Difference between revisions of "Adagiorum D. Erasmi Roterodami Epitome"

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desiderius_Erasmus Desiderius Erasmus] (c. 1467-1536) was a scholar, writer, and humanist who contributed valuable religious translations and writings to sixteenth century thinkers. Erasmus studied at a number of schools throughout his life, including those at the church of St. John of Gouda, St. Lebuin in Deventer, Hertogenbosch, Cambridge, as well as schools in Paris. The scholar joined the Roman Catholic Church as a monk near the age of twenty. Erasmus continually traveled, studied, and wrote during his monastic years, gaining notice for his translation of the New Testament and opposition to Martin Luther.<ref>James McConica, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/39358 “Erasmus, Desiderius”] in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed Sept. 30, 2013.</ref> Erasmus, similar to Luther, spoke out regarding the failings of the church and encouraged reform. Erasmus particularly deplored the “religious warfare” of the time and the cultural decline it produced within the church.<ref>“Erasmus” in ''Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia'', 6th Edition (Columbia University Press, 2013- ), accessed Sept. 27, 2013.</ref> During the Reformation period, both the Protestants and Roman Catholics used Erasmus’ writings in support or disapproval of church doctrine. Erasmus never sided with either religious group, but was very influential on both sides.<ref>Robert M. Thorton, “Erasmus,” ''Modern Age'' 47, no. 4, (2005): 367.</ref> Erasmus remained a part of the Roman Catholic Church until his death.<br /> | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desiderius_Erasmus Desiderius Erasmus] (c. 1467-1536) was a scholar, writer, and humanist who contributed valuable religious translations and writings to sixteenth century thinkers. Erasmus studied at a number of schools throughout his life, including those at the church of St. John of Gouda, St. Lebuin in Deventer, Hertogenbosch, Cambridge, as well as schools in Paris. The scholar joined the Roman Catholic Church as a monk near the age of twenty. Erasmus continually traveled, studied, and wrote during his monastic years, gaining notice for his translation of the New Testament and opposition to Martin Luther.<ref>James McConica, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/39358 “Erasmus, Desiderius”] in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed Sept. 30, 2013.</ref> Erasmus, similar to Luther, spoke out regarding the failings of the church and encouraged reform. Erasmus particularly deplored the “religious warfare” of the time and the cultural decline it produced within the church.<ref>“Erasmus” in ''Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia'', 6th Edition (Columbia University Press, 2013- ), accessed Sept. 27, 2013.</ref> During the Reformation period, both the Protestants and Roman Catholics used Erasmus’ writings in support or disapproval of church doctrine. Erasmus never sided with either religious group, but was very influential on both sides.<ref>Robert M. Thorton, “Erasmus,” ''Modern Age'' 47, no. 4, (2005): 367.</ref> Erasmus remained a part of the Roman Catholic Church until his death.<br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | Erasmus collected Greek adages and first published them in 1500 as ''Adagiorum Collectanea''. This short work of 818 adages formed the basis for ''Adagiorum Chiliades'', first published in 1508 with 3,260 adages. Successive editions continued to embellish the work. The edition published in 1536, the year of Erasmus' death, included 4,151 adages.<ref>James McConica, “Erasmus, Desiderius.”</ref> One editor praised the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adagia '' | + | Erasmus collected Greek adages and first published them in 1500 as ''Adagiorum Collectanea''. This short work of 818 adages formed the basis for ''Adagiorum Chiliades'', first published in 1508 with 3,260 adages. Successive editions continued to embellish the work. The edition published in 1536, the year of Erasmus' death, included 4,151 adages.<ref>James McConica, “Erasmus, Desiderius.”</ref> One editor praised the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adagia ''Adages''] as "an extraordinary work of Renaissance erudition" explaining that "Erasmus gathers Greek and Latin sources for thousands of proverbs such as 'To have one foot in the grave', 'To be in the same boat', or 'To put the cart before the horse.'"<ref>Desiderius Erasmus, ''The Agages of Erasmus,'' ed. William Barker (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), [ix].</ref> The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries witnessed the publication of a "range of epitomes",<ref>Erasmus, ''The Adages of Erasmus'', xxii.</ref> or abridged versions, such as ''Adagiorum D. Erasmi Roterodami Epitome''. In these, thousands of entries were either shortened or removed altogether. The concise editions, evidently approved by Erasmus, were intended as "quick guides to usage."<ref>Ibid.</ref> |

