"The Honest Lawyer: An Anecdote"

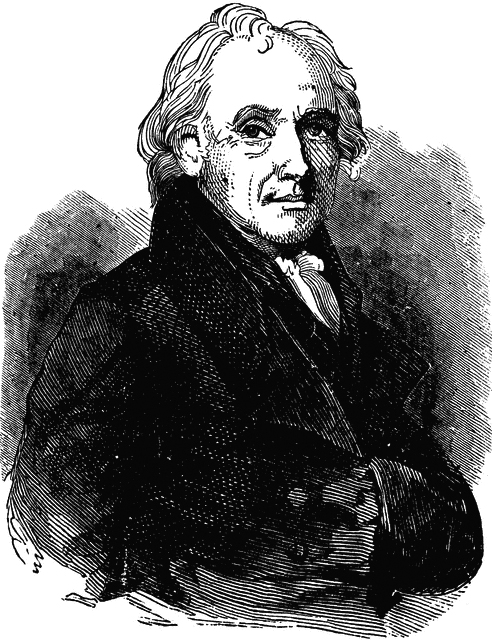

On Tuesday evening, July 1, 1806, The Times of Charleston, South Carolina, published an article by the Reverend M.L. Weems, titled "The Honest Lawyer, an Anecdote."[1] The article mentions a paragraph in a recent issue of The Times announcing the death of George Wythe, and Weems tells an anecdote of his dining with the Chancellor at his home in Richmond, Virginia, and provides what he calls a '"little moral eulogy': a short assessment of Wythe's irreproachable character. If Weems did visit Wythe at his home in Richmond, the meeting would have taken place in 1791 or later.

Parson Weems is best known for inventing the infamous "cherry-tree anecdote" in his biography of George Washington, and here he provides the supposed 'nearly word for word' text of a letter from Wythe to support his arguments. Addressed to one of Wythe's clients, Robert Alexander, Esq., it records Wythe's dismay that he feels 'altogether misled' in the facts of their case recently at trial (although he gives his client the benefit of the doubt), and declines to continue as doing so would go against 'God' and 'justice,' and returns his fee.

As a postscript, Weems provides a report of the ultimate results of the case: '"Bob was resolved, nolus bolus to go on with the suit and therefore gave the fifty dollar note to some other gentleman of the law, who pushed the matter for him and exactly with the success predicted by the good Mr. Wythe—the loss of his land with all costs.'

A portion of the article was published in the Washington City column of the National Intelligencer, and Washington Advertiser in the nation's capital on July 25, 1806,[2] and the full text was reprinted in 1916 in the William and Mary Quarterly.[3] An unknown person transcribed the portion of the article respecting Wythe's sentiment toward religion, the manuscript of which was reported in 1898 in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography.

Article text, 1 July 1806

Page 3

THE HONEST LAWYER,

AN ANECDOTE.

GLANCING an eye over one of your late papers, I accidentally caught the paragraph which stated the death of GEORGE WYTHE, Esq., Chancellor of Virginia. Some of your correspondents, very young and tender-hearted, perhaps, appeared quite galvanized by this piece of intelligence—but for my own part, getting now to be a little oldish myself, and daily, as becomes a stranger in Charleston, at this season, looking out for a squall of the same sort, I cannot say it was matter of much shock to me. I knew this much of Citizen Wythe, that great and good as he was, he was still no more than mortal man; and I also know that he was arrived to that full ripe state, at which philosophers and fruits begin, alike, to tremble to their fall; and when death, by a touch of his old thresher, with equal ease, brings down a chancellor or a cherry—and still less, if possible, was I grieved at his exit. What! grieved that this veteran of the law, after a life of glorious toil, to revive the golden age of justice on earth, was returned to the high courts of heaven—not, pale and trembling, like the wretched Jeffries, wet with widow's tears and blood of murdered patriots, to meet the tear-avenging God; but, bright in conscious integrity, with hands pure as the sweet palms which press the alabaster bottles of life, and in robes of innocence snow-white as those that angels wear, to meet the smiles of the Judge Supreme, and the acclamations of brother saints innumerable. Shall I grieve at this? At this, the loveliest sight ever yet placed before the eyes of sweetly sympathizing charity? Oh no. When a PLEADER, like him, forsakes this toilsome clod, to return to his native skies, let not the voice of grief be heard. Let us rather follow the steps of his departure with joy-gazing eyes, and shouts of praise to God, for a brother, who, after a life so honorable to human nature, and so instructive to the world, is going to his reward. And for the white stone that guards his sacred dust, 'tis wisdom's beacon to the young: Let it shine with the oil of gladness, suffer it not to be dimm'd with unseemly tears. No; give them to the vile attorney, who, for a fee, supported the villain's claims, and tore from the little weeping orphan, his cake and homely robe—give them to the infatuated miser, who, darkened at sight of a creditor, cursed his own signature if it compelled the payment of a dollar—and, unmoved by the calls of honor, still hugged to himself his precious pelf, content to live a scoundrel, provided he might but die rich—"guilt's blunder and the loudest laugh of hell." Give to such as these, your tears; they need them—but pour them not over the tomb of the sleeping Wythe, who while living, shewed how angels live. Having been often told, that though the honestest man in Virginia, yet he Wythe was not the most orthodox, I felt an ardent wish for an opportunity to learn his real sentiments about religion. That opportunity was soon offered. I fell in with him at Richmond—he invited me to dine with him. Being altogether granivorous himself, he gave me a dinner exactly to his own tooth; rice milk, improved with plumbs, sugar and nutmeg! Choice fare for a Bramin, or an Old Bachelor. It was over this demulcent diet, that I let drop expressions which shewed the current of my wishes; he took the hint, and with looks of complacency, and accents sweet as those of his native Mocking-Bird, he thus unbosomed himself:—

