Difference between revisions of "Love against Donelson"

(→External links) |

Dbthompson (talk | contribs) (→Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library) |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

| − | Upon his death, a copy of this pamphlet which had belonged to Wythe was [[Last Will and Testament|bequeathed with his books]] to [[Thomas Jefferson]]. Jefferson had the pamphlet bound into a volume with seven of Wythe's other Chancery decisions which were published as supplements.<ref>"Six tracts originally bound together in calf for Jefferson by Milligan on June 30, 1807 (cost $1.00). Rebound in Buckram for the Library of Congress." E. Millicent Sowerby, comp., [http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015033648109?urlappend=%3Bseq=222 ''Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson''] (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1953), 2:208.</ref> Subsequently, the volume became part of the collection at the Library of Congress, titled on the spine: ''Wythe's Reports. Supplement. Virginia. 1796-99'' (despite this case taking place in 1801).<ref>[http://lccn.loc.gov/22003059 Library of Congress catalog record.] This volume contains pamphlets for: ''[[Case upon the Statute for Distribution]]'' (1796); ''[[Field v. Harrison]]'' (1794); ''[[Fowler v. Saunders]]'' and ''[[Goodall v. Bullock]]'' (1798, together in the same pamphlet); ''[[Wilkins v. Taylor]]'' (1799); ''[[Yates v. Salle]]'' (1792); and ''[[Love v. Donelson]]'' (1801). See also: ''[[Aylett v. Aylett]]'' (1793), and ''[[Overton v. Ross]]'' (1803).</ref> The pamphlet for ''Love against Donelson'' has a handwritten notation, "no. 7," on the first page. | + | Upon his death, a copy of this pamphlet which had belonged to Wythe was [[Last Will and Testament|bequeathed with his books]] to [[Thomas Jefferson]]. Jefferson had the pamphlet bound into a volume with seven of Wythe's other Chancery decisions which were published as supplements.<ref>"Six tracts originally bound together in calf for Jefferson by Milligan on June 30, 1807 (cost $1.00). Rebound in Buckram for the Library of Congress." E. Millicent Sowerby, comp., [http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015033648109?urlappend=%3Bseq=222 ''Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson''] (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1953), [http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015033648109;view=1up;seq=223 [2:208]].</ref> Subsequently, the volume became part of the collection at the Library of Congress, titled on the spine: ''Wythe's Reports. Supplement. Virginia. 1796-99'' (despite this case taking place in 1801).<ref>[http://lccn.loc.gov/22003059 Library of Congress catalog record.] This volume contains pamphlets for: ''[[Case upon the Statute for Distribution]]'' (1796); ''[[Field v. Harrison]]'' (1794); ''[[Fowler v. Saunders]]'' and ''[[Goodall v. Bullock]]'' (1798, together in the same pamphlet); ''[[Wilkins v. Taylor]]'' (1799); ''[[Yates v. Salle]]'' (1792); and ''[[Love v. Donelson]]'' (1801). See also: ''[[Aylett v. Aylett]]'' (1793), and ''[[Overton v. Ross]]'' (1803).</ref> The pamphlet for ''Love against Donelson'' has a handwritten notation, "no. 7," on the first page. |

Several pages of the pamphlet contain manuscript corrections by Wythe in his hand,<ref>"Manuscript notes by Wythe." [http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015033648109?urlappend=%3Bseq=223 Sowerby, 2:209.]</ref> including a footnote in Greek, apparently scraped off and corrected to 'Κάλχας Θεστορίδης οἰωνοπόλων': "[[wikipedia:Calchas|Calchas]], son of Thestor, far the best of augurs" (bird-diviners).<ref>Calchas was the prophet of Troy. Homer, [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0133%3Abook%3D1%3Acard%3D68 ''Iliad'' 1.69.]</ref> On another page Wythe made a notation in the margin referring to Taylor's ''[[Elements of the Civil Law]]'' (1769). | Several pages of the pamphlet contain manuscript corrections by Wythe in his hand,<ref>"Manuscript notes by Wythe." [http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015033648109?urlappend=%3Bseq=223 Sowerby, 2:209.]</ref> including a footnote in Greek, apparently scraped off and corrected to 'Κάλχας Θεστορίδης οἰωνοπόλων': "[[wikipedia:Calchas|Calchas]], son of Thestor, far the best of augurs" (bird-diviners).<ref>Calchas was the prophet of Troy. Homer, [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0133%3Abook%3D1%3Acard%3D68 ''Iliad'' 1.69.]</ref> On another page Wythe made a notation in the margin referring to Taylor's ''[[Elements of the Civil Law]]'' (1769). | ||

Revision as of 13:13, 20 January 2016

by George Wythe

| Love, against Donelson and Hodgson | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | George Wythe | |

| Published | n.p. (Richmond, VA?): n.p. (Thomas Nicolson?) | |

| Date | n.d. (1801?) | |

| Language | English | |

| Pages | 34 | |

| Desc. | 8vo (21 cm.) | |

Love, against Donelson and Hodgson[1] is a published opinion by George Wythe, for the case Love v. Donelson in Virginia's High Court of Chancery. Wythe states that the case took place in the "first year of the nineteenth centurie," so Love against Donelson must have been published sometime between 1801 and the year of Wythe's death, in 1806.[2] Wythe's mention of [Benjamin] Watkins Leigh being "one of William and Mary's ornaments" (p. 32n) suggests the pamphlet was published no later than 1802. Leigh graduated from the College in 1802.[3] The report was almost certainly printed by Thomas Nicolson of Richmond, Virginia, who had published Wythe's Reports in 1795, and at least seven other supplements for Wythe, in 1796 and after.[4]

Love v. Donelson was not reported in the second edition of Wythe's Reports, in 1852.[5][6]

