband Thomas Claiborne. It is unclear how many slaves were left at the Chesterville plantation after this transfer. We know that Wythe spent little time at the plantation, instead hiring a manager to watch over the land and the slaves.[23]

Near the end of the American Revolution, Wythe's Chesterville manager deserted the plantation.[24] In December of 1781, Wythe wrote to Jefferson that he would come to Monticello if "[his] presence at Chesterville were not indispensably necessary to adjust my affairs left there in some confusion by the manager who hath lately eloped."[25] During this time, one of Wythe's Chesterville slaves, a man named Neptune, was caught as a runaway and sent back to Wythe after being imprisoned.[26] Many of the other Chesterville slaves may have run away or escaped to fight for the British and the promise of freedom.[27] When Wythe returned to Chesterville to settle his affairs, he may have had only two or three elderly slaves remaining.[28]

Wythe tasked Daniel L. Hylton to sell Chesterville.[29] This suggests that Wythe transferred the deed to Hylton, rather than just hiring him to sell it. A 1795 advertisement indicates that at least some slaves were included in the first attempt to sell the plantation.[30] It described the plantation's advantages as including "the land, the orchard, the livestock and negroes, and the following buildings..."[31]

Wythe's first attempt to sell Chesterville was unsuccessful; Hylton did not manage to restore and sell the land, so Wythe forced a sheriff's sale and reacquired the deed.[32] Wythe finally sold Chesterville to Holder Hudgins in 1801 without making a large profit.[33] Some authors suggest, considering that Wythe freed his personal slaves earlier, that Wythe's lack of profit in the sale supports the argument that he also freed those slaves left at Chesterville.[34] The lack of profit, however, could also be explained if the sale included only a few elderly slaves. Unfortunately, the relevant Elizabeth County property records were destroyed during the Civil War, making it impossible to know exactly what transpired.[35]

Lydia Broadnax, continued to work as Wythe's cook, as a free woman, until his death.[36] When Wythe moved to Richmond in 1790, Lydia followed. There has been some speculation that an interracial relationship existed between Broadnax and Wythe.[37] This speculation suggests that Michael Brown — a mulatto boy who also lived with Wythe — was the son of Broadnax and Wythe.[38] However, this theory has been largely debunked.[39] Wythe and Broadnax's age provide the strongest argument against this allegation. Broadnax would have been in her fifties and Wythe in his late sixties at the time of Brown's birth.[40] The allegation first appears in a document known as the Dove memo, a statement by Dr. John Dove of his memories surrounding Wythe's death. The Dove memo has been regarded as an untrustworthy source due to the circumstances surrounding its creation.[41] Most authors conclude that the allegation of impermissible relations between Broadnax and Wythe was likely fabricated.[42] It is more likely that Lydia was married to Ben, another freed slave who worked for Wythe.[43]

Wythe's treatment of his freed slaves suggests that he regarded them to be the same as white persons. Wythe not only paid Lydia for her cooking services, but also provided her housing apart from his residence.[44] Additionally, Wythe made sure that other people paid Lydia when she worked in her capacity as a paid servant.[45]

As for Michael Brown, there is no clear consensus as to where he came from. We do know that Wythe took it upon himself to educate Brown as he would any other student, including teaching him Latin and Greek.[46] In his will, Wythe devised the estate so that Lydia, Ben, and Michael each received a portion.[47] Wythe also requested that Jefferson teach Brown after Wythe's death, furthering his belief that the boy should be educated like his white counterparts.[48] However, this never came to pass because Brown died at the same time as Wythe, most likely at the hands of George Wythe Sweeney, Wythe's great nephew.[49] Broadnax was the only freed servant that survived Wythe's death.[50]

Wythe's Views on Slavery

Private Beliefs

During his lifetime, those closest to Wythe knew him to be avidly opposed to slavery. In 1785, Jefferson wrote that Wythe's, "sentiments on the subject of slavery are unequivocal."[51] During the Revolution, Wythe and Jefferson corresponded on the issue of runaway slaves.[52] Wythe was aware of several negroes in the area suspected to be slaves.[53] Based on that information, Wythe requested that Jefferson send him a description of the servants Jefferson expects are missing.[54] The request likely indicates that if found, Wythe planned to return the runaways to Jefferson. Nevertheless, Wythe does seem to truly hold the view that slavery was an evil that needed to be eradicated.[55] Other Virginians at the time theoretically opposed slavery while practically enjoying the its benefits.[56] Arguably, Wythe should be included in that group, but he differed significantly on one point: the equality of the Negro race.[57]

