"Memoranda Concerning the Death of Chancellor Wythe"

The "Memoranda Concerning the Death of Chancellor Wythe," also known as the Dove Memo, is a short statement of the recollections of Dr. John Dove of Richmond, VA, recorded by Thomas Hicks Wynne. The memorandum is dated September 16, 1856, and contains Dove's version of the events surrounding the death of George Wythe, and subsequent murder trial.[1]

In several respects, Dove's memorandum is an untrustworthy source. It was recorded when Dr. Dove was sixty-four years old—fifty years after the events of 1806 which it describes: at the time of Wythe's death John Dove would have been a young man of fourteen. The memo contains several historical inaccuracies, and reliable evidence undermines the believability of its specific allegations: in particular the claims that Wythe's grand-nephew, George Wythe Sweeney, poisoned Wythe accidentally; and that Wythe had a son, Michael Brown, with his housekeeper Lydia Broadnax. Despite its unreliable nature, the assertions made in the Dove Memo continue to be repeated, often without attribution.

Contents

Text of the memorandum

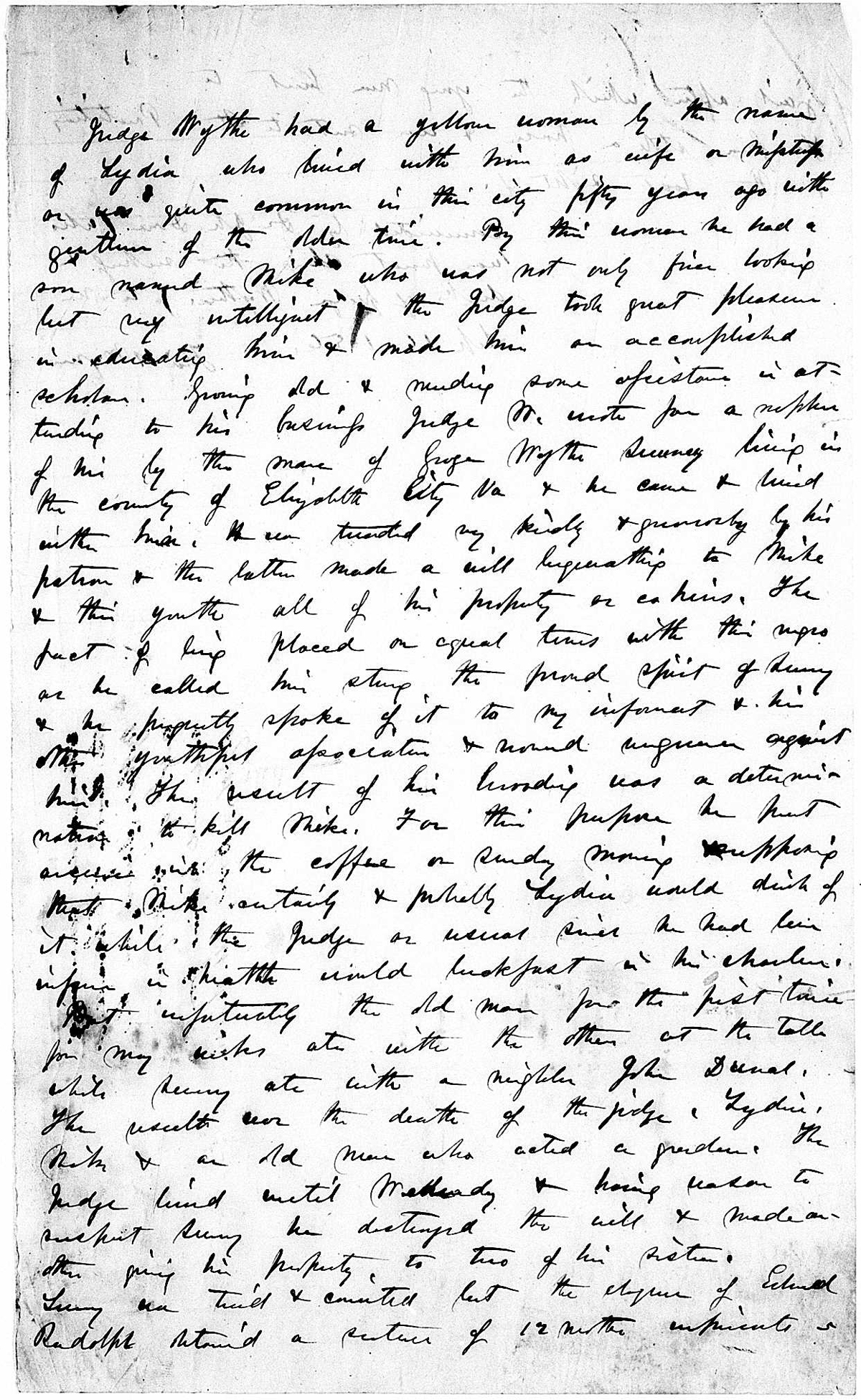

Page 1

1856

Sep 16

Wynne, Thomas Hicks

Memorandum concerning

the death of George

Wythe

Page 2

Judge Wythe had a yellow woman by the name of Lydia who lived with him as wife or mistress as was quite common in the city fifty years ago with gentlemen of the olden time. By this woman he had a son named Mike who was not only fine looking but very intelligent & the Judge took great pleasure in educating him & made him an accomplished scholar. Growing old & needing some assistance in attending to his business Judge W. wrote for a nephew of his by the name of George Wythe Sweeney living in the county of Elizabeth City Va & he came & lived with him. He was treated very kindly & generously by his patron & the latter made a will bequeathing to Mike & the youth all of his property as co heirs. The fact of being placed on equal terms with the negro as he called him stung the proud spirit of Sweeney & he frequently spoke of it to my informant & his other youthful associates & vowed vengeance against him. The result of his brooding was a determination to kill Mike. For this purpose he put arsenic in the coffee on Sunday morning supposing that Mike certainly & probably Lydia would drink of it while the Judge as usual since he had been infirm in health would breakfast in his chamber. But unfortunately the old man for the first time for many weeks ate with a neighbor John Duval. The result was the death of the judge, Lydia, Mike, & an old man who acted a gardener. The judge lived until Wednesday & having reason to suspect Sweeney he destroyed the will & made an other giving his property to two of his sisters. Sweeney was tried & convicted but the eloquence of Edmund Randolphe returned a sentence of 12 months [? ? ?] in

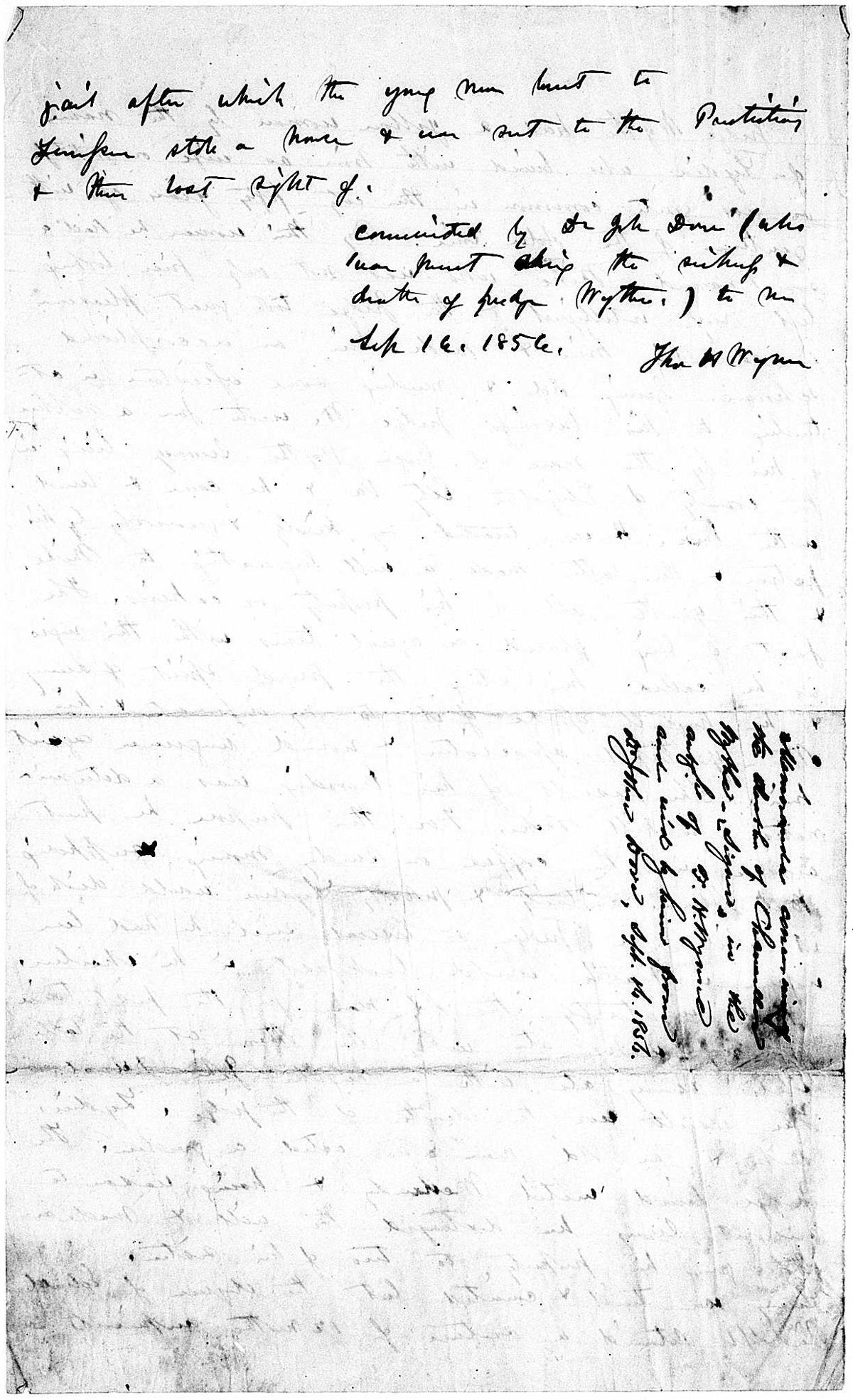

Page 3

jail after which the young man went to Tennessee stole a horse & was sent to the penitentiary & then lost sight of.

