Difference between revisions of "Hudgins v. Wrights"

m (Reverted edits by Lktesar (talk) to last revision by Mvanwicklin) |

m (→The Virginia High Court of Chancery's Decision) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==The Virginia High Court of Chancery's Decision== | ==The Virginia High Court of Chancery's Decision== | ||

| − | Chancellor Wythe concluded that all of the Wrights were various shades of white and thus entitled to their freedom. Furthermore, Wythe stated, "freedom is the birth-right of every human being" as indicated by the first article of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, "our political catechism".<ref>This article exists today as Article I, Section 1 of the Virginia Constitution, available at [http://constitution.legis.virginia.gov/ http://constitution.legis.virginia.gov/].</ref> Therefore, Wythe concluded, the burden is always on the person claiming ownership to prove that the other person can be bound by slavery. | + | [[George Wythe|Chancellor Wythe]] concluded that all of the Wrights were various shades of white and thus entitled to their freedom. Furthermore, Wythe stated, "freedom is the birth-right of every human being" as indicated by the first article of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, "our political catechism".<ref>This article exists today as Article I, Section 1 of the Virginia Constitution, available at [http://constitution.legis.virginia.gov/ http://constitution.legis.virginia.gov/].</ref> Therefore, Wythe concluded, the burden is always on the person claiming ownership to prove that the other person can be bound by slavery. |

==The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals' Decision== | ==The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals' Decision== | ||

