Difference between revisions of "Wythe Monument"

m |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

After [[Death of George Wythe|George Wythe's death]] in 1806, the Virginia General Assembly voted to wear a "[[National Intelligencer, 15 December 1806|badge of mourning]]" for one month, as a sign of respect to Wythe's contributions to both the Commonwealth, and as a founder of the United States.<ref>''National Intelligencer, and Washington Advertiser'' (Washington, D.C.), 15 December 1806, 2; ''Journals of the Council of Virginia,'' vol. 27, 448. Cited in Imogene E. Brown, ''American Aristides: A Biography of George Wythe'' (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1981), 301.</ref> The executor of [[Last Will and Testament|Wythe's will]], William DuVal, however, would have preferred that the legislature had "erected at the public Expence a plain Tomb Stone, to transmit to future ages the High Lines they entertained of his Talents, his Patriotism, and his inflexible Integrity — his was a rare Character, such an One as is scarcely to be met with in many Centuries."<ref>[[Jefferson-DuVal Correspondence#William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, 10 December 1806|William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, 10 December 1806]], [http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib016653 ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers,''] Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827, Library of Congress.</ref> Later efforts to procure a suitable monument for Wythe were reported in the [[Venerable Old Tree|Richmond ''Times'']] in 1894 and 1901, made by Judge Conway Robinson, and Congressman John Lamb.<ref>W.P.P., "[[Venerable Old Tree|A Venerable Old Tree]]," ''The Times'' (Richmond, VA), October 28, 1894, 9; "[[In Wythe's Memory]]," ''The Times'' (Richmond, VA), January 12, 1901, 4.</ref> | After [[Death of George Wythe|George Wythe's death]] in 1806, the Virginia General Assembly voted to wear a "[[National Intelligencer, 15 December 1806|badge of mourning]]" for one month, as a sign of respect to Wythe's contributions to both the Commonwealth, and as a founder of the United States.<ref>''National Intelligencer, and Washington Advertiser'' (Washington, D.C.), 15 December 1806, 2; ''Journals of the Council of Virginia,'' vol. 27, 448. Cited in Imogene E. Brown, ''American Aristides: A Biography of George Wythe'' (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1981), 301.</ref> The executor of [[Last Will and Testament|Wythe's will]], William DuVal, however, would have preferred that the legislature had "erected at the public Expence a plain Tomb Stone, to transmit to future ages the High Lines they entertained of his Talents, his Patriotism, and his inflexible Integrity — his was a rare Character, such an One as is scarcely to be met with in many Centuries."<ref>[[Jefferson-DuVal Correspondence#William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, 10 December 1806|William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, 10 December 1806]], [http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib016653 ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers,''] Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827, Library of Congress.</ref> Later efforts to procure a suitable monument for Wythe were reported in the [[Venerable Old Tree|Richmond ''Times'']] in 1894 and 1901, made by Judge Conway Robinson, and Congressman John Lamb.<ref>W.P.P., "[[Venerable Old Tree|A Venerable Old Tree]]," ''The Times'' (Richmond, VA), October 28, 1894, 9; "[[In Wythe's Memory]]," ''The Times'' (Richmond, VA), January 12, 1901, 4.</ref> | ||

