The Enquirer

RICHMOND, 10th JUNE.

"Full of years; and full of honour."

On Sunday morning the 8th inst., departed this life, the venerable chancellor of the Richmond district, GEORGE WYTHE. Over the suspected causes of his death, let us for a moment draw the veil. Every situation in life has its rights and its duties. Let us therefore respect the rights of the accused.

But of the deep, the solemn, the almost unparalleled impression produced by his death, we may be permitted to speak.— Let the anxious solicitude manifested for his recovery; let that sorrow which buries beneath it all political distinction; let the solemn and lengthened procession which attended him to his grave; declare the loss which we have sustained. Kings may require mausoleums to consecrate their memory; saints may claim the privilege of canonization; but the venerable GEORGE WYTHE needs no other monument than the services rendered to his country, and the universal sorrow which that country sheds over his grave.

When the news of his death was made public, the bells of the city were set a tolling: the executive council assembled in their chamber, and determined on the following order of procession. It was published for the information of the citizens:

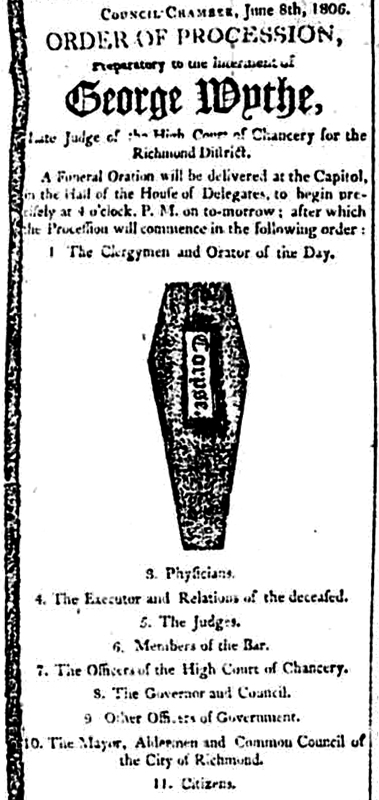

COUNCIL CHAMBER, June 8th, 1806.

ORDER OF PROCESSION,

Preparatory to the interment of

George Wythe,

Late Judge of the High Court of Chancery for the

Richmond District.

A Funeral Oration will be delivered at the Capitol, in the Hall of the House of Delegates, to begin precisely at 4 o'clock, P. M. on to-morrow; after which the Procession will commence in the following order:

1. The Clergymen and Orator of the Day.

[Drawing of a coffin labeled "Corpse."]

3. Physicians.

4. The Executor and Relations of the deceased.

5. The Judges.

6. Members of the Bar.

7. The Officers of the High Court of Chancery.

8. The Governor and Council.

9. Other Officers of Government.

10. The Mayor, Aldermen and Common Council of

the City of Richmond.

11. Citizens.

Need it be said, that the crowd which assembled in the capital was uncommonly numerous, and respectable? After the delivery of a funeral oration by Mr. Munford, a member of the executive council, the procession set out towards the church.— It is no disparagement to the virtues of the living, to assert, that there is not perhaps another man in Virginia, whom the same solemn procession would have attended to his grave.[3]

COMMUNICATION.

GEORGE WYTHE, the patriot, the philosopher, the philanthropist, is dead! Few have more strongly evinced the height of moral and intellectual excellence to which man is capable of ascending. In the knowledge of law he was indeed profound! Under a pressure of business at the bar before the revolution, which would have monopolized the attention of others, and unassisted by personal tuition from others, (for except as a lawyer he was self-taught) he acquired a knowledge of the ancient languages critically correct. Not only was the father of poetry his intimate companion, but the philosophers, historians, and even dramatic poets of antiquity were as familiar to him in their original dress, as were almost all the meritorious works of the day in his vernacular tongue. The writer of this sketch has heard him denominated emphatically "the walking library."

At a period of life, which in others would be deemed at least the verge of old age, he applied to mathematics and natural philosophy, both which sublime subjects he pursued with an ardor and depth seldom attained by a youthful student. When our rights were attacked by Great Britain, at the beginning of what, if unsuccessful, would have been termed a rebellion, but which we now boast of as a glorious revolution, even at that time venerable of age, he was respected for talents and correctness of demeanor, he assumed the then military garb and accoutrements of the volunteers, whom the divine spirit of patriotic enthusiasm had impelled to convene in the sacred cause of freedom.

The entreaties of the fond partner of his bosom could not retain him. He appeared before the soldiery, drawn up in military parade, on an alarm of the arrival of an inimical vessel. An awful silence pervaded the ranks. The spectators looked with admiration on him. At length the commanding officer, with surprise, enquired the cause of his appearing on the field thus accoutered! "I come, replied he, to offer my services to my country, and to do what you shall command." With difficulty he was prevailed on to desist from his design, under a persuasion that he could render more essential service to his country in the civil department.

The voice of his country called him to a seat in that Congress which declared the independence of America. He was not long an inactive member of that body. Much of the weight of the most arduous business was supported by him. He was a member of the grand convention which formed the constitution of the United States as well as of the state convention of Virginia, which ratified that instrument. The scrupulous devotion to justice, the strength of reasoning and depth of research which he manifested as chancellor, are known to all. Great he was in literature, in science and in law, fully impressed that "knowledge without morals is in vain," his superiority was more apparent in his conduct.

If to do no injury, but to do all possible good, is the summom bonam of morals, he reached it. Deeply informed in the various religions which existed in the world, his mind was liberal in the extreme to those who might differ from him. He brought into actual practice the purest and most useful tenets of morality and religion. If nature gave to him irritability, reason rendered him in general one of the calmest, the mildest of men. The infantine heart is not less sallied than that which beat in his bosom. Conscious of the equality of other's rights, there was generally a humility about him seldom found amongst those who were inferior to him in understanding and in morals. Every moment not beneficially employed, in his estimation, was criminally lost. He rejected with disdain every thing like excess, in which he comprehended all those things, not absolutely useful. His extraordinary temperance preserved or added to a strength of constitution which brought to his eightieth year, with few attacks of sickness. To his country he gave his life exclusively for many years.

He had been blest with the purest and warmest affection in the conjugal union; when this was dissolving, separating the cords tore his mind; when they were broken he bowed to the hand which had cut them; but did not fall. he who had not received from others, was liberal in communicating instruction. For some years the private tuition of youth was his favourite employment and amusement. The illustrious President of the United States with gratitude and affection, boasts himself a pupil of this modern Socrates. Hundreds in America are gratified in acknowledging themselves his disciples. From the President many of the various officers in the general government abroad and at home, and in the state government, owe to him their qualifications for discharging their duties. To him may be traced their conviction of the truth of the pure doctrines of republicanism. In politics, as in morals, he was with undeviating step pursued one course, and that the most correct. Was it wonderful then that not long before his death he should exclaim, "let me die righteous!" Thus lived and thus died this illustrious man.