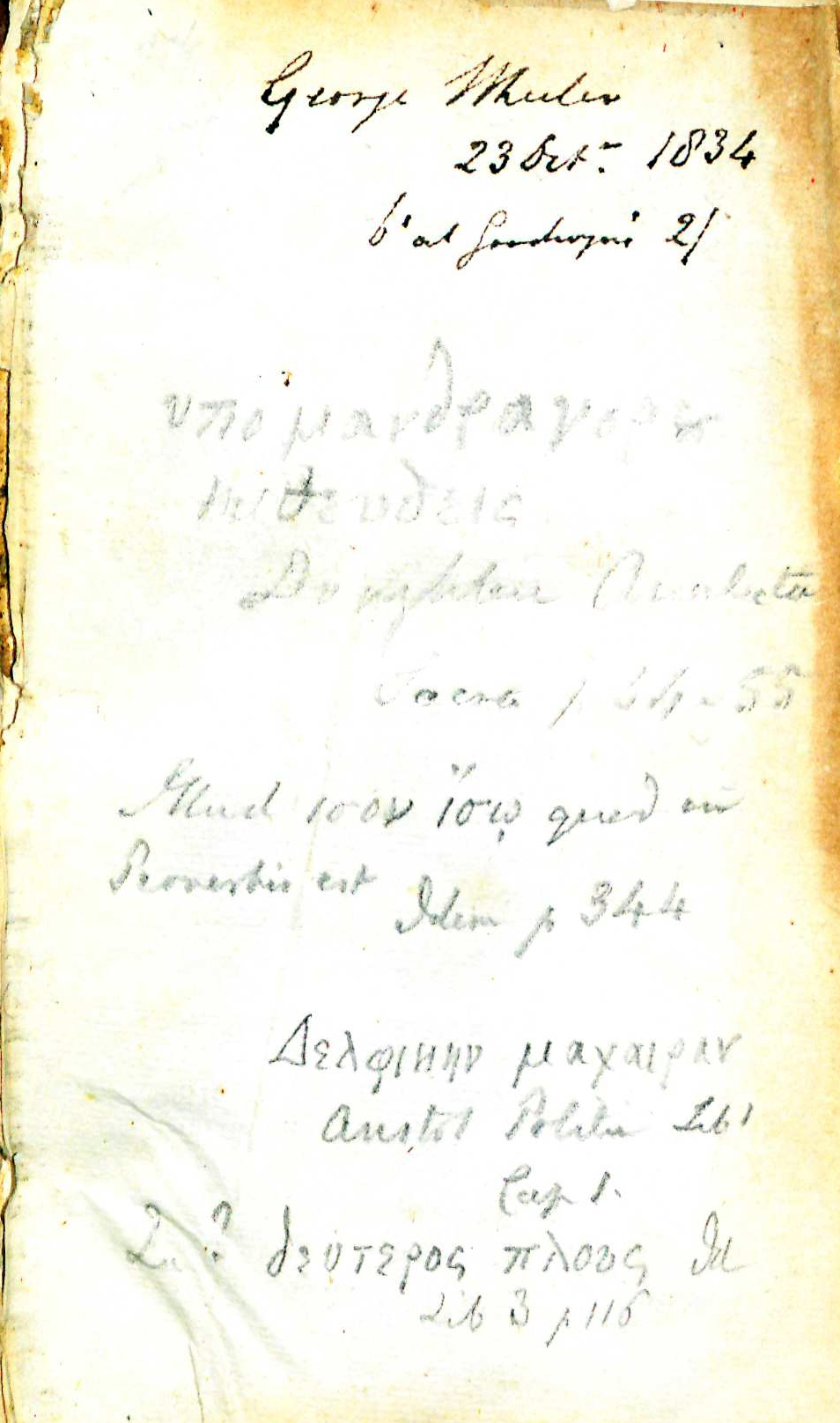

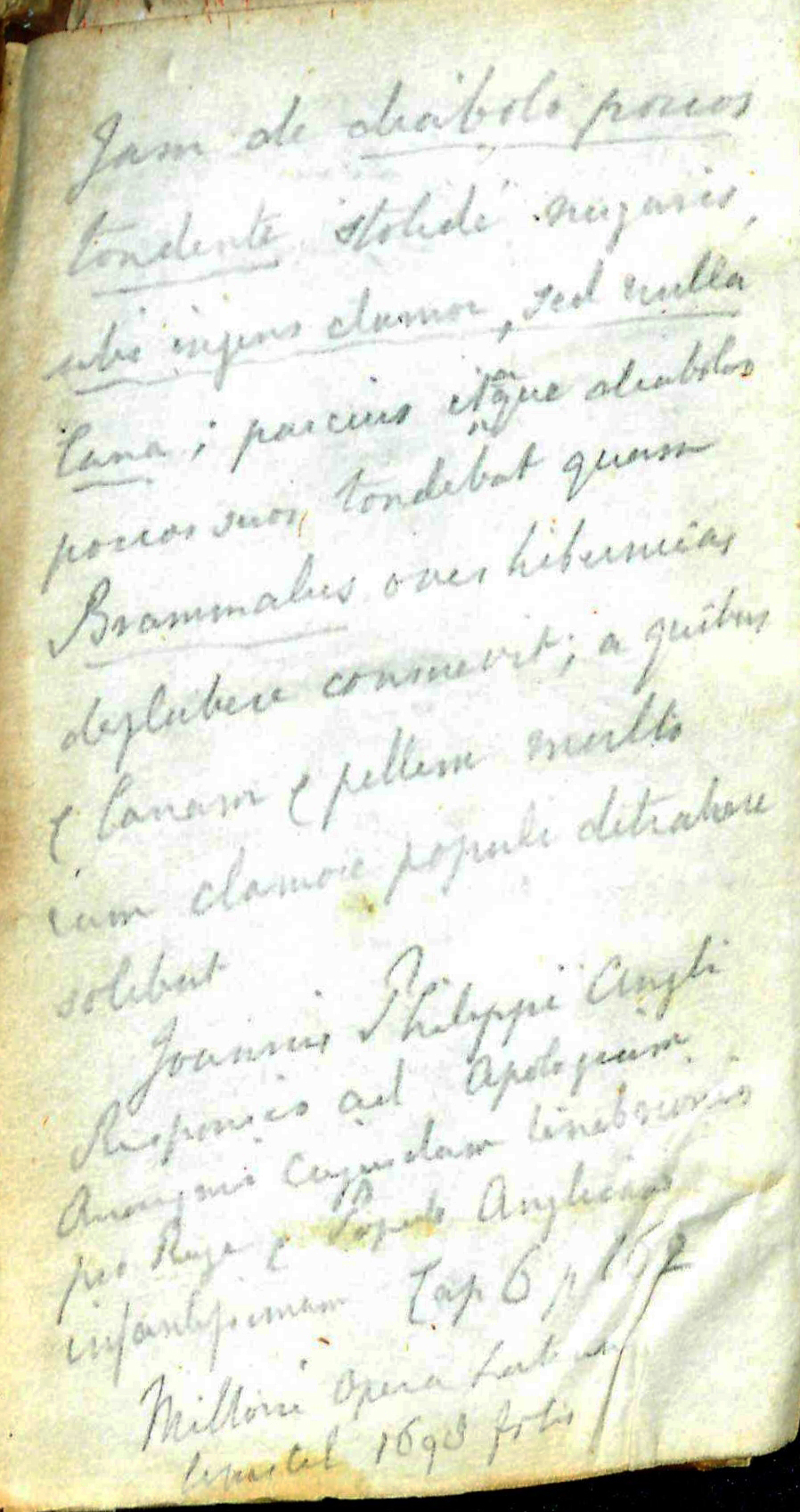

[[File:ErasmusAdagiorum1663Inscriptions.jpg|left|thumb|200px|<center>Inscriptions, front free endpaper.</center>]] | [[File:ErasmusAdagiorum1663Inscriptions.jpg|left|thumb|200px|<center>Inscriptions, front free endpaper.</center>]] | ||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 15:18, 31 March 2014