| − | Following his state funeral in Richmond, Virginia, Wythe had been buried at the historic [http://historicstjohnschurch.org/ St. John's Church] without a headstone, and the exact location of his grave has been forgotten: as early as 1884, Wythe's namesake [[Chancellor Wythe's Death|George Wythe Munford wrote]], "There is no monument or other mark to designate the spot where his remains repose; but it is believed he was buried on the west side of the church, near the wall of that building."<ref>George Wythe Munford, [[Two Parsons|''The Two Parsons; Cupid's Sports; The Dream; and The Jewels of Virginia'']] (Richmond, Virginia: J.D.K. Sleight, 1884), 429.</ref><ref>An article in the Baltimore ''Sun'' on September 25, 1904, however, records that the grave was "shaded by an elm tree and identified by a piece of iron driven in at the head." Reprinted in Louise Pecquet du Bellet, [https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_tyQSAAAAYAAJ/page/n35 ''Some Prominent Virginia Families''] (Lynchburg, VA: J.P. Bell, 1907)2: 24.</ref> Indeed, at the time of his death in 1806, the [[Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806|Richmond ''Enquirer'']] commented that "the venerable George Wythe needs no other monument than the services rendered to his country, and the universal sorrow which that country sheds over his grave."<ref>[[Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806|''The Enquirer'' (Richmond, VA), June 10, 1806, 3.]]</ref> | + | Following his state funeral in Richmond, Virginia, Wythe had been buried at the historic [http://historicstjohnschurch.org/ St. John's Church] without a headstone, and the exact location of his grave has been forgotten: as early as 1884, Wythe's namesake [[Chancellor Wythe's Death|George Wythe Munford wrote]], "There is no monument or other mark to designate the spot where his remains repose; but it is believed he was buried on the west side of the church, near the wall of that building."<ref>George Wythe Munford, [[Two Parsons|''The Two Parsons; Cupid's Sports; The Dream; and The Jewels of Virginia'']] (Richmond, Virginia: J.D.K. Sleight, 1884), 429.</ref><ref>An article in the Baltimore ''Sun'' on September 25, 1904, however, records that the grave was "shaded by an elm tree and identified by a piece of iron driven in at the head." Reprinted in Louise Pecquet du Bellet, [https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_tyQSAAAAYAAJ/page/n35 ''Some Prominent Virginia Families''] (Lynchburg, VA: J.P. Bell, 1907) 2:24.</ref> Indeed, at the time of his death in 1806, the [[Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806|Richmond ''Enquirer'']] commented that "the venerable George Wythe needs no other monument than the services rendered to his country, and the universal sorrow which that country sheds over his grave."<ref>[[Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806|''The Enquirer'' (Richmond, VA), June 10, 1806, 3.]]</ref> |

An unmarked grave was not unusual at that time, even for such luminaries as signers of the [[Declaration of Independence]]. In October of 1899, Mary Mann Page Newton, chairman of the Landmark Committee for the Virginia Association for the Preservation of Antiquities, reported: | An unmarked grave was not unusual at that time, even for such luminaries as signers of the [[Declaration of Independence]]. In October of 1899, Mary Mann Page Newton, chairman of the Landmark Committee for the Virginia Association for the Preservation of Antiquities, reported: | ||

Latest revision as of 15:12, 21 May 2021

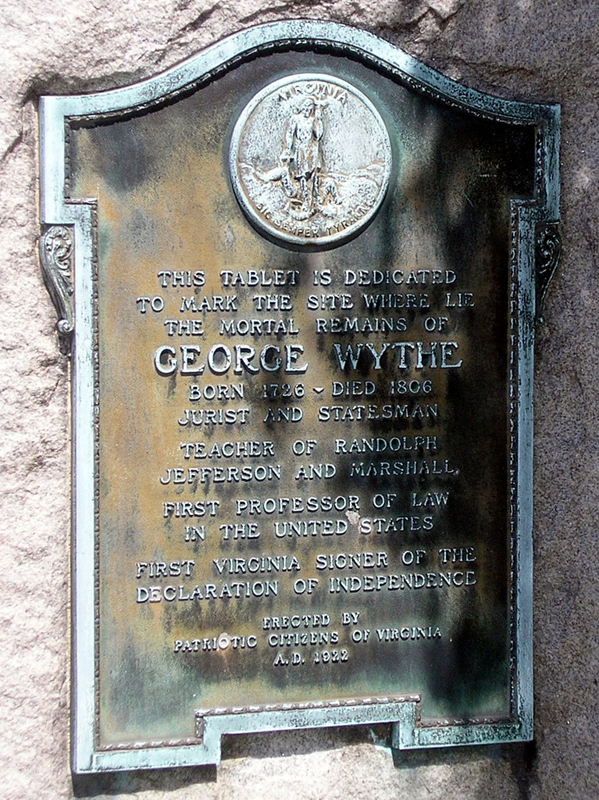

Monument to mark George Wythe's burial at St. John's Episcopal Church, East Broad Street, Richmond, Virginia.