Contents

- 1 Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

- 2 Document text, c. 1801

- 2.1 Page 1

- 2.2 Page 2

- 2.3 Page 3

- 2.4 Page 4

- 2.5 Page 5

- 2.6 Page 6

- 2.7 Page 7

- 2.8 Page 8

- 2.9 Page 9

- 2.10 Page 10

- 2.11 Page 11

- 2.12 Page 12

- 2.13 Page 13

- 2.14 Page 14

- 2.15 Page 15

- 2.16 Page 16

- 2.17 Page 17

- 2.18 Page 18

- 2.19 Page 19

- 2.20 Page 20

- 2.21 Page 21

- 2.22 Page 22

- 2.23 Page 23

- 2.24 Page 24

- 2.25 Page 25

- 2.26 Page 26

- 2.27 Page 27

- 2.28 Page 28

- 2.29 Page 29

- 2.30 Page 30

- 2.31 Page 31

- 2.32 Page 32

- 2.33 Page 33

- 2.34 Page 34

- 3 See also

- 4 References

- 5 External links

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

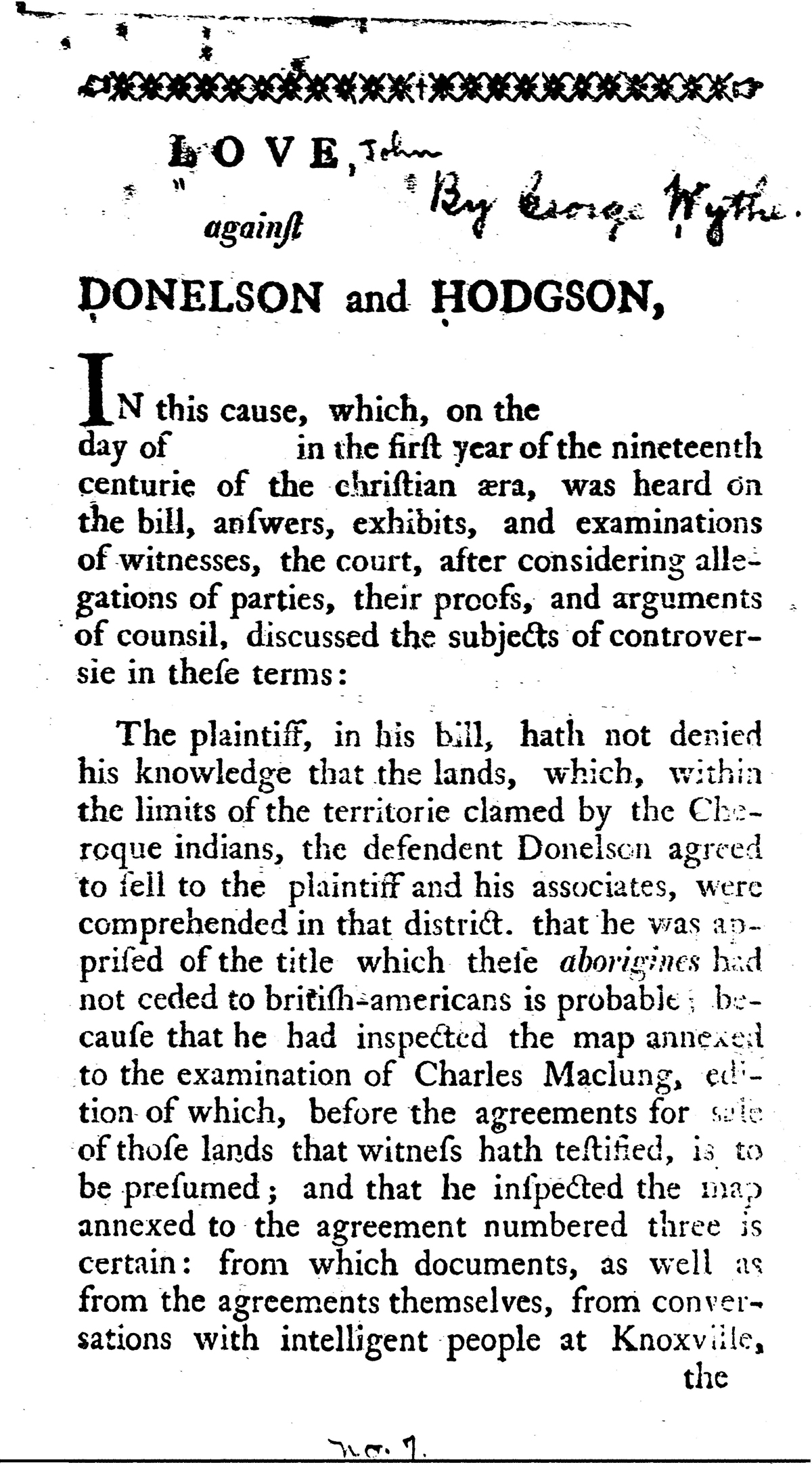

Upon his death, a copy of this pamphlet which had belonged to Wythe was bequeathed with his books to Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had the pamphlet bound into a volume with seven of Wythe's other Chancery decisions which were published as supplements.[7] Subsequently, the volume became part of the collection at the Library of Congress, titled on the spine: Wythe's Reports. Supplement. Virginia. 1796-99 (despite this case taking place in 1801).[8] The pamphlet for Love against Donelson has a handwritten notation, "no. 7," on the first page.

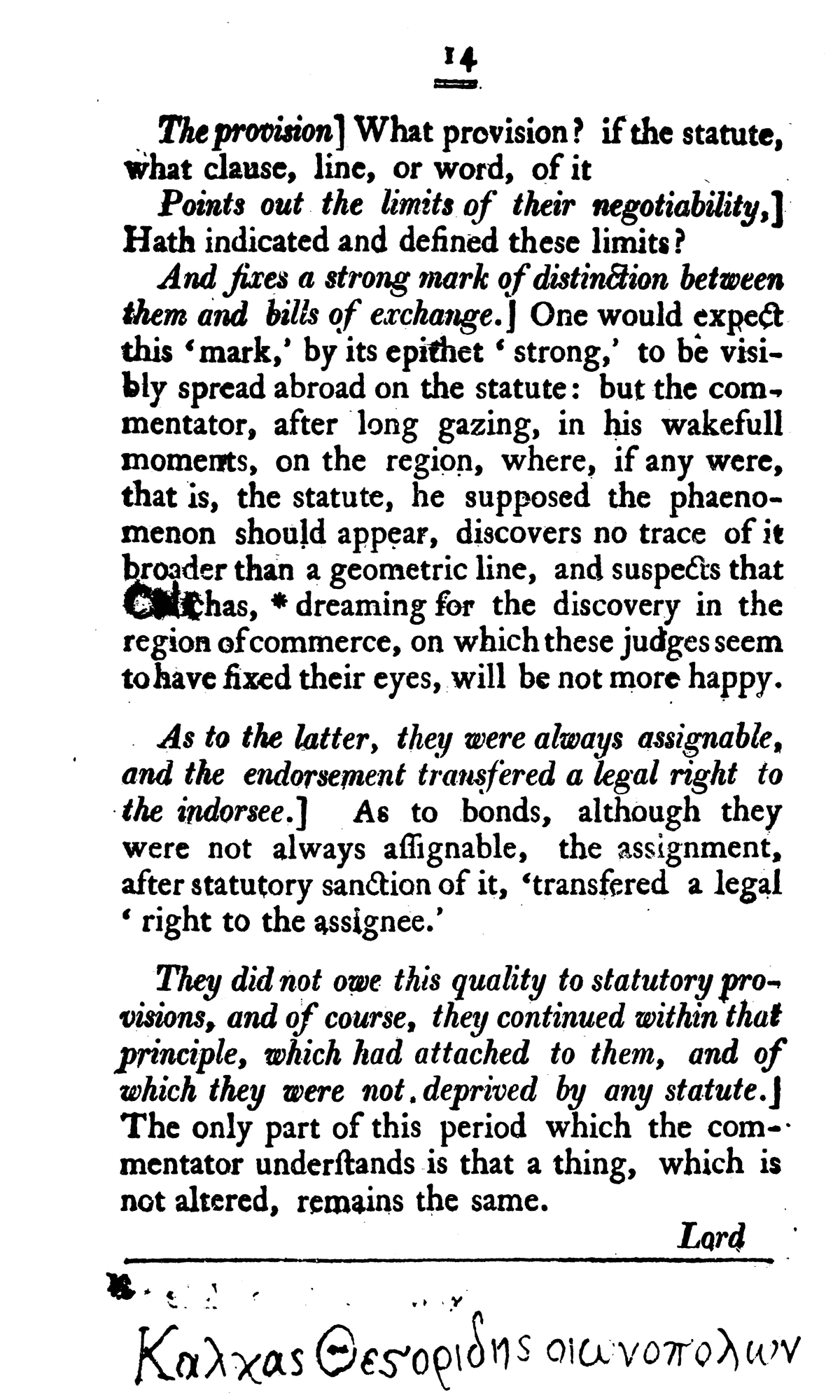

Several pages of the pamphlet contain manuscript corrections by Wythe in his hand,[9] including a footnote in Greek, apparently scraped off and corrected to 'Κάλχας Θεστορίδης οἰωνοπόλων': "Calchas, son of Thestor, far the best of augurs" (bird-diviners).[10] On another page Wythe made a notation in the margin referring to Taylor's Elements of the Civil Law (1769).

Document text, c. 1801

Page 1

LOVE,

against

DONELSON and HODGSON,

Page one from Wythe's pamphlet, Love, Against Donelson and Hodgson (1801?). Copy at the Library of Congress.

Page one from Wythe's pamphlet, Love, Against Donelson and Hodgson (1801?). Copy at the Library of Congress.IN this cause, which, on the day of in the first year of the nineteenth centurie of the christian æra, was heard on the bill, answers, exhibits, and examinations of witnesses, the court, after considering allegations of parties, their proofs, and arguments of counsil, discussed the subjects of controversie in these terms:

The plaintiff, in his bill, hath not denied his knowledge of that lands, which, within the limits of the territorie clamed by the Cheroque indians, the defendent Donelson agreed to fell to the plaintiff and his associates, were comprehended in that district. that apprised of the title which these aborigines had not ceded to british-americans is probable; because that he had inspected the map annexed to the examination of Charles Maclung, edition of which, before the agreements for sale of those lands that witness hath testified, is to be presumed; and that he inspected the map annexed to the agreement numbered three is certain: from which documents, as well as from the agreements themselves, from conversations with intelligent people at Knoxville,the

Page 2

the scene of the transaction, and from the public offices, the plaintiff might have derived, and is believed to have derived, all the information which the defendent could communicate.

But he (Donelson) was, by the terms of the agreements, and of covenants in the conveyances, that he would warrant generaly, sponsor as well against indians as against all other men. so that

The defendent Donelson, if for him, in his own name, judgment had been rendered in an action upon the bond which was dischargeable in the ninety sixth year of the eighteenth centurie, would have been enjoined from obtaining the whole of the money recovered, or so much of it as is equal to the price of what lands sold by him to the plaintiff were abdicated by the british americans in the treaty between them and the indians.

