Difference between revisions of "Blackstone's Commentaries"

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|set=4 volumes in 5 | |set=4 volumes in 5 | ||

|desc=8vo (22 cm.) | |desc=8vo (22 cm.) | ||

| − | }}[[File:TuckerBlackstonesCommentary1803V2Table.jpg|left|thumb|350px|<center>Table of Descents in Parentage in Virginia, plate IV, volume two.</center>]][[St. George Tucker]] (1752–1827) was a Virginia jurist and former student of George Wythe.<ref>The description of Tucker's ''Blackstone'' derives from the Wikipedia entry for [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._George_Tucker St. George Tucker] that Fred Dingledy (of William & Mary's Wolf Law Library) edited and refined.</ref> When he succeeded Wythe as the second [[Professor of Law and Police]] at the College of William & Mary, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._George_Tucker Tucker] used [[Commentaries on the Laws of England|William Blackstone's ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'']] as his primary text.<ref>Paul Finkelman and David Cobin, "An Introduction to St. George Tucker's Blackstone's Commentaries," in St. George Tucker, ''Blackstone's Commentaries'' (1803; repr., Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 1996), 1:x.</ref> Although Tucker considered ''Blackstone'' the best treatise to use for learning the common law, he thought it had weaknesses as a teaching tool for American law.<ref>Ibid. </ref> None of the editions of ''Blackstone'' published in the United States actually discussed new legal developments there; they just reprinted Blackstone's discussions of English law.<ref>Ibid., 1:i.</ref> Tucker also felt that Blackstone's sympathy with the power of the Crown over that of Parliament would be a poor influence for American students.<ref>Davison M. Douglas, " | + | }}[[File:TuckerBlackstonesCommentary1803V2Table.jpg|left|thumb|350px|<center>Table of Descents in Parentage in Virginia, plate IV, volume two.</center>]][[St. George Tucker]] (1752–1827) was a Virginia jurist and former student of George Wythe.<ref>The description of Tucker's ''Blackstone'' derives from the Wikipedia entry for [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._George_Tucker St. George Tucker] that Fred Dingledy (of William & Mary's Wolf Law Library) edited and refined.</ref> When he succeeded Wythe as the second [[Professor of Law and Police]] at the College of William & Mary, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._George_Tucker Tucker] used [[Commentaries on the Laws of England|William Blackstone's ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'']] as his primary text.<ref>Paul Finkelman and David Cobin, "An Introduction to St. George Tucker's Blackstone's Commentaries," in St. George Tucker, ''Blackstone's Commentaries'' (1803; repr., Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 1996), 1:x.</ref> Although Tucker considered ''Blackstone'' the best treatise to use for learning the common law, he thought it had weaknesses as a teaching tool for American law.<ref>Ibid. </ref> None of the editions of ''Blackstone'' published in the United States actually discussed new legal developments there; they just reprinted Blackstone's discussions of English law.<ref>Ibid., 1:i.</ref> Tucker also felt that Blackstone's sympathy with the power of the Crown over that of Parliament would be a poor influence for American students.<ref>Davison M. Douglas, "[http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol47/iss4/2/ Foreword: The Legacy of St. George Tucker]," 47 ''William and Mary Law Review'' (2006), 1113.</ref> To address these deficiencies, Tucker wrote [[marginalia]] in his copy of ''Blackstone'' and read the notes to his classes. He also added lectures on the law of Virginia and the United States, comparing the American political system with its British counterpart.<ref> Charles T. Cullen, ''St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia, 1772-1804'' (New York: Garland Publishing, 1987), 121,123-126.</ref><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

In 1795, at the urging of several friends (including former Virginia governor John Page), Tucker began investigating publishing his written works, including an edition of ''Blackstone'' with his notes and lectures from William & Mary added as appendixes.<ref>Ibid., 157.</ref> After initial unsuccessful attempts to find a printer, Tucker reached an agreement with the Philadelphia firm of Birch and Small, which paid Tucker $4000 for the book's copyright.<ref>Ibid., 157-160.</ref> Tucker's ''Blackstone'' was organized into five volumes. Each volume would begin with Blackstone's original text, with notes from Tucker added, followed by an appendix containing Tucker's lectures and writings on particular subjects.<ref>Ibid., 161. </ref> Blackstone's text was mostly arranged the same way as in the original version, but Tucker organized the appendixes to show what he felt were the most important developments in American law.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | In 1795, at the urging of several friends (including former Virginia governor John Page), Tucker began investigating publishing his written works, including an edition of ''Blackstone'' with his notes and lectures from William & Mary added as appendixes.<ref>Ibid., 157.</ref> After initial unsuccessful attempts to find a printer, Tucker reached an agreement with the Philadelphia firm of Birch and Small, which paid Tucker $4000 for the book's copyright.<ref>Ibid., 157-160.</ref> Tucker's ''Blackstone'' was organized into five volumes. Each volume would begin with Blackstone's original text, with notes from Tucker added, followed by an appendix containing Tucker's lectures and writings on particular subjects.<ref>Ibid., 161. </ref> Blackstone's text was mostly arranged the same way as in the original version, but Tucker organized the appendixes to show what he felt were the most important developments in American law.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | ||