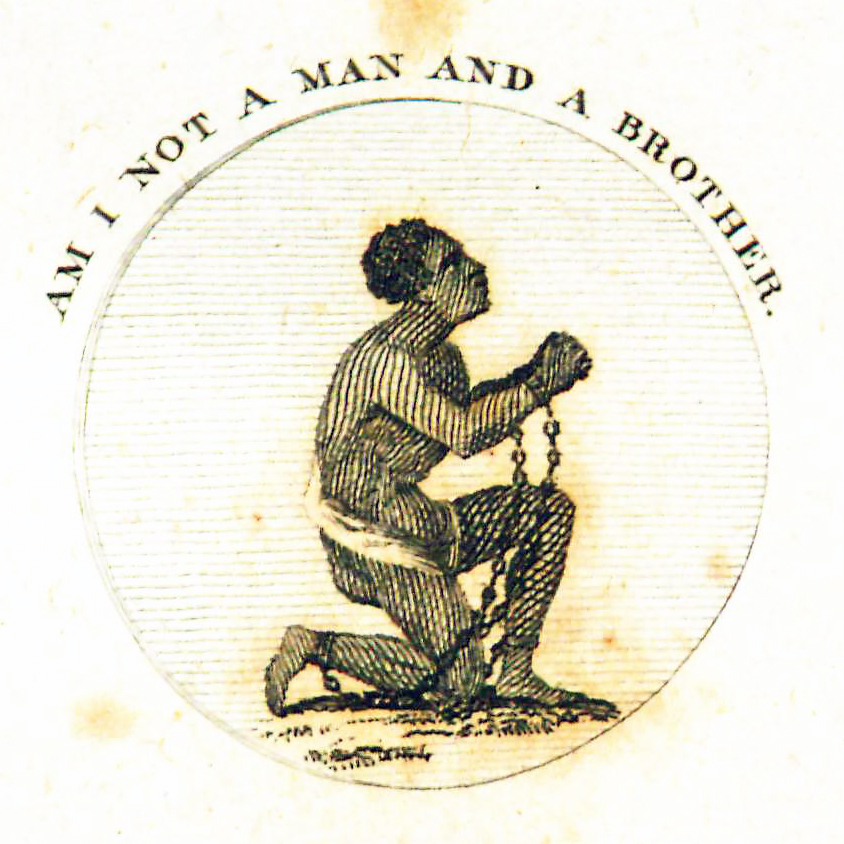

Wythe believed that the Negro race held the full attributes of humanity, and that they could be educated like whites.[58] Because Wythe's view was somewhat novel,[59] he sought to prove equality through experiments in education.[60] Specifically, Wythe tested "the theory that there was no natural inferiority of intellect in the negro, compared with the white man,"[61] and Wythe taught slaves to read and write in the same manner as his white students.[62] The Chancellor also taught Michael Brown Greek, Latin, and natural science until the time of his death.[63] Wythe's opinion that the Negro race was equal also affected how he viewed abolition. Benjamin Watkins Leigh wrote in 1832 that "Mr. Wythe, to the day of his death, was for simple abolition."[64] Simple abolition required the freedom of slaves without any method of deportation or removal.[65]

Wythe's support for simple abolition was contrary to the typical views of abolition in the south.[66] For example, Jefferson stood for abolition that required the transfer of the slaves to another location once they were free.[67] Wythe opposed this type of plan because he believed that it was an "objection to color as founded in prejudice."[68] Wythe may have been the only Virginian to attempt to prove the absence of inferiority between the races.[69]

Public Actions

Prior to George Wythe's time as a judge, the issue of slavery came up frequently in his professional life. Even if Wythe's personal anti-slavery position stayed consistent, he played a role in perpetuating the evil institution. For example, in 1770, Wythe represented a slave owner who wanted to keep his mulatto servants as slaves.[70] Jefferson, the attorney for the other side, argued that the law should be on the side of freeing the slaves — the same argument that Wythe would later use himself in his slavery opinions as Chancellor.[71] The case Howell v. Netherland, cannot truly speak to Wythe's public views because the court ruled in favor of the defendant without giving Wythe the opportunity to speak.[72] However, the case does demonstrate that Wythe did not allow his personal views to prevent him from representing slave owners.

During the revolution, Wythe's public duties also intersected with the issue of slavery. The number of slaves fleeing to fight for the British army in exchange for freedom concerned General George Washington.[73] As a member of the Continental Congress, Wythe served on the committee addressing this issue.[74] After the war, Wythe, Jefferson, and Edmund Pendleton worked to restructure Virginia's constitution and laws.[75] In the original draft, they included a provision providing for the gradual manumission of slaves.[76] The provision was never presented to any legislative body, it is documented in Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia[77] where he wrote "[t]he public mind would not yet bear the proposition."[78] Wythe and Jefferson did use this opportunity to reduce some of the more heinous Virginia laws against slaves, such as eliminating certain punishments and banning the further importation of slaves.[79]

Wythe and Jefferson did not attempt to dismantle the institution.[80] Had they tried, any such suggestion would have been readily rejected.[81] But by 1795 there was a slight shift in Virginia on the issue of slavery.[82] In November of that year, Wythe was one of many petitioners who sent the House of Delegates a draft requesting an anti-slavery act that would free slaves born after its passing.[83] The petition also asserted that members of the Negro race were not inferior, but created by God just like members of the white race.[84] Although unsuccessful, it demonstrates that Wythe contributed to some public anti-slavery sentiment.[85] It was not until Wythe was Chancellor that his public position truly displayed the same fervor.