Against the other defendent, to whom the bond was assigned, and in whose name judgment was entered, if he had known the origin of the debt, and especialy if he had known too that the seller of the lands for the price of which the bond was given had not a title to them, like relief would have been extended: but such knowledge was denied by that defendent in his answer, which hath not been disproved.

Ought the plaintiff, then, to be relieved against the defendent Hodgson, an unconciousassignee,

Page 3

assignee, for a valuable consideration, of the bond?

In august of the eighty ninth year of the eighteenth centurie this court delivered the following opinion:

'An obligator is not intitled to relief against the obligation in the hands of the assignee, who, having paid a valuable consideration for it without knowledge of unfairness in the sale of a negro, for payment of the price whereof the obligation was granted, and who being impowered by statute to commence and prosecute an action in his own name, had a legal right to the money acknowledged by the obligation to be due, and whose equity was not less than the obligors equity.' Chancery decisions, folio 115: where objections to the opinion are answered.

In opposition to it are these words of the supreme judicatorie of this commonwealth, in the case of Norton against Rose, reported by Washington, 2 vol' p' 254:[11] the court is of opinion, that an assignee of a bond or obligation takes the same, subject to all the equity of the obligor, conformably with which opinion a decree of the high court of chancery was reserved.

Orthodoxie of the sentence pronounced by the judges of appeal will be here examined in this commentarie; where the names of the par-ties

Page 4

ties in this case shall be put for the names of the parties in that:

Roane, j'. Upon the principles of the common law, a chose en action is not assignable, that is, the assignment does not give to the assignee a right to maintain an action in his own name.] If Love oblige himself to pay twenty thousand dollars to Donelson, or to his assignee, and Donelson assign the obligation to Hodgson for value received of him, who was neither party nor privy to the contract between the two former, and if the common law, inhibiting assignment of a chose en action, had never existed, the right of Hodgson to so much of the money as had not been paid before assignment, would have been the same as if that remainder had been, by terms of the obligation, payable immediately to himself, without pervading Donelson. for,

In the case supposed, the obligation is resolvable into this sense: I, John Love, acknowledging myself indebted twenty thousand dollars to Stockley Donelson, agree to pay them, if he order them to be paid, to William Hodgson, and the money would, after such order, that is, the assignment, have been due to tis last no less truly than it would have been due if he had been due if he had been original obligee, except that he must have discounted payments to Donelson, who would have been a mere fistula or pipe through which the obligation of Love was conveyedWhat

Page 5

What hath been said is undeniable, as the commentator ventureth to suppose. if the supposition be not rash,

Since the statute, which, giving validity to translation of such chose en action, and, for recovery therof, authorising assignees in their own names to prosecute actions, hath silenced the common law, Donelsons intervention in the transaction cannot affect the right of Hodgson, otherwise than that Love is entitled to the discounts mentioned before and to be defined hereafter.

In England, the assignee of a bond takes it charged with every species of equity which was attached to IT in the hands of the obligee.] This is intelligible and true in case of such an obligation as this:

Know all men that i John Love am held bound unto Stockely Donelson in 40000 dollars, to be paid to him, or to his assigns, for which payment i bind my representatives, as well as myself. this obligation however shall be void if, on or before the day, &c', i pay to him 20000 dollars, the price of certain lands which he hath sold to me, covenanting that he hath a title to them, and that they are unemcumbered.

If the terms of the bond do not shew or lead to inquire for what cause the money, thereby acknowledged to be due, became due, the wordsof

Page 6

of the text, 'equity attached to it in the hands of the obligee,' seem inexplicable. to attach is to take hold of something. from Stockley Donelson selling land, which was not his, to John Love, and taking an obligation for payment of the price, the deceived purchaser had a right to demand restitution of the obligation; for that, deprived of the things bought, he should retain their price, by which the evidence of the debt indicates that he was to merit them, is equity. parties would have then been in status quo they were before the bargain, or would have been after performance of it by both. of this equity, when it is expanded or inscribed on, or may be investigated from something apparent in, the instrument signifying altern obligations of the parties, may be predicated, that the equity is attached to the bond, by the words of which those obligations may be conjectured, if not discovered. the parts of the contract, for example, on the side of Stockley Donelson, that John Love shall permanently and quietly possess lands sold to him, and, on the side of John Love, that Stockley Donelson, for assurance of this benefit, shall receive an adstipulated retribution, are attached mutally, or have hold of, are connected with, each other, in whose hands soever may be the bond or writing which is evidence of the contract.

But what can be the meaning of 'equity attached' to a simple bond, obliging one topay

Page 7

pay money, for which the law supposeth him to have received value, when the cause of the contract doth not appear by the bond itself? can the obligees equity have hold of any part of, or be connected with any syllable in, the bond?

If a different principle in this country, it must grow out of the acts of assembly, which authorised the assignment of bonds.] The proposition, condemned by the court of appeals, 'grew out of,' or was a deduction from, those acts of assembly giving energy to this principle: of contending parties he, who, having an equitable title, acquireth a fair legal title also, to the thing in question, shall prevale against him who hath an equitable title only: which principle was not long ago supported by jurisprudentes to be no more disputable than the axiom, the whole is greater than its part, is supposed by geometricians to be deniable. that Hodgson, an unconscious assignee for value, hath an equitable title is admitted; the statute, authorising him to prosecute an action in his own name, gave him a legal title; and that Love hath any more than equitable title is not pretended. such reasoning as this, in the case between Norton and Rose was the 'ground' of the high court of chanceries decree, which CLARIFIED judges reprobated, one, who 'CLEARLY entertained his opinion upon the subject, pronouncing the ground of the decreeto

Page 8

to be wrong (p' 251;) another professing himself upon the whole to be CLEAR that the decree was erroneous' (p' 253;) and with them a third, 'upon the whole also concurring' (p' 254.)

The acts &c.'] Three line here might as well been any where, or no where, else.

This case depends upon the construction of the act of 1748.] Instead of this construction, which is not once attempted, we are often told what was the intention and the design of the act.

The intention of it, &c'] In these words and the rest of te paragraph we learn nothing more than what we learn by barely reading the statute itself.

It was not intended to abridge the rights of the obliger,] Before the statute, against the assignee the obligor had a right to oppose his equitable demands; why? becasue the assignee had no more than an equitable right. but after the statute, which gave a legal right to the assignee, against him, armed with two rights one equitable the other legal, could the obligor oppose his single equitable right? were not the former more potent, was not the latter more feeble; and consequently was not this adbridged? if the statute, by conclusion inevitable, 'hath abridged the right of the obligor,' bywhat

Page 9

what authority can a judge thus affirm, that 'to abridge the rights of the obligor was not intended?' he is required to exhibit the diploma constituting him explorer of the legislative intention, when legislative words have not revealed it.

Or to enlarge those of the assignee, beyond, &c] The statute, giving to the assignee one right more than he had before, namely, the right of recovering by an action prosecuted in his own name, doubled his rights, and, if a thing doubled is enlarged, and if the court of appeals will permit the legislature to know their intentions, 'to enlarge the rights of assignees was intended.'

And since it is clear, that, prior to this law, an original equity attached to the bond,] Attachment to the simple bond is denied.

Followed it into the hands of the assignee,] The passport of this equity against the obligee into the assignees hands, before the statute, was revoked by the statute; for in contradiction to what is asserted in the text, that

This law does not expressly, nor by implication destroy the principle.] Is affirmed, that the law, when it gave the legal right to the assignee, did, by necessary implication and inevitable infe-rence, '

Page 10

rence, 'destroy that principle' as it is called: because the assignees legal right by the statute, combined with his equitable right, being duplicate, triumphed over the obligors right, which was solitary.

Notes of hand are now assignable in England, and it is admitted that the assignee is discharged of any equity, which existed against the assignor, unless the note was given, for an usurious, or for a gaming consideration.] The assignee here is supposed before the statute to have been charged with, for otherwise he could not have been discharged of, 'the equity' which 'existed against the assignor.' the supposition is not true. The assignee, before the statute could not assert his own right, which was but an equitable right, and which the drawers equity therefore impeded, and could not assert the payees right, which, if he retained the note, would have been defeated by the drawers equity.

The reason of this is not that the principle attached to them as a legal consequence of their being made assignable,] To prove the reason here disallowed to be the true reason hath been attempted.