| − | Tucker's ''Blackstone'' sold well from the beginning,<ref> Cullen, | + | Tucker's ''Blackstone'' sold well from the beginning,<ref> Cullen, ''St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia'', 160-161.</ref> and it quickly became the major treatise on American law in the early 19th century.<ref>Douglas, "Legacy of St. George Tucker," 1114.</ref> Law reporter Daniel Call described it as "necessary to every student and practitioner of law in Virginia".<ref>8 Va. (4 Call) xxviii (1833)</ref> Lawyers arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court would frequently cite to Tucker's ''Blackstone''—more often than any other commentator until 1827, the year after the publication of James Kent's ''Commentaries on American Law''.<ref> Cullen, ''St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia,'' 162-163.</ref> The United States Supreme Court cited Tucker's ''Blackstone'' frequently, referring to it in over forty cases.<ref>Finkelman and Cobin, "An Introduction to St. George Tucker's Blackstone's Commentaries," 1:v-vi.</ref> Modern lawyers, legal scholars, and judges still refer to Tucker's ''Blackstone'' to determine how Americans understood both English and American law in the early days of the republic.<ref>Ibid., 1:i-ii, v-vi.</ref> |

[[File:TuckerBlackstonesCommentary1803V3Inscription.jpg|left|thumb|350px|<center>Inscription and bookseller's embossed stamp, front free endpaper, volume three.</center>]] | [[File:TuckerBlackstonesCommentary1803V3Inscription.jpg|left|thumb|350px|<center>Inscription and bookseller's embossed stamp, front free endpaper, volume three.</center>]] | ||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

| − | Listed in the [[Jefferson Inventory]] of [[Wythe's Library]] as "Tucker’s Blackstone 5.v. 8vo." and given by [[Thomas Jefferson]] to his son-in-law, [[Thomas Mann Randolph]]. Later appears on Randolph's 1832 estate inventory as "Tucker's Blackstone (3 odd vols.)' (3 vols., $3.00 value)." Both [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s. v."[http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe Member: George Wythe]," accessed on November 18, 2013.</ref> on LibraryThing and the [https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433 Brown Bibliography]<ref> Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433</ref> include ''Tucker's Blackstone''. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the first edition. | + | Listed in the [[Jefferson Inventory]] of [[Wythe's Library]] as "Tucker’s Blackstone 5.v. 8vo." and given by [[Thomas Jefferson]] to his son-in-law, [[Thomas Mann Randolph]]. Later appears on Randolph's 1832 estate inventory as "Tucker's Blackstone (3 odd vols.)' (3 vols., $3.00 value)." Both [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s.v. "[http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe Member: George Wythe]," accessed on November 18, 2013.</ref> on LibraryThing and the [https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433 Brown Bibliography]<ref> Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433</ref> include ''Tucker's Blackstone''. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the first edition. |

==Description of The Wolf Law Library's Copy== | ==Description of The Wolf Law Library's Copy== | ||

