Difference between revisions of "Kainē Diathēkē"

m |

m |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}}The second part of the Christian biblical canon, the [[wikipedia: New Testament| New Testament]] consists of several texts originally written in [[wikipedia: Koine Greek| Koine Greek]]. Historians do not know when the first compilation of the New Testament occurred, nor do they know who compiled it.<ref>Bruce M. Metzger "History of Editing the Greek New Testament," ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 131, no. 2 (1987): 148.</ref> The [[wikipedia:Complutensian_Polyglot_Bible|Complutensian Polyglot Bible]] edited by [[wikipedia:Francisco_Jiménez_de_Cisneros|Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros]] (1436-1517) included the first printed Greek New Testament (1514) but the 1516 edition by [[wikipedia:Erasmus|Desiderius Erasmus]] preceded the delayed publication of the Polyglot Bible by four years.<ref>Ibid, 70.</ref><ref>D. Parker, "[https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601180.001.0001/acref-9780198601180-chapter-6 The New Testament]," in ''The Oxford Illustrated History of the Bible'', accessed March 31, 2023.</ref> Unfortunately, Erasmus used a limited number of relatively recent, incomplete Greek texts and translated back from the Latin [[wikipedia:Vulgate|Vulgate]] when lacking the material he needed. The result has been dubbed "the most inaccurate book ever printed."<ref>Ibid.</ref> It influenced all subsequent versions of the New Testament printed until the nineteenth century.<ref>Charles B. Puskas and C. Michael Robbins, ''An Introduction to the New Testament'' (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2011): 70.</ref> | }}The second part of the Christian biblical canon, the [[wikipedia: New Testament| New Testament]] consists of several texts originally written in [[wikipedia: Koine Greek| Koine Greek]]. Historians do not know when the first compilation of the New Testament occurred, nor do they know who compiled it.<ref>Bruce M. Metzger "History of Editing the Greek New Testament," ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 131, no. 2 (1987): 148.</ref> The [[wikipedia:Complutensian_Polyglot_Bible|Complutensian Polyglot Bible]] edited by [[wikipedia:Francisco_Jiménez_de_Cisneros|Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros]] (1436-1517) included the first printed Greek New Testament (1514) but the 1516 edition by [[wikipedia:Erasmus|Desiderius Erasmus]] preceded the delayed publication of the Polyglot Bible by four years.<ref>Ibid, 70.</ref><ref>D. Parker, "[https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601180.001.0001/acref-9780198601180-chapter-6 The New Testament]," in ''The Oxford Illustrated History of the Bible'', accessed March 31, 2023.</ref> Unfortunately, Erasmus used a limited number of relatively recent, incomplete Greek texts and translated back from the Latin [[wikipedia:Vulgate|Vulgate]] when lacking the material he needed. The result has been dubbed "the most inaccurate book ever printed."<ref>Ibid.</ref> It influenced all subsequent versions of the New Testament printed until the nineteenth century.<ref>Charles B. Puskas and C. Michael Robbins, ''An Introduction to the New Testament'' (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2011): 70.</ref> | ||