But because this rule, for commercial purposes, applied to bills of exchange, and the statute of Anne,[12] declaring notes assignable in like man-ner

Page 11

ner as bills of exchange, shewed an intention, as it was supposed, to render the former as highly negociable and as current in internal, as the latter was in external commerce.] This was intended to teach, that in England, if the words 'in like manner as bills of exchange,' had been omitted in the statute of Anne, assignees of promisory notes would have been charged with assignors equity. to prove it a single argument, better than the princippii petitio, hath not been urged. yet to disprove it shall be here essayed.

A bill of exchange is transferable or assignable, that is, he, who by bill of exchange hath a right to demand money, may pass that right, or give it currency, to others in one or another of these manners; either by writing his name under these or like words, 'pay the contents to the assignee' naming him, or by writing the assignors name, without any superscription. in both manners, the writings are called indorsements, because usualy placed on the back, in dorso, of the bill; and that indorsement which is nude is equivalent to the other, the holder there being assignee.

In the statute of Anne, the words; 'promisory notes, payable to order or bearer, may be assigned and endorsed, and action maintains thereon in like manner as inland bills of exchange,' mean neither more nor less than these words: 'promisory notes, payable to or-der,

Page 12

der, or bearer, may be assigned and endorsed by the assignor, writing his name under these or like words, 'pay the contents to the 'assignee,' or by writing or endorsing the assignors name, not superscribed, or in blank as it is called, and action maintained thereon.' this parap^hrase, the rectitude of which no man of candor will dare to deny, clearly proves that the MANNER of authorising the passage, the NEGOTIABILITY, or the CURRENCY, changes not the thing to which is given passage, NEGOTIABILITY, or CURRENCY, whether it be by an indorsement on the same or writen on a separate paper, or by any other MANNER.

If this be correct, and if the words 'in like manner as bills of exchange' had not been in the statute of Anne, promisory notes would have been negotiable, or in the phrase of the text as highly negotiable, as they nor are; perhaps more negotiable, because the statute which prescribed the manner of negotiation, that is by indorsement, must be persued, whereas, if the words, in like manner as inland bills of exchange' had been omited, promisory notes might have been negotiated, or assigned, in some other MANNER.

The learned judges doctrine, therefore, is unsound and bonds made assignable as negotiable, in this country, as bills of exchange andpromisory

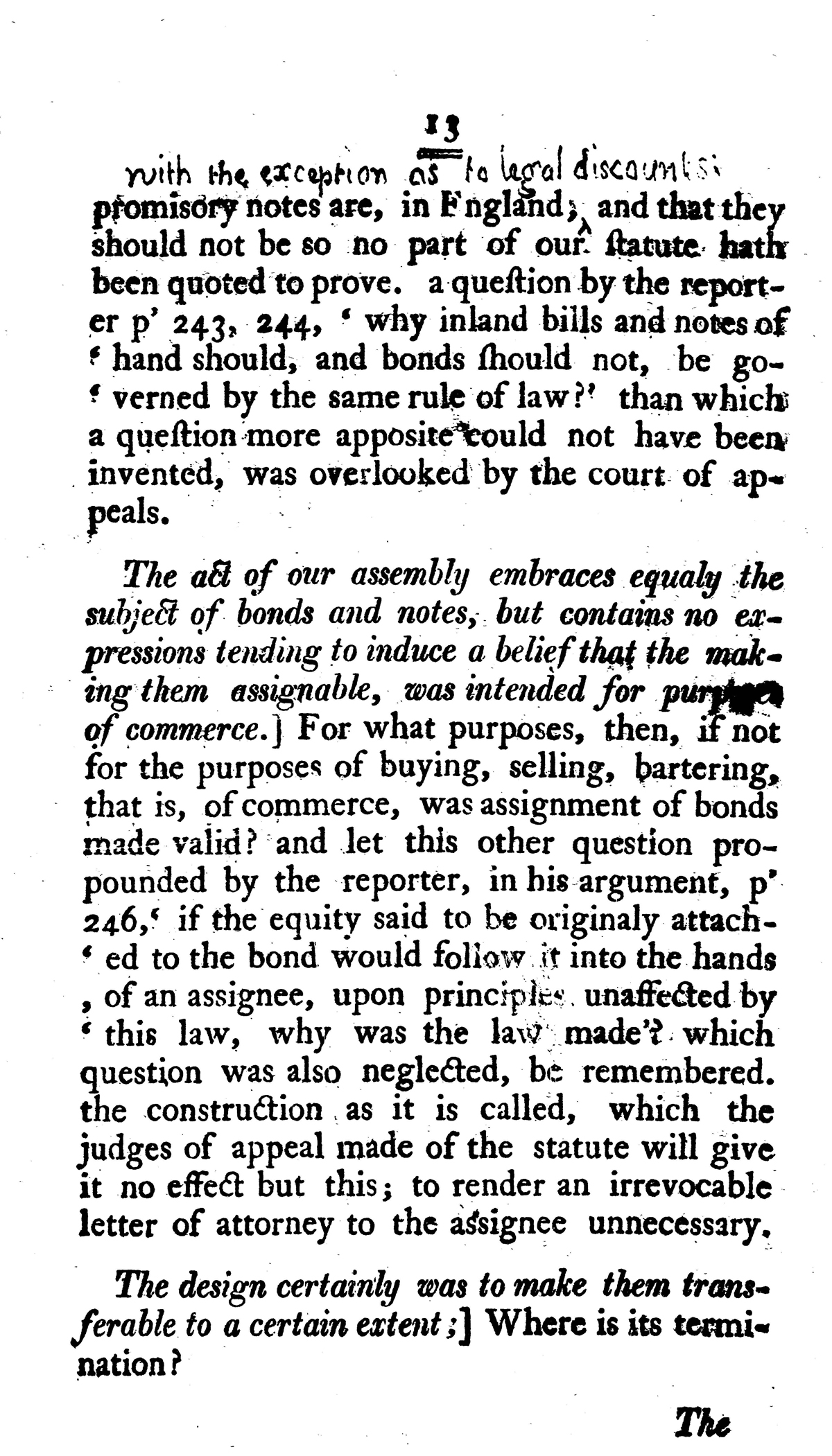

Page 13

promisory notes are, in England,^with the exception as to legal discounts; and that they should not be so no part of the statute hath been quoted to prove. a question by the reporter p' 243, 244, 'why inland bills and noted of hand should, and bonds should not, be governed by the same rule of law?' than which a question more apposite could not have been invented, was overlooked by the court of appeals.

The act of our assembly embraces equaly the subject of bonds and notes, but contains no expressions tending to induce a belief that the making them assignable, was intended for purposes of commerce.] For what purposes, then, if not for the purposes of buying, selling, bartering, that is, of commerce, was assignment of bonds made valid? and let this other question propounded by the reports, in his argument, p' 246, 'if the equity said to be originaly attached to the bond would follow it into the hands of an assignee, upon principles unaffected by this law, why was the law made?' which question was also neglected, be remembered. the construction as it is called, which the judges of appeal made of the statute will give it no effect but this; to render an irrevocable letter of attorney to the assignee unnecessary.

The design certainly was to make them transferable to a certain extent;] Where is its termination?The

Page 14

The provision] What provision? if the statute, what clause, line, or word, of it

Points out the limits of their negotiability,] Hath indicated and defined these limits?

And fixes a strong mark of distinction between them and bills of exchange.] One would expect this 'mark,' by its epithet 'strong,' to be visibly spread abroad on the statute: but the commentator, after long gazing, in his wakefull moments, on the region, where, if any where, that is, the statute, he supposed the phaenomenon should appear, discovers no trace of it broader than a geometric line, and suspects that Calchas,* dreaming for the discovery in the region of commerce, on which these judges seem to have fixed their eyes, will be not more happy.

As to the latter, they were always assignable, and the endorsement transfered a legal right to the indorsee.] As to bonds, although they were not always assignable, the assignment, after statutory sanction of it, 'transfered a legal right to the assignee.'

They did not owe this quality to statutory provisions, and of course, they continued within that principle, which had attached to them, and of which they were not, deprived by any statute.] The only part of this period which the commentator understands is that a thing, which is not altered, remains the same.Lord

* Κάλχας Θεστορίδης οἰωνοπόλων

Page 15

Lord Mansfield lays it down, in the case of Peacock and Rhodes, Dougl' 636,[13] that the holder of a bill of exchange, or promisory note, is not to be considered in the light of an assignee of the payee.] This only affirms assignee of a promissory note to be in a better state than payee; because the assignor, by his endorsement, is bound as well to the drawer, to discharge the note.