by Desiderius Erasmus

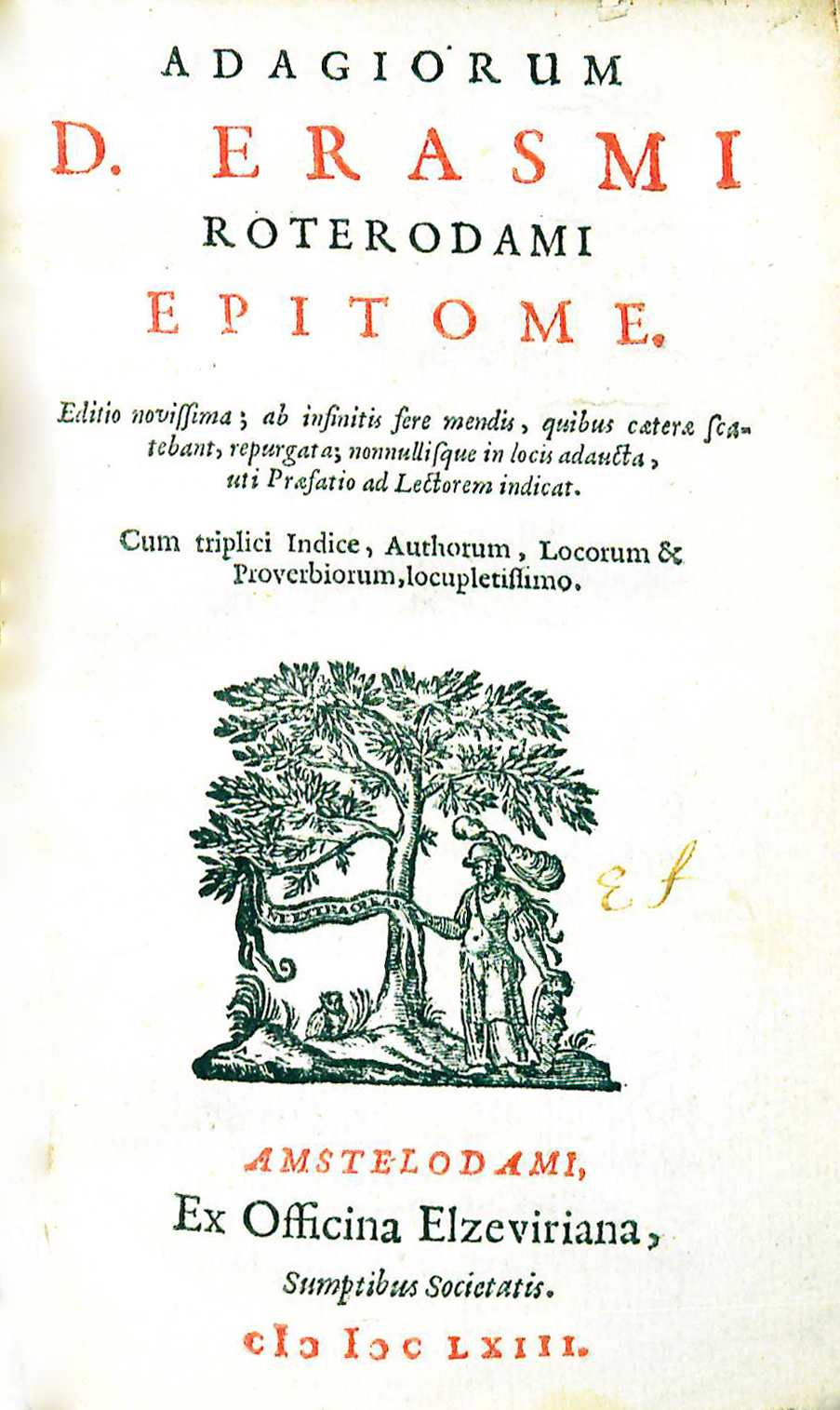

| Adagiorum D. Erasmi Roterodami Epitome | |

|

Title page from Adagiorum D. Erasmi Roterodami Epitome, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Desiderius Erasmus |