A smaller plaque at the base of the column was placed sometime after 2004 by Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, Inc., to commemorate Wythe as a signer.

After George Wythe's death in 1806, the Virginia General Assembly voted to wear a "badge of mourning" for one month, as a sign of respect to Wythe's contributions to both the Commonwealth, and as a founder of the United States.[1] The executor of Wythe's will, William DuVal, however, would have preferred that the legislature had "erected at the public Expence a plain Tomb Stone, to transmit to future ages the High Lines they entertained of his Talents, his Patriotism, and his inflexible Integrity — his was a rare Character, such an One as is scarcely to be met with in many Centuries."[2] Later efforts to procure a suitable monument for Wythe were reported in the Richmond Times in 1894 and 1901, made by Judge Conway Robinson, and Congressman John Lamb.[3]

Following his state funeral in Richmond, Virginia, Wythe had been buried at the historic St. John's Church without a headstone, and the exact location of his grave has been forgotten: as early as 1884, Wythe's namesake George Wythe Munford wrote, "There is no monument or other mark to designate the spot where his remains repose; but it is believed he was buried on the west side of the church, near the wall of that building."[4][5] Indeed, at the time of his death in 1806, the Richmond Enquirer commented that "the venerable George Wythe needs no other monument than the services rendered to his country, and the universal sorrow which that country sheds over his grave."[6]

An unmarked grave was not unusual at that time, even for such luminaries as signers of the Declaration of Independence. In October of 1899, Mary Mann Page Newton, chairman of the Landmark Committee for the Virginia Association for the Preservation of Antiquities, reported:

Another important work to be done at St. John's is to place some monument on the unmarked grave of Chancellor George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and one of our greatest jurists and purest statesmen. The site of Judge Wythe's home, at the southeast corner of Grace and Fifth streets, now occupied by the residence of Mr. Beverley B. Munford, should also be marked...[.]

Though the glory of the signers of the Declaration of Independence is also Revolutionary, it would doubtless come with perfect propriety within the scope of our own work to mark the places where they sleep. As I have said, George Wythe's grave in St. John's churchyard, has no monument, and it is believed that this is also the case with the last earthly resting-places of Benjamin Harrison, Richard Henry and Francis Lightfoot Lee, and Carter Braxton. [7]

In 1920, the Virginia Bar Association partnered with the Sons of the Revolution in State of Virginia, the Virginia Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, and the Virginia Daughters of the American Revolution to begin the process of obtaining and placing a "suitable marker" near the presumed location of Wythe's grave. The final monument was dedicated on May 24, 1922.

Contents

- 1 Annual Reports of the Virginia State Bar Association, 1920

- 2 Annual Reports of the Virginia State Bar Association, 1921

- 3 Sons of the Revolution in Virginia, April 1922

- 4 Annual Reports of the Virginia State Bar Association, 1922

- 5 Proceedings of the Virginia State Conference of the Daughters of the American Revolution, October 1922

- 6 See also

- 7 References

Annual Reports of the Virginia State Bar Association, 1920

At the 1920 meeting of the Virginia State Bar Association, John B. Minor, Secretary-Treasurer, read a letter from Arthur B. Clarke, President of the Virginia Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, concerning a local effort to erect a suitable monument for Wythe's grave:[8]

Secretary Minor: Mr. President, I have two communications, one of which is a communication from the Virginia Society of the Sons of the American Revolution in, relation to some marker for the grave of George Wythe, which I will read:

616 AMERICAN N. B. BLDG., RICHMOND, VA.,

May 7, 1920.HON. JOHN B. MINOR, Prest. Bar Association,

- 506 Mutual Building, Richmond, Va.

My dear Mr. Minor:

Wide attention has been called to the neglected graves, in several states, of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, and a movement is being made to have all such graves marked by stones.

One such, grave is in this city.

Chancellor George Wythe, one of the Signers, one of the most distinguished lawyers of Virginia, a great expounder and great teacher of the law, is buried in old St. John's graveyard on Church Hill, just at the door of the old church. No stone marks the resting place of this man to whom this state owes so much.