Wythe's Views as Chancellor: Judicial Decisions Concerning Slavery

As Chancellor, Wythe often decided cases that dealt with slaves being transferred as property upon the death of their owner.[86] Wythe applied the law as written, which treated slaves as property,[87] even when it conflicted with his personal views.[88] Some authors suggest that this supports the argument that Wythe chose to use the "mask of the law" to avoid having to test the veracity of his private views.[89] But, Wythe did put his beliefs into practice as Chancellor. In the rare instances where Wythe was faced with a slave's freedom, the Chancellor went beyond the existing law and argued for a fundamental right to freedom.[90] In Pleasants v. Pleasants and Hudgins v. Wrights, Wythe made legal arguments that provided freedom for slaves.[91] In both cases, the Court of Appeals affirmed Wythe's conclusions but explicitly disregarded his legal and ethical challenges to the institution of slavery.[92]

The issue in Pleasants was whether John Pleasant's will requiring that all of his slaves be set free when private manumission was possible could be upheld in court.[93] The legal administrators under the will opposed manumission and wanted that portion struck down as unenforceable.[94] Using well-crafted legal tools, Wythe concluded that the will could be enforceable, thereby freeing over eight hundred slaves.[95] One of the first cases to explore the legal foundations of the Virginia Manumission Act,[96] Wythe concluded that the Act could apply retroactively because it restored a slave's natural right to freedom.[97] Wythe viewed the request for freedom as a "restitution of a right, of which they ... could not have been deprived without violation of equitable constitutional principles."[98] Because Wythe argued that manumission was grounded in natural law and slavery was not, Pleasants could legally stipulate this kind of contingency in his will.[99] Further, Wythe refused to interpret Pleasants' allocation of freedom as a conditional gift, writing that transfer of property laws have little applicability in cases where, "human liberty is challenged." Thus, Wythe's decision in Pleasants centered on his belief that human rights trump property rights when freedom is challenged.[100] Along with enforcing the slaves' legal right to freedom, Wythe also held that the slaves be paid for their period of wrongful enslavement.[101] Wythe's decision was a shock to those of the time, particularly because it freed hundreds of slaves and required the owners to provide back pay.[102] The Court of Appeals upheld Wythe's judicial conclusion to enforce the will, but reversed his order of back pay.[103]