"Why, sir, as to religion, I have ever considered it as our best and greatest friend. Those glorious views which it gives to our relation to God, and of our destination to heaven, on the easy terms of a good life, unquestionably furnish the best of all motives to virtue; the strongest dissuasives from vice; and the richest cordial under trouble. Thus far, I suppose, we are all agreed; but not, perhaps, so entirely in another opinion, which is, that in the sight of God, moral character is the main point. This opinion, very clearly taught by Reason, is fully confirmed by Revelation, which every where teaches 'That the tree will be valued only for its good fruit,' and, that in the last day, according to our works of love, or of hatred, of mercy, or of cruelty, we shall sing with angels, or weep with devils. In short, the Christian Religion (the sweetest and sublimest in the world) labours, throughout, to infix in our hearts this great truth, that God is love—and that in exact proportion as we grow in love, we grow in his likeness; and consequently shall partake of his friendship and felicity forever. While others, therefore, have been beating their heads, or embittering their hearts, with disputes about 'forms of baptism,' and 'modes of faith,' it has always, thank God, struck me, as my great duty, constantly to think of this—God is love; and he that walketh in love, walketh in God and God in him."

This was the creed of Chancellor Wythe, the Hale, the Moore, of Virginia. His life was correspondingly amiable. His salary, as Chancellor of the State, was 350l. sterling, per annum!—not a tythe the cost of a diamond necklace for the favorite Miss of an European Nabob—indeed, hardly a month's allowance for one of their dog kennels! But to our honest Chancellor, it was enough, and to spare:—So cordially did he abhor the idea of giving to any man the pain of deception and disappointment, that he lived nobly independent with his little revenue, and no creditor ever went sad or angry from his door. With a fair claim on him, you might approach his simple dwelling with as light a heart as if you were skipping into the State Bank, with a check in your hand from John Blake, Esq. Exhibit your demands against him never so early, yet you never discomposed him—his eye lost none of its friendly lustre—his fine open brow contracted no cloud—no feature frowned the hateful Basilisk to kill the hope or to mar the pleasure of receiving your money. He never discharged a debt with those distressing sighs which often make a generous creditor wish he could afford to give it up; nor with that peevishness and passion which too plainly tell you, that he had rather you were at the devil.—

His philanthropy gave him that tender interest in your welfare, that "to owe you nothing but love," was to him, in lieu of a harsh precept, an heartfelt pleasure, and scarcely so much his duty as his delight.

The effect of this on the harmony and happiness of society, is incalculable. "Some men," says Lord Chesterfield, "oblige us more in denying, than others in doing, us a favor"—owing to the sweet spirit accompanying the denial.[4] Now if there be such a charm in this spirit (which is no other than that of love), that with it a denial obliges us more than a donation without it, then how delicious to the heart must the obligation be, when accompanied with that inexpressible charm of look, voice and manner, which even converts denial into obligation? Here lay the sort of this eminent Barrister, from whose fair example even pulpits might gain instruction. He always received his creditors with a countenance so refreshing—attended to his claim with such respectful readiness—and discharged it with a promptitude and pleasure so endearing—that his creditor actually felt himself, in turn, a debtor to the good Chancellor, whom he never left but with a throb of grateful sentiment, spontaneously breathing out his warmest benedictions on his head, and in as fervent prayers, that all men would, but like him, "live together in love, as dear children"; daily exalting each other's esteem, by duties, honorably performed; daily sweetening each other's spirits, by good offices, cheerfully rendered—that thus, ever filling each others hearts with love, they may strew over with flowers this life's paths, and substantially support each others steps to a better; where the recollection of such essential services past, will serve to give a brighter lustre to their love-beaming eyes, and to exalt to higher enjoyment their blissful communion forever.

