Hinde v. Pendleton

Hinde v. Pendleton, Wythe 354 (1791),[1] discussed whether a buyer had to pay the full price for slaves he bought at auction when the auctioneer employed a by-bidder (i.e., a shill) to inflate the price without the seller's knowledge, and when the seller knew that the buyer had a strong personal attachment to the slaves.

Background

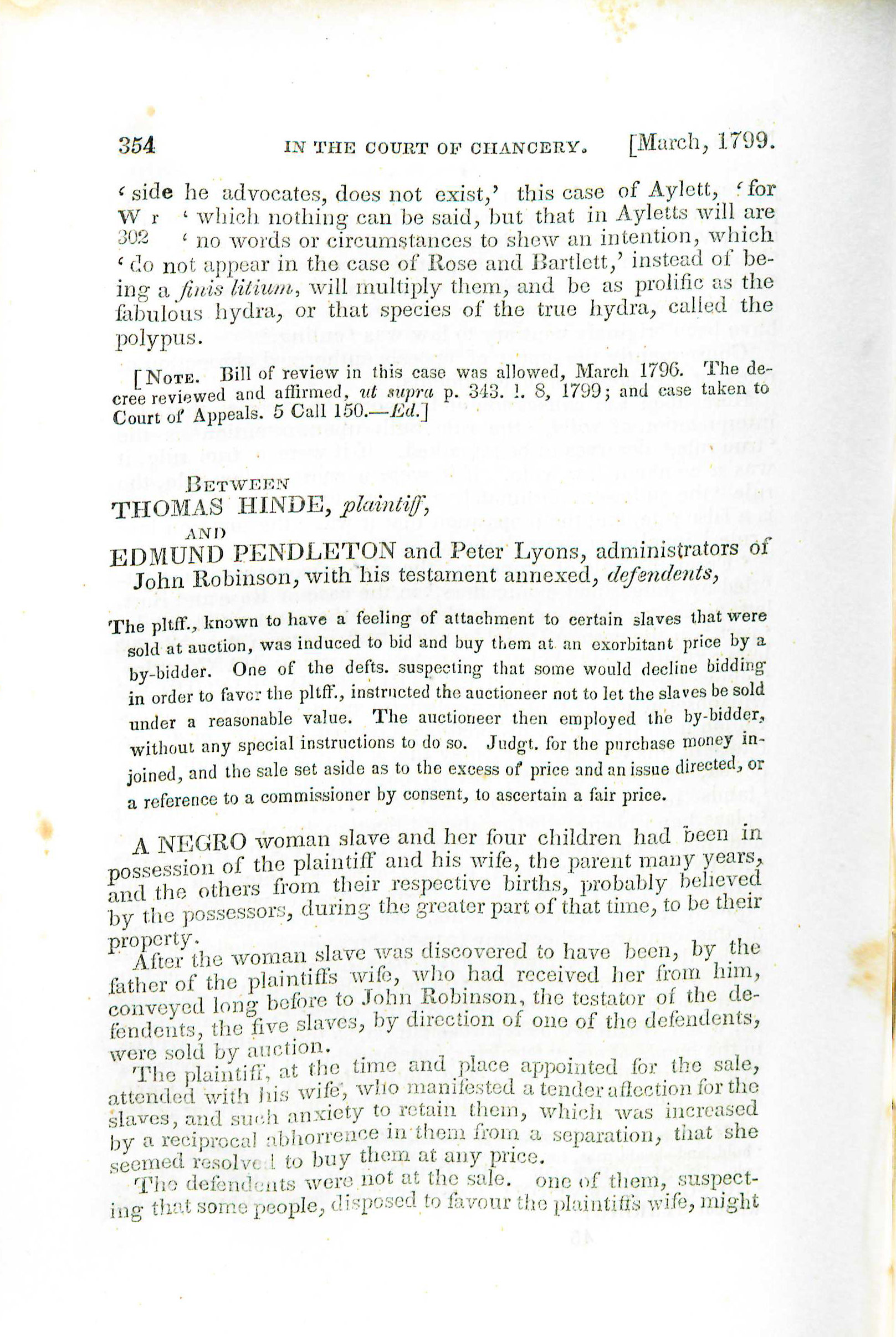

Thomas Hinde possessed a female slave and her four children for many years under the assumption that he owned them. One day, though, Hinde's father-in-law, who had originally given Hinde the female slave before her children were born, revealed that he had previously given title in the slaves to John Robinson. Wythe does not say exactly when this happened, but from context it seems as if Hinde's father-in-law gave the title to Robinson before Hinde's marriage. By the time Hinde's father-in-law revealed this information, Robinson was dead, so the defendants in this case were Edmund Pendleton and Peter Lyons, the executors of Robinson's estate.

Either Pendleton or Lyons (Wythe does not say who) directed that the five slaves be sold at an auction, which Hinde and his wife attended. According to Wythe, Hinde's wife expressed "tender affection for the slaves",[2] and the slaves expressed a desire not to be separated from the Hindes, so Hinde's wife was determined to buy the slaves at any cost.

Neither Pendleton nor Lyons were at the auction, but one of them (again, Wythe does not say who) told the auctioneer not to sell the slaves below a "reasonable price" because he feared the other bidders would defer to Hinde's wife and refuse to compete with her. Unknown to the defendants, the auctioneer employed a shill to inflate the final selling price, and the slaves ultimately sold for 52,000 pounds of tobacco, which was "confessed to be (an) enormous (price)".[3] Hinde signed a bond with a surety (i.e., a co-signer) to guarantee the purchase price.

