Elizabeth Taliaferro Wythe

Elizabeth Taliaferro Wythe (c. 1739 – August 14, 1787) was born in Virginia, probably at the family plantation of Powhatan, outside Williamsburg. Elizabeth became the second wife of George Wythe in 1754. Through her Taliaferro family, George Wythe became a wealthy man. At the time of their marriage Elizabeth was either 14 or 15 years old which was a nuptial age not considered unusual at the time. Elizabeth and George were the parents of one child which died in infancy. Unfortunately little is known about Elizabeth in the historical record but by all accounts Elizabeth and George were happily married.

Richard Taliaferro gave his daughter Elizabeth and her husband, George, the Williamsburg home he had built for himself. Elizabeth (Taliaferro) Wythe and her husband, George Wythe, lived in the home for more than thirty years. In 1779, Richard Taliaferro's will gave George and Elizabeth use of the property for life. Elizabeth died in 1787, and George moved to Richmond in 1791 to serve as a judge on Virginia's court of Chancery.

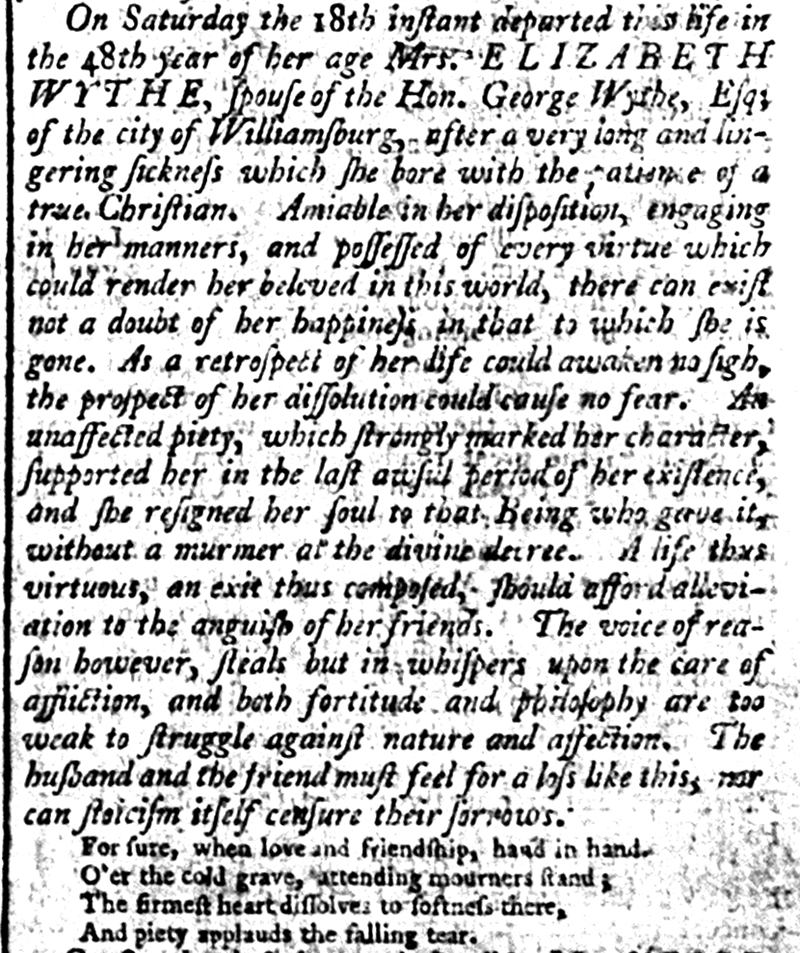

Elizabeth's obituary, probably written by George Wythe, most likely appeared in the Richmond papers in the weeks following her death.[1] The quoted poem is from "On the Death of Lady Anson," by David Mallet (1761).[2]

Obituary, Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser, 23 August 1787

Page 2

On Saturday the 18th instant departed this life in the 48th year of her age Mrs. ELIZABETH WYTHE spouse of the Hon. George Wythe, Esq. of the city of Williamsburg, after a very long and lingering sickness which she bore with the patience of a true Christian. Amiable in her disposition, engaging in her manners, and possessed of every virtue which could render her beloved in this world, there can exist not a doubt of her happiness in that to which she is gone. As a retrospect of her life could no sigh, the prospect of her dissolution could cause no fear. An unaffected piety, which strongly her character, supported her in the last awful period of her existence, and she resigned her soul to that being who gave it without a murmur at the divine decree. A life thus virtuous, an exit thus completed, should afford alleviation to the anguish of her friends. The voice of reason however, steals but in whispers upon the care of affliction, and both fortitude and philosophy are too weak to struggle against nature and affection. The husband and the friend must feel for a loss like this, nor can stoicism itself censure their sorrows.

For sure, when love and friendship, hand in hand,

O'er the cold grave, attending mourners stand;

The firmest heart dissolves to softness there,

and piety applauds the falling tear.

See also

References

- ↑ Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser (Richmond, VA), August 23, 1787, 2; Virginia Independent Chronicle; (Richmond, VA), August 23, 1787, 3; The Virginia Gazette, and Petersburg Intelligencer, 30 August 1787.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, ed. The Works of the English Poets, vol. 53, The Poems of Dyer and Mallet (London: J. Rivinginton, 1779), 329-332.