Revision as of 15:39, 2 May 2014

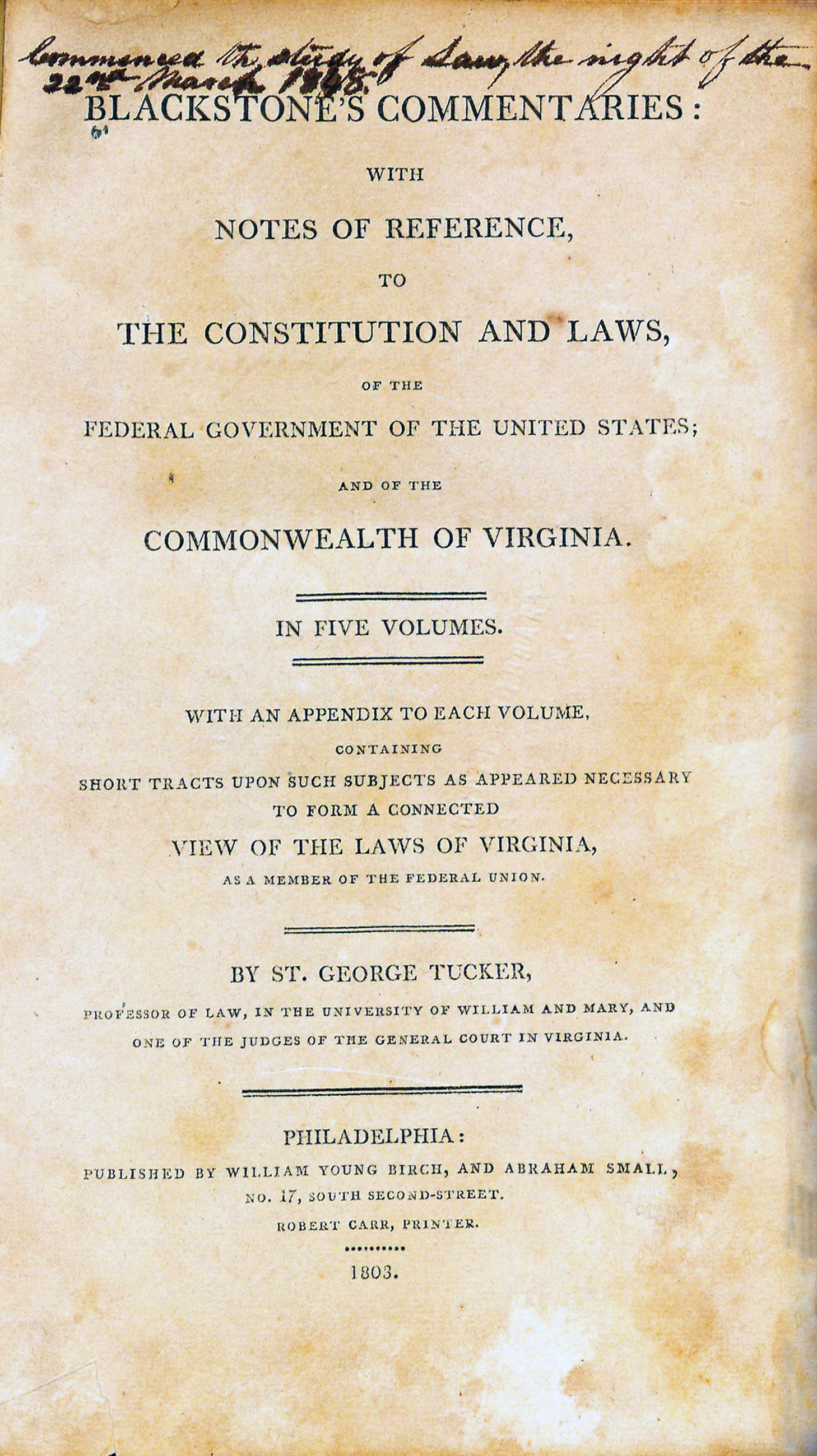

Blackstone's Commentaries: with Notes of Reference, to the Constitution and Laws, of the Federal Government of the United States; and of the Commonwealth of Virginia. In Five Volumes with an Appendix to Each Volume, Containing Short Tracts upon Such Subjects as Appeared Necessary to Form a Connected view of the Laws of Virginia, as a Member of the Federal Union

by St. George Tucker

| Blackstone's Commentaries | |

|

Title page from Blackstone's Commentaries, volume one, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | William Blackstone |

| Published | Philadelphia: Published by William Young Birch, and Abraham Small, no. 17, South Second-street, Robert Carr, printer |

| Date | 1803 |

| Language | English |

| Volumes | 4 volumes in 5 volume set |

| Desc. | 8vo (22 cm.) |

In 1795, at the urging of several friends (including former Virginia governor John Page), Tucker began investigating publishing his written works, including an edition of Blackstone with his notes and lectures from William & Mary added as appendixes.[7] After initial unsuccessful attempts to find a printer, Tucker reached an agreement with the Philadelphia firm of Birch and Small, which paid Tucker $4000 for the book's copyright.[8] Tucker's Blackstone was organized into five volumes. Each volume would begin with Blackstone's original text, with notes from Tucker added, followed by an appendix containing Tucker's lectures and writings on particular subjects.[9] Blackstone's text was mostly arranged the same way as in the original version, but Tucker organized the appendixes to show what he felt were the most important developments in American law.[10]