Communicated by Dr. John Dove (who

was present during the sickness &

death of Judge Wythe) to me

Sep 16, 1856.

Thos H Wynne

Memoranda concerning

the death of Chancellor

Wythe—Signed in the

autgh. of T.H. Wynne

and rec'd by him from

Dr. John Dove, Sept. 16, 1856.

Analysis

The story told by the Memo differs significantly from that of other primary sources. According to the Memo, Wythe lived with “a yellow woman by the name of Lydia,” who was his “wife or mistress,” and together they had a son, Mike, whom Wythe “took great pleasure in educating.” Requiring additional assistance because of his age, Wythe then called for his nephew, George Wythe Sweeney, who also came to live with him. However, Sweeney became jealous, and his pride was hurt, when he discovered that Wythe had written both Sweeney and Mike into his will as co-heirs. As a result, Sweeney decided to kill Mike. To this end, he put arsenic into the household’s morning coffee, with the intention that Mike would drink it, but that Wythe, who was ill and had taken to eating his breakfast in his chambers, would not have any of the poisoned drink. By chance, however, Wythe, did leave his room in order to have breakfast with a neighbor, John DuVal, and was poisoned. Also poisoned were Mike, Lydia, and “an old man who acted as gardener,” and all died as a result. Before he died, Wythe wrote Sweeney out of his will and left his property to Sweeney’s sisters instead. After Sweeney was acquitted, he left Virginia for Tennessee, where he “stole a horse and was sent to a penitentiary and then lost sight of.”

Wythe did have a housekeeper named Lydia Broadnax, a freed black woman, and he was educating a free black teenager named Michael Brown. All three were poisoned when Wythe’s grand-nephew, George Wythe Sweeney, put arsenic in the Sunday morning coffee pot on May 25, 1806. Wythe and Brown both died of the poison. Sweeney was indicted and tried for murder, and acquitted. Brown and Sweeney were beneficiaries of Wythe’s will, and that document was almost certainly a central motivation for the murders. In all other respects, however, the details recounted by the Dove Memo have no other historical support outside the Memo itself and often contradict other primary sources.

Dr. John Dove was born in Richmond, Virginia, on September 2, 1792.[2] He practiced medicine in Richmond from at least 1824 until 1853, during which time he was a member of the Medical Society of Virginia and the first President of the short-lived Medico-Chirurgical Society of Richmond City.[3] Dove also sat on the City Board of Health and was a member of the Board of Trustees of Hampden-Sidney College.[4] In addition to his successful medical practice, he was a member of the City Council and a prominent Mason.[5] He served as Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of Virginia for fifty-four years, making him at the time of his death the oldest Grand Secretary in the United States.[6] Dove died on November 16, 1872, at his home in Richmond, at the age of 85.[7]

In addition to telling his story to Thomas Wynne, Dove related a similar narrative to Benjamin Blake Minor. Minor references Dr. Dove in a footnote to his "Memoir of the Author" a biography Minor included in his edition of Wythe’s Decisions of Cases in Virginia, published in 1852. The footnote reads, in relevant part:

At the time of the poisoning, the Chancellor had been confined at home by indisposition. Swinney, indignant at the kindness and munificence of his uncle to the colored boy, intended to poison the boy, and put the poison in the coffee for breakfast, not expecting the Chancellor would think of coming from his chamber, or would be in any danger of partaking of it. But during his absence, the Chancellor did make his appearance and drank of the coffee. The woman [Lydia Broadnax] also died. These facts were obtained from Dr. John Dove, who then resided in that neighborhood, and was present when Mr. Wythe breathed his last.[8]

The version of events that Minor relates here matches that of the Dove Memo, but gives fewer details. Both accounts attributed to Dove claim that Wythe was ill before the poisoning occurred; that his death was an accident while Michael Brown’s was planned; that Sweeney was motivated by anger and that he was jealous of Brown’s place in Wythe’s household, as well as in his will; and that Broadnax died of the poison as well as the other victims. Minor’s footnote does not mention the Dove Memo’s allegation of a family relationship among Wythe, Lydia Broadnax, and Michael Brown.

Allegations

The claims asserted in the Dove Memo are almost certainly false. The origins of the Memo itself raise serious suspicions about its trustworthiness. The text of the Memo also includes blatant historical inaccuracies. Finally, other available evidence contradicts the Memo’s assertions that Wythe’s death was accidental, and that Michael Brown was Wythe’s son with Lydia Broadnax.