Revision as of 16:05, 4 September 2018

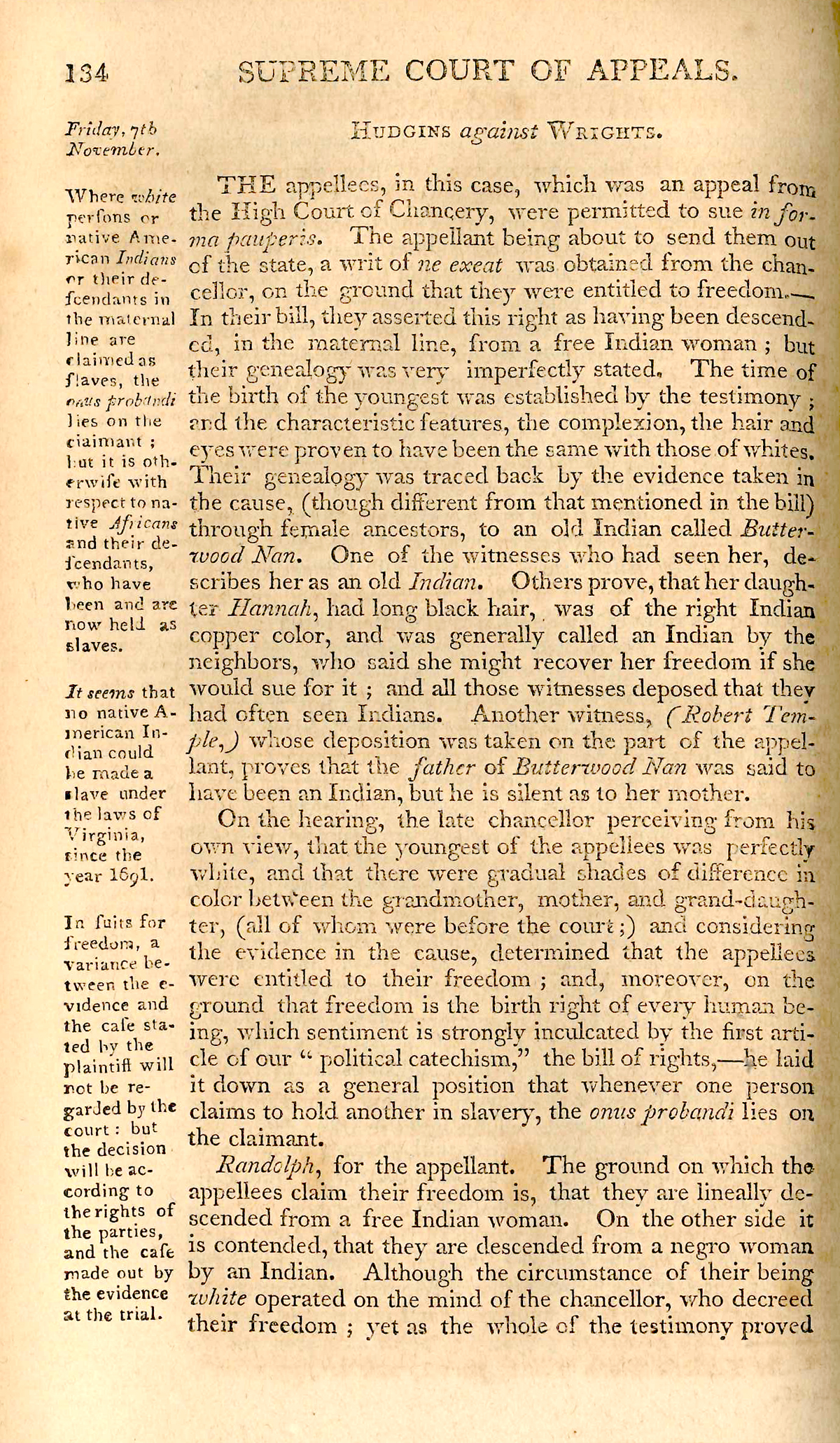

Hudgins v. Wrights, 11 Va. (1 Hen. & Mun.) 134 (1806),[1] was a case involving several slaves petitioning for their freedom and discussed who had the burden of proving whether they should be free or not. It also provides an illustrative example of the attitudes towards race that the members of Virginia society, even its highly-educated members, held during that time. It also shows an instance in which a progressive decision by Wythe was quickly diluted by Virginia's legal system.

Background

The Wrights were slaves owned by Hudgins. The Wrights said that they were entitled to freedom because they were descendants of a free American Indian woman. Hudgins contended that since the Wrights were descendants of an enslaved woman of African lineage and an American Indian man they were not permitted freedom from slavery.

The Virginia High Court of Chancery's Decision

Chancellor Wythe concluded that all of the Wrights were various shades of white and thus entitled to their freedom. Furthermore, Wythe stated, "freedom is the birth-right of every human being" as indicated by the first article of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, "our political catechism".[2] Therefore, Wythe concluded, the burden is always on the person claiming ownership to prove that the other person can be bound by slavery.

The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals' Decision

The Supreme Court agreed with the end result of Wythe's decision and declared that the Wrights were entitled to their freedom. The judges did not, however, agree with Wythe's reasoning.

Judge St. George Tucker, a student of Wythe's and his successor as William & Mary's professor of law and police, stated that the article from the Virginia Declaration of Rights that Wythe quoted "was meant to embrace the case of free citizens, or aliens only; and not by a side wind to overturn the rights of property, and give freedom to those very people whom we have been compelled from imperious circumstances to retain, generally, in the same state of bondage that they were in at the revolution, in which they had no concern, agency or interest."[3]

Tucker spent a couple of pages discussing the physical characteristics of American Indians and people of African descent, and to what extent those characteristics disappeared in generations of interracial descendants. Tucker concluded that the Wrights' physical appearance provided sufficient evidence that they were of American Indian, not African, descent, and the burden was therefore on Hudgins to prove otherwise, which Hudgins did not do. Judge Roane also concluded that the Wrights' appearance proved them to be of American Indian descent, and thus entitled to freedom under a 1691 statute,[4] unless Hudgins could prove otherwise.

The Court's official decree, issued after Wythe's death, said that the Court agreed with Wythe's conclusions on the Wrights' freedom and his rationale so far as it extended to "white persons and native American Indians",[5] but expressly disclaimed the rationale "so far as the same relates to native Africans and their descendants, who have been and are now held as slaves by the citizens of this state".[6]

See also

References

- ↑ William W. Hening and William Munford, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia (Philadelphia, PA: Smith and Maxwell, 1808), 1: 134. Note that this is the citation to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia's decision; Wythe's decision was not reported. This article is based on a summary of Wythe's decision contained in the Supreme Court's opinion.

- ↑ This article exists today as Article I, Section 1 of the Virginia Constitution, available at http://constitution.legis.virginia.gov/.

- ↑ Hudgins v. Wrights, 141 (emphasis in original).

- ↑ Act IX, "An act for a free trade with Indians", in William W. Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia (Philadelphia, PA: Printed for the editor by Thomas Desilver, 1823), 3: 69.

- ↑ Hudgins v. Wrights, 144 (emphasis in original).

- ↑ Ibid. (emphasis in original)

External links

- "Hudgins v. Wright" on Wikipedia.

- Vernellia Randall, "Hudgins v. Wrights (1806)," Law 6892—Race and Racism in American Law, University of Dayton School of Law.

- St. George Tucker, "Hudgins v. Wright Case Material," Box 71, Tucker-Coleman Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.