Comment on his life and deeds needs not be made in this letter. His accomplishments are known to all members of the Bar Association or should be.

The patriotic societies of this city have appointed committees to take up the matter of marking this grave, and I am sure your Association need only to have its attention called to the matter to approve of the movement, and likewise appoint a committee to co-operate with representatives of other organizations.

Trusting you will bring the subject to the attention of your Association, with desired results, I am

- Yours very truly,

- ARTHUR B. CLARKE,

- Prest. Va. So. S. A. R.

I move that this communication be referred to the Committee on Resolutions, with instructions to report a suitable resolution in accordance with the request.

Seconded and adopted.

The next day, the Bar Association's Committee on Resolutions produced the following:[9]

Be it Resolved, That the Virginia State Bar Association heartily approves the movement inaugurated by the patriotic organizations of the city of Richmond to mark the grave of Chancellor George Wythe, and directs the President of the Association to appoint a committee to co-operate in the accomplishment of this purpose with the committees of other organizations.

Annual Reports of the Virginia State Bar Association, 1921

The proceedings of the 1921 meeting of the Virginia Bar Association includes the names of the members appointed to the "Special Committee to Aid in Securing Suitable Marker for Grave of George Wythe": Robert M. Hughes, of Norfolk; Eppa Hunton, Jr., of Richmond; and Eugene C. Massie of Richmond.[10] Hughes had previously served as a member of the committee that placed a memorial tablet dedicated to Wythe in the chapel of the Wren Building at the College of William & Mary, in 1893.

Sons of the Revolution in Virginia, April 1922

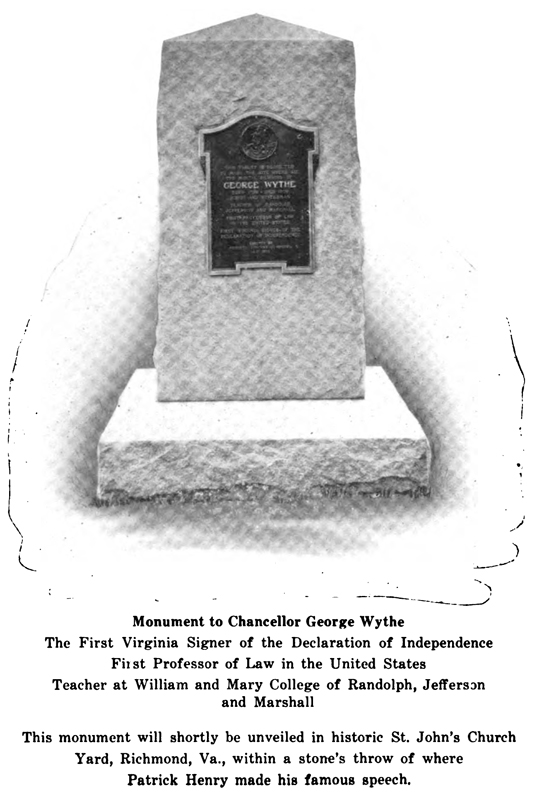

In 1922, in the April issue of Sons of the Revolution in State of Virginia Quarterly Magazine, there appeared a photograph of the as-yet-unveiled "Monument to Chancellor George Wythe,"[11] captioned:

The First Virginia Signer of the Declaration of Independence

First Professor of Law in the United States

Teacher at William and Mary College of Randolph, Jefferson

and Marshall

This monument will shortly be unveiled in historic St. John's Church

Yard, Richmond, Va., within a stone's throw of where

Patrick Henry made his famous speech.

Annual Reports of the Virginia State Bar Association, 1922

Following the unveiling of the monument to Wythe on May 24, 1922, two reports concerning the event were presented to the Virginia State Bar Association, as well as the text of the memorial address delivered by George Bryan:[12]

Page 40

REPORT OF COMMITTEE ON LIBRARY AND LEGAL

LITERATURE.To the Virginia State Bar Association:

Your Committee on Library and Legal Education would respectfully report that up to this time the Library of the State Bar Association is mainly in gremeo legis; depending in large measure upon the law libraries of the State; and that the legal education referred to in the title is too often meagre and jejune, but that with the record of past teachers in the profession whose names are as lights in the darkness, and whose works do follow them, there is set before the profession such a standard of exalted. excellence as should make every member of our Association proud of that record and jealous for the reputation of our profession.