| − | ''Hē Kainē Diathēkē'', printed in London in 1743, follows in the line of Greek New Testaments derived from the editions of Erasmus and specifically falls in the sub-family of "Editio Millii." So dubbed by Eduard Reuss in his 1872 book ''Bibliotheca Novi Testamenti Graeci'',<ref>Eduard Reuss, ''Bibliotheca Novi Testamenti Graeci'' (Brunswick: Apud C. A. Sshwetschke et Filium, 1872): 138, 140.</ref> these editions emanate from the work of [[wikipedia: John_Mill_(theologian)|John Mill]] (1645-1707). Published weeks before his death, Mill's edition incorporated 30 years of research collating different manuscripts and fragments of the Greek New Testament.<ref>D. Parker, "The New Testament."</ref> Mill printed an edition of the textus receptus (received text)<ref>Ibid. A text published by Dutch printers [[wikipedia:House_of_Elzevir|Bonaventure and Abraham Elzevir]] in Leiden in 1633 which "claim[ed] in its preface to be the ‘text received by all’, the textus receptus." This was the general text most commonly used for the next several centuries.</ref> with a listing below the text of all the variants reviewed | + | ''Hē Kainē Diathēkē'', printed in London in 1743, follows in the line of Greek New Testaments derived from the editions of Erasmus and specifically falls in the sub-family of "Editio Millii." So dubbed by Eduard Reuss in his 1872 book ''Bibliotheca Novi Testamenti Graeci'',<ref>Eduard Reuss, ''Bibliotheca Novi Testamenti Graeci'' (Brunswick: Apud C. A. Sshwetschke et Filium, 1872): 138, 140.</ref> these editions emanate from the work of [[wikipedia: John_Mill_(theologian)|John Mill]] (1645-1707). Published weeks before his death, Mill's edition incorporated 30 years of research collating different manuscripts and fragments of the Greek New Testament.<ref>D. Parker, "The New Testament."</ref> Mill printed an edition of the textus receptus (received text)<ref>Ibid. A text published by Dutch printers [[wikipedia:House_of_Elzevir|Bonaventure and Abraham Elzevir]] in Leiden in 1633 which "claim[ed] in its preface to be the ‘text received by all’, the textus receptus." This was the general text most commonly used for the next several centuries.</ref> with a listing below the text of all the variants he had reviewed.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Some of the manuscripts Mill consulted predated the ones used in creating the received text and thus cast doubt upon its accuracy.<ref>Ibid.</ref> This 1743 version was the third edition published in London by William Bowyer following Mill's original 1707 Oxford publication. |

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 14:36, 3 April 2023

| He Kaine Diatheke. Novum Testamentum | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Published | Londini: Excudebat G. Bowyer, Impensis Societatis Stationariorum | |

| Date | 1743 | |

The second part of the Christian biblical canon, the New Testament consists of several texts originally written in Koine Greek. Historians do not know when the first compilation of the New Testament occurred, nor do they know who compiled it.[1] The Complutensian Polyglot Bible edited by Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros (1436-1517) included the first printed Greek New Testament (1514) but the 1516 edition by Desiderius Erasmus preceded the delayed publication of the Polyglot Bible by four years.[2][3] Unfortunately, Erasmus used a limited number of relatively recent, incomplete Greek texts and translated back from the Latin Vulgate when lacking the material he needed. The result has been dubbed "the most inaccurate book ever printed."[4] It influenced all subsequent versions of the New Testament printed until the nineteenth century.[5]

Hē Kainē Diathēkē, printed in London in 1743, follows in the line of Greek New Testaments derived from the editions of Erasmus and specifically falls in the sub-family of "Editio Millii." So dubbed by Eduard Reuss in his 1872 book Bibliotheca Novi Testamenti Graeci,[6] these editions emanate from the work of John Mill (1645-1707). Published weeks before his death, Mill's edition incorporated 30 years of research collating different manuscripts and fragments of the Greek New Testament.[7] Mill printed an edition of the textus receptus (received text)[8] with a listing below the text of all the variants he had reviewed.[9] Some of the manuscripts Mill consulted predated the ones used in creating the received text and thus cast doubt upon its accuracy.[10] This 1743 version was the third edition published in London by William Bowyer following Mill's original 1707 Oxford publication.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