Tucker's Blackstone sold well from the beginning,[11] and it quickly became the major treatise on American law in the early 19th century.[12] Law reporter Daniel Call described it as "necessary to every student and practitioner of law in Virginia".[13] Lawyers arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court would frequently cite to Tucker's Blackstone—more often than any other commentator until 1827, the year after the publication of James Kent's Commentaries on American Law.[14] The United States Supreme Court cited Tucker's Blackstone frequently, referring to it in over forty cases.[15] Modern lawyers, legal scholars, and judges still refer to Tucker's Blackstone to determine how Americans understood both English and American law in the early days of the republic.[16]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Tucker’s Blackstone 5.v. 8vo." and given by Thomas Jefferson to his son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph. Later appears on Randolph's 1832 estate inventory as "Tucker's Blackstone (3 odd vols.)' (3 vols., $3.00 value)." Both George Wythe's Library[17] on LibraryThing and the Brown Bibliography[18] include Tucker's Blackstone. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the first edition.

Description of The Wolf Law Library's Copy

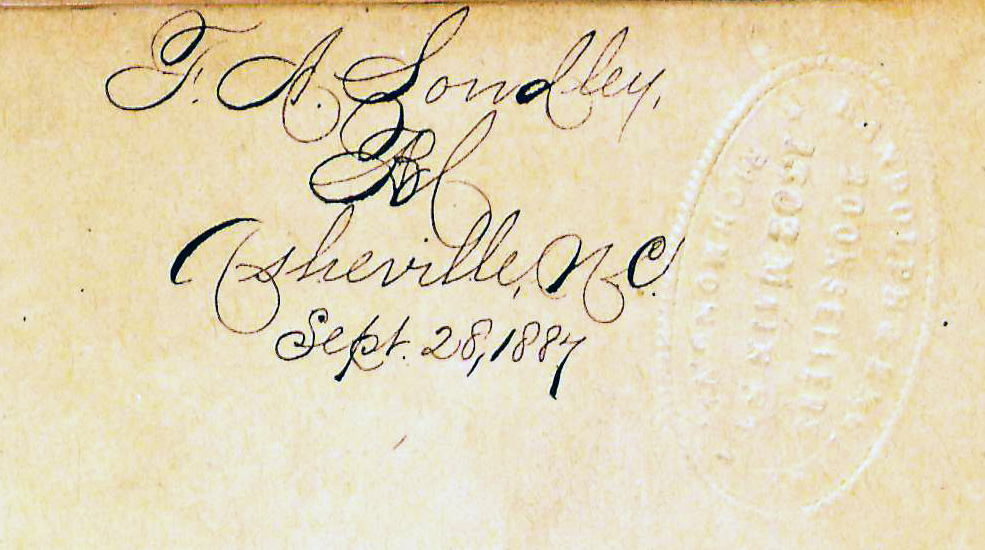

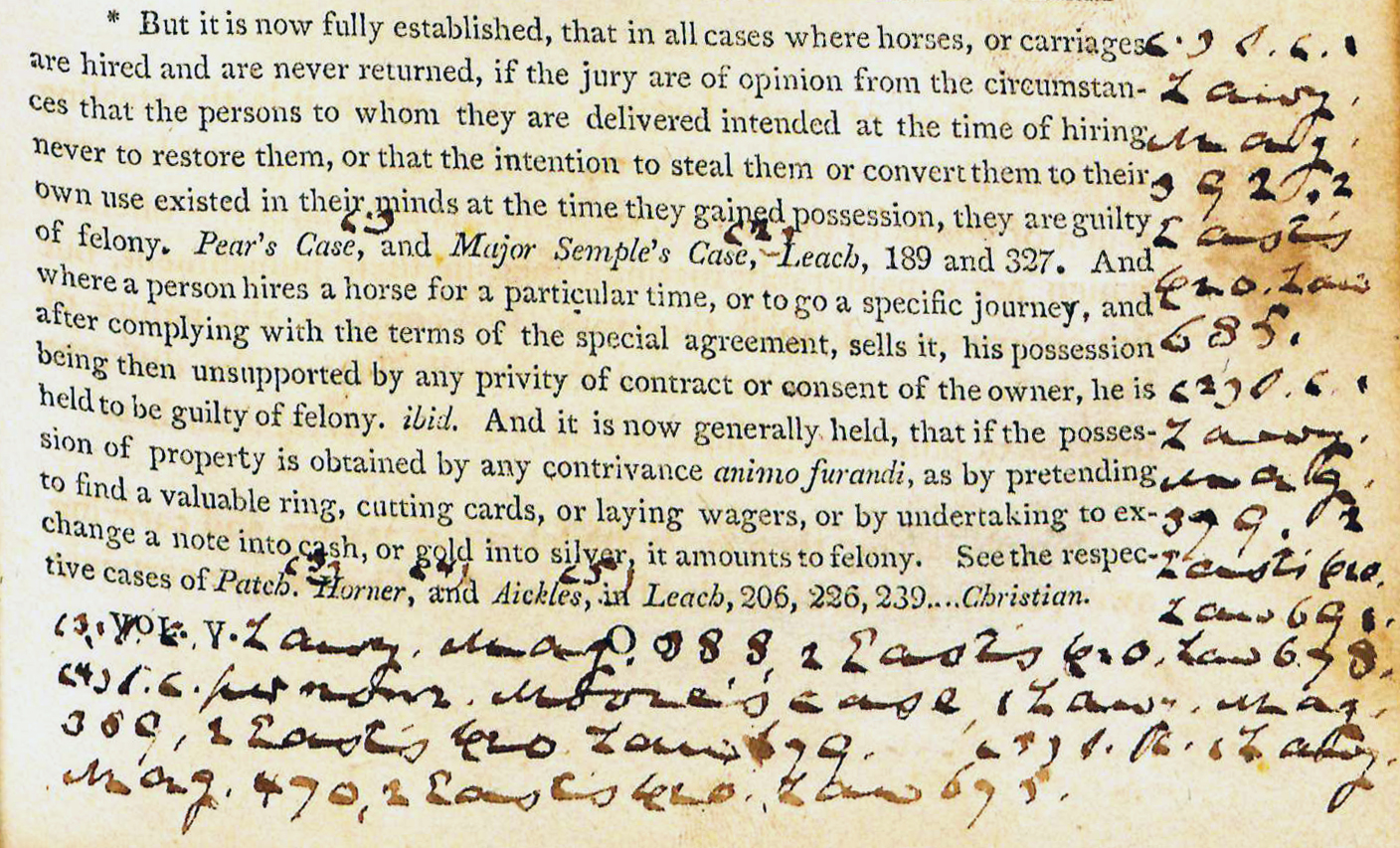

Bound in contemporary calf and rebacked in matching period style, retaining the original red and black morocco gilt-lettered spine labels. Gilt ruling decorates the spine. Contains marginalia throughout the volumes. Each title page embossed with the stamp of the Sondley Reference Library, "Sondley Library, Asheville, NC." Each front free endpaper has the signature of the well-known North Carolina author, lawyer, and historian "F.A. Sondley, Asheville, N.C., Sept. 