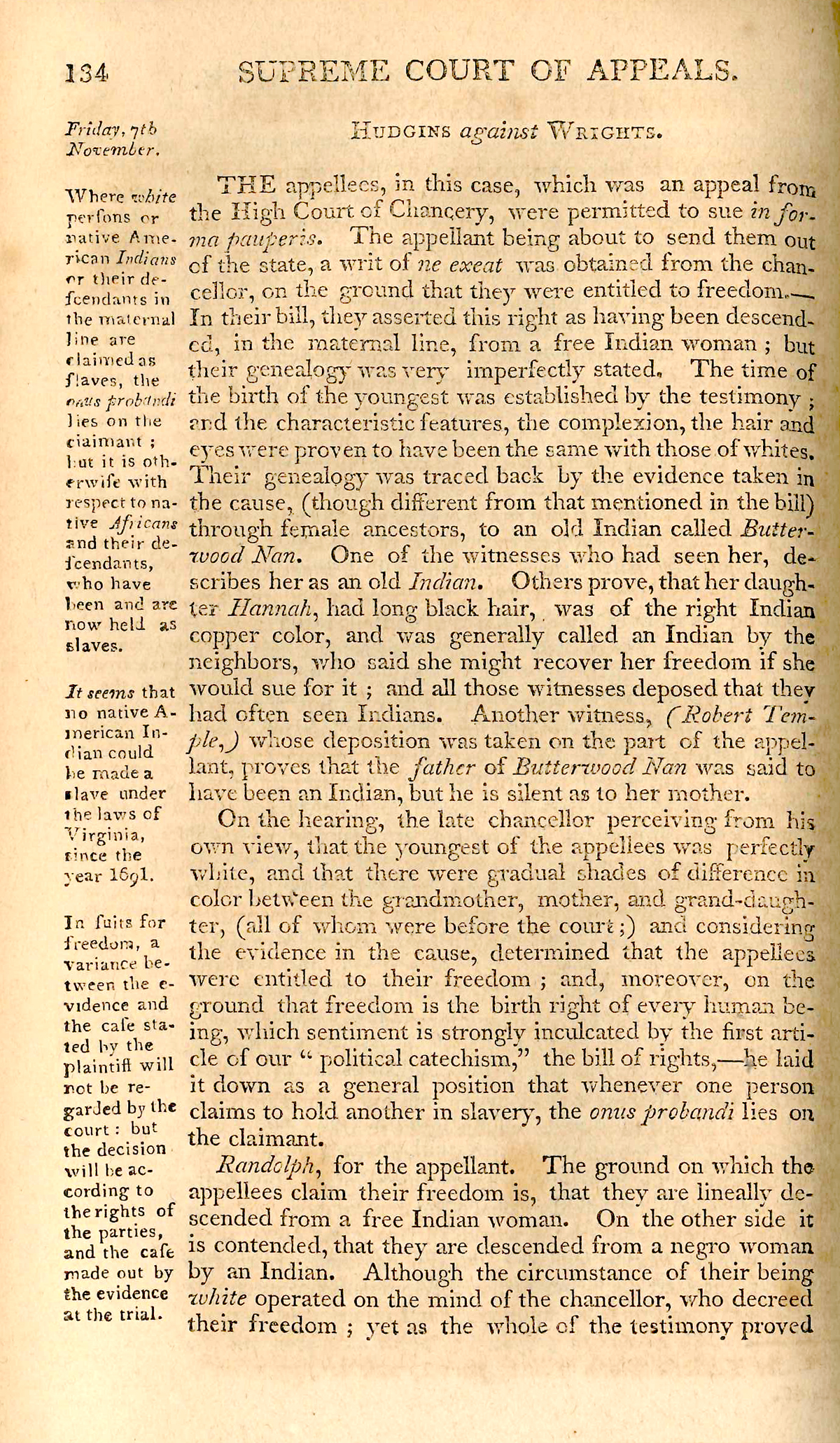

Wythe insinuated that freedom was a fundamental right for all races in Pleasants; he explicitly stated that conclusion a few years later in Hudgins v. Wrights.[104] Although, the original Chancery opinion of this case has not been preserved, Wythe's arguments can be gleaned from the Court of Appeals decision.[105] In Hudgins, Wythe was faced with slaves who claimed freedom based on their Indian heritage.[106] By law, people of Indian decent were presumed free in the courts.[107] Wythe found that the Wrights were of Indian decent, and he could have decided the case on this narrow ground.[108] Instead, Wythe declared that under Virginia law, all people were presumed free because freedom came from a natural right.[109] He concluded that when an enslaved person requests freedom the burden is on the slave owner to prove that the person should be enslaved.[110] Wythe based this conclusion "on the ground that freedom is the birthright of every human being, which sentiment is strongly inculcated by the first article of our 'political catechism,' the bill of rights." [111]

Wythe's belief, that all people — even Negroes — had a natural right to freedom caused great disruption.[112] The Court of Appeals affirmed Wythe's decision, but only on the narrow ground that the Wrights were of Indian decent.[113] The court unanimously rejected Wythe's reasoning that all races had an intrinsic right to freedom.[114] Instead, they reaffirmed that people of the Negro race have the burden of proving a right to freedom.[115] Wythe surely knew that his attempt to end slavery in Virginia would be futile, but it is possible that as he neared the end of his life putting his principles into practice mattered more than being reversed.[116]

Wythe's Death & Slavery

The circumstances surrounding Wythe's death also reveal insight into his views on slavery. Most historians agree that Wythe died as a result of arsenic poisoning by his heir and great nephew, George Wythe Sweeney. At the time of his death, Wythe had completely eliminated all ties to the institution of slavery from his personal life.[117] He also had incorporated into practice his philosophical teachings about the equality of blacks.[118]

The choices Wythe made concerning his estate and his free black servants may have influenced the circumstances surrounding the Chancellor's poisoning. In early 1806, Wythe changed his will to provide for a greater portion of his estate to go to Michael Brown, his freed student.[119] Wythe also left parts of his estate to Lydia Broadnax and Benjamin.[120] Specifically, Wythe requested that money from his estate be used to, "support [his] freed woman Lydia Broadnax, and [his] freed man Benjamin, and [his] freed boy Michael Brown."[121] In the event that Lydia and Benjamin died, their portion would go completely to Michael Brown.[122] This inevitably took some of the inheritance away from Wythe's other heir, Sweeney.[123] There have been many reasons offered why Sweeney poisoned Wythe and the members of his household.[124] Some authors suggest that it resulted from Wythe's choice to publicly display his belief that freed persons of color should be treated equally to white persons.[125] At the time of his death, Wythe appears to have been the only southern antebellum founder to believe in the full humanity of the Negro race and the only judge to attempt to judicially undermine slavery.[126]