Even at glance, the Memo does not appear to be a trustworthy primary source. It is dated 1856, 50 years after Wythe’s death in 1806. If one assumes that Dove was present at Wythe’s death, his recollection half a century later is likely not as reliable as contemporary accounts of the 1806 events. In addition, there is reason to doubt that Dove ever had first-hand knowledge of those events at all. No Dr. Dove is listed among the doctors attending at Wythe’s death,[9] nor is any John Dove mentioned "in any capacity" in any of the "extensive testimony" presented at Sweeney’s indictment.[10] This is not likely an inadvertent omission, as John Dove was only 14 in 1806.[11]

John Dove may have had reason to spread scandalous and false rumors about Wythe by claiming that he had a relationship with one of his former slaves. The Virginia tax lists record that a certain property in Richmond changed hands frequently between 1805 and 1809, alternately owned by the estate of James Dove and by Wythe and his estate.[12] Such a rapid "alteration of ownership suggests that the property in question may have been the object of litigation" between the Dove family and the Wythe estate.[13] Dove may have been thinking about this past disagreement when he recounted his version of the events surrounding Wythe’s death.[14]

In his essay "The Murder of George Wythe", Julian Boyd advances another theory to explain the claims made by Dr. Dove, and in particular the allegation that Wythe’s death was accidental rather than premeditated.[15] In Dove’s version of events, Sweeney killed Michael Brown because discovering that he and Brown were "co-heirs" to, and thus equal in, Wythe’s will wounded his pride. Anger, as much as greed, inspired him to kill, and Wythe was an unintended casualty of that anger. Particularly on the eve of the Civil War, "it may have seemed best to those who wrote about this case to make its motive depend solely upon the racial animus developed through granting too much freedom to Negroes."[16] This theory of Sweeney’s motive, which seems to have its origin with Dr. Dove,[17] would have emphasized the dangers of manumission, at the same time as it made any discussion of the suppression of evidence from black witnesses at Sweeney’s trial unnecessary.[18] If Wythe’s death was an accident, Sweeney was acquitted not because of any defect in the judicial process, but because he truly was innocent of murder.[19]

In addition to the suspicious origins of the Memo, its text includes several blatant historical inaccuracies, which render the rest of its allegations less credible. For example, it claims that not only Wythe and Michael Brown, but Lydia Broadnax and "an old man who acted as gardener" died of the poison.[20] This gardener, Benjamin, was another of Wythe’s former slaves, and was already deceased by 1806.[21] The Memo also misidentifies William DuVal as John Duval and asserts that Wythe ultimately left his property to Sweeney’s sisters.[22] The Memo’s narrative of accidental poisoning specifically relies on its claim that Wythe had been ill for some time as of May 26, and so not in the habit of breakfasting with the family, and unlikely to be a victim of Sweeney’s poisoning. But this is also false: Wythe was not ill on the day he was poisoned.[23] Generally, because the Memo is "replete with provable errors," it "must be considered wholly suspect."[24]

Other available evidence, as well as common sense considerations, undermines the believability of both significant Dove Memo allegations: that Wythe’s death was accidental, and that Lydia Broadnax was Wythe’s mistress and Michael Brown their son.

According to the Memo, Sweeney only meant to kill Michael Brown and did not anticipate that Wythe would also drink the poisoned coffee. But this version of the events does not account for all of the circumstances of Wythe’s death. First, the Dove Memo narrative does not take into account all of Sweeney’s likely motives for committing murder.[25] Only by killing Wythe specifically could Sweeney avoid arrest for forging checks in his grand-uncle’s name, as he had been doing.[26] In addition, only at Wythe’s death would the provisions of his will go into effect, allowing Sweeney to benefit financially from his crime.[27] Assuming that Sweeney intended to kill Wythe as well as Brown provides a simpler and more logical explanation for his actions because "[w]ith one blow he would solve all his problems: he would prevent his forgery from being discovered, he would get Michael’s share of the estate, and he would receive his inheritance immediately."[28]

Second, all other witnesses to the events surrounding Wythe’s death believed him to have been murdered.[29] Wythe himself professed "I am murdered!" while on his death bed, and after Michael Brown’s death, he changed his will to disinherit Sweeney, implying that he suspected his grand-nephew of the crimes.[30] Contemporary letters from Wythe’s friends, including William DuVal and Thomas Jefferson, "make no ... distinction" between the two deaths.[31] Even the grand jury indicted Sweeney for two counts of murder; although he was eventually acquitted, "the grand jury [was] convinced that both victims had been put to death with premeditation."[32]

The Memo’s contention that Lydia Broadnax was Wythe’s mistress, and Michael Brown their son, is similarly untenable when put into context. First, it is unlikely that Broadnax was Wythe’s mistress. Although she continued to work as his housekeeper after he freed her, she was living in a separate house in Richmond by 1797 and even taking in boarders there.[33] She was not part of the Wythe household.[34] She also hired herself out to work to other employers, "which she hardly would have done had she been Wythe’s mistress."[35]