| Published | Amstelodami: Ex officina Elzeviriana, Sumptibus Societatis |

| Date | 1663 |

| Language | Latin |

| Pages | [24], 622, [72] |

| Desc. | 12 mo (14 cm.) |

Desiderius Erasmus (c. 1467-1536) was a scholar, writer, and humanist who contributed valuable religious translations and writings to sixteenth century thinkers. Erasmus studied at a number of schools throughout his life, including those at the church of St. John of Gouda, St. Lebuin in Deventer, Hertogenbosch, Cambridge, as well as schools in Paris. The scholar joined the Roman Catholic Church as a monk near the age of twenty. Erasmus continually traveled, studied, and wrote during his monastic years, gaining notice for his translation of the New Testament and opposition to Martin Luther.[1] Erasmus, similar to Luther, spoke out regarding the failings of the church and encouraged reform. Erasmus particularly deplored the “religious warfare” of the time and the cultural decline it produced within the church.[2] During the Reformation period, both the Protestants and Roman Catholics used Erasmus’ writings in support or disapproval of church doctrine. Erasmus never sided with either religious group, but was very influential on both sides.[3] Erasmus remained a part of the Roman Catholic Church until his death.

Erasmus collected Greek adages and first published them in 1500 as Adagiorum Collectanea. This short work of 818 adages formed the basis for Adagiorum Chiliades, first published in 1508 with 3,260 adages. Successive editions continued to embellish the work. The edition published in 1536, the year of Erasmus' death, included 4,151 adages.[4] One editor praised the Adages as "an extraordinary work of Renaissance erudition" explaining that "Erasmus gathers Greek and Latin sources for thousands of proverbs such as 'To have one foot in the grave', 'To be in the same boat', or 'To put the cart before the horse.'"[5] The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries witnessed the publication of a "range of epitomes",[6] or abridged versions, such as Adagiorum D. Erasmi Roterodami Epitome. In these, thousands of entries were either shortened or removed altogether. The concise editions, evidently approved by Erasmus, were intended as "quick guides to usage."[7]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Wythe ordered "Erasmus's adages" from John Norton & Sons in a [[Wythe to John Norton, 29 May 1772|letter] dated May 29, 1772. Records indicate the order was fulfilled.[8] "Erasmi Adagiorum epitome. p. f." is also listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library. This was one of the titles kept by Thomas Jefferson. He sold a copy of the 1663 edition of Adagiorum D. Erasmi Roterdami Epitome to the Library of Congress in 1815 and that copy still exists today. However, the volume has no definitive markings linking it to Wythe.[9] Both George Wythe's Library[10] on LibraryThing and the Brown Bibliography[11] include the 1663 edition at the Library of Congress as Wythe's copy. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the same edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in full brown calf with tooled border lines on the front and back covers. Three raised bands to the spine with tooled surround lines and red speckled pages. Includes notes of a previous owner in Greek and Latin on the front free endpaper and its verso. The signature of "George Wheeler" 23 Oct. 1834" is also on the front free endpaper. Purchased from Abe Books.

View this book in [hhttps://catalog.swem.wm.edu/law/Record/3473585 William & Mary's online catalog].

References

- ↑ James McConica, “Erasmus, Desiderius” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed Sept. 30, 2013.

- ↑ “Erasmus” in Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition (Columbia University Press, 2013- ), accessed Sept. 27, 2013.

- ↑ Robert M. Thorton, “Erasmus,” Modern Age 47, no. 4, (2005): 367.

- ↑ James McConica, “Erasmus, Desiderius.”

- ↑ Desiderius Erasmus, The Agages of Erasmus, ed. William Barker (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), [ix].

- ↑ Erasmus, The Adages of Erasmus, xxii.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Frances Norton Mason, ed., John Norton & Sons, Merchants of London and Virginia: Being the Papers from their Counting House for the Years 1750 to 1795 (Richmond, Virginia: Dietz Press, 1937), 242-243. The letter is endorsed "Virga. 29 May 1772 / George Wythe / Recd. 21 September / Goods Entr. pa. 163/ Ans. the March 1773."

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 2:52-53 [no.1363].

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe" accessed on March 5, 2014.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

External Links

Read this book in Google Books.