Pendleton v. Whiting

Pendleton v. Whiting, Wythe 38 (1791), was a case that discussed whether the duty a beneficiary owed an executor was subject to the statute of limitations.[1]

Background

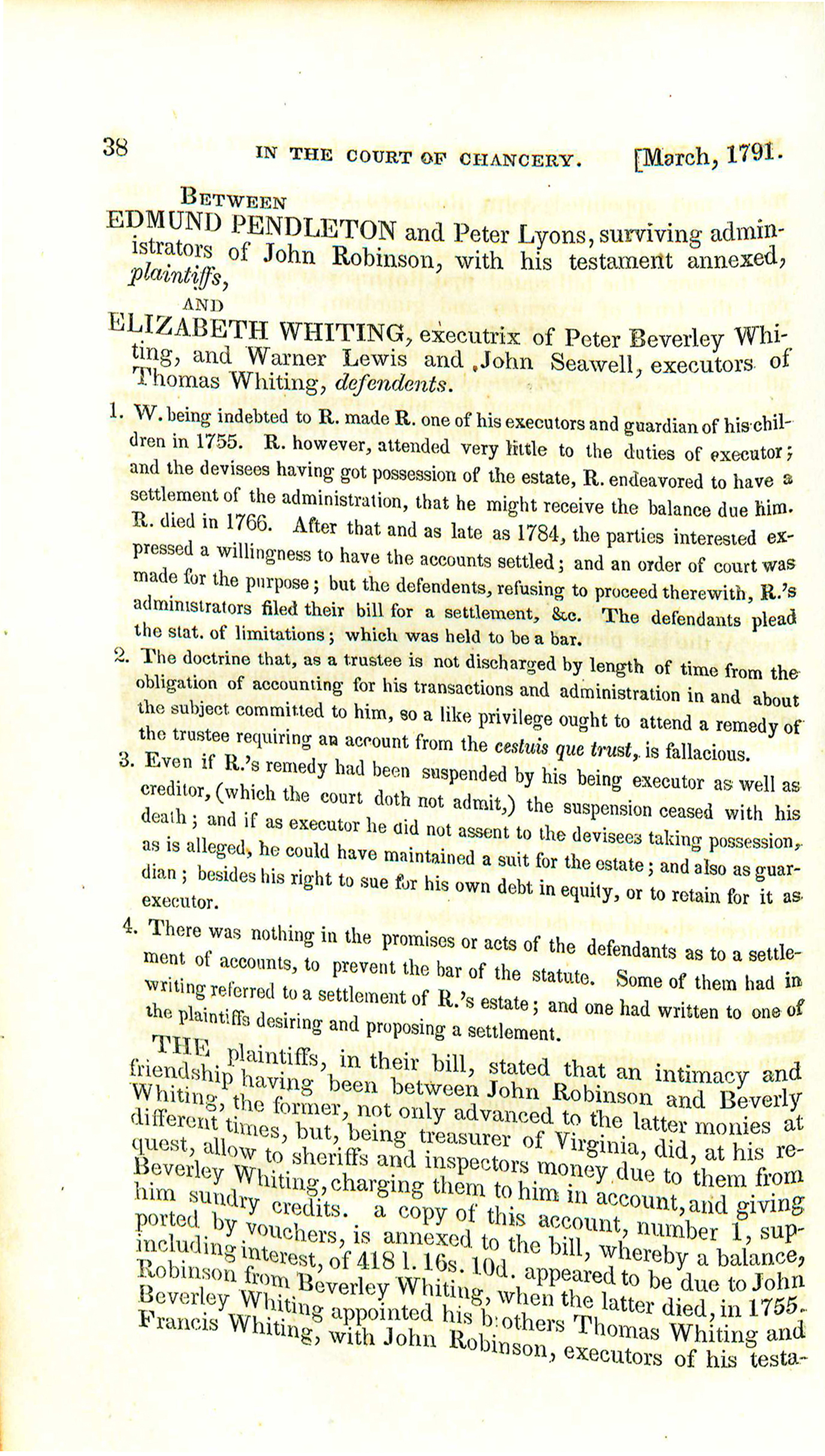

Edmund Pendleton and Peter Lyons filed suit as the administrators of John Robinson's estate. The defendants were Elizabeth Whiting, Warner Lewis, and John Seawell, who were acting as executors for Beverley's sons, Peter Beverley Whiting and John Whiting. Robinson had paid several creditors on behalf of his friend Beverley Whiting; when Beverley Whiting died in 1755, his estate owed Robinson over £418. Beverley Whiting named Robinson his estate's executor, along with Beverley Whiting's brothers, Thomas and Francis. Thomas and Francis claimed possession of their share of Beverley Whiting's estate before Robinson's debt was repaid. Robinson scheduled several meetings with Thomas to settle the debts that Beverley Whiting's estate owed Robinson, but they never successfully met to discuss the topic, and Robinson died in May 1766.

Various efforts to settle Beverley Whiting's debt with Robinson were stymied by Thomas's failure to attend meetings organized for that purpose, and then the American Revolution stopped judicial business in Virginia. Thomas Whiting died, and in 1783 Robinson and Lyons asked Elizabeth Whiting about the status of the debt. In January 1784, Elizabeth petitioned the Gloucester County Court to appoint commissioners to settle the debt between Thomas's estate and Robinson's estate, but then refused to proceed because she had been advised that Pendleton's and Lyons's claims were barred by the statute of limitations. Pendleton and Lyons argued that just as a trustee's duty to their beneficiary never expires, equity demands that a duty the beneficiary owes to the trustee should not be subject to the statute of limitations.

The Court's Decision

The High Court of Chancery dismissed Pendleton's and Lyons's claims as time-barred by the statute of limitations, stating that it was a logical fallacy to claim that a beneficiary's duty to the trustee should be equally immune to the statute of limitations as a trustee's duty to the beneficiary; the property a trustee holds in trust legally belongs to the beneficiary, and thus a special fiduciary duty applies in ensuring that the property is given to the beneficiary. No such fiduciary duty applies to a debt the beneficiary owes the trustee. The law presumes that if a person has not taken legal action to recover property within a certain period of time, then that person has abandoned their claim to the property. This presumption, the court stated, is even stronger in the case of an executor such as Robinson, who had the power to claim payment on his debt from Beverley Whiting's estate, but failed to do so before Beverley Whiting's sons took possession of the estate's property.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 38.