Hearne v. Roane

Hearne v. Roane, Wythe 90 (1790), was a case involving a dispute over the size of an inheritance.[1]

Background

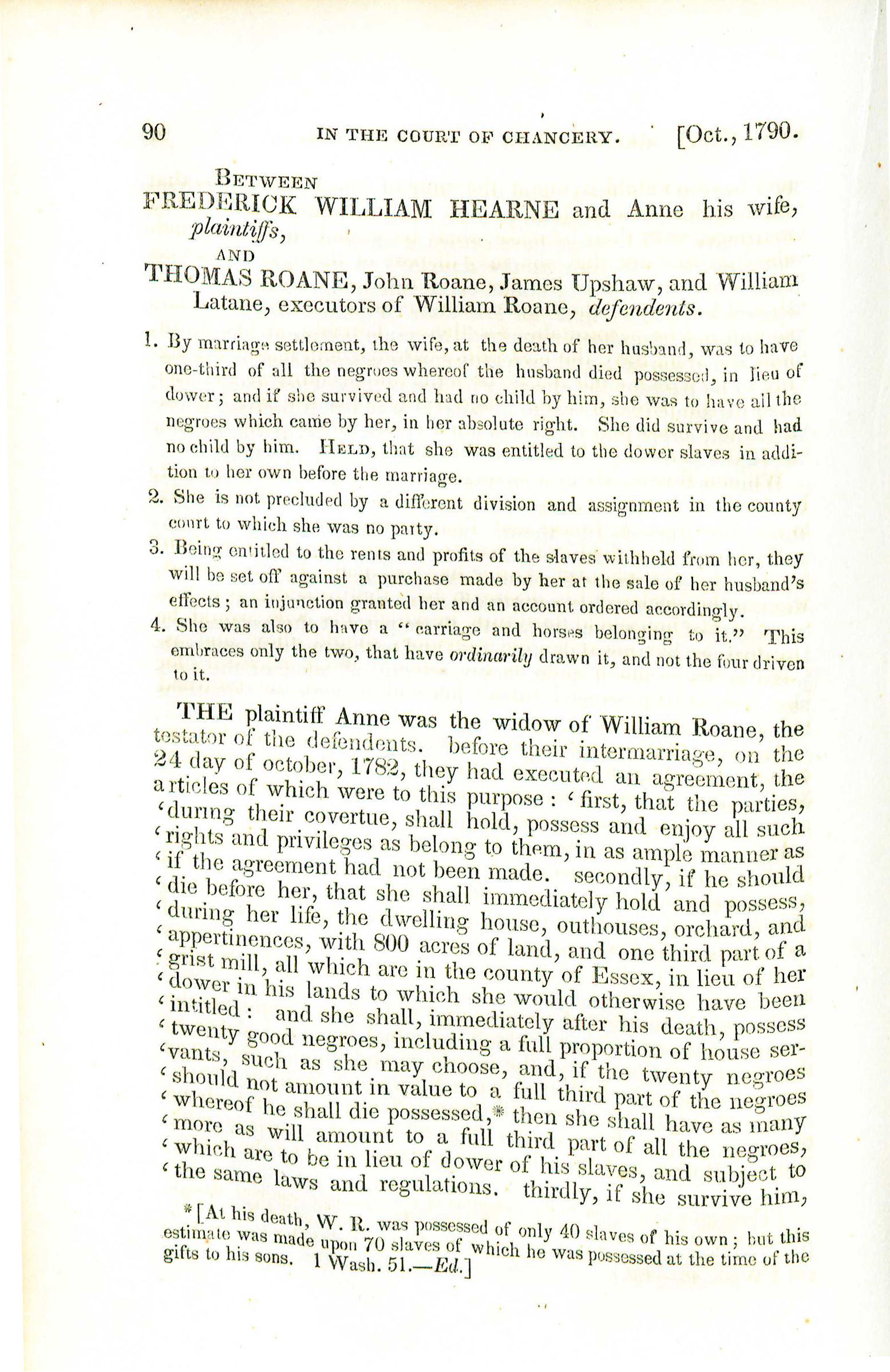

When plainiff Anne Hearne married William Roane, the marriage contract stated that if Roane were to die before Hearne, Hearne would receive either twenty or one-third of the total of Roane's slaves, whichever was greater. Furthermore, the contract stated that if Roane were to die before Hearne and Hearne had no living children at the time, the slaves that were added to Roane's holdings as a result of his marriage to Hearne would be given to Hearne. These provisions, the contract said, were to be in lieu of Hearne's dower. The contract also stated that Hearne would get "the best riding carriage, and horses belonging to it" on Roane's death, as well as one-third of Roane's personal estate.

Upon Roane's death, the defendants, the executors of his estate, filed an ex parte motion to appoint commissioners to value, assign, and divide the slaves. The commissioners awarded Hearne nineteen slaves, some of which had been hers before she married Roane. Hearne also bought numerous items at a sale of Roane's personal estate for £368. Hearne filed a bill with the High Court of Chancery claiming dower, the slaves Hearne had owned pre-marriage, compensation for two of the estate's four carriage horses (because the defendants had sold two and Hearne claimed she was entitled to all four), and reimbursement for the £368 she paid for items from Roane's personal estate. The defendants argued that the marriage contract nullified any claim Hearne had of dower, that only two horses belonged to the carriage, and that the entirety of Roane's personal estate, including the items Hearne bought, did not cover the debts Roane's estate owed.

The Court's Decision

The High Court of Chancery found that the slaves Hearne owned before marrying Roane should not have been included when calculating what one-third of Roane's slaves amounted to. The Court found that since the slaves were Hearne's property at the time the marriage contract was formed, and that they were her property when Roane died and left Hearne childless, they were not Roane's property to dispose of and therefore not subject to the law of dower. The Court also stated that Hearne should not be subject to a decree that issued from a hearing she was not party to. The Court also found that since only two horses were normally used to draw the carriage, only two horses "belonged" to the carriage for purposes of the contract, and so Hearne was only entitled to two carriage horses.

The Court awarded Hearne eleven slaves on top of the nine surviving slaves she owned before the marriage, for a total of twenty, and ordered the defendants to compensate Hearne for the profit from the extra slaves she was owed from the time of Roane's death. The Court also ordered an accounting of the estate to determine if there was a surplus remaining that could be used to compensate Hearne for the money she spent on items at the sale of Roane's personal estate.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 90. The defendants appealed the High Court of Chancery's decision to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, which upheld the decision in Roane's Executors v. Hern, 1 Va. (1 Wash.) 47 (1791).