It is even less likely that Broadnax was Brown’s mother. Brown was probably born in 1791, when Lydia was around fifty years old.[36] References to her in contemporary documents emphasize her age: she is called the “old negro woman,” “old Lydia,” and “old cook Lydia,” by several people, including by Henry Clay.[37] Clay would have known Broadnax at around the time that, according to the Dove Memo, she gave birth to Brown.[38] She and Brown also have different last names, and no primary source refers to Brown as her son or makes any mention of a family relationship between them.[39]

There is no contemporary reference or documentation supporting either the supposition that Broadnax was Wythe’s mistress or that Brown was their son. Even at the time of Wythe’s death, none of the fourteen witnesses who testified about the poisoning at Sweeney’s indictment referenced this particular story, and no newspaper made mention of the gossip.[40] This is probably not a coincidental or accidental omission, as Wythe would have had difficulty keeping a mistress and son so completely hidden from his friends and family.[41]

Without any evidence reasonably linking Broadnax to Brown or Broadnax to Wythe, little remains in support of the assertion that Wythe was Brown’s biological father. Only Wythe’s obvious generosity to and care for Brown, for example, in educating him, including him as a beneficiary in Wythe’s will, and arranging for Thomas Jefferson to continue his education after Wythe’s death, might still lead one to believe that Brown was secretly Wythe’s son. However, even this evidence becomes less convincing when seen in context. Wythe provided Brown with an education, but this was in keeping with his other anti-slavery beliefs and his "benevolence to African-Americans."[42] He had taught at least one of his former slaves, Jimmy, to read and write, and eventually freed not only Jimmy, but most of his other slaves as well.[43] No one has suggested that Wythe was Jimmy’s biological father.[44] By teaching Brown as he would a white student, Wythe planned to show that black people were equally capable of being educated as were their white counterparts.[45]

That Wythe included Brown in his will is also not particularly strange, nor unexplainable absent the speculation that Brown was his son. Wythe also provided for his former slaves Lydia Broadnax and Benjamin. These inheritances may simply have reflected Wythe’s knowledge that Brown, Broadnax, and Benjamin would have difficulty surviving without assistance after his death.[46] Generally, "[i]t seems likely that Wythe left his possessions to these [former] slaves to ensure that they would not drift back into servitude, and out of appreciation for the fact that, though they were free, they were devoted enough to stay with him and care for him in his old age."[47]

The Dove Memorandum, written 50 years after Wythe’s death, containing multiple historical inaccuracies, and presenting a version of events that makes little sense when put into a broader context, is not a trustworthy document in any sense.

Influence

Although the Memo seems "to be gossip and has been generally discredited,"[48] some of its claims continue to be repeated even in modern scholarship on Wythe’s life and the events surrounding his death. Its allegation that Lydia Broadnax was Wythe’s mistress and Michael Brown their son has been particularly pervasive, probably because the same story was told by Fawn Brodie in her 1974 book Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History. The Dove Memo is also one of only two primary sources that hints at what Sweeney’s life after his acquittal. The other, Minor’s reference in "Memoir of the Author," may also have been based on information provided by Dr. Dove.

Wythe's death as accidental

According to the Memo, Sweeney only intended to kill Michael Brown, and did not plan for Wythe to drink the arsenic-laced coffee. In other words, Wythe’s death was not a murder, but an accident. This narrative was still repeated into the early twentieth century, for example in the sketch of Wythe in Great American Lawyers (1907) and in the entry on Wythe’s life in the Dictionary of American Biography, published between 1920 and 1936.[49] In Great American Lawyers, Wythe’s death is reported as an accident, and Sweeney’s plan is characterized as an attempt to gain access to Michael Brown’s portion of the inheritance by murdering him: "Avarice overpowered the favorite nephew, and to get immediate possession of the devise, he put arsenic in a pot of coffee which he supposed the Negro boy would be the only one to use. But it happened that Judge Wythe also drank of the coffee, and both were fatally affected."[50] The account of events offered in the Dictionary of American Biography is more tentative, but essentially the same: "To secure [Michael Brown’s] legacy, or perhaps the inheritance, Sweeney, who was apparently in financial difficulties, poisoned some coffee with arsenic. The servant drank some; Wythe also drank some, perhaps fortuitously."[51] Despite the use of the uncertain qualifier "perhaps," the author of the dictionary entry does give some credence to the story given in the Dove Memo.[52]

The accidental poisoning theory, however, can be found neither in 1806 sources, nor in modern accounts of the events surrounding Wythe’s death. This "alteration" in the story "cannot be traced back beyond 1850."[53] Today, it has been entirely discredited.[54] The entry on Wythe’s life in the American National Biography, the successor to the Dictionary of American Biography, indicates that Wythe died in Richmond, "apparently poisoned by a grandnephew, George Wythe Sweeney, who lived with him and was to have been his principal heir."[55] Although this reference is tempered slightly by the use of the word "apparently," it is less tentative than the earlier dictionary entry. It does not offer any other explanation for Wythe’s death, nor any other motive for the poisoning. Other modern accounts of Wythe’s death treat it straightforwardly as a murder.[56]