In support of this little moral eulogy of Chancellor Wythe—in proof, I mean, that he possessed that fervent love, which gave him so tender an interest in the comfort of another, that no money could ever tempt him to invade it; take the following anecdote of him, and most exactly (in substance at least) as I received it from the Rev. Mr. Lee Massey, a first-rate Virginia clergyman, and from early life, the intimate of Mr. Wythe.[5]

"In the month of June, many years ago, I went," said Mr. Massey, "to dine with my friend, Bob Alexander." (Now, it may not much confuse the reader, to tell him that this same Bob Alexander, as Mr. Massey, in his familiar way, always called him, was a wealthy and worthy gentleman, living on the Potomac, and near Alexandria). Well, "while Mrs. Alexander, like Milton's Eve, 'on hospitable thoughts intent,' was preparing an elegant dinner, Bob and I took our chairs into the piazza, which commanded a very fine prospect indeed—full in our view lay the great Potomac, the mile-wide boundary between the sister states of Maryland and Virginia—on the Virginia side the rich bottoms lengthened out, far as the eye could see, were covered with crops of full ripe wheat, whose yellow tops rolling in ridges before the playful breeze, reflected the beams of the sun in sudden gleams of gold, brightening the day—on the Maryland side, a stately ridge of hills, high crowned with trees, formed as it were, a frowning guard to the great river, and threw its subliming shades, a striking contrast to the milder beauties of the opposite shore. Outspread between the two, lay the Potomac, whose little waves, just waked up by the young winds of summer, ran chasing each other along their sky-blue fields, often speaking their joy in bursts of snowy laughter. While thus we sat feasting on these richly varied and magnificent scenes, which the great Maker had so kindly spread before us, Bob's servant arrived from town with the newspapers, and a letter, which he handed to his master. Having hastily run it over, he exclaimed with great earnestness, Well, really Parson, this is strange, very strange! Why that George Wythe must certainly be either an angel or a fool."—'Not a fool, Bob,' said I; 'George Wythe is no fool'—'Well, that was never my opinion, neither, Parson; but what the plague are we to make of this confounded letter here—Suppose, Parson, you read it, and give me your opinion on it.' I took it, and with great pleasure read nearly word for word, as follows:—

- Robert Alexander, Esq.

SIR.—The suit wherein you were pleased to do me the honor to engage my services, was last week brought to trial, and has fully satisfied me that you were entirely in the wrong. Knowing you to be a perfectly honest man, I conclude that you have somehow or other been misled. At any rate I find I have altogether been misled in the affair, and therefore insist on washing my hands of it immediately. In so doing I trust I shall not be charged with any failure of duty to you. As your lawyer 'tis true I owe you every thing—everything consistent with justice;—against her, nothing; nor ever can owe. For justice is appointed of God, the golden rule of all order throughout the universe, and therefore, as involving the greatest of all possible good to his creatures, it must be of all things the dearest to HIMSELF. He therefore, who knowingly acts against justice, is a rebel against God, and a premeditated murderer of mankind. Of this crime (which worlds could not tempt me to commit) I should certainly be guilty, were I, under my present convictions, to go on with your suit. I hasten therefore to enclose you the fifty dollar note you gave me as a fee, and with it my advice, that you compromise the matter on the best terms you can.

I have just to add, that as conscience will not allow me to say any thing for you, honor forbids that I should say any thing against you. But, by all means, compromise and save the costs. Adieu, wishing you that inward sunshine, which nothing outward can darken,

- I remain, dear sir, your's

- GEO. WYTHE.

For the sake of those who may wish to know whether the advice, in this extraordinary letter, was followed or not, I beg leave to add, that it was not followed. Mr. Massey told me, that his friend Bob was resolved, nolus volus, to go on with the suit, and therefore gave the fifty dollar note to some other gentleman of the law, who pushed the matter for him, and exactly with the success predicted by the good Mr. Wythe—the loss of his land, with all costs! "Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth."

M. L. Weems.

See also

- Chancellor Wythe's Opinion Respecting Religion

- Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire

- Republican Court

References

- ↑ M.L. Weems, "The Honest Lawyer, an Anecdote," The Times (Charleston, SC), July 1, 1806, 3.

- ↑ M.L. Weems, National Intelligencer, and Washington Advertiser (Washington, D.C.), July 25, 1806, 1.

- ↑ D.R. Anderson, "Chancellor Wythe and Parson Weems," William and Mary Quarterly, 1st Series, 25 (July 1916), 13-20.

- ↑ Lord Chesterfield's Letters to His Son, Letter CLXIII: 'In business how prevalent are the graces! how detrimental is the want of them! By the help of these, I have known some men refuse favours, less offensively than others granted them.'

- ↑ 'Reverend Lee Massey, mentioned in Weems' letter, was rector of Truro Parish while Washington was a vestryman. He was a friend of Washington, and legal adviser of George Mason.' Anderson, "Chancellor Wythe," 14-15.