An assignee must take the thing assig^ned, subject to all the equity to which the original party was subject: if this rule applied to bills and promissory notes it would stop their currency.] Mansfields reasoning, if it be not misunderstood, is, the currencies by indorsation of bills of exchange, and by assignment or indorsation of promisory notes, to one of which customary law and to the other statutory law gave sanction, would be interrupted, if the rule, that an assignee 'must take the thing assigned subject to all the equity to which the original party was subject,' applied to those commercial media. now to what inference doth analogie point? planely this: the rule applies not to syngraphs, instruments, to which, signifying the holders credits, customary or statutory law hath attributed NEGOTIABILITY OR CURRENCY. and bonds being in that predicament, the consectarie is, the rule doth apply, not to bonds assigned but, only to instruments which have no legal CURRENCY, OR NEGOTIABILITY.So

Page 16

So in Cuninghams laws, &c.] Unimportant.

And we are informed by Domat, &c.] The same to the end of the paragraph.

The whole of what is contained in the last paragraph of 249 hath been examined already.

With respect to the proviso in the act of 1748 it cantemplates legal discounts only.] Admitted. why then was it extended to discounts equitable?

The words 'the plaintiff shall allow all discounts which the defendent can prove, were meant to extend those discounts beyond the credits which might be endorsed on the bond,] The words extend undoubtedly to credits, that is, legal credits, which, although they might not be endorsed on the bond, he can prove otherwise.

And the latter words, 'before notice of such assignment was given to the defendent,' were meant to restrain the discounts to such as existed prior to notice of the assignment.] By this we learn that the words 'before' and 'prior' have the same meaning.

This* enlarging and restraining proviso wasnecessary,]

* The commentator doth not recollect to have read or heard of an enlarging proviso before. a proviso, on the contrary, diminisheth. here it was intended to prevent the assignee from recovering more of the money by the bond acknowledged to be due than what remained unpaid. But it was, lest the law should be misunderstood, abundantly cautelous; because in an action upon the bond the defendent might have pleaded paiment, if the proviso had not been inserted. acts of 1748, cap' 5 of the edit' in 1769, cap' 76, § 21 of the edit' in 1794.

Page 17

necessary,] Here aptly may be defined the discounts which the assignee shall allow. by the statute

'The assignment shall be valid, and the assignee may thereupon maintain an action in his own name, provided he shall allow all just discounts, not only against himself but, against the assignor, before notice of the assignment was given to the defendent.'

What did the proviso enlarge? in p' 248, l' 33, we were told, 'the statute was not intended to enlarge the rights of the assignee;' that the assignees rights were enlarged is clearly proved by the act. the proviso did not enlarge the rights of the assignor. It did not leave him in a better state than that in which he would have been, if the bond had not been assigned. what state was that? answer: 'when any suit shall be commenced and prosecuted for any debt due by judgment, bond, bill, or otherwise, the defendent shall have liberty, upon trial thereof, to make all the discounts he can against such debt; and upon proof thereof the same shall be allowed in court.' stat.' 1748, cap. 27 of edit' in 1769,* § 6.what

* This section, not known by the commentator to have been repealed, is supposed to be in force, although it is not in the act published in the collection of 1794, which, as its title importeth, was intended for a pandect of the statutes, or to contain all of them which were in force.

Page 18

what discounts shall be allowed in court? those which 'he can make upon TRIAL.' trial of what? 'suit prosecuted for a debt due by bond,' &c.' the discount being that which can be 'proved upon trial' must be a legal discount, and as is admitted by the judge, p' 250 l' 4, 'LEGAL DISOUNTS ONLY. The proviso did not leave the obligor in so good a state as that in which he would have been, if the bond had not been assigned. he might, resorting to the court of equity, be relieved, if he had equity, against the obligee; but repulsion must be his fate asking equity against the assignee who hath equity likewise.

In order to express clearly the meaning of the legislature;] The legisiatures meaning is expressed so clearly by the words of the statute, t}lat to mistake it seemed to the commentator a difficulty, and the only difficulty.

But neither the proviso nor any other part of this act was intended to extend to equitable discounts,] Why then was it extended to equitable discounts, as they are called, by the court of appeals?

Or to abridge equitable discounts, which were not in the contemplation of the legislature.] This is nothing but a repetition of part of the last paragraph of p,' 248.

The inconvenience, which it is apprehended willresult

Page 19

result from rejecting the application of the principle contended for, is certainly not real, or if it be, it was not so considered by the legislature.] When the legislature enact, thinking undoubtedly that they were not unjustly enacting, that a bond may be assigned, and that the assignee may thereupon prosecute an action in his own name, and consequently recover to his own use so much of the apparent debt as will remain after allowance of just discounts, which discounts are defined in the 6 § of the act in 1748, to be such as, on trial of an issue in an action prosecuted by the obligee, if he had not assigned the bond, the obligor could have proved, in other words, when the legislature give negotiability, or currency, to bonds by assignment subject to discounts which can be proved on a trial, at law, that is, to legal discounts, if a court, fancying, as appeareth in many parts of the text to have been done, this or that to have been intended or not to have been intended or contemplated by the legislature or, if it was so intended, to be unjust, (p' 253) impose upon a statute a meaning, or rather give it an effect, which is congruous with that fancied intention, so as to include what they call equitable discounts, is not judges indulgence of themselves in such a license a 'real inconvenience?' an inconvenience of a truly dangerous kind; because the legislature cannot apply the remedy: for if supreme judges sanctifie apocalypses of legislative intention, from such topics, withoutregarding

Page 20

regarding legislative words, for canonical, what will statutes signifie?

Multiplex intricate litigation, in consequence of the precedent established (p' 253) hath increased, and is hourly increasing in the high court of chancery and the county courts, since fall term 1796. is not that a 'real inconvenience.'?

Every obligee finds the value of his credits diminished in proportion as the risks of assignees are multiplied by the precedent established. is not that a real inconvenience?

A planter (p' 254,) dealing with an english, a scots, or an irish, merchant or his factor, in Richmond, for a Virginia assigned or indorsed promisory note, which cost the planter 400 pounds sterling is allowed, on account of the drawers latent equity, no more than 300, to which his necessities at the time oblige him to submit. the merchant receives the whole 400 from the drawer. some months afterwards the same planter dealing with the same merchant in London, Edinburgh, or Dublin, becomes his creditor for 400 pounds sterling, and consents to be paid rather in english, &c,' negotiable notes on account of their lighter burthen, than money, but is obliged, because the assignee or indorsee in that country, is not chargeable with the drawers equity to allow pound for pound. is not this difference between the citi-zens

Page 21

zens of Virginia, whom one of the judges chooses to distinguish, (p' 254,) by the appellation, planters,' and the british merchants, whom their king calls his people, as if they were the sheep of his pasture, a real inconvenience?

The commentator, instead of saying any thing on the four next periods refers to the reporters argument for complete satisfaction.

The assignee of a note given by an infant, feme covert, or for a gaming or usurious consideration, does not take it discharged of those objections, but the contrary.' &c.'] Can any thing be less pertinent than this? in these cases, an infant, a feme covert, drawer, in an action upon a promissory note endorsed, or upon a foreign bill of exchange endorsed, or upon an action upon a bond assigned, may plead or on trial prove non esse facta, because in two of the cases by common law, in the others by statutory law, the acts are void, nullities, and therefore not transferable. so that the assignee 'takes' the bond charged, not with an equitable but with a legal 'objection.'

For what reason then shall an equity, originally incorporated with the bond, and which should destroy its obligation, be discharged in the hands of an assignee?] In several places the assignors, that is, obligors, equity, was said to be attached to the 'bond.' this cannot be understood inthe

Page 22

the proper sense. substances attached must be in contact, and therefore tangible. such a substance is the table, of parchment or paper on which are written words signifying acknowledgement of a debt and obligation to pay it, but with which obligors equity, a moral entity, not an object of sense, can not be in contact, unless on the same table be delineated the equity. then indeed assignees right, and obligors equity, appearing on the same superficies, may be said in the proper as well as figurative sense to be attached.

Here the obligors equity is said to be 'incorporated with the bond,' which differs not from the former phrase, otherwise than that 'incorporated denotes a more intimate union than 'attached.'