Pendleton and Lyons filed suit in another court and won a judgment to collect the 52,000 pounds of tobacco.

Hinde filed a bill with the High Court of Chancery to enjoin Pendleton and Lyons from carrying out the other court's judgment. Hinde claimed that he owned the slaves all along because his father-in-law made them a wedding gift to Hinde. In addition, the auctioneer's use of a shill was so unfair that under equity Hinde should only have to pay the market value of the slaves. Pendleton and Lyons replied that when Hinde's father-in-law delivered title in the slaves to Robinson, that pre-empted any title Hinde may have gotten from his father-in-law's gift later on. Pendleton added, in what Wythe described as a "dissertation"[4] on the subject, that the auctioneer's use of a shill was not illegal. In addition, Pendleton said that Hinde had overpaid greatly for a slave in the recent past. On top of that, several other people not that long ago were paying unusually high prices for slaves and were not compensated for the excess amount paid. Pendleton thus argued that the seller should not be punished for taking advantage of an advantageous market.

The Court's Decision

Wythe said that using a by-bidder to artificially raise the winning bid at an auction was an unjustifiable deceit.[5] The by-bidder pretends to want to buy something, but does not, and through that deceit encourages someone else to pay more for the item instead. The deceit continues: the by-bidder is really just the seller in disguise. In a way, the by-bidder has a job similar to an actor; both use deception as the tool of their trade. An actor, though, is praised by his audience because he only cheats them of their perceived reality - here Wythe quotes from Hudibras.[6] A by-bidder, on the other hand, cheats their intended audience of their property, and is justly condemned.

The very nature of a by-bidder means that his offer is invalid. Pendleton seemed to worry about bidders conspiring to lower the slaves' sale price,[7] but the auctioneer could have allayed those fears by stating at the beginning of the auction that the slaves would not be sold below a certain price, rather than using the unethical method of employing a by-bidder.

As far as the other sellers who overpaid but did not receive relief were concerned, Wythe said there were two possibilities. One was that a by-bidder was involved, and the buyers simply have not yet applied to the courts for relief. The other possibility was that the auctioneer did not hire a by-bidder, and in such situations the Chancery Court could not grant relief. A judge in equity, Wythe said, did not have the power to appoint a guardian to such people to prevent them from making rash decisions (here Wythe refers to a section of Justinian's Institutes that says guardians may be appointed to handle the affairs of spendthrifts[8]).

Wythe found the use of a by-bidder especially egregious in this case because the auctioneer, Pendleton, and Lyons all knew that Hinde was likely to bid irrationally due to Hinde's wife's personal interest in the slaves.

Wythe rejected Pendleton's request to completely negate the sale. Wythe noted that the auctioneer's and by-bidder's actions made it impossible to determine what price Hinde would actually have paid at the auction, and said that instead Hinde should pay Pendleton the going market value in tobacco for the slaves at the time of the auction. Wythe said he would have entered a directive to determine what that market value was, but several months after the Chancery Court issued its decision, the parties agreed to have their case arbitrated by commissioners. Hinde agreed to pay Pendleton the amount ordered by the commissioners in exchange for the slaves.

Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe

Justinian's Institutes

Quotation in Wythe's opinion:

(b) Prodigi, licet majors viginti quinque annis nati sint, tamen in curatione sunt agnatorum, ex lege duodecim tabularum. sed solent Romae praefectus urbi, vel praetors, et in provinciis praesides, ex inquisition, eis curators dare. Justiniani institut. lib. I. tit. XXIII § III. Translation: “[Lunatics and] [p]rodigals, even though more than twenty-five years of age, are by the statute of the Twelve Tables placed under their agnates as curators; but now, as a rule, curators are appointed for them at Rome by the prefect of the city or praetor, and in the provinces by the governor, after inquiry into the case.[9]

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 354.

- ↑ Wythe 355.

- ↑ Wythe 355.

- ↑ Wythe 355.

- ↑ Wythe uses the Roman civil law term dolus malus. Wythe 355.

- ↑ "Doubtless the pleasure is as great/Of being cheated as to cheat". Samuel Butler, Hudibras, Pt. II, Cant. III, ln. 1-2 (London: Printed for John Baker, at the Black-Boy in Paternoster-Row 1709-10).

- ↑ Wythe does not make it entirely clear whether he thought Pendleton was worried about by-bidders being illegal or about getting a low price for the slaves; Wythe's language was ambiguous in this sentence of the opinion and could be read either way: "The inconvenience, if the practice of by-bidding be not tolerated, of which the active defendent seemed apprehensive, from combinations formed to the injury of the seller, may be honestly prevented by his preliminary declaration, that his property shall not be disposed of at less than a certain price. . ." Wythe 356. The more logical interpretation, though, is that Wythe thought Pendleton was worried about a potentially low price.

- ↑ "prodigi, licet maiores viginti quinque annis sint, tamen in curatione sunt adgnatorum ex lege duodecim tabularum. sed solent Romae praefectus urbis vel praetor et in provinciis praesides ex inquisitione eis dare curatores." Justinian Inst. 1.23.3.

- ↑ Ibid, 357. Translation: J.B. Moyle