Wythe as Teacher: The Influence of His Anti-Slavery Views

Wythe's views on morality and slavery also influenced his students.[127] While being taught by Wythe, Peter Carr wrote to Jefferson that Wythe "adds advice and lessons of morality, which are not pleasing and instructive now, but will be (I hope) of real utility in the future."[128]These lessons of morality likely included the topic of slavery.[129] Thomas Jefferson's most quoted statement about Wythe being "unequivocal" on the issue of slavery, was written in the context of Wythe's teaching influence.[130] In 1785, Jefferson wrote Richard Price that because of Wythe's influence, "the future decision on this important question would be great, perhaps decisive."[131] The men who studied under Wythe likely emerged from his tutelage with at least a theoretical opposition to slavery.[132] Even Jefferson, who may have not have practiced his beliefs, asserted that the system of slavery was inconsistent with the American experiment,[133] and he fought for emancipation during his early time in the Virginia legislature.[134]

Other student examples demonstrate that Wythe's teaching can be credited for the foundation of anti-slavery views. One of Wythe's pupils, John Minor III, entered two bills into the Virginia legislature providing for gradual emancipation and freedom for slaves.[135] John Marshall argued Pleasants v. Pleasants in front of the Virginia Court of Appeals, successfully freeing hundreds of slaves.[136] St. George Tucker, a student of Wythe's who became William & Mary's second law professor after Wythe's departure in 1789, became very outspoken on the issue of slavery as expressed in his 1796 pamphlet, A Dissertation on Slavery with a Proposal for the Gradual Abolition of it, in the State of Virginia, and in his commentaries on Blackstone.[137] Tucker considered slavery both morally and logically inconsistent with Virginia's Declaration of Rights.[138]

Perhaps Wythe influenced Richard Randolph, (St. George Tucker's stepson) another of Wythe's students, most on the issue of slavery.[139] In his will, Randolph freed all of his slaves at his death.[140] Along with their freedom, Randolph provided that his slaves would also be given land.[141] Randolph made Wythe the executor of his will, and wrote that Wythe was "the most virtuous and incorruptible of mankind and his greatest benefactor."[142] Randolph explicitly declared that the provisions of his will concerning the slaves were drafted "to make retribution."[143] Unfortunately, due to legal issues with the will, Randolph's wishes for his slaves did not come to fruition until much later.[144]

Few of Wythe's students, however, went as far as their teacher to free their slaves or fight to end slavery. Others, including Jefferson, Henry Clay, and St. George Tucker, continued to profit under the system of slavery.[145] Jefferson, despite his eloquent statements opposing slavery, never tried to end slavery.[146] Clay, though perhaps influenced by Wythe's anti-slavery beliefs, never followed Wythe's example in his public career.[147] Tucker's view that slavery was morally and logically inconsistent with Virginia's Declaration of Rights did not provoke him to agree with Wythe's assertion in Hudgins v. Wrights that all men were created equal.[148] Additionally, both Tucker and Jefferson strayed from the idea of complete abolition.[149] Unlike Wythe, for Tucker and Jefferson, free slaves equaled migrated slaves.[150] But, even those who criticize Wythe's influence as shallow or minimal still recognize that he had some effect on his student's beliefs about slavery.[151] That they did not put their anti-slavery views in practice ought not take away from the influence — at least intellectually — that Wythe had on all who were fortunate to have studied under him.

See also

- Anti-Slavery Petition of 1795

- Complaint regarding the estate of Frances Wythe

- "George Wythe's Gift"

- Hudgins v. Wrights

- Memoir of the Life of William Wirt

- "Memoranda Concerning the Death of Chancellor Wythe"

- Pleasants v. Pleasants

References

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Richard Price, 7 August 1785, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 8, 25 February-31 October 1785, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953), 356–357.

- ↑ Joyce Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 74; Alonzo Thomas Dill, George Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, ed. Edward M. Riley (Williamsburg: Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission, 1979), 4-5, Thomas Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," in The History of Legal Education in the United States, ed. Steve Sheppard (Pasadena: Salem, Press, Inc., 1999), 1:140.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 74; Dill, George Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, 4-5.

- ↑ Dill, George Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, 5.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ William Clarkin, Serene Patriot (Albany: Alan Publications, 1970), 3; Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," 1:140.

- ↑ John Bailey, Jefferson's Second Father (Sydney: Momentum Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd, 2013), 5.

- ↑ Dill, George Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, 5.

- ↑ Indenture of George Wythe, May 3, 1748, Deeds, Wills, Etc., 1736-1753, 282, Elizabeth City County Records. Cf. entry of that date, Order Book, 1747-1755, 33. Cited in William Edwin Hemphill, "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia" (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 1937), 49.

- ↑ H.R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia (Richmond, VA: The Virginia State Library, 1931), 1:70-71. It is unclear why Charles was put in jail or how long he worked in the lead mines. However, it is possible that Charles was the same slave freed by Wythe in 1788. Mary A. Stephenson, George Wythe House Historical Report, Block 21 (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, 1952).

- ↑ Clarkin, Serene Patriot, 9.