Now are the equity and the bond incorporated? in other words, are a legal right, demonstrated by a writing, to money, and an equitable right, which is latent, to reparation of detriment, 'occasioned by a sellers defect of title, incorporated, so that they were inseparably concomitant, and was the assignee, taking the right to the money due by the bond, ipso facto, burthened with the obligation of the seller to make the reparation?

1, The assignee was not originally burthened, because that an equitable demand existed was not ostensible by the bond; that any such latent demand existed he had not otherwise informa-

Page 23

tion or cause of suspicion; and the law, which sent the obligee to market with his bond, cautioned those with whom he should deal for it, against no discounts other than such as, in case of a suit, the obligor could prove on trial of an issue at common law, not against equitable demands of any kind. but, according to the 'established precedent' (p' 253) of the court of appeals, 'whose words, (p' 254,) are, 'an assignee of a bond or obligation takes the same subject to ALL the equity of the obligor,' even such demands as arose from transactions to which the bond had no relation, demands on account of negotiations, dealings or engagements aleatory, foeneratory, nautic, emporetic, &c.' in which Love and Donelson have been concerned, may be clamed as equitable discounts against the assignee of bonds for payment of the price of those lands, to which Donelson had a title, for some such there. are can such equity be said to be incorporated with those bonds?

2, The supposition, that the obligors equity incorporated, with the bond, in whatever senses the materials of which this incorporation is compounded, may be understood, will appear a glaring hallucination.

By the term equity, as it is here used, is understood a right to some thing, which right an injured party, because for recovering it the court of law can apply no remedy, must assert before another tribunal, the court of equity.With

Page 24

With this right incorporation, or rather concorporation of the parchment or paper, on which, are written acknowledgement of a debt, and a covenant to pay it, to one or his assigns, was surely not intended. the component parts can no more cohere than the materials of which the feet and toes of Nebuchadnezzars image (Daniel, ch' II, v' 33, 42,) were compounded; and therefore cannot accompany one another into the hands of the assignee.

By 'bond' was perhaps meaned the obligors duty to pay money confessed by that writing to be due, which is the true meaning. if it be so, one mans, e' g,' Loves equitable right to reparation of a detriment occasioned by a deceitful sale, may abrogate the sellers, Donelsons, legal right to the price intirely or partialy whilst the obligee retains the bond. but their action and reaction, in physiologic language, even then would not be simultaneous, as they must be, if they were concorporate, were parts of the same system, or were members, to continue the metaphor, of the same body. Loves equity would not, in the trial at law, resist, as, if the equity and bond were concorporate, it would resist, Donelsons right, if instead of assigning the bond, he had prosecuted an action in his own name. if the equity and bond were not, whilst the latter remained in Donelsons hands, concorporate they could not have been concomitant in Hodgsons hands. Love could nothave

Page 25

have been relieved against either obligee or assignee elsewhere than in the court of equity. there his equitable title would have defeated Donelsons legal title, but,

3, Must there Succumb under the more powerful right of Hodgson, who with his own equitable title had united Donelsons legal title.

The provision of this act has long governed the assignment of bonds, and it is but of late years that the existence of such a principle, as has been contended for in this cause, has been thought of.] The principle, only principle, contended for in that cause was, 'where equity is equal, he who has gained a legal advantage shall prevale,' Washingtons reports, 2 vol' 243; and the same principle

As applicable to bonds and notes.] Was applied to the case of a bond in 1789 by the high court of chancery, and is believed, before 1796, not to have been denied by the court of appeals to be applicable to the case of a bond or of a promissory note.

Carrington j' To consider this case upon general principles; &c'] Of this judges argument only two or three periods will he selected. for praetermission of the rest no reader will ask the commentators reason.

That a bond fraudulent and void in its crea-tion

Page 26

tion cannot be cleansed of its impurity, and rendered valid by assignment is settled by the case of Turton and Benson,[14] and has uniformly been so decided in the courts of this country.]. That the bond if it were proved to have been void in its creation, as in case of an obligation by one in duress, by an infant, by a married woman, or by an insane, or an obligation to perform some malum in se, or malum prohibitum, could not be rendered valid by assignment, would not have been denied, if it had not been 'settled by the case of Turton and Benson, and uniformly so decided in the courts of this country.' that proof, hath not been exhibited; so that the argument, if argument were intended, in this part of the text, wants its complement.

No man can, by the mere act of assignment transfer a greater interest than he holds, dispose of an interest, where he has nothing, or make good and valid that which was originally vicious and void.] This almost self evident proposition, which, lest it should not be noticed, is translated into terms equivalent, would have been pertinent, if the assignee had no right besides what he derived from the obligee, whereas the assignee hath a right which the statute gives to him, besides the right of the obligee: the proposition is therefore not pertinent.

By such as this, (what shall it be be called?surely

Page 27

surely not) reasoning, this judge no doubt expected that his auditors and readers would be no less 'CLEAR' than he was (p' 253,) that the chancellors decree in the case of Norton against Rose was 'erroneous'—auditors and readers too

'In this enlightened age.']

Lyons j.' This has been truly said to be a case of considerable importance on account of the precedent to be established.'] The cause truly was important on account of the precedent, and on account of opinions which established the precedent.

In order to discover the legislative intention, when the act of 1730 (of which that of 1748 is an exact copy as to this question) was passed and to comprehend more clearly the consequences of the construction contended for by the appellee, i shall consider this case as if it had been to be decided upon at that time.] He, who might from this prooemium expect to be enabled, to 'discover what he could not have discovered or to comprehend what he could not have comprehended,' if the reporter had not obliged the world by publishing this judges lucubrations, Will probably be disappointed.

If Norton had given this bond before assignments were sanctioned by legislative authority, it is admitted on all hands, that his equity wouldhave

Page 28

have followed the bond into the hands of an assignee.] If that, before assignments were sanctioned by legislative authority, the obligors equity followed the bond into the assignees hands, be admitted, is a conclusion, that after assignments were sanctioned by legislative authority the obligors equity followed the bond into the assignees hands, more cogent logic than what preceded?

If so, is it possible that the legislature could have meditated so much injustice as to exclude him from setting up an objection to the debt which, but for the law, he might have made?'] The commentator will not answer this question directly, thinking it will appear preposterous, as it is unnecessary, to him who shall considerately answer two other questions subjoined to the case now stated.

Donelson, who sold lands, part of which was the property of others, to Love, covenanted to warrant the title.

For payment of the purchase money, Love subscribed and to Donelson delivered a paper on which are these written or printed words:

'I John Love, oblige myself to pay 20000 dollars, for which i acknowledge myself a debitor, to Stockley Donelson, or to pay them to any man else producing this obligation to him assigned, and returning it to me.'Donelson,

Page 29

Donelson, trucking or trading at market, transfered the obligation to Hodgson, who, from the words on it could not know, and from other information, doth not appear to have known, for what, whether lands or goods bought, money lent, money won at gaming, &c.' Love acknowledged himself to be debitor.

The legislature, long before this transaction had instituted a law, by which Hodgson was authorized to prosecute an action in his own name for recovering the debt, allowing what discounts Love could prove, on trial of an issue at law, against both Donelson and Hodgson, to which law Love was no stranger.

Accordingly Hodgson prosecuted in his own name an action against Love who to it could not plead, because he could not have been on trial allowed, a discount for the equity now clamed by him.

Question 1, ought the loss, which may be occasioned by Donelsons inability to convey a title, and his insolvency, to be borne by Love or Hodgson;—by him, who was not only confessed by himself to be a debitor, and who in explicite terms obliged himself to pay money to the obligees creditor the assignee, but was a concealer of an objection which he had or might have against the paiment, and was warn-ed

Page 30

ed by the law that upon the bond if it should be transfered, against him the assignee might maintain an action; or ought the loss to be borne by him, who was a fair creditor, unapprised of the obligors equity, and informed by the statute, that he must allow discounts, discounts only, which the obligor could prove at the trial, the trial of an issue at common law; not any equitable demands against the obligor which might be justified at the hearing of a cause, or more causes than one, in chancery, causes which had no connexion with the contract whence the bond originated?

Some people think that of injustice the legislature could not have been convicted, if it had in so many terms, as it hath in equivalent terms enacted, that the assignee should allow discounts only which could regularly be proved on trial of an issue at common law.

