Fowler v. Saunders

Fowler v. Saunders, Wythe 322 (1798),[1] was a dispute over who owned slaves in which Wythe interpreted the intended meaning and application of Virginia statutes.

Background

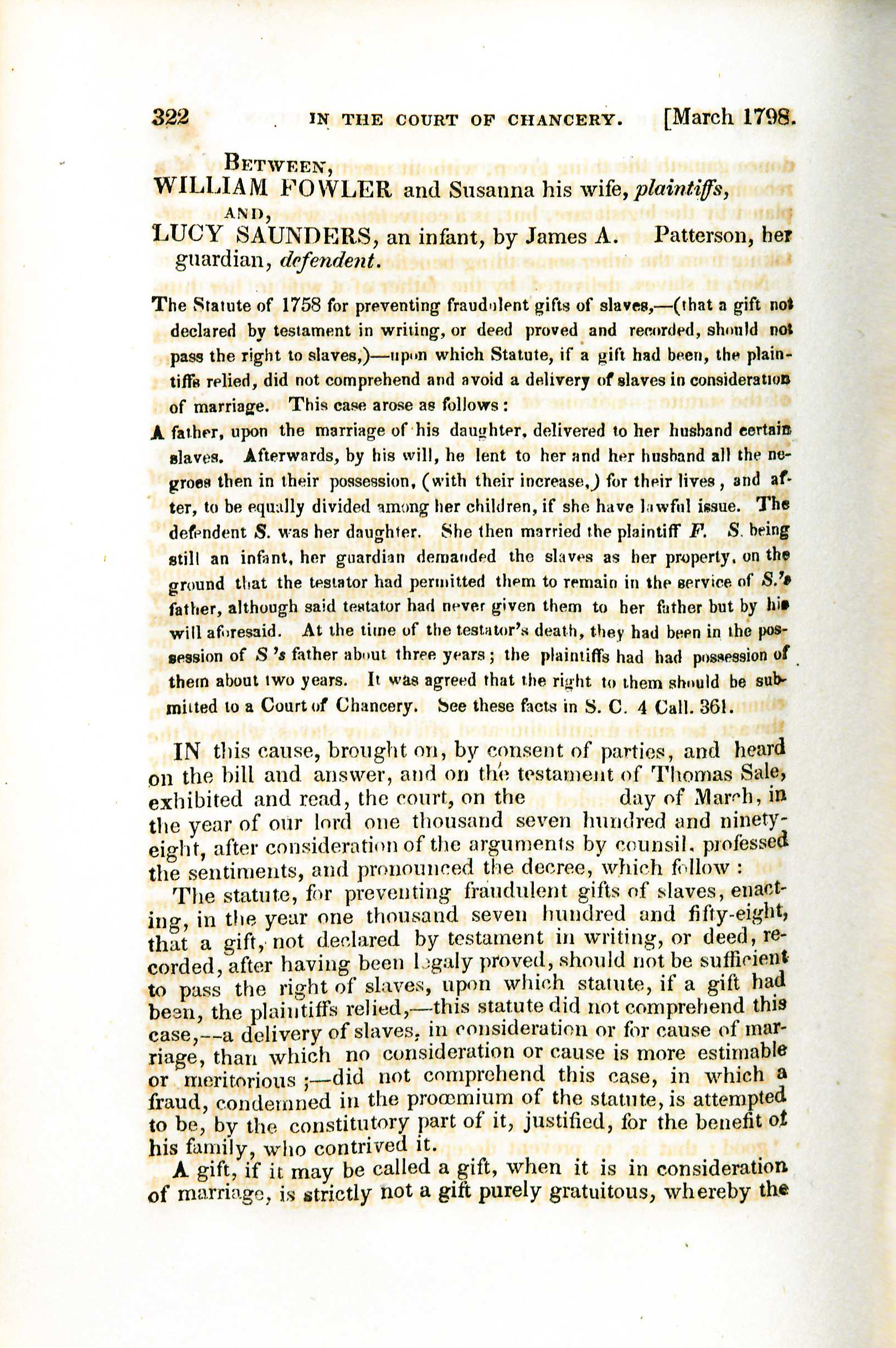

Thomas Sale sent his daughter, Susanna, and her husband, Alexander Saunders, a number of slaves following their marriage. In his will Sale afforded the Saunderses a life interest in those slaves and any children those slaves may produce. Upon Sale's death the slaves and their descendants were to pass to his daughter's children. Susanna produced a daughter, Lucy Saunders, but later married William Fowler following Alexander Saunders's death. Following their marriage Fowler obtained possession of the slaves. Instead of the slaves passing to Lucy after Sale's death, the Fowlers retained possession.