Wythe as Michael Brown's father

The suggestion that Michael Brown was Wythe’s son with Lydia Broadnax, however, although also discredited, is more pervasive even in contemporary books and articles.[57] In The Wolf by the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery, John Chester Miller includes Wythe in a list of Jefferson’s slave owner friends, whom he continued to admire despite their involvement in a "corruptive" practice.[58] Wythe is singled out, however, as one who "resisted the temptation to which slave owners were exposed, [but nevertheless] succumbed to the sexual attractions of a slave woman."[59] The slave woman is almost certainly Lydia Broadnax, although Miller does not mention her by name. He does not cite any source for the allegation of a sexual relationship between her and Wythe.

Another uncited reference to Wythe’s secret family appears fleetingly in a footnote in American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, by Joseph J. Ellis. While describing Jefferson’s habit of not discussing unpleasant truths, Ellis refers to the "scandal" surrounding Wythe’s death, including "the not-to-be-mentioned fact that [Wythe’s] mulatto housekeeper was his mistress and mother of two of his children."[60] Again, one must assume that Ellis is referring to Broadnax and Brown, although it is not at all clear who the other alleged child might be.

In Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, Annette Gordon-Reed again references these rumors, although slightly more tentatively, by claiming that Wythe "was said to have had a son by a black mistress."[61] This may only be an acknowledgement that unsubstantiated rumors existed, but it does not take into account that those rumors originated with Dr. Dove 50 years after Wythe’s death. In a footnote, Gordon-Reed quotes from the beginning of the Dove Memo, using it as support that there had been talk linking Wythe to his black housekeeper and claiming that the two had a son together.[62] She does not put the Memo into context but quotes it as a primary source alongside the opinions of twentieth century Wythe biographers and historians.

Mechal Sobel, in The World They Made Together: Black and White Values in Eighteenth Century Virginia, implies, without explicitly stating, that Wythe was Brown’s father.[63] Her brief paragraph on Brown’s upbringing is placed within a larger discussion of interracial sexual and romantic relationships and miscegenation of the time, and while she never links Broadnax directly to Brown as mother and son, she does state that Broadnax was "the woman responsible for his upbringing."[64] Notably, Sobel does not mention Wythe’s murder in the text itself, but emphasizes that Brown was "poisoned by Wythe’s white nephew, apparently jealous of Brown’s status as heir to Wythe’s estate and perhaps ashamed of his public position."[65] Sobel does not cite the Dove Memo directly, but her proposed motive for the Wythe and Michael Brown murders is the same as that given by Dr. Dove: that Sweeney was jealous of Brown’s status and "public position."

In his biography of Wythe, Jefferson’s Second Father, John Bailey gives particular credit to the Dove Memo as lending "historical authority" to a "longstanding folklore" claim that Michael Brown was Wythe’s son.[66] Bailey, however, also claims that Dr. Dove wrote the memo "in his own hand," at the end of his life, while living in California.[67] According to the Memo itself, the information it contains was recounted by Dove, but written down by Thomas Hicks Wynne. Dove seems to have spent his entire life in Richmond, Virginia, where he died in 1872, over 15 years after the Memo was written.[68] In addition to the Memo, Bailey cites George Wythe Munford’s statement that Broadnax was "respected and trusted by her master, and devotedly attached to him," as proof that Broadnax was Wythe’s mistress.[69] He cites the content of Wythe’s will, which provided for Broadnax, Brown, and a third freed slave, Ben, and which Bailey argues must have seemed like "proof that Wythe was anxious to provide Broadnax and Ben with the income to raise his son in an advantageous manner," as proof that Michael was Wythe’s son.[70]

In a blog post about the events surrounding Wythe’s death, “The Curious Death of George Wythe: ‘I Am Murdered!’”, Mark Esposito makes three uncritical references to Michael Brown as Broadnax’s son.[71] He also addresses the possibility that Wythe might be Brown’s father, giving the idea some credence despite admitting that "there is scant evidence to support that conclusion."[72] By emphasizing that Wythe "provided Brown a remarkable education at a time when such an advantage was generally denied to persons of color," that he "even went so far as" putting Thomas Jefferson in charge of Brown’s education after Wythe’s death, and that "it is ... without contradiction that Wythe made generous bequests to Broadnax and Brown," Esposito subtly implies that Wythe was closer to Broadnax and Brown than he would ever be to a housekeeper or ward.[73] As late as 2010, a rumor that originated with Dr. Dove 50 years after Wythe’s death was being repeated, if less directly and explicitly, in relation to his death.

There are several potential reasons why the story of Wythe’s alleged interracial affair has remained so popular. First, it is a sensational story, and makes an interesting narrative even if it is not at all based in fact. Second, several of the authors who reference the story favorably are not writing on Wythe specifically, and may have found that the Wythe/Lydia Broadnax/Michael Brown story, even if supported by weak circumstantial evidence and an untrustworthy primary source, simply fit well with the larger historical narrative they were telling.