Question 2, When the words of the statute had given a legal right to the assignee, who hath an equitable right besides, how can judges, presuming an unavoidable inference, from a principle admitted in l' 23 of p' 254, by one, and not denied by any other, of the triad, to be unjust, venture to impose upon the statute a meaning opposite to that inferrence? a judge, disposed to take such liberty, will find the transition from nomophylax* a preserver of thelaws

* This term is used here, not in its peculiar sense when it designated a certain athenian magistrate so called but, in a more general sense, which its etymon will justifie,

Page 31

laws to nomothetes, a maker of laws, not difficult.

Could it mean to protect fraud,'] This question aptly followeth its leaders. in like manner to shew how little pertinent it is, the commentator, instead of answering it, will ask a question.

Doth the legislature, saying that an assignee, per hypothesin a fair purchaser, of a bond, shall allow discounts which can be proved upon trial of an issue, protect fraud, or do the court of appeals, by their precedent, telling the obligor that he may conceal from the assignee demands against the obligee which might have been published with the bond by insertion of half a dozen words in it, protect fraud? and what frauds contrived between obligor and assignor, may not this precedent protect?

And to give validity to an instrument which was originally void, and founded in deception?] The bonds inanity hath been denied before.

Whatever would then have been the construction of the law must be the construction of it at this day. &c.'] This period and what followeth it to the end pf the paragraph, the commentator would have analysed, but he cannot discover any thing in it, except what hath been noticed, like reasoning.'The