James Patterson, Lucy's guardian, supposedly claimed that Lucy was entitled to the slaves now that Sale had passed on as afforded to her in his will. The Fowlers filed suit in the High Court of Chancery to settle the issue. The court found in Lucy's favor, and affirmed the dispensations in Sale's will.

The Court's Decision

In 1758 the Virginia legislature enacted a statute providing that a gift of slaves would not be valid without the provision of a writing passing title and right to those slaves.[2] The statute was intended to prevent attempts to retain the legal rights to a group of slaves while at once dispensing of physical possession, an act which was deemed to defraud the public as to whom the slaves belonged.

In 1787, the legislature passed a declaratory statute (intended to explain a previous law's meaning) stating that the 1758 Act did not require a gift of slaves to be confirmed in writing if it was a gift from a person to an heir and the heir kept possession of the slaves after the gift so that the heir was considered the slaves' owner.[3]

Although the 1758 and 1787 statutes did not speak to cases in which the slaves were gifted or transferred in consideration of marriage, the court depended on them for its decision. Wythe said that the 1758 Act was only intended to prevent fraudulent situations where a person pretends to give away ownership of slaves while actually retaining it; the 1787 Act makes that clear. The Fowlers argued that they married before 1787, so that Act did not apply to them. Wythe said that because the 1787 Act was a declaratory act, it was only restating the law as it already was under the 1758 Act, rather than creating new law (Wythe cited Francis Bacon's ''Of the Advancement and Proficiencie of Learning'' as support[4]). Therefore, Sale's gift of the slaves to Alexander and Susanna Saunders was valid, even without a formal writing.

The Fowlers also argued that the slaves were lent rather than gifted, but Wythe said that the burden was on the Fowlers to prove this, which they had not. The court found that the slaves were a gift because Saunders took the slaves into his possession and exercised full dominion over them, so the default assumption is that Sale intended to give the slaves to Saunders. Having so determined the Court required the Fowlers to deliver to Patterson the slaves conveyed by Sale, their children, and the profits generated by those slaves since Sale's death, with the exception of any rights Susanna might have inherited from Alexander.[5]

In the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

The Fowlers appealed Wythe's decision to the Virginia Supreme Court, which said that the facts were not sufficiently developed for a court to be able to decide the merits of the case.[6] The Fowlers bill was a bill quia timet (a bill asking a court to enjoin a probable future harm[7]), but the Fowlers presented no evidence that there was any danger of Patterson actually trying to claim the slaves in Lucy's name. Supreme Court President Edumund Pendleton expressed doubt that Susanna had anything to do with the suit at all, and wondered aloud if the suit was a ploy by William Fowler to claim the slaves for himself.[8]

The Supreme Court ordered the Chancery Court to dismiss the Fowlers' bill, ordered Saunders to pay the Fowlers' court costs at the Supreme Court level, and ordered the Fowlers to pay Saunders's court costs at the Chancery Court level.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery, (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 2d ed. 1852).

- ↑ Ch. 5, 7 Hening 237 (Sept. 1758 Session).

- ↑ Ch. 22, 12 Hening 505 (Oct. 1787 Session).

- ↑ Francis Bacon, ''Of the Advancement and Proficiencie of Learning'' (Oxford: Printed by Leon. Lichfield for Rob. Young & Ed. Forrest, 1640), Book VIII, Ch. III, Aphorism LI.

- ↑ During Wythe's time, a woman's legal identity merged with her husband's upon marriage. William Blackstone and St. George Tucker, Blackstone's with Notes of Reference to the Constitution and Laws of the Federal Government of the United States and of Virginia, (Philadelphia: Wm. Young Birch and Abraham Small, 1803): Vol. 2, p. 441. The editor of the second edition of Wythe's Reports noted that this still left an important question unanswered: exactly where did Lucy's right to the slaves come from? If it came from Sale's will, then Susanna would still have the right to the slaves during Susanna's lifetime. If Lucy's right was inherited through Alexander, then the right to the slaves immediately went to Lucy. Wythe 328, Footnoe *.

- ↑ Fowler v. Saunders, 8 Va. (4 Call) 361 (1798).

- ↑ "quia timet", Black's Law Dictionary (St. Paul, MN: Thomson Reuters, 10th Ed. 2014): 1443.

- ↑ Fowler v. Saunders, 8 Va. at 363.