Third, the story that Michael Brown was Wythe’s son provides a convenient explanation not only for why Wythe was educating and providing for Brown, but for how Brown came to the Wythe household at all. His origins are otherwise unknown. It does not seem likely that he was one of Wythe’s former slaves, and "Brown" was a common last name for free black people in Richmond at the time. Morgan suggests that Wythe’s friend William DuVal might have been involved in bringing Brown to the Wythe home, because DuVal freed about twenty of his own slaves and some of them took the last name Brown, but this is merely speculative.[74]

Finally, several of the writers who give credence to the story that Brown was or could have been Wythe’s son, including Gordon-Reed, Sobel, and Esposito, specifically cite historian Fawn Brodie’s 1974 Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History. In this well-known book, Brodie claims not only that Wythe fathered Brown, but that Brown’s parentage was commonly accepted knowledge in Richmond at the time of Wythe’s death.[75] Although Brodie did not specifically cite to the Dove Memo, Kirtland believes that she "clearly base[d] her statements on an uncritical use of this source."[76] It is the "only ... document [that] exists that in any way lends credence to [her] allegations."[77] Her analysis and conclusion have since been thoroughly refuted,[78] but clearly had a broad influence.

Sweeney's life after his acquittal

Little is known of Sweeney’s life after he was cleared of any guilt in the deaths of George Wythe and Michael Brown. The only sources that describe his movements after 1806 are Minor’s "Memoir of the Author" and the Dove Memo itself, both written half a century after Sweeney’s trial.

According to Minor, Sweeney "sought refuge in the West; where his career was brought to a premature and miserable close."[79] Minor may have gotten this information from Dove: it appears on the same page as his footnote recounting Dove’s version of the events surrounding Wythe’s death, and though not specifically attributed to him, is given no other attribution.

The last lines of the Dove Memo report that, after his acquittal, Sweeney "went to Tennessee stole a horse and was sent to the penitentiary and then lost sight of." This story is compatible with, and only slightly more detailed than, the one appearing in Minor. Originating as it does with the generally untrustworthy Dr. Dove, this account of Sweeney’s later life cannot be given too much credence. It "must be considered traditionary rather than supported by valid evidence."[80] Attempts either to find additional documentary evidence of Sweeney’s incarceration in Tennessee, or to trace his movements from Tennessee, have been unsuccessful.[81] Nevertheless, probably because the Memo is the only source of information that we do have on Sweeney’s life in the aftermath of the trial, the story of Sweeney’s incarceration in Tennessee is often repeated in contemporary accounts of the events.[82]

See also

- Death of George Wythe

- George Wythe Sweeney

- Hustings Court Minutes

- Hustings Court Order Book

- Richmond Enquirer, 9 September 1806

- Virginia Argus, 10 September 1806

- Virginia Argus, 25 June 1806

References

- ↑ Although it should more properly be a singular "Memorandum," cited here as written by Wynne: "Memoranda Concerning the Death of Chancellor Wythe: Signed in the Aut[o]g[rap]h. of T[homas] H. Wynne and Rec[eive]d by Him from Dr. John Dove, Sept. 16, 1856." MS. in Thomas Wynne Hicks Correspondence and Documents, 1848-1860, folder 4, Box 133, Brock Collection, Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

- ↑ "Death of Dr. John Dove," Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 17, 1872, quoted in Freemasons, Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of the Most Ancient and Honorable Fraternity of Accepted Masons of the Common Wealth of Massachusetts (Boston: Press of Rockwell & Churchill, 1876), 152.

- ↑ Wyndham B. Blanton, Medicine in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century (Richmond: Garrett & Massie, incorporated, 1933): 48, 76, 91, 238, 240, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001557340.

- ↑ Ibid., 238, 48.

- ↑ "Death of Dr. John Dove," quoted in Freemasons, Proceedings of the Grand Lodge, 152.

- ↑ Freemasons, Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, "Report of Committee on the Death of R.W. John Dove, M.D.," in Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of the Most Ancient and Honorable Fraternity of Accepted Masons (Boston: Press of Rockwell & Churchill, 1876), 51.

- ↑ Ibid., 151.

- ↑ B.B. Minor, "Memoir of the Author," in Decisions of Cases in Virginia, By the High Court Chancery, with Remarks Upon Decrees By the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, by George Wythe, ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond, Virginia: J.W. Randolph, 1852), xxviii.

- ↑ Julian P. Boyd, "The Murder of George Wythe," in The Murder of George Wythe: Two Essays, Julian P. Boyd and W. Edwin Hemphill (Williamsburg, VA: The Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1955), 27.

- ↑ Robert Bevier Kirtland, "George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1983), 163n12.

