Pendleton v. Lomax

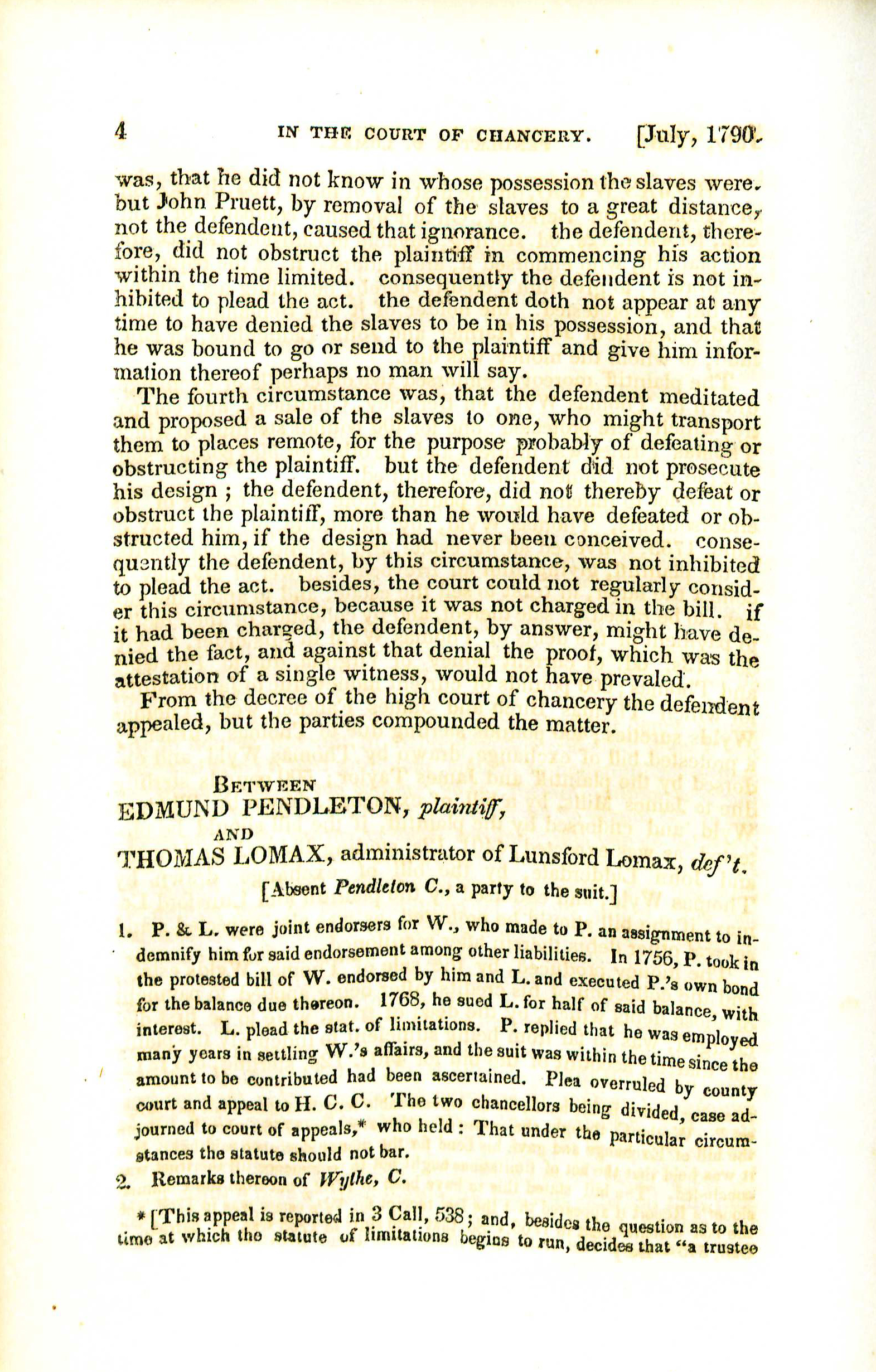

Pendleton v. Lomax, Wythe 4 (1790),[1] ???, Lomax v. Pendleton, 7 Va. (3 Call) 538 (1790)[2] was a case originally appealed to the High Court of Chancery from the Caroline County Court. The plaintiff was one of the chancellors, however, and the remaining two chancellors split, so the case was transferred to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia.

Background

In May 1753, Edmund Pendleton signed with Lunsford Lomax as co-sureties on a bill of exchange for debts incurred by Thomas Wyld. In exchange, in June 1753, Wyld gave Pendleton the power of attorney to sell Wyld's estate in trust and to collect on all debts due Wyld in order to repay the debts Wyld owed others. The sale of Wyld's estate and collection of debts owed Wyld were not nearly enough to cover Wyld's debts; Wyld still owed £531 to creditors. In November 1756, Wyld's creditor made a claim on the bill of exchange, and Pendleton gave his own bond to the creditors to settle Wyld's debt.