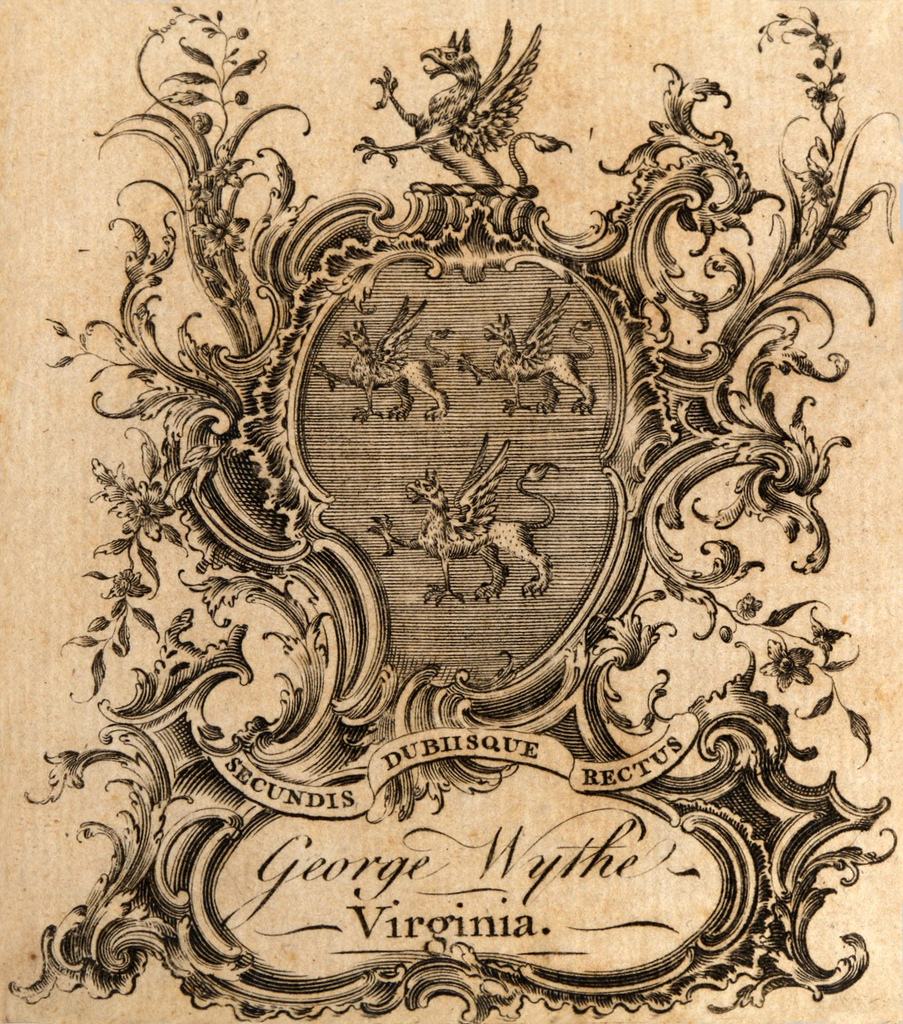

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Novum testamentum. Gr. 12mo. Lond. 1743. Bower" This was one of the titles kept by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson may have sold it the Library of Congress in 1815. Both George Wythe's Library[11] on LibraryThing and the Brown Bibliography[12] list the 1743 edition published in London based on the Jefferson copy at the Library of Congress.[13] While the copy still exists, both George Wythe's Library[14] on LibraryThing and the Brown Bibliography[15] note the copy was rebound for Jefferson with his shelfmark. As such, any possible ties to Wythe would have been removed. As of yet, the Wolf Law Library has been unable to procure a copy of Kainē Diathēkē.

See also

- George Wythe Room

- The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments

- Jefferson Inventory

- Tes Kaines Diathekes Apanta = Novum Testamentum

- Tēs Kainēs Diathēkēs Hapanta = Novum Testamentum

- Hē Palaia Diatheke Kata tous Hebdomenkonta = Vetus Testamentum Græcum

- Psaltērion Psalterium

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ Bruce M. Metzger "History of Editing the Greek New Testament," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 131, no. 2 (1987): 148.

- ↑ Ibid, 70.

- ↑ D. Parker, "The New Testament," in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Bible, accessed March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Charles B. Puskas and C. Michael Robbins, An Introduction to the New Testament (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2011): 70.

- ↑ Eduard Reuss, Bibliotheca Novi Testamenti Graeci (Brunswick: Apud C. A. Sshwetschke et Filium, 1872): 138, 140.

- ↑ D. Parker, "The New Testament."

- ↑ Ibid. A text published by Dutch printers Bonaventure and Abraham Elzevir in Leiden in 1633 which "claim[ed] in its preface to be the ‘text received by all’, the textus receptus." This was the general text most commonly used for the next several centuries.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe", accessed on February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 2:99-100 [no.1480].

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe", accessed on February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433