- ↑ "An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves." 11 Henning Statute's at Large 39 (May 1782). Private manumission laws were necessary for any future abolition in the South. Winthrop D. Jordan, White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), 347. Prior to this law, private manumission was forbidden in Virginia. Robert M. Cover, Justice Accused: Antislavery and the Judicial Process, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975) 67.

- ↑ Stephenson, George Wythe House Historical Report.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Lyon G. Tyler, "George Wythe's Gift," William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 12, no. 2 (October 1902), 125-126.

- ↑ Lyon G. Tyler, "Will of Richard Taliaferro," William and Mary Quarterly Historical Magazine 12, no. 2 (October 1903), 124-125; Robert B. Kirtland, George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge (New York: Garland, 1986), 140.

- ↑ Tyler, "Will of Richard Taliaferro," 124-125.

- ↑ Stephenson, George Wythe House Historical Report (citing the 1787-1788 York County records).

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 141; Holt, Wythe, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," Alabama Law Review 58, no. 5 (2007): 1026 (stating that Wythe had seventeen slaves total in 1784 and that he transferred thirteen of those slaves after his wife's death); Bailey, Jefferson's Second Father, 195 (stating that the total number of transferred slaves was sixteen).

- ↑ John Nierson, Complaint Regarding the Estate of Frances Wythe c. 1793. Norfolk County Court Records. Library of Virginia.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 85.

- ↑ George Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, 31 December 1781, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1952), 6: 144-145.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The Proceedings of the Convention of Delegates (Richmond, VA: Richie, Trueheart and Du-Val, 1816), 99-100. Others have cited that Neptune was imprisoned because of service to Lord Dunmore, but there is no record of him being in jail for that reason. Clarkin, Serene Patriot, 105; Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 93; Bailey, Jefferson's Second Father, 127. Instead, the record states that Neptune was imprisoned for being a runaway, and as such, he was returned to Wythe — likely back to Chesterville.

- ↑ Charles A. Goodrich, Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence (New York: William Reed, 1829) 369; Clarkin, Serene Patriot, 105.

- ↑ Bailey, Jefferson's Second Father, 172, 174.

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 303 (citing Elizabeth City County, Deeds and Wills Book).

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 123; Kirtland, George Wythe, 304.

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 304.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 304; Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 123.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 123.

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 10.

- ↑ Imogene E. Brown, American Aristides: A Biography of George Wythe (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1981), 266-267.

- ↑ Philip D. Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake and the British Atlantic World, c.1700-1820," in Sally Hemings & Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, and Civic Culture, ed. Jan Ellen Lewis and Peter S. Onuf (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), 55-57.

- ↑ Brown, 300; Morgan, "Interracial Sex on the Chesapeake," 57.

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 163.

- ↑ Henry Clay remembered Lydia as being an "old woman" during his time in the Wythe home. Henry Clay to B.B. Minor, 3 May 1851 in Decisions of Cases in Virginia, by the High Court of Chancery, with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decision, by George Wythe, ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond, VA: J.W. Randolph, 1852), xxxvi; Brown, 299; Kirtland, George Wythe, 163 fn.13; Morgan, "Interracial Sex on the Chesapeake," 57.

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 163, fn.12; Morgan, "Interracial Sex on the Chesapeake," 57; "Memoranda Concerning the Death of Chancellor Wythe," Wythepedia, accessed December 2, 2017.

- ↑ Brown, American Aristides, 299-300; Kirtland, George Wythe, 163; Morgan, "Interracial Sex on the Chesapeake," 60, 77.

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 164; Morgan, "Interracial Sex on the Chesapeake," 57 (citing Cathy Helier, George Wythe's Slaves in Williamsburg, (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1987)).

- ↑ Kirtland, George Wythe, 163, fn.14; Morgan, "Interracial Sex on the Chesapeake," 57.

- ↑ Brown, American Aristides, 299.

- ↑ Goodrich, Lives of the Signers, 370; Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1026. There has been some speculation that Brown was either a free black child or an orphan sent to Wythe for teaching. Morgan, "Interracial Sex on the Chesapeake," 59.

- ↑ Brown, American Aristides, 300.

- ↑ "George Wythe, June 11, 1806, Last Will and Testament with Codicil," in The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1 General Correspondence 1651-1827, (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1974), images 314-319; Brown, American Aristides, 300.

- ↑ Dill, George Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, 80.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Richard Price, 7 August 1785, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ' ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton, NJ: 1950-2009), 8:357.

- ↑ Wythe to Jefferson, 144.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Jefferson to Price, Page 357; Benjamin Mathews Leigh, The Letter of Appomatox to the People of Virginia (Richmond, VA: Thomas W. White, 1832), 43; Robert McColley, Slavery and Jeffersonian Virginia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1964), 136.

- ↑ Bailey, Jefferson's Second Father, 42, 146.

- ↑ Leigh, The Letter to Appomatox, 43.

