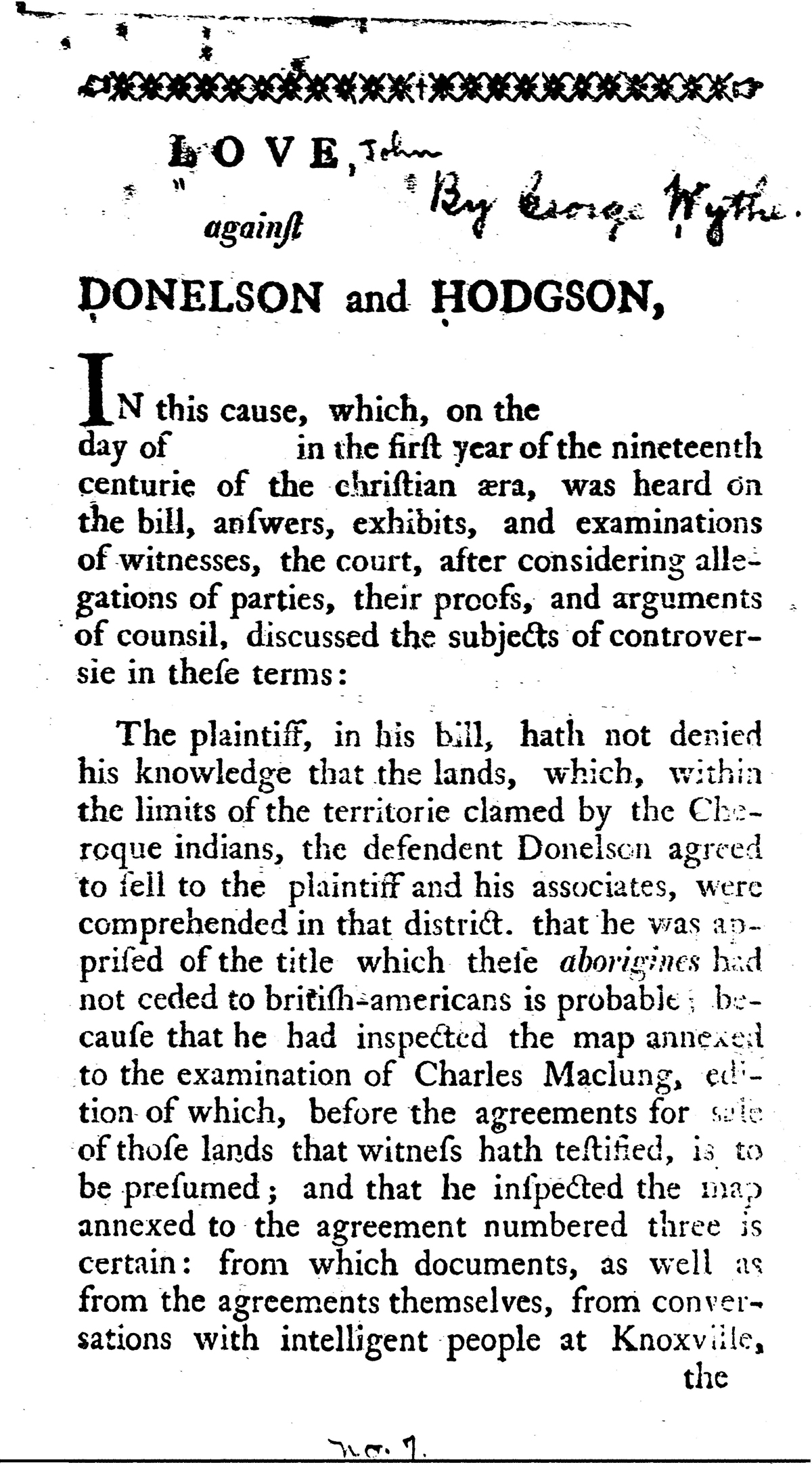

Love v. Donelson

Love v. Donelson (1801)[1] involved a buyer of land who paid for his purchase with a bond. The buyer was entitled to a partial discount against the original seller of the land, but the original seller transferred the bond to another person who did not know about the possibility of a refund. The court discussed whether the new owner of the bond had to give the original buyer of the land the same discount as the original seller. The opinion is an example of Wythe severely criticizing the Virginia Supreme Court for their interpretation of a statute, and also features Wythe possibly misquoting Aristotle indirectly.

Background

Love bought land from Donelson. Love knew, both through talking with relevant people in Knoxville (in what is now Tennessee) and by examining the map attached to the sales contract, that the land he bought was part of territory that the Cherokee Nation claimed and had not ceded to Great Britain or to the United States. In the contract, Donelson said that he would warrant and sponsor Love's claim against anyone, including the Cherokee. Love paid for the land in the form of a bond, which Donelson later sold to Hodgson. Hodgson claimed that he did not know about Donelson's promise to warrant the land against other claims when he bought the bond.