- ↑ Philip D. Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake and the British Atlantic World, c. 1700-1820," in Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, and Civic Culture, ed. Jan Ellen Lewis and Peter. S. Onuf (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), 57; "Death of Dr. John Dove," quoted in Freemasons, Proceedings of the Grand Lodge, 152.

- ↑ Kirtland, "George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge," 162-63.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 57.

- ↑ Boyd, "The Murder of George Wythe," 29-30.

- ↑ Ibid., 30.

- ↑ Ibid., 27.

- ↑ Ibid., 30.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Imogene Brown, "Appendix: The Brodie Allegations," in American Aristides (East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Press, 1981): 305n23.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Boyd, "The Murder of George Wythe," 27.

- ↑ W. Edwin Hemphill, "Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder: A Documentary Essay," in The Murder of George Wythe: Two Essays, Julian P. Boyd and W. Edwin Hemphill (Williamsburg, VA: The Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1955), 39n21.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Brown, "The Brodie Allegations," 298.

- ↑ Boyd, "The Murder of George Wythe," 27.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 57.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Brown, "The Brodie Allegations," 299.

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 57.

- ↑ Ibid. (Morgan also points out that Wythe was 65 when Michael was born, 58); Brown, "The Brodie Allegations," 299.

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 57; Brown "The Brodie Allegations," 299.

- ↑ Brown, "The Brodie Allegations," 299.

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 58.

- ↑ Brown, "The Brodie Allegations," 301.

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 58.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Brown, "The Brodie Allegations," 300.

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 58.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 305n23.

- ↑ Boyd, “The Murder of George Wythe,” 24-25.

- ↑ Lyon G. Taylor, "George Wythe," in Great American Lawyers: The Lives and Influence of Judges and lawyers who have Acquired Permanent National Reputation, and have Developed the Jurisprudence of the United States. A History of the Legal Profession, ed. William Draper Lewis (Philadelphia: The J.C. Winston Company, 1907), 84.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, s.v. "Wythe, George," quoted in Boyd, "The Murder of George Wythe," 24-25 Boyd traces the story of an accidental poisoning, not to the Dove Memo itself, but to the less detailed version of Dr. Dove’s story found in Minor’s footnote in "Memoir of the Author."

- ↑ Boyd, "The Murder of George Wythe," 25.

- ↑ Hemphill, "Examinations of George Wythe Swinney," 38.

- ↑ See Boyd, "The Murder of George Wythe," 25-31 (discrediting the accidental death theory by comparison with more contemporary sources) and Hemphill, "Examination of George Wythe Swinney" (transcribing and analyzing court documents from Sweeney’s grand jury trial, which make no distinction between a plan to murder Michael Brown and a plan to murder Wythe).

- ↑ Robert Kirtland, "Wythe, George," in American National Biography Online, accessed November 19, 2014.

- ↑ See, e.g., Bruce Chadwick, I Am Murdered: George Wythe, Thomas Jefferson, and the Killing That Shocked a New Nation (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2009); Mary Miley Theobald, "Murder by Namesake: The Poisoning of the Eminent George Wythe," Colonial Williamsburg 35 (Winter 2013); Mark Esposito, "The Curious Death of George Wythe: “I Am Murdered!", Jonathan Turley (blog), December 12, 2010, .

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 79n8 (listing historians who have repeated the story of the alleged family ties among Wythe, Lydia, and Michael, discussed below).

- ↑ John Chester Miller, The Wolf by the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1977): 42-43.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Joseph J. Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997): 327n32.

- ↑ Annette Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1997): 136.

- ↑ Ibid., 267n43.

- ↑ Mechal Sobel, The World They Made Together: Black and White Values in Eighteenth-Century Virginia (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987): 152.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ John Bailey, Jefferson’s Second Father (Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia, 2013): 239.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Freemasons, "Report of Committee," in Proceedings of the Grand Lodge, 151.

- ↑ Bailey, Jefferson’s Second Father, 239-40.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Esposito, "The Curious Death of George Wythe," paras. 1-3.

- ↑ Ibid., para. 5.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake," 59.

- ↑ Fawn Brodie, Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1974): 390-91.

- ↑ Kirtland, "George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary, Judge," 163n12.

- ↑ Brown, “The Brodie Allegations,” 305n23.

- ↑ E.g., Ibid., 298-305.

- ↑ Minor, "Memoir of the Author," xxviii.

- ↑ Hemphill, "Examinations of George Wythe Swinney," 63.

- ↑ Chadwick, I Am Murdered, 238-39. Because "Tennessee did not inaugurate a state-wide prison system until the 1820s," there are no records of Sweeney’s alleged incarceration there.

- ↑ E.g., Ibid.; Esposito, “The Curious Death of George Wythe,” para. 17, http://allthingsliberty.com/2013/12/murder-declaration-signer-part-2/; Daniel P. Berexa, "The Murder of Founding Father George Wythe," Tennessee Bar Journal 47 (Jan. 2011); John L. Smith, "Murder of a Declaration Signer (Part 2)," Journal of the American Revolution, December 5, 2013, para. 17.