- ↑ Clarkin, Serene Patriot, 188-189; Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1026.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 132.

- ↑ John P. Kennedy, Memoirs of the Life of William Wirt, rev. ed. (Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea, 1850), 1:141-142.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ William Munford to John Coalter, 22 July 1791, Tucker Papers (I), Special Collections Research Center, SWEM Library, College of William and Mary.

- ↑ Goodrich, Lives of the Signers, 370; Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1026.

- ↑ Leigh, The Letter to Appomatox, 43.

- ↑ Melvin Patrick Ely, Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from 1790s through the Civil War, (New York: A. Knoph, 2004) 24.

- ↑ Melvin Patrick Ely, "Richard and Judith Randolph, St. George Tucker, George Wythe, Syphax Brown, and Hercules White: Racial Equality and the Snares of Prejudice," in Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation, ed. Alfred F. Young, Gary B. Nash, and Ray Raphael (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011) 328.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1794), 199-201; Bailey, Jefferson's Second Father, 146-147.

- ↑ Leigh, The Letter to Appomatox, 43.

- ↑ Jordan, White Over Black, 456-457.

- ↑ Howell v. Netherland, Jefferson 90, April 1770, in Judicial Cases Concerning American Slavery and the Negro (New York: Octagon Books, Inc., 1968), 1:90.

- ↑ Howell v. Netherland, 90; Bailey, Jefferson's Second Father, 81.

- ↑ Howell v. Netherland, 91.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 93.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 96; Brown, American Aristides, 188-189; [insert a link to the completed revision in this footnote].

- ↑ Cover, Justice Accused, 52; Eva Sheppard Wolf, Race and Liberty in the New Nation: Emancipation in Virginia from the Revolution to Nat Turner's Rebellion (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), 4.

- ↑ Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 199; Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1027.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, "Autobiography, 1743-1790," in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1892), 1:68.

- ↑ Brown, American Aristides, 189; Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1027.

- ↑ McColley, Slavery and Jeffersonian Virginia, 124; Brown, American Aristides, 189.

- ↑ Brown, American Aristides, 189.

- ↑ Terry L. Meyers, "Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary," William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal 21, no. 4 (2013): 1254-56.

- ↑ "An Act to Ameliorate the Present Condition of Slaves, and Give Freedom to those Born After the Passing of the Act," Library of Virginia, Legislative Petitions microfilm, Reel 233, Box 294, Folder 5.

- ↑ Ibid., 1

- ↑ There is no record that the petition ever made it to the floor of the House of Delegates.

- ↑ Turpin v. Turpin (1791), in Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond, VA: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 137 (hereafter cited as Wythe); Fowler v. Saunders (1798), Wythe, 322; John T. Noonan Jr., Persons and Masks of the Law: Cardoza, Holmes, Jefferson, and Wythe as Makers of the Masks, (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1976) 55-56.

- ↑ Turpin, Wythe at 140; Fowler, Wythe at 327.

- ↑ Turpin, Wythe at 140 (stating, "[a]s the law is now, and always has been, a bequest of slaves transfers the property of them in the same manner as if they were chatels").

- ↑ Noonan, Persons and Masks of the Law, 58.

- ↑ Hudgins v. Wrights, 11 Va. (1 Hen. & Mun.) 134 (1806); Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1027-1028.

- ↑ Hudgins, 12 Va. (1 Hen & Mun.) 134 (1806); Virginia: In the High Court of Chancery, March 16, 1798, Between Robert Pleasants, son and heir of John Pleasants ... and Mary Logan (Richmond, VA: 1800?); Pleasants v. Pleasants, 2 Call 319 (1799) (hereafter cited as Pleasants v. Logan).

- ↑ Hudgins, 12 Va. (1 Hen & Mun.) at 140; Pleasants, 2 Call at 344, 346; Cover, Justice Accused, 71; Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1028; William Fernandez Hardin, "This Unpleasant Business: Slavery, Law, and the Pleasants Family in Post-Revolutionary Virginia," in Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 2017.

- ↑ Pleasants, 2 Call at 334; Pleasants v. Pleasants (Chancery Opinion).

- ↑ Pleasants, 2 Call at 353; Pleasants v. Logan, at 1-2.

- ↑ Pleasants, 2 Call at 354; Pleasants v. Logan, at 2.

- ↑ Cover, Justice Accused, 69.

- ↑ Pleasants v. Logan, at 2; Hardin, "This Unfinished Business," 224.

- ↑ Pleasants v. Logan, at 2.

- ↑ Hardin, "This Unpleasant Business," 224.

- ↑ Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1029.

- ↑ Pleasants v. Logan, at 3; Cover, Justice Accused, 71; Peter Charles Hoffer, The Law's Conscience: Equitable Constitutionalism in America, (Chapel Hill; The University of North Carolina Press, 1990) 113; Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1031.

- ↑ Cover, Justice Accused, 69; Morgan. "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 58; Hardin, "This Unpleasant Business," 225.