The names of Wythe, Tucker, Brockenbrough and Minor stand forth pre-eminent in the annals of legal education. From these great teachers, as the fountains, have flowed those streams of learning and wisdom which have enriched and fructified the labors of many who never drank at the source, but who have known the sweet influence of those mighty springs as they flowed into the channels and irrigated the barren fields of strife and contention.

Within a month past in the church-yard of St. John's, Richmond, there has been put up a notable monument to Chancellor Wythe. Upon the bronze tablet set into the granite is the statement of his name, birth, life's work and death; that he was the first professor of law in the United States-the teacher of Randolph, Jefferson and Marshall.

This monument has been erected by members of patriotic societies and of the Bar Association, and by individual admirers of the great teacher, law-giver and law-maker; for let it be remembered that it was he who was the first of the Virginia signers of the Declaration of Independence. In a paper read before the Marshall-Wythe Assembly of William and Mary College, the Chairman of your Committee wrote:

Page 41

"We can well imagine how that distinguished group of Virginians respected the character of George Wythe. An examination of their signature shows that, on the immortal Declaration, his name stands first among them as already mentioned; above that of Thomas Jefferson, the author of the paper, himself; above that of Richard Henry Lee, the "Cicero of the Revolution"; above that of Thomas Nelson, Jr., who had brought from Virginia the resolutions of the Virginia Convention directing Virginia's representatives in Congress to declare for independence. I love to think that the Virginia delegation stood back to yield precedent to the great man whom they and the people of Virginia so greatly loved and revered."

If we lack law libraries, we have had great law teachers to supply that lack.

- Respectfully submitted,

- ROSEWELL PAGE,

- Chairman

June 6, 1922.

REPORT OF SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON MEMORIAL

TO GEORGE WYTHE.To the Virginia State Bar Association:

It is a pleasure to report that on May 24, 1922, a suitable monument was unveiled at the grave of Chancellor George Wythe in the church-yard of St. John's Episcopal Church, on Church Hill, in the City of Richmond. The monument is of granite with a bronze tablet and memorial inscription surmounted by the Great Seal of the Commonwealth of Virginia. This Great Seal was adopted by the Convention of 1776, having been devised by a committee consisting of Richard Henry Lee, George Mason, George Wythe, Robert C. Nicholas, John Page and Arthur Lee. Some have ascribed its classic form to George Mason, who reported it to the Convention; but in Girardin's continuation of Burk's "History of Virginia," it

Page 42

is stated that Wythe was the originator. Dr. Lyon G. Tyler, an authority in Virginia history, thinks Girardin's account is correct, and says: "As Girardin wrote under the supervision of Jefferson, who was keenly alive to all such matters, there can be no reason to doubt the truth of his statement." The records show—and there is no dispute about the fact—that George Wythe and John Page were appointed to superintend engraving of the Seal; and this was finally accomplished under their direction, by an artist in Paris, after unavailing efforts had been made to have the work properly done in America. To sustain his opinion that the Great Seal was originated by George Wythe, Dr. Tyler says:

"Moreover, Wythe was one of the two entrusted with the execution of the seal, and must have penned the words describing it, which have been admired for their clearness and precision: 'Virtue, the genius of the Commonwealth, dressed like an Amazon, resting on a spear with one hand, and holding a sword in the other, and treading on Tyranny, represented by a man prostrate, a crown fallen from his head, a broken chain in his left hand, and a scourge in his right. In the exergue the word VIRGINIA over the head of Virtue, and underneath, the words Sic Semper Tyrannis. On the reverse a group: LIBERTAS, with her wand and pileus; on one side of her, CERES, with the cornucopia in one hand and an ear of wheat in the other; on the other side, AETERNITAS, with the globe and phoenix.'"

