Cole v. Scott

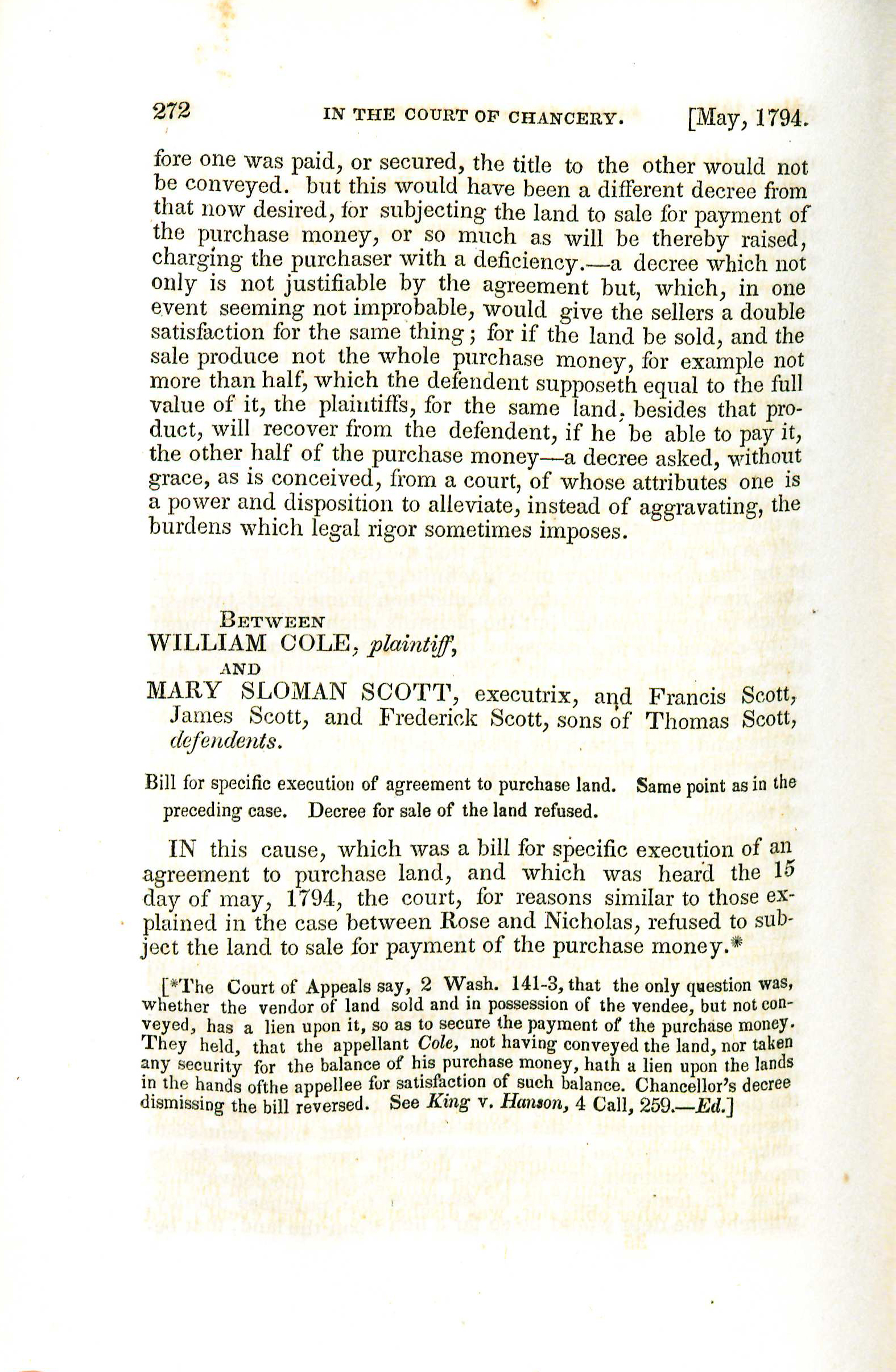

Cole v. Scott, Wythe 272 (1794),[1] was about whether a court of equity could require the sale of land by the purchaser to satisfy the purchase price, even though that requirement was not in the original contract.

Background

Cole sold land to Scott. Scott possessed the land (i.e., exercised control over it), but Cole had not yet given legal title in the land to Scott, and Scott had not paid Cole the purchase price.[2] Cole filed a bill with the High Court of Chancery asking it to enforce specific performance of the contract (i.e., requiring both sides to perform their duties as the contract required), and to force a sale of the land to raise funds for the purchase price.

The Court's Decision

The High Court of Chancery's decision was one sentence long. Wythe said that the principles he used to decide Rose v. Nicholas also applied here, and denied Cole's request to force a sale of the land.

Cole appealed to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, which reversed the Chancery Court's decision.[3] The Supreme Court stated that the established law[4] was that a seller of land still has a lien upon that land so long as they have not transferred legal title to the purchaser and the purchaser has not given the seller any security (such as a bond) for the purchase price. Therefore, a court in equity can force a sale of the land to satisfy the purchase price.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852): 272.

- ↑ Reading the Supreme Court of Appeal's opinion, it appears that Scott did not have enough funds to pay the listed price.

- ↑ Cole v. Scot, 2 Va. (2 Wash.) 141 (1795).

- ↑ Justice Roane cited an English case, Blackburn v. Gregson, 28 Eng. Rep. 1215, 1 Bro. C. C. 420 (1785); and a Virginia case, King v. Hanson, 8 Va. (4 Call.) 259 (1790). President Pendleton and Justice Fleming merely stated that the law was settled.