28, 1887" and the embossed stamp of "Randolph & English, Booksellers, 1502 Main St., Richmond VA." Most volumes signed "Wm. Green, 1834" on a preliminary page; volume three signed "William Green, 1834." Volume three also signed "John W. Green" on the title page. The upper margin of the first volume's title page states, "Commenced the study of Law, the night of the 22nd March 1848." Purchased from David Lesser.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ The description of Tucker's Blackstone derives from the Wikipedia entry for St. George Tucker that Fred Dingledy (of William & Mary's Wolf Law Library) edited and refined.

- ↑ Paul Finkelman and David Cobin, "An Introduction to St. George Tucker's Blackstone's Commentaries," in St. George Tucker, Blackstone's Commentaries (1803; repr., Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 1996), 1:x.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 1:i.

- ↑ Davison M. Douglas, "Foreword: The Legacy of St. George Tucker," 47 William and Mary Law Review (2006), 1113.

- ↑ Charles T. Cullen, St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia, 1772-1804 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1987), 121,123-126.

- ↑ Ibid., 157.

- ↑ Ibid., 157-160.

- ↑ Ibid., 161.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Cullen, St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia, 160-161.

- ↑ Douglas, "Legacy of St. George Tucker," 1114.

- ↑ 8 Va. (4 Call) xxviii (1833)

- ↑ Cullen, St. George Tucker and Law in Virginia, 162-163.

- ↑ Finkelman and Cobin, "An Introduction to St. George Tucker's Blackstone's Commentaries," 1:v-vi.

- ↑ Ibid., 1:i-ii, v-vi.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on November 18, 2013.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

External Links

Read volume four of this book in Google Books.