Characteristicks, of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times &c.

by Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury

| Characteristicks | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury | |

| Date | Unknown | |

| Edition | Precise edition unknown | |

| Language | English | |

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713), firstborn son of the 2nd Earl of Shaftesbury, was a pupil of John Locke’s in the early 1670s.[1] While Shaftesbury did not always agree with Locke’s philosophies, his influence no doubt helped to shape Shaftesbury as an intellectual.[2] After a tour of continental Europe in the 1680s, Cooper returned to England and eventually began a three-year stint in the House of Commons from 1695-1698.[3] Though his career there was largely uneventful, it is noteworthy for his support of the Treason Bill, which provided legal counsel for those accused of the crime.[4] When Cooper rose to speak in favor of the bill, he either feigned fright at speaking to the assembly or was actually frightened, and had to take a moment to compose himself in front of the body.[5] Once ready, he then spoke of the need for the accused to have counsel in front of the judges trying their case, because he, innocent and not even accused of treason, as well as a Member of Parliament, was still placed in a state of fright when compelled to speak before their authority.[6] The bill passed in no small part due to this rhetorical flourish. Afterwards, he refused to stand for the House of Commons again, and instead stepped down as the body dissolved. A year later, in 1699, his father died and Cooper gained his seat in the House of Lords, where he served actively until William III’s death in 1702.[7]

Cooper was single most of his life, which gave rise to questions regarding his sexuality that his own writings do not dispel.[8] He did, however, recognize his duty to his family to further his line, as evidenced by a letter to his brother, Maurice, in 1705.[9] In 1709, he married a Jane Ewer, and by 1711 she bore him a son, who would become Anthony Ashley Cooper, 4th Earl of Shaftesbury.[10] In the middle of 1711 he left England for good, and late that year established a residence in Chiaia, Italy. He lived there until his death in 1713.[11] His remains were returned to England and interred in the chapel of Wimborne St. Giles.[12]

Characteristicks, of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times &c., a collection of Cooper's more influential essays, was first published in 1711.[13] Cooper made extensive revisions for the second edition which was released over a year after his death in 1714.[14] It contained multiple engravings in the second volume, included for illustrative and demonstrative purposes.[15] Over the next 60 years, nine more editions surfaced in England.[16] The work itself was intended to serve as a guide to the reader on how to live a morally sound life, and covers a myriad of topics, from masculinity to the arts.[17] Containing nearly a quarter-million words, the manuscript itself is often split into three volumes.[18] The first volume contains what amounts to a foundation of principles that are discussed in more depth in the second volume. The third volume then contains meandering writings intended to clarify the first two volumes.[19] The work is notable for both its novel approach in addressing moralistic thinking and its influence on future philosophers. Cooper's work was one of the first of its kind to explore moral principles divorced from the typical Christian framework that often accompanied them.[20] Instead, Cooper framed his justification for moral principles based on natural propensities for affection between individuals.[21] Characteristicks, of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times &c. influenced many prominent philosophers of later generations, including David Hume and, to a lesser extent, Immanuel Kant.[22]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

