Jefferson-Tyler Correspondence

Letter from Governor John Tyler to Thomas Jefferson

"John Tyler to Thomas Jefferson, November 12, 1810, p. 1." Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.]

"John Tyler to Thomas Jefferson, November 12, 1810, p. 2." Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.]

Richmond, Nov. 12, 1810Dear Sir,

Perhaps Mr. Ritchie, before this time, has informed you of his having possession of Mr. Wythe's manuscript lectures delivered at William and Mary College while he was professor of law and politics at that place. They are highly worthy of publication, and but for the delicacy of sentiment and the remarkably modest and unassuming character of that valuable and virtuous citizen, they would have made their way in the world before this. It is a pity they should be lost to society, and such a monument of his memory be neglected. As you are entitled to it by his will (I am informed), as composing a part of his library, could you not find leisure time enough to examine it and supply some omissions which now and then are met with, I suppose from accident, or from not having time to correct and improve the whole as he intended?

Judge Roane has read them, or most of them, and is highly pleased with them, thinks they will be very valuable, there being so much of his own sound reasoning upon great principles, and not a mere servile copy of Blackstone and other British commentators,—a good many of his own thoughts on our constitutions and the necessary changes they have begotten, with that spirit of freedom which always marked his opinions.

I have not had an opportunity of reading them, which I would have done with great delight, but these remarks are made from Judge Roane's account of them to me, who seemed to think, as I do, that you alone should have the sole dominion over them, and should send them to posterity under your patronage.

It will afford a lasting evidence to the world, among much other, of your remembrance of the man who was always dear to you and his country. I do not see why an American Aristides should not be known to future ages. Had he been a vain egoist his sentiments would have been often seen on paper; and perhaps he erred in this respect, as the good and great should always leave their precepts and opinions for the benefit of mankind.

Mr. Wm. Crane gave it to Mr. Ritchie, who I suppose got it from Mr. Duval, who always had access to Mr. Wythe's library, and was much in his confidence.

I hope you are quite as happy as mortality is susceptible of, though not quite dissolved; and that you may remain so for many years, is the sincere wish of your most obedient humble servant.

Jn. Tyler[1]

Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Governor John Tyler

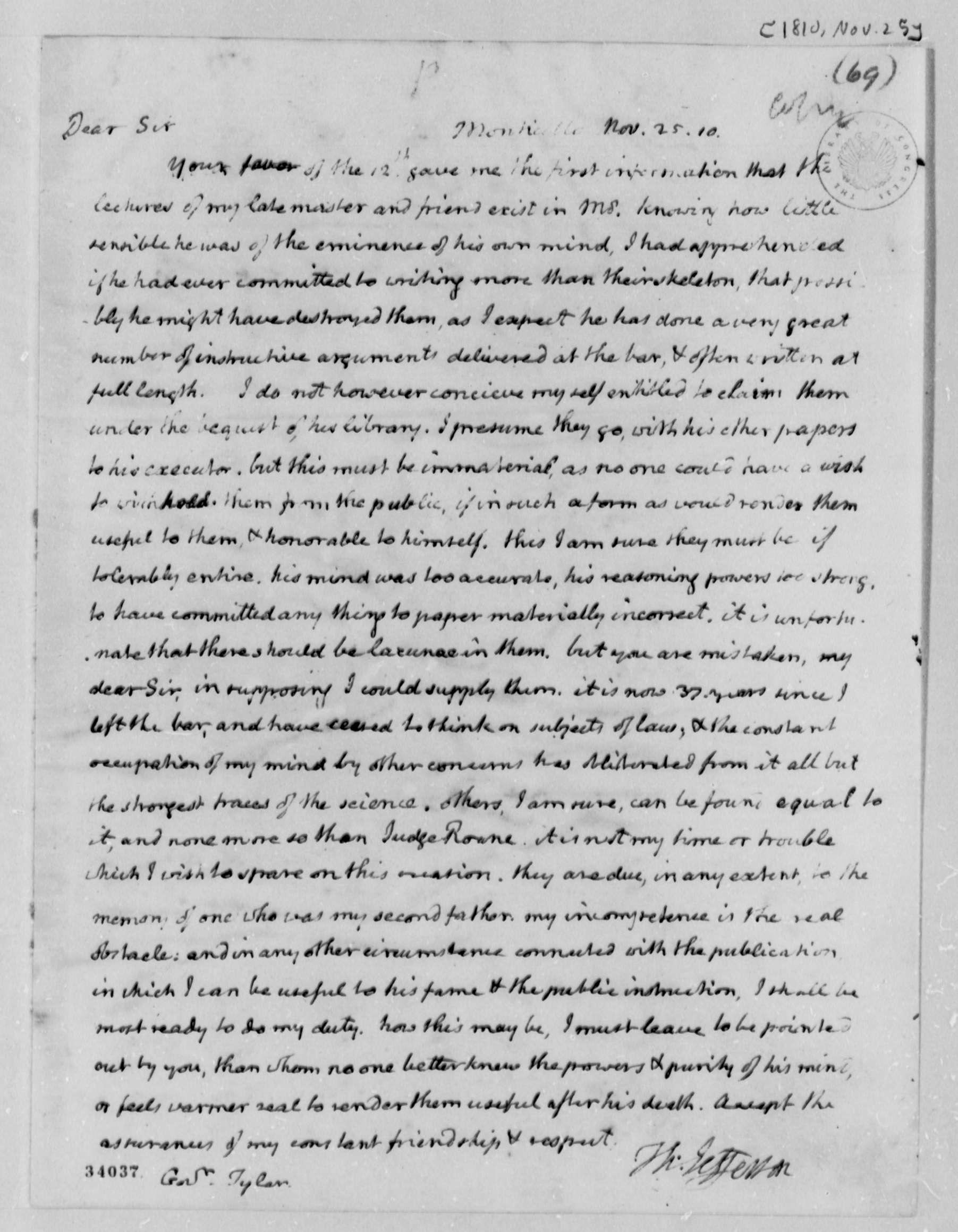

"Thomas Jefferson to John Tyler, November 25, 1810." Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.]

Monticello, Nov. 25, 10.Dear Sir,

Your favor of the 12th gave me the first information that the lectures of my late master and friend exist in MS. Knowing how little sensible he was of the eminence of his own mind, I had apprehended, if he had ever committed to writing more than their skeleton, that possibly he might have destroyed them, as I expect he has done a very great number of instructive arguments delivered at the bar, and often written at full length. I do not however conceive myself entitled to claim them under the bequest of his library. I presume they go, with his other papers to his executor. But this must be immaterial, as no one could have a wish to withhold them from the public, if in such a form as would render them useful to them, & honorable to himself. This I am sure they must be if tolerably entire. His mind was too accurate, his reasoning powers too strong, to have committed anything to paper materially incorrect. It is unfortunate that there should be lacunae in them. But you are mistaken, my dear sir, in supposing I could supply them. It is now 37 years since I left the bar, and have ceased to think on subjects of law; & the constant occupation of my mind by other concerns has obliterated from it all but the strongest traces of the science. Others, I am sure, can be found equal to it, and none more so than Judge Roane. It is not my time or trouble which I wish to spare on this occasion. They are due, in any extent, to the memory of one who was my second father, my incompetence is the real obstacle: and in any other circumstance connected with the publication, in which I can be useful to his fame, and the public instruction, I shall be most ready to do my duty. How this may be, I must leave to be pointed out by you, than whom no one better knew the powers & purity of his mind, or feels warmer zeal to render them useful after his death. Accept the assurances of my constant friendship & respect.

Th. Jefferson[2]

References

- ↑ Lyon G. Tyler, The Letters and Times of the Tylers, (Richmond, Va.: Whittet & Shepperson, 1884), 249-250.

- ↑ Paul Leicester Ford, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1905), 11:109.