In commenting upon this classic conception, Dr. Tyler says:

"Severe in his republicanism, Wythe, like other Virginians of the Revolution, had a scorn for 'the aristocrat,' and found his ideals in the Roman and Grecian Republics. Caesar, Brutus and Cicero were his names to conjure with, and his faith in the ability of man for self-government was stamped upon all his official action. While Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hamp-

Page 43

shire, along with New York Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Maryland, and even the United States, clung to the old ideas of English heraldry and fashioned their seals of State on the principle of a coat of arms, Virginia, under the direction of Wythe, chose a purely classic design. She alone of the thirteen original States has no shield on which to emblazon in dazzling colors and lustrous metal the memory of feudal services, of the rich man's power and the poor man's thraldom; but the genius of her seal was made by Wythe, the Roman figure of Virtue, clad as an Amazon, holding in one hand the spear of victory and in the other the sword of authority, and sternly republican in her motto of Sic Semper Tyrannis."

Beneath the Great Seal, which thus has found such fitting place upon the monument to George Wythe, the following inscription appears:

THIS TABLET IS DEDICATED

TO MARK THE SITE WHERE LIE

THE MORTAL REMAINS OF

GEORGE WYTHE.

BORN 1726—DIED 1806.

JURIST AND STATESMAN,

TEACHER OF RANDOLPH,

JEFFERSON AND MARSHALL,

FIRST PROFESSOR OF LAW

IN THE UNITED STATES,

FIRST VIRGINIA SIGNER OF THE

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE.

ERECTED BY

PATRIOTIC CITIZENS OF VIRGINIA,

A. D. 1922.This monument was erected at a cost of $785.00, through the co-operation of the Virginia Society of the Sons of the Revolution, the Sons of the American Revolution, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, and the Virginia

Page 44

State Bar Association. The memorial address was delivered by Mr. George Bryan, a distinguished member of this Association, and is with his permission printed in full as an appendix to this report.

It was to George Wythe that Patrick Henry alluded when he said in the Convention of 1775:

"Shall I light up my feeble taper before the brightness of his noontide sun? It were to compare the dull dewdrop of the morning with the intrinsic beauties of the diamond."[13]

He was, as his monument now proclaims, "The first professor of law in the United States," and it might have been added, "The second in the English-speaking world," as Dr. Tyler has pointed out—Sir William Blackstone, who filled the Vinerian chair of law at Oxford in 1758, being the first.

Not only was he the preceptor of Randolph, Jefferson and Marshall, but also James Monroe, St. George Tucker, Spencer Roane, James Breckenridge, John Coalter, Littleton Waller Tazewell, William Munford, James Innis, George Nicholas and Henry Clay. Mr. Clay said that "to no man was he more indebted, by his instructions, his advice, and his example, for the intellectual improvement which he made up to the period when in his twenty-first year he finally left the City of Richmond for Kentucky."[14]

In October, 1777, in the second year of the Commonwealth, an act was passed for establishing a High Court of Chancery. The first chancellors were Edmund Pendleton, George Wythe and Robert Carter Nicholas. It was by virtue of this office that George Wythe became a member of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, where in 1782 he delivered the celebrated opinion in "Commonwealth vs. Caton," in the course of which he said:

"Nay more, if the whole Legislature, an event to be deprecated, should attempt to overleap the bounds prescribed to them by the people, I, in administering the

Page 45

public justice of the country, will meet the united powers at my seat in this tribunal, and, pointing to the Constitution, will say to them, 'Here is the limit of your authority; and hither shall you go, but no further.'"

In 1788 the number of judges in the Court of High Chancery was reduced to one, and from that time until 1801 George Wythe was the sole Chancellor of the Commonwealth, with jurisdiction over the whole State.

Manifestly it was impossible to give in an epitaph even a summary of the achievements of a life so full of patriotic service, political honors and professional labors. It is enough that a reproach has been finally removed from the generations that have followed the noble Virginian by the erection of a simple monument to his memory. Let us leave him with the words of Thomas Jefferson ringing in our ears:

"No man ever left behind him a character more venerated than George Wythe. His virtue was of the purest tint; his integrity inflexible and his justice exact; of warm patriotism, and, devoted as he was to liberty, and the natural and equal rights of man, he might truly be called the Cato of his country, without the avarice of the Roman; for a more disinterested person never lived. Temperance and regularity in all his habits gave him general good health, and his unaffected modesty and suavity of manners endeared him to every one. He was of easy elocution, his language chaste, methodical in the arrangement of his matter, learned and logical in the use of it, and of great urbanity in debate; not quick of apprehension, but, with a little time, profound in penetration and sound in conclusion. In his philosophy he was firm, and neither troubling, nor perhaps trusting any one with his religious creed, he left the world to the conclusion that that religion must be good which could produce a life of such exemplary virtue.