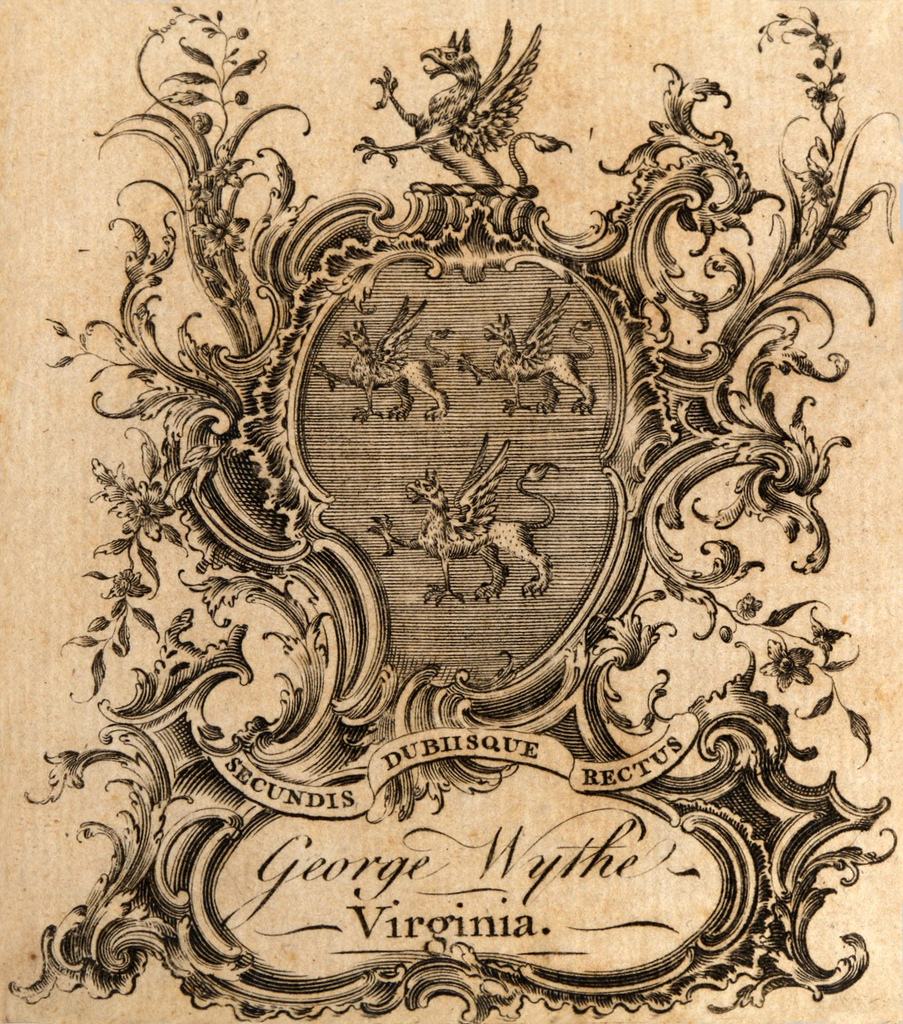

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Shaftesbury’s Characteristics. 3.v. 12mo." and given by Thomas Jefferson to his son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph. Later appears on Randolph's 1832 estate inventory as "Shaftsbury's Essays 2 [vols.], $1.00." George Wythe's Library[23] on LibraryThing indicates "Precise edition unknown. Several duodecimo editions were published, the first in 1733." Brown's Bibliography[24] lists the choice of either the 2nd edition published in London (1714-715)[25] or the Foulis edition published in Glasgow (1743-1745)[26] based on copies owned by Thomas Jefferson. He also notes "Since Wythe favored published works from Foulis, he may have owned that edition. However, we cannot prove one way or the other which edition he owned."[27]

The Wolf Law Library has not found an available copy of Shaftesbury's Characteristics, but would prefer the Foulis edition if available.

See also

References

- ↑ Lawrence E. Klein, "Cooper, Anthony Ashley, third earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed December 4 2015.

- ↑ McAteer, John. "The Third Earl of Shaftesbury (1671—1713)." Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. Accessed October 23, 2023. https://iep.utm.edu/shaftes/.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3d Earl of," in The Columbia Encyclopedia (New York, NY: Columbia University Press).

- ↑ Lawrence E. Klein, "Review of Anthony Ashley Cooper, Third Earl of Shaftesbury, Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times edited by Philip Ayres," 64, no. 3/4 Huntington Library Quarterly (2001): 529.

- ↑ Isabel Rivers, "Review of Anthony Ashley Cooper, Third Earl of Shaftesbury, Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times edited by Philip Ayres," 51, no.204 new series The Review of English Studies (Nov. 2000): 620.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Klein, "Review," 531.

- ↑ Ibid., 532

- ↑ Rivers, "Review," 617.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on July 18, 2023.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 2:13 [no.1258]. Jefferson sold a copy of the London edition to the Library of Congress in 1815, but it includes no markings suggesting prior Wythe ownership.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson's Library: A Catalog with the Entries in His Own Order, ed. by James Gilreath and Douglas L. Wilson (Washington: Library of Congress, 1989): 55.

- ↑ Brown.