Ta tou Pindarou Sesosmena

by Pindar

| Ta tou Pindarou Sesosmena | |

|

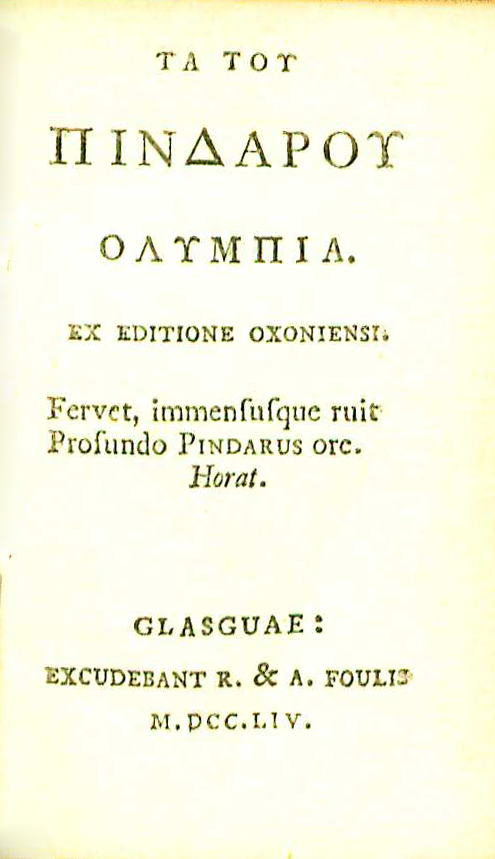

Title page from Ta tou Pindarou Sesosmena, volume one, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Pindar |

| Published | Glasguae: Excudebat R. & A. Foulis |

| Date | 1754-1758 |

| Edition | Ex editione Oxoniensi |

| Language | Greek |

| Volumes | 4 volumes in 3 volume set |

| Desc. | 32mo (8 cm.) |

Pindar (c. 522–443 BCE) was a Greek lyric poet born in Cynoscephalae, Boeotia.[1] He already had panhellenic (across Greece) recognition by the age of 20 when he was commissioned by the rulers of Thessaly, followed by many commissions by ruling and aristocratic families requiring him to travel all over Greece. His ancient reputation is clearly established through the praise of Herodotus and attribution “by many in antiquity as the greatest of the nine poets of the lyric canon.”[2]

Only four of Pindar’s works survive intact and they are contained in this Glasgow edition in the original ancient Greek. Ta tou Pindarou Sesomena: Olympia, Pythia, Nemia, Isthmia are the celebratory choral victory songs composed for the four great panhellenic athletic festivals: the Olympic Games (in Olympia), the Pythian Games (in Delphi – so named for the mythical Python killed by Apollo prior to establishing his oracle and games there), the Nemean Games (in Nemea), and the Isthmian Games (in Corinth – so named for the fact that Corinth is an isthmus).

Athletic competitions were very important to the ancient Greeks, as they provided a measuring ground for the “highest human qualities” of physical fitness and prowess.[3] Pindar’s victory songs, like those of other poets, were sung either immediately after the victory while still at the Games or when the victor went back to his native city. Each victory song consistsof an elaborate announcement of victory, but usually without details beyond the location and specific victorious event. The victor’s associations with any previous victors in his family or his patron are listed, then the song takes a more somber turn by reminding the victor of his mortality and the necessity of divine aid. For this moral component, Pindar often chose myths from the victor’s city and described specific scenes highlighting his moral message and illuminating particular traits of the victor.[4]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Pindar. 3.v. p.f. Foul. Gr." and given by Thomas Jefferson to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The Foulis Press published a four-volume, Greek, trigesimo-segundo (32mo) edition of Pindar between 1754 and 1758. It was the only Greek edition they published.[5] Both George Wythe's Library[6] on LibraryThing and the Brown Bibliography[7] include this edition and note a copy of volume two at the University of Virginia with the inscription "T. J. Randolph" inside the front board which may be Wythe's actual copy (there are no Wythe markings). The Wolf Law Library purchased the same edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

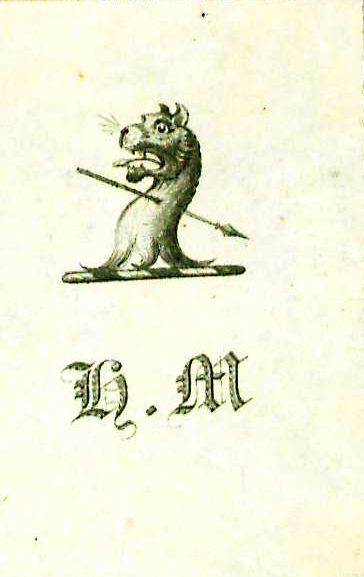

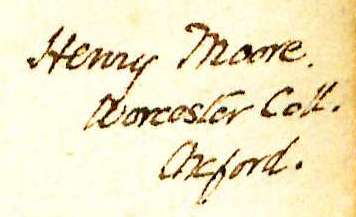

Bound in mottled crimson calf with covers framed in gilt beaded roll. Spines with gilt-stamped title and compartment decorations and board edges with gilt roll. Each front fly-leaf with early inked inscription of Henry Moore, Worcester College, Oxford. Front pastedowns have bookplate of H.M. Purchased from SessaBks.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ "Pindar" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Philip Gaskell, A Bibliography of the Foulis Press, 2nd ed. (Winchester, Hampshire, England: St Paul's Bibliographies, 1986), 190.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on November 14, 2013, http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433