"His stature was of the middle size, well formed and proportioned, and the features of his face were manly,

Page 46

comely and engaging. Such was George Wythe, the honor of his own time and the model of future times."[15]

- E. C. Massie,

- For the Committee.

GEORGE WYTHE—PIONEER.

Memorial Address at the Unveiling of the Monument Erected

at His Grave in St. John's Churchyard,

Richmond, Va., May 14, 1922.[16]By George Bryan, Esq., of Richmond.

Commonwealths, like individuals, are sluggish. They call it conservatism, but this is an excuse, not a reason. The tendency is towards inertia—towards the line of least resistance, but inertia means stagnation and ingrowing and consequent disintegration. If men and nations would live, they must resist. When the hour strikes, the pioneer comes to the front, announces his mission and begins his work.

In 1726 there was born in Virginia one whose memory we honor to-day—one who, upon reaching man's estate, looked about him and saw a large work to be done, a great wilderness to be conquered and paths blazed through it upon which men and women could walk to broader freedom, to real self-government and to purer ideals. Thomas Jefferson said of him that he was "the honor of his own and the model of future times"—that he truly might be called, "devoted as he was to liberty and the national and equal rights of man, the Cato of his country, without the avarice of the Roman."

An honored historian of this day and community, Dr. Samuel C. Mitchell has written of him: "In three several instances Wythe was a forerunner. As early as 1764 he wrote Virginia's first remonstrance to the House of Commons against the Stamp Act, taking so advanced a position in regard to that ominous measure as to alarm his fellow-Burgesses. He was perhaps the first judge to lay down, in 1782, the cardinal principle that a court can annul a statute deemed repugnant to the Constitution, thus anticipating by a score of years the classic

Page 47

decision of his great pupil, John Marshall, in Marbury v., Madison. He was an ardent advocate of the emancipation of slaves, actually freeing his own and making provision for them in his will. He was the first professor of law in the United States. In 1785 he wrote to John Adams, 'I have again settled in Williamsburg, assisting as professor of law and police in the University there, to form such characters as may he fit to succeed those which have been ornamental and useful in the national councils of America.' Either in his law office or as professor in William and Mary, he was the teacher of Jefferson, Marshall, Monroe, Clay and scores of others, only less prominent than these."

In the year 1806, at the age of eighty, he rested from his labors, but his works followed him. What are the lessons of such a life? They are many, but we have time to study only one. He was essentially a progressive of his day and generation. He was restless, uneasy, in the presence of oppression in any form, but, better than all else, he did not content himself, as do so many of us to-day, with expressing his dissatisfaction in a timid and formal way and returning at once to the farm or the merchandise or the study. He cried out against the Stamp Act, says Dr. Mitchell, so loud as to alarm his fellow-Burgesses—but, with a soul consumed with a passion for liberty, he cried the louder and tried to shame those conservative Burgesses into taking part in the work of rescuing the colony from the conditions which caused their alarm. He was a pioneer, a pathfinder, a forerunner—and his name shall ever be among the immortal ones of mankind.

The members of these patriotic societies honor themselves today by this tribute to the memory of "one of the simple, great ones gone"—though I cannot bring myself to add, "forever and ever by." I bring you this word of cheer—that I believe there are to-day in our midst men and women who, like George Wythe, can differentiate between a genuine and a spurious conservatism, who, confronted by entrenched oppression and evil in whatever form, will not be deterred by expressions of alarm, but will cry out yet the louder for a sane and substantial liberty—freedom from the domination of the dollar, of

Page 48

mob, of the dogma—the only liberty under which mankind can be free indeed.