The American government ceded at least part of Love's land to the Cherokee under a treaty,[2]

Hodgson filed suit and won a judgment to claim payment on the bond in 1796. Love filed a bill with the High Court of Chancery to enjoin that judgment so that Love could reduce his required payment in proportion to the amount of land that was ceded to the Cherokee.

Love v. Donelson was not reported in the second edition of Wythe's Reports, in 1852.[3][4] Wythe's opinion was published as a supplemental pamphlet, Love against Donelson, in 1801 or later, most likely printed by Thomas Nicolson of Richmond, Virginia, who had published Wythe's Reports in 1795.[5]

The Court's Decision

Wythe dismissed Love's petition, with costs. Wythe said that Love's relief against Donelson was an equitable one, not a legal one, and that equitable relief only transfers to the purchaser of a bond if that purchaser knew that the relief existed when they bought the bond. Wythe acknowleged, however, that the Virginia Supreme Court had held differently, and devoted the bulk of the opinion to a discussion of why the judges from that court were in error.

Wythe's Discussion

Wythe noted that if Hodgson had known about Donelson's promise to warrant the land against other claims or that Love did not have proper title to that land when Hodgson accepted the bond, then Love would be entitled to the relief he requested. The evidence, however, did not show that Hodgson knew either of these things when he purchased it. Therefore, Wythe said, the equitable element of Love's claim sticks to his legal claim against Hodgson no better than the feet and toes of Nebuchadnezzar's statue, made partly of iron and partly of clay — partly strong, and partly broken.[6]

Wythe pointed to one of his earlier decisions, Overstreet v. Randolph, in which he stated that the debtor on a payment bond could not get relief against someone who purchased a bond from the original creditor of a bond if that purchaser did not know about the unfairness involved in the bond's original creation.[7] However, Wythe also noted the Virginia Supreme Court's decision in Norton v. Rose, which stated that the person who is assigned a bond or obligation is subject to everything the original creditor was subject to.[8]

In classic Wythe form, the bulk of the opinion in Love involves Wythe dissecting the Virginia Supreme Court's Norton v. Rose opinion, practically line by line (it is presumably no coincidence that the Norton opinion reversed one of Wythe's decrees, as Wythe takes pains to point out multiple times). Wythe's primary criticism of the Supreme Court's ruling in Norton is that the judges created a legislative intent from whole cloth, reading meaning into the language of the relevant statute[9] that was not there.

Judge Roane, "far the best of augurs"

Wythe mockingly compares Judge Spencer Roane's ability to divine the legislature's intent to that of "Calchas, son of Thestor, far the best of augurs."[10]

Judge Lyons, architect rules, and a quote of Aristotle that wasn't

Wythe later turns his attention to Judge Peter Lyons's statement in Norton that "the accuracy of the principle (Wythe describes) is not questioned; its application to (Norton) is."[11] Wythe criticizes this statement by quoting a passage from Book II, Chapter III of Jean-Jacques Barthelemy's Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece. In the passage, Barthelemy says Aristotle the residents of the island of Lesbos as people who "relaxed their principles of morality, as occasion required, and adapted themselves to circumstances with as much facility as they open and shut certain leaden rules used by their architects".[12] The "leaden rules" refer to flexible rulers used by architects to measure irregular curves. These rulers were called "Lesbian rules" because they were originally made of lead from the island of Lesbos. A handwritten note in Wythe's copy of the opinion cites a page from John Taylor's Elements of the Civil Law that mentions the "Norma Lesbia, which shapes itself to every thing."[13] Wythe concludes his opinion by stating that the laws of equity are not as flexible as those leaden architects' rules, and that in a situation such as the one currently before the Chancery, in which Love's and Hodgson's equities are equal, but Hodgson's legal rights are greater, Hodgson must win.

In a footnote, Wythe describes a discussion he had with "Watkins Leigh, one of William and Mary's ornaments",[14] presumably referring to Benjamin Watkins Leigh.[15] Leigh contended that Aristotle said nothing about the people of Lesbos "relax(ing) their principles of morality", and that Barthelemy probably got that idea instead from Siculus Didorus. Aristotle does mention the Lesbian Rule in Book V, Chapter 10, of Nicomachean Ethics, but in a positive sense - the opposite of Wythe's intent of alluding to the Rule.[16]

Wythe conceded that he "had not then consulted Aristotle" when writing the opinion, but says that his reading of Siculus shows that that book did not opine on the moral character of the people of that island, either. Wythe concludes his footnote by saying "that (the people of Lesbos) were not slandered by Barthelemy seemeth to be proved by other authors."[17] The admission by such a great scholar of the Greek and Roman classics as Wythe that he did not bother to verify the citation to Aristotle, along with an offhanded assertion that other, unnamed authors said the same thing anyway, are puzzling.