- ↑ Cover, Justice Accused, 71; Hardin, "This Unpleasant Business," 227-28.

- ↑ Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1033.

- ↑ Cover, Justice Accused, 51.

- ↑ Hudgins, 11 Va. (1 Hen. & Mun.), at 134.

- ↑ Cover, Justice Accused, 51.

- ↑ Cover, 51; Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1032.

- ↑ Hudgins, 11 Va. (1 Hen. & Mun.), at 141.

- ↑ Hudgins, at 141; Ely, Israel on the Appomattox, 23-24.

- ↑ Hudgins, 11 Va. (1 Hen & Mun), at 134; Brown, American Aristides, 191; Wolf, Race and Liberty in the New Nation, 148.

- ↑ Hudgins, 11 Va. (1 Hen. & Mun.), at 139; Wolf, Race and Liberty in the New Nation, 148.

- ↑ Hudgins, 11 Va. (1 Hen. & Mun.), at 144.

- ↑ Hudgins, at 144.

- ↑ Hudgins, at 139, 141.

- ↑ Brown, American Aristides, 191. Some authors find Wythe's decision in Hudgins to be an outlier or a mere gesture made at the end of the Chancellor's life. Noonan, Persons and Masks of the Law, 56-57 (for the argument that the Hudgins decision did not change Wythe's views that the law determined who could be considered property); Ely, "Racial Equality and the Snares of Prejudice," 327 (for the argument that Wythe's decision in Hudgins was a mere gesture that could only happen at the end of one's life). But, these authors do not take into account that in both Pleasants and Hudgins, Wythe went further than any southern antebellum judge to attack the institution of slavery. Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1033.

- ↑ Henry Clay acknowledges that before Wythe devised his estate, he had emancipated all his slaves. Henry Clay to B.B. Minor, Decisions of Cases in Virginia, xxxv.

- ↑ Julian P. Boyd, "The Murder of George Wythe," in The Murder of George Wythe: Two Essays (Williamsburg, VA: Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1955), 24.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 135.

- ↑ Wythe, Last Will and Testament.

- ↑ Wythe, Last Will and Testament; Goodrich, Lives of the Signers, 370.

- ↑ Wythe, Last Will and Testament.

- ↑ Wythe, Last Will and Testament.

- ↑ "The Murder of George Wythe," Wythepedia, accessed December 2, 2017.

- ↑ Ely, "Racial Equality and the Snares of Prejudice," 328; Holt, "George Wythe," 1038.

- ↑ Holt, "George Wythe: Early Modern Judge," 1038.

- ↑ Jefferson to Price, 357; Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," 156.

- ↑ Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 18 April 1787

- ↑ Wolf, Race and Liberty in the New Nation, 104.

- ↑ Jefferson to Price, 357.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ely, Israel on the Appomattox, 23.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 74; McColley, Slavery and Jeffersonian Virginia, 125 (for support that Jefferson's views on slavery were influenced by his pre-revolution education with George Wythe).

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 74.

- ↑ Clarkin, Serene Patriot, 157.

- ↑ Hardin, "This Unpleasant Business", 211.

- ↑ McColley, Slavery and Jeffersonian Virginia, 132; Cover, Justice Accused, 53.

- ↑ Cover, Justice Accused, 50; Ely, "Racial Equality and the Snares of Prejudice," 323-327 (for a complete summary of Tucker's views on slavery).

- ↑ Ely, Israel on the Appomattox, 22, 32-33; Ely, "Racial Equality and the Snares of Prejudice," 323, 327.

- ↑ Clarkin, Serene Patriot, 158, 198.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Richard Randolph's Will, Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, Centennial Anniversary of the Pennsylvania Society, for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, the Relief of Free Negroes, Unlawfully Held in Bondage And for Improving the Condition of the African Race (Philadelphia: Grant, Faires & Rodgers, 1875), 79-82; Ely, Israel on the Appomattox, 24 (stating that, "Richard Randolph thus took as his hero [George Wythe] a man who carried the doctrine of human equality considerably further than Randolph's greatest benefactor, St. George Tucker").

- ↑ Richard Randolph's Will, 79-82; Clarkin, Serene Patriot, 198-99.

- ↑ Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," 157.

- ↑ Noonan, Persons and Masks of Law, 60.

- ↑ Paul Finkelman, "Thomas Jefferson and Anti-Slavery: The Myth Goes On," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 102, no. 2 (1994): 211-212.

- ↑ Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 125-27.

- ↑ Hudgins, 11 Va. (1 Hen. & Mun.), at 139-141; Cover, Justice Accused, 51.

- ↑ Wolf, Race and Liberty in the New Nation, 105.

- ↑ Jefferson's gradual abolition plan included measures to migrate the slaves. Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg, 74; Wolf, Race and Liberty in the New Nation, 105.

- ↑ Noonan, Persons and Masks of Law, 60.