In 1766, Pendleton demanded Lomax pay one-half of the remaining debt that Pendleton had given a bond for. Lomax refused to pay, so Pendleton sued in 1768. Lomax moved to dismiss, claiming that the statute of limitations had expired; Pendleton claimed that the process of selling Wyld's estate, and thereby establishing how much of Wyld's debt remained after the sale, caused the delay in filing suit, and that therefore his case was not time-barred. While the case was in county court, Lunsford Lomax died, and Thomas Lomax, the estate's administrator, took Lunsford's place as defendant. The county court rejected Lomax's statute of limitations claim, and Lomax appealed to the High Court of Chancery.

Chancellor Pendleton did not hear the case, as he was on the other side of the bench as the plaintiff. One of the chancellors held that Pendleton's cause of action originated in November 1756 when Pendleton gave his bond for Wyld's remaining debts, meaning that the statute of limitations barred Pendleton's cause of action. The other chancellor was leaning towards allowing Pendleton's suit to proceed.[3] The High Court of Chancery appeared to be headed towards a split decision, so they referred the case to the Supreme Court of Appeals.

The Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Appeals held that the statute of limitations did not bar Pendleton's cause of action.

Wythe's Discussion

Wythe stated that Pendleton's cause of action began when he issued a note in November 1753 to Wyld's creditors erasing Wyld's debt. In Wythe's view, Wyld's transfer of his estate and accounts receivable to Pendleton, and Pendleton's sale of Wyld's property, had nothing to do with Lomax. In fact, Wythe continues, nothing in the record indicated that Lomax knew that a claim had been made on the bill of exchange until Pendleton took action in 1766 to recover half of the debt. Under such circumstances, Wythe wryly stated, "the plea of the statute for limitation of actions in this case would be thought by some to be a legal and conscientious defense, if better judges had not determined the contrary."[4]

Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe

Justinian's Codex

Quotation in Wythe's opinion:

Cum alter ex fideiussoribus in solidum debito satisfaciat, actio ei adversus eum qui una fideiussit non competit. Potuisti sane, cum fisco solveres, desiderare, ut ius pignoris quod fiscus habuit in te transferretur, et si hoc ita factum est, cessis actionibus uti poteris. quod et in privatis debitis observandum est. C. l. VIII. tit. XLI. l. XI. [5] Translation: When one of two guarantors satisfies the debt in full, an action for him against the one who co-guaranteed does not exist. Certainly you are able, when you loosen the treasury, to request that the right of pledge which the treasury holds, is transferred unto you, and if it is done in this way, you will be able to make use of the conceded actions, which also is observed in private debts.

Justinian's Digest

Quotes in Wythe's opinion:

...(b) for, in the first case, the creditor, when he received his money from the surety non in solum accepit, did not receive payment... Translation: Not accepted as freeing [the debtor from obligations to the creditor].[6]

Fideiussoribus succurri solet, ut stipulator compellatur ei, qui solidum solvere paratus est, vendere ceterorum nomina. Dig. l. XLVI. tit. 1. l. XVII. Translation: It is customary to give aid to guarantors, so that the stipulator is compelled to sell the names of others [i.e. other debts he might be owed] to him, who is prepared to pay the debt.[7]

Cum is, qui et reum et fideiussores habens, ab uno ex fideiussoribus, accepta pecunia praestat actiones, poterit quidem dici nullas iam esse: cum suum perceperit, et perceptione omnes liberati sunt, sed non ita est, non enim in solutum accipit, sed quodammodo nomen debitoris vendidit, et ideo habet actiones, quia tenetur ad id ipsum, ut praestet actiones. Dig. lib. XLVI. tit. 1. l. XXXVI. Translation: When someone, who, having both a debtor and guarantors, with money having been accepted from one of the guarantors, hands over his actions, it could certainly be said that now there is nothing, since he will have received his [debt] all are free by his reception. But it is not thus: for he did not receive it in a free manner, but, as it were, he sold the name of the debtor [i.e. the account], and still has the actions, because he is bound to that himself, so he might transfer the actions.[8]

For these quotes, Wythe most likely used his copy of the Corpus Juris Civilis which includes the Digest of Justinian.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 4.

- ↑ Daniel Call, Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia (Richmond: A. Morris, 1854): 3:538. George Wythe owned the first edition of this set.

- ↑ In his account of the case, Wythe does not state which chancellor held each point of view, simply referring to "another" and "the third judge". Wythe's remarks on the opinion, however, offer some useful hints as to where Wythe's thought lay.

- ↑ Wythe 9.

- ↑ Ibid, 8.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.