In George Wythe liberty found a worthy champion. He was a State-builder—a nation-builder—and we to-day honor the memory of a great constructive force in this Republic.

Proceedings of the Virginia State Conference of the Daughters of the American Revolution, October 1922

Stated in the "Report of of State Historian" given by Mrs. Julia Little Pierce, the Commonwealth Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution reports the following activity:[17]

Page 59

On Revolutionary Day, May 24th, these societies [the Sons of the Revolution in State of Virginia, and the Sons of the American Revolution] and the William Byrd Chapter joined with us in services in old St. John's Church to commemorate the birthday of Patrick Henry and to unveil a tablet to George Wythe, the great Chancellor, and one of the Virginia Signers of the Declaration of Independence. Rev. Hugh Sublett conducted the ceremonies and Governor Trinkle, Dr. Freeman and Mr. George Bryan spoke. Passing out to the churchyard, a wreath was laid on the tablet by the Regent of the Chancellor Wythe Chapter.

The Chancellor Wythe Chapter also reports:

Chancellor Wythe: This Chapter was organized November 30, 1921, by Mrs. Manly B. Ramos with the State Regent, Dr. Barrett, present.

Several historical papers have been given at Chapter meetings and

Page 60

we attended the unveiling of the tablet to George Wythe in the churchyard of historic St. John's Church and placed a wreath of laurel and roses at the base of the monument in memory of the distinguished man for whom our Chapter was named.

See also

References

- ↑ National Intelligencer, and Washington Advertiser (Washington, D.C.), 15 December 1806, 2; Journals of the Council of Virginia, vol. 27, 448. Cited in Imogene E. Brown, American Aristides: A Biography of George Wythe (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1981), 301.

- ↑ William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, 10 December 1806, The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827, Library of Congress.

- ↑ W.P.P., "A Venerable Old Tree," The Times (Richmond, VA), October 28, 1894, 9; "In Wythe's Memory," The Times (Richmond, VA), January 12, 1901, 4.

- ↑ George Wythe Munford, The Two Parsons; Cupid's Sports; The Dream; and The Jewels of Virginia (Richmond, Virginia: J.D.K. Sleight, 1884), 429.

- ↑ An article in the Baltimore Sun on September 25, 1904, however, records that the grave was "shaded by an elm tree and identified by a piece of iron driven in at the head." Reprinted in Louise Pecquet du Bellet, Some Prominent Virginia Families (Lynchburg, VA: J.P. Bell, 1907) 2:24.

- ↑ The Enquirer (Richmond, VA), June 10, 1806, 3.

- ↑ "Report of Landmark Committee," Yearbook of the Virginia Association for the Preservation of Antiquities, 1898 and 1899, 29-30.

- ↑ Virginia State Bar Association Reports 32 (1920), 15-16.

- ↑ Reports, 1920, 19.

- ↑ Virginia State Bar Association Reports 33 (1921), 99.

- ↑ Sons of the Revolution in State of Virginia Quarterly Magazine (April, 1922), 38.

- ↑ Virginia State Bar Association Reports 34 (1922), 40-48.

- ↑ Daniel Call, "Biographical Sketch of the Judges," in Reports of Cases Argued and Decided in the Court of Appeals of Virginia, 2nd ed. (Richmond, VA: Robert I. Smith, 1833), 4:xiv.

- ↑ "Letter from Hon. Henry Clay to B.B. Minor, Esq.," Virginia Historical Register, and Literary Companion 5, no. 3 (July 1852), 162-167. Reprinted in B.B. Minor, ed., "Memoir of the Author," in Decisions of Cases In Virginia, By the High Court Chancery, with Remarks Upon Decrees By the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, by George Wythe (Richmond, Virginia: J.W. Randolph, 1852), xxxii-xxxvi.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, Notes for the Biography of George Wythe, August 31, 1820.

- ↑ The date of "May 14" is probably a typo, since the unveiling is stated to have been on May 24th in the same document and others.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Virginia State Conference of the Daughters of the American Revolution, October 11-13, 1922 (Charlottesville, VA: Surber-Arundale), 59-60.