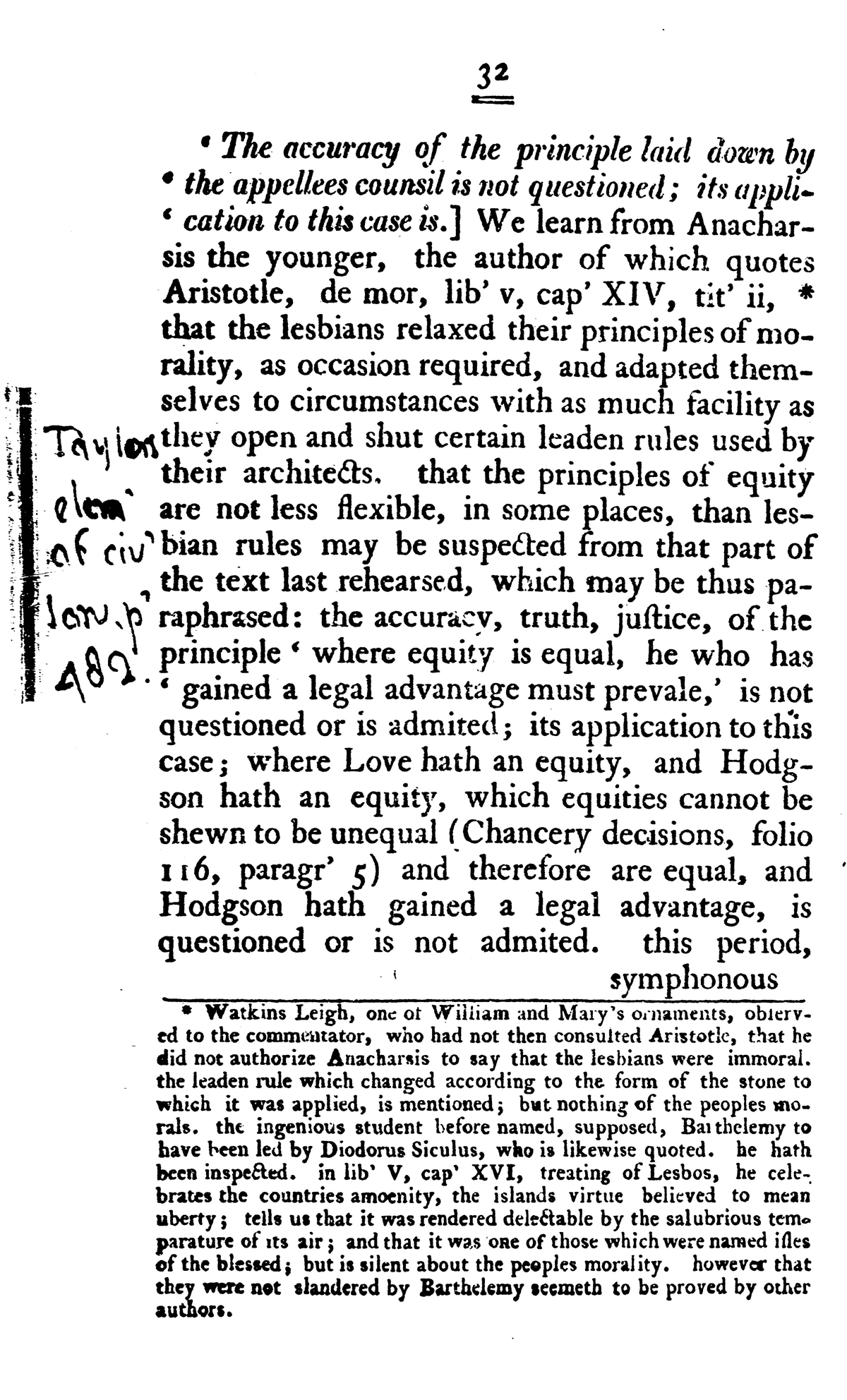

Page 32

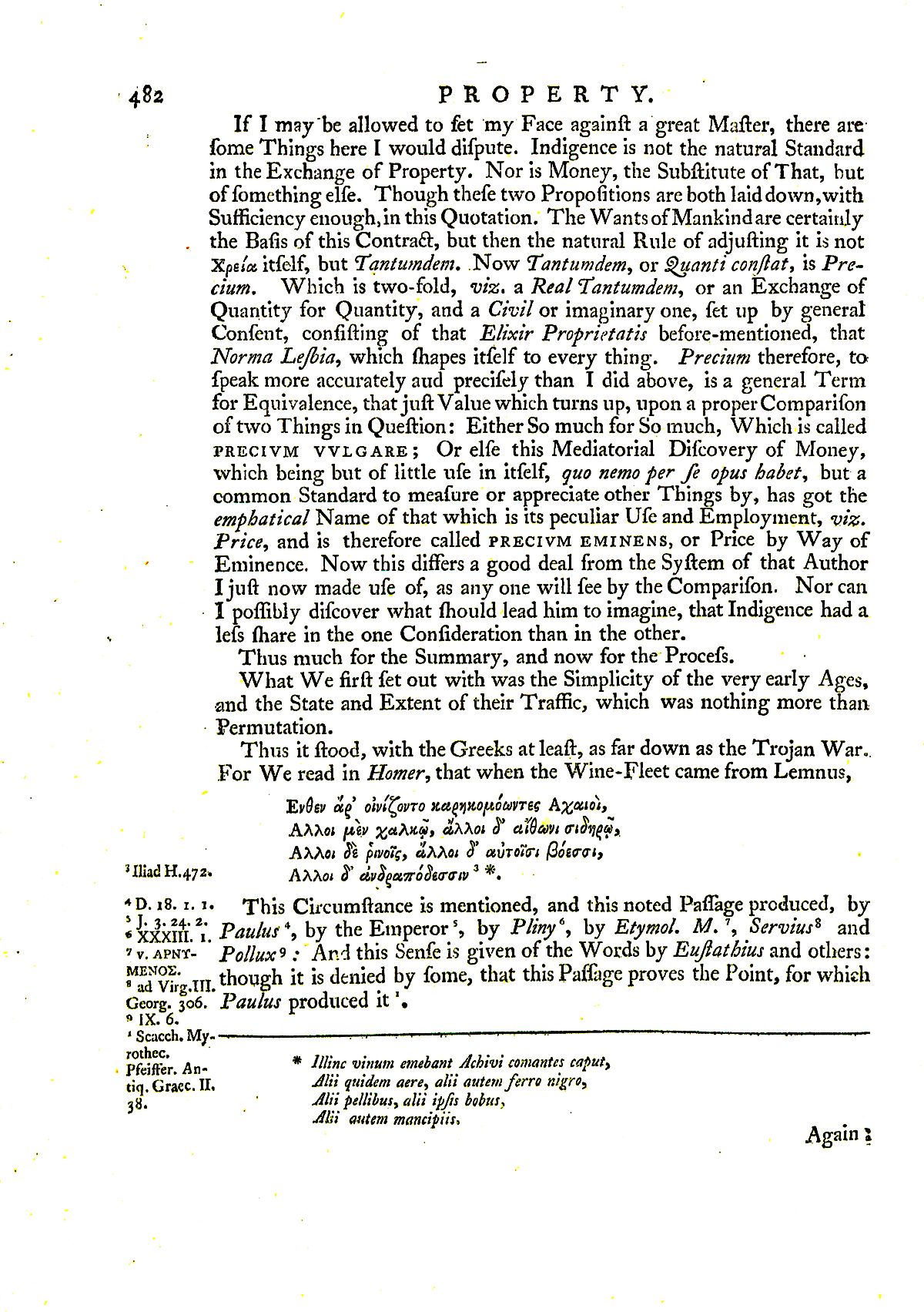

'The accuracy of the principle laid down by the appellees counsil is not questioned; its application to this case is.] We learned from Anacharsis the younger, the author of which quotes Aristotle, de mor, lib' v, cap' XIV, tit' ii,* that the lesbians relaxed their principles of morality, as occasion required, and adapted themselves to circumstances with as much facility as they open and shut certain leaden rules used by their architects. that the principles of equity are not less flexible, in some places, than lesbian rules may be suspected from that part of the text last rehearsed, which may be thus paraphrased: the accuracy, truth, justice, of the principle 'where equity is equal, he who has gained a legal advantage must prevale,' is not questioned or is admitted; its application to this case; where Love hath an equity, and Hodgson hath an equity, which equities cannot be shewn to be unequal (Chancery decisions, folio 116, paragr' 5)[15] and therefore are equal, and Hodgson hath gained a legal advantage, is questioned or is not admited. this period,symphonous

* Watkins Leigh, one of William and Mary's ornaments, observed to the commentator, who had not then consulted Aristotle, that he did not authorize Anacharsis to say that the lesbians were immoral. the leaden rule which changed according to the form of the stone to which it was applied, is mentioned; but nothing of the peoples morals.[16] the ingenious student before named, supposed, Barthelemy to have been led by Diodorus Siculus, who is likewise quoted. he hath been inspected. in lib' V, cap' XVI, treating of Lesbos, he celebrates the countries amoenity, the islands virtue believed to mean uberty; tells us that it was rendered delectable by the salubrious temperature of its air; and that it was one of those which were named isles of the blessed; but is silent about the peoples morality. however that they were not slandered by Barthelemy seemeth to be proved by other authors.

Page 33

symphonous with much of the argumentation which it closeth; shall be taken for epilogue. and with it here endeth the commentary.

The judge of the high court of chancery fully convinced that the reversing decree in the case of Norton against Rose, before establishment of it for a precedent, deserves a reconsideration at least, that the court of appeals, may have opportunity which no doubt the paintiff [sic] appealing will give to enjoy the pleasure which will result from approbation, after severe examination, of one of their precedents, or, if it be not approved, from their palinodie of it, the pleasures which he who is a lover of truth and justice, he who is

—uni aequus virtuti atque ejus amicis,[17]

Postscript. George Washington Campbell, of Tennessee, hath on this case given his opinion, which, with one section of a Northcarolina statute, enacting that bonds, &c.' shall be deemed negotiable and transferable by indorsement in the same manner and under the same regulations and restrictions as promisory or negotiable notes had theretofore been; and that indorsees may in their own names maintain actions for recovering the money due by the bonds, &c' is among the exhibits.

only can relish, doth dismiss the bill with costs.He

Page 34

He mentions the laws of England upon the subject of choses en action, which, so far as they relate to this case, have been considered, and he supposes that 'contracts in general, with respect to their construction or interpretation and effect, &c,' ought to he governed by the laws of that countrie in which they were 'entered into;' upon which nothing need be said here, because any difference, as to the present question, is not discerned between the Virginia statute and the foresaid section of the Northcarolina statute, which last, with him, the judge of the high court of chancery supposeth to he in force in Tennessee: for

Even adventurers in colonic emigrations to territories unoccupied, before they form a politie for themselves, observe and are governed by their metropolitan laws and institutes; unquestionably therefore the people who, retaining their antient possessions, dissever and form a new state for more convenient adminstration of their civic affairs in a narrower sphere, shall observe and be governed by the antient laws, which were common to them and the people of their mother state.

See also

- Between Fowler and Saunders

- Between Wilkins and Taylor

- Between Yates and Salle

- The Case of Overtons Mill: Prolegomena

- Case upon the Statute for Distribution (pamphlet)

- Love v. Donelson

- Report of the Case between Aylett and Aylett

- Report of the Case between Field and Harrison

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Love, against Donelson and Hodgson (Richmond, VA: Thomas Nicolson, 1801?).

- ↑ It is the opinion of the editors that the Chancellor would have understood that the new century began January 1, 1801. A similar reference to 1789 being the "eighty ninth year of the eighteenth centurie" (p. 3 in this report) supports this conclusion.

- ↑ Edwin James Smith, "Benjamin Watkins Leigh," John P. Branch Historical Papers of Randolph-Macon College, no. 4 (June 1904), 287.

- ↑ Charles Evans, in his American Bibliography, vol. 11 (1942), mistakenly gives the date of publication as 1796.

- ↑ Benjamin Blake Minor, ed., Decisions of Cases In Virginia, By the High Court Chancery, with Remarks Upon Decrees By the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, by George Wythe (Richmond, Virginia: J.W. Randolph, 1852), xli.

- ↑ Minor had access to a bound volume of pamphlets which had belonged to James Madison, and was then in the possession of William Green of Culpeper, Virginia. The Catalogue of the Choice and Extensive Law and Miscellaneous Library of the late Hon. William Green, LL.D.,... to be sold by Auction, January 18th, 1881, at Richmond, VA. (Richmond: John E. Laughton, Jr., 1881), lists the volume as follows (p. 200). Mysteriously missing from the catalogue, however, is an entry for Between Yates and Salle, specifically mentioned by Minor to have been issued as a pamphlet, presumably provided by Green (Minor, p. 163).

2325. WYTHE'S REPORTS. Aylett & Aylett, Richmond: 1796; Field & Harrison, Richmond: 1796. WYTHE (GEO.). Case upon the Statute for Distribution, Richmond: 1796. Wilkins & John Taylor, et als.; Fowler & Saunders. In one vol., 12mo. Auto. of President James Madison. Ms. notes. A rare collection of the Original Imprints, supposed by the late possessor to be unique.

- ↑ "Six tracts originally bound together in calf for Jefferson by Milligan on June 30, 1807 (cost $1.00). Rebound in Buckram for the Library of Congress." E. Millicent Sowerby, comp., Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1953), [2:208].

- ↑ Library of Congress catalog record. This volume contains pamphlets for: Case upon the Statute for Distribution (1796); Field v. Harrison (1794); Fowler v. Saunders and Goodall v. Bullock (1798, together in the same pamphlet); Wilkins v. Taylor (1799); Yates v. Salle (1792); and Love v. Donelson (1801). See also: Aylett v. Aylett (1793), and Overton v. Ross (1803).

- ↑ "Manuscript notes by Wythe." Sowerby, 2:209.

- ↑ Calchas was the prophet of Troy. Homer, Iliad 1.69.

- ↑ Norton v. Rose 2 Wash. 233 (Va. 1796).

- ↑ 3 & 4 Anne, cap. 9.

- ↑ William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield. Peacock v. Rhodes 2 Doug. 633.

- ↑ Turton v. Benson, 1 P. Wms. 496.

- ↑ Overstreet v. Randolph, Wythe 49 (1789): "The reason of the opinion, namely, that the assignees equity is not less than the obligors equity, is still believed to be correct. for although where the equity of one party and the equity of another are homogeneous, their quantities may be compared together, and their difference, if they be not equal, may be determined as accurately, perhaps, as quantities, which are the subjects of geometrical calculation: yet the equity of an obligor, injured by the fraud of the obligee, and the equity of an assignee of the obligation, for valuable consideration, without notice, injured by loss of his debt, being so unlike, that they can not be compared together, in order to shew which is the greater, must be supposed equal."

- ↑ "For what is itself indefinite can only be measured by an indefinite standard, like the leaden rule used by Lesbian builders; just as that rule is not rigid but can be bent to the shape of the stone, so a special ordinance is made to fit the circumstances of the case." Nichomachean Ethics, 5:10.

- ↑ "A friend equally to virtue and to virtue's friends." Horace, Satyrarum Libri, 2:1:70.

External links

- Library of Congress catalog record.

- Sowerby Catalogue, at HathiTrust.