Wythe's conclusion from Horace

Wythe concludes his opinion with a quote from Horace's Satires. Wythe has "no doubt" that Rose will appeal the Chancery Court's decision, and Wythe expresses the hope that the Virginia Supreme Court will take the opportunity to uphold Wythe and overrule the precedent they set in Norton v. Rose. Such a decision, Wythe said, would only be relished by uni aequus virtuti atque ejus amicis -- "a friend equally to virtue and to virtue's friends".[18]

See also

References

- Jump up ↑ George Wythe, Love, against Donelson and Hodgson (Richmond, VA: Thomas Nicolson, 1801?).

- Jump up ↑ Wythe does not specify which treaty. He might be referring to the [[wikipedia:Treaty of Holston|]] of 1791, but Wythe talks about land "abdicated by the british americans" (Love, against Donelson and Hodgson at 2), which implies that it was a treaty from the pre-Revolutionary days. Perhaps the [[wikipedia:Treaty of Hard Labour|]] or the [[wikipedia:Treaty of Lochaber|]]?

- Jump up ↑ Benjamin Blake Minor, ed., Decisions of Cases In Virginia, By the High Court Chancery, with Remarks Upon Decrees By the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, by George Wythe (Richmond, Virginia: J.W. Randolph, 1852), xli.

- Jump up ↑ Minor had access to a bound volume of pamphlets which had belonged to James Madison, and was then in the possession of William Green of Culpeper, Virginia. The Catalogue of the Choice and Extensive Law and Miscellaneous Library of the late Hon. William Green, LL.D.,... to be sold by Auction, January 18th, 1881, at Richmond, VA. (Richmond: John E. Laughton, Jr., 1881), lists the volume as follows (p. 200):

2325. WYTHE'S REPORTS. Aylett & Aylett, Richmond: 1796; Field & Harrison, Richmond: 1796. WYTHE (GEO.). Case upon the Statute for Distribution, Richmond: 1796. Wilkins & John Taylor, et als.; Fowler & Saunders. In one vol., 12mo. Auto. of President James Madison. Ms. notes. A rare collection of the Original Imprints, supposed by the late possessor to be unique.

- Jump up ↑ Charles Evans, American Bibliography, vol. 11 (1942). Evans mistakenly gives the date of publication of Love against Donelson as 1796.

- Jump up ↑ Love, against Donelson and Hodgson, 24, referring to Daniel 2: 33, 42.

- Jump up ↑ Overstreet v. Randolph, George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 47.

- Jump up ↑ Norton v. Rose, 2 Va. (2 Wash.) 254 (1796).

- Jump up ↑ Ch. 33, October 1748 Session, "An act for ascertaining the damage upon protested bills of exchange; and for the better recovery of debts due on promissory notes; and for the assignment of bonds, obligations, and notes," William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; being a collection of all the laws of Virginia, from the first session of the Legislature in the year 1619 (Richmond, VA: Printed for the Editor at the Franklin Press -- W. W. Gray, Printer, 1819), 6: 85.

- Jump up ↑ Love, against Donelson and Hodgson, 14. Calchas was a seer from Greek myth who got his gift for divining from Apollo.

- Jump up ↑ Love, against Donelson and Hodgson, 32.

- Jump up ↑ Jean-Jacques Barthelemy, Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece (London: Printed for J. Johnson, et al., 4th ed. 1806), 2: 52-3, available at Villanova University Digital Library (last visited March 27, 2015).

- Jump up ↑ John Taylor, Elements of the Civil Law (London: Charles Bathurst, 3d ed. 1769), 482.

- Jump up ↑ Love, against Donelson and Hodgson, 32.

- Jump up ↑ B.W. Leigh graduated from William & Mary in 1802 and "studied law" according to his Congressional biography. Wythe describing Leigh as "the ingenious student" implies that Wythe taught Leigh, but we have no definite proof one way or the other.

- Jump up ↑ "In fact this is the reason why all things are not determined by law, that about some things it is impossible to lay down a law, so that a decree is needed. For when the thing is indefinite the rule also is indefinite, like the leaden rule used in making the Lesbian moulding; the rule adapts itself to the shape of the stone and is not rigid, and so too the decree is adapted to the facts." Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book V, Ch. 10, as found in The Internet Classics Archive (last visited March 26, 2015).

- Jump up ↑ Love, against Donelson and Hodgson, 32.

- Jump up ↑ Love, against Donelson and Hodgson, 33, quoting Horatii Satirarum, Book II, Satire 1, Line 70.