Hai tou Anakreontos ōdai kai ta tēs Sapphous kai ta tou Alkaiou Leipsana = Anacreontis Carmina cum Sapphonis, et Alcaei fragmentis

by Anacreon, Sappho, and Alcaeus

| Hai tou Anakreontos | ||

|

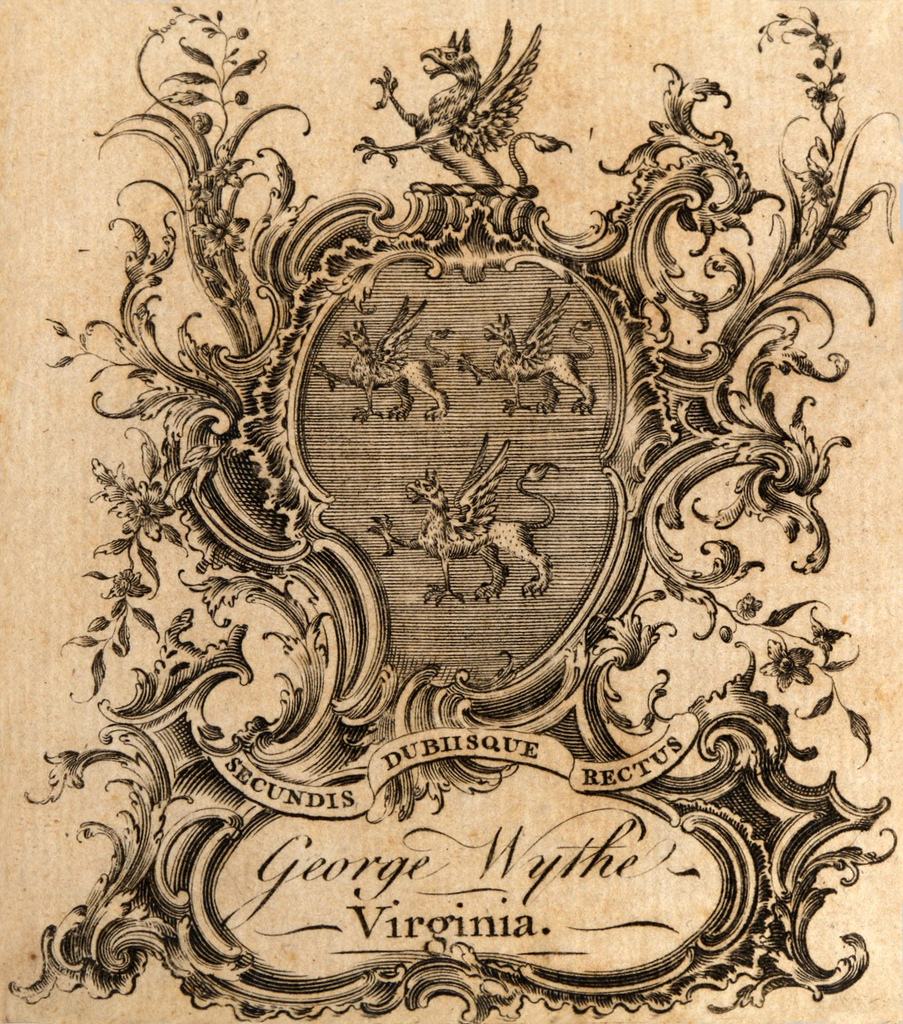

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Anacreon, Sappho, and Alcaeus | |

| Edition | Precise edition unknown | |

| Desc. | 12mo | |

Anacreon (582 BCE–485 BCE) was a Greek lyric poet born in Teos, an Ionian city on the coast of Asia Minor.[1] He likely moved to Thrace in 545 BCE with others from his city when it was attacked by Persians. He then moved to Samos, to Athens, and possibly again to Thessaly, seeking a safe place to write his poems as his patrons (including Polycrates, tyrant of Samos, and Hipparchus, brother of Athenian tyrant Hippias) kept being murdered.[2] It is unknown where Anacreon died,[3] though he lived to the unusually advanced age of 85.[4]

Few of Anacreon’s works survive, but those that do focus on wine, love (homosexual and heterosexual), and the overall pleasures of the legendary Roman symposium.[5] Anacreon used various techniques in his writings, including self-deprecation and irony.[6] The collection of miscellaneous Greek poems from the Hellenistic Age and beyond known as the Anacreontea[7] was “mistakenly labeled” with Anacreon’s name. Despite later appreciation for Anacreon’s true poems, his works were not appreciated during his lifetime.[8]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

See also

- Anacreontis Odaria ad Textus Barnesiani Fidem Emendata

- Jefferson Inventory

- Odes of Anacreon

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ " Ana'creon” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Marty Roth, "Anacreon’ and Drink Poetry; or, the Art of Feeling Very Very Good,” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 42, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 314.

- ↑ "Anacreon" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).]

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Roth, "Anacreon’ and Drink Poetry; or, the Art of Feeling Very Very Good,” 317.