Publii Virgilii Maronis Bucolica, Georgica, et Aeneis

by Virgil

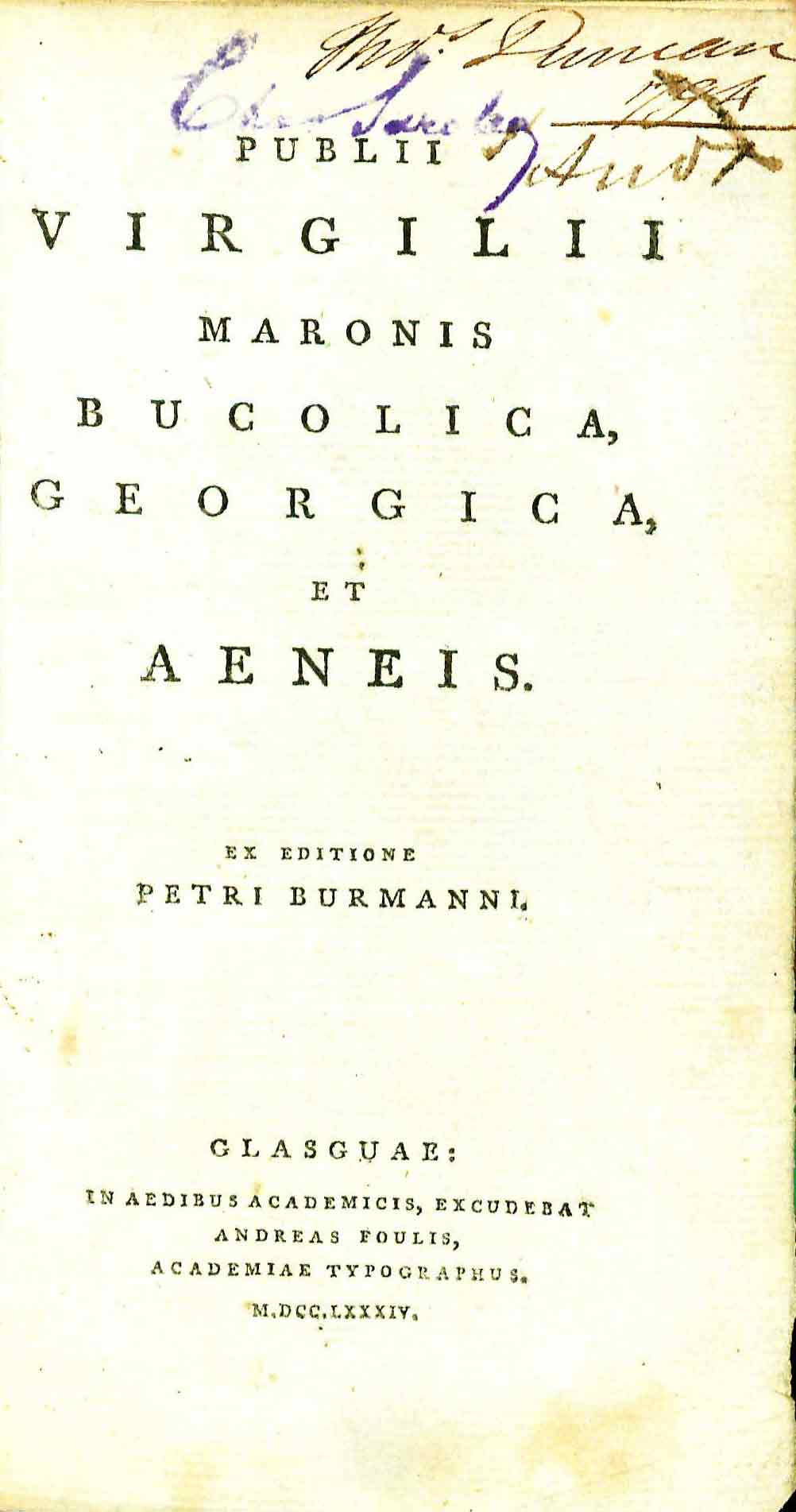

| Publii Virgilii Maronis Bucolica, Georgica, et Aeneis | |

|

Title page from Publii Virgilii Maronis Bucolica, Georgica, et Aeneis, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Virgil |

| Published | Glasguae: In Aedibus Academicis, excudebat Andreas Foulis, Academiae Typographus |

| Date | 1784 |

| Language | Latin |

Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 BCE) was a Roman poet born in Cisalpine Gaul, meaning in Gaul on the side of the Alps closest to Rome (versus Transalpine Gaul). His family was well-off, enabling his studies at Cremona and Milan, as well as Rome and Naples, the latter under the Epicurean philosopher Siro.[1] When land was confiscated following the battle of Phillippi in 42 BCE for the army veterans of Antony and Octavian, Virgil’s family lost land, but he was likely compensated with property near Naples due to his familiarity with the commissioners in charge of distributing that land.[2] Virgil’s Eclogues, his first collection of poems, were likely written around that time, perhaps as late as 38 BCE, due to the confiscations being a central topic of two of the poems.[3] At some later point, Virgil became part of the poetic circle around Maecenas, and therefore was in somewhat close connection with Octavian, the future emperor Augustus. Virgil published his Georgics in 29 BCE. Throughout the 20s BCE, both of Virgil’s books of poetry were widely read and distributed, though they were almost shadowed by his epic poem the Aeneid, which tells the tale of the Trojan Aeneas who flees Troy and eventually founds the Roman civilization.[4] Despite leading a sickly and relatively secretive life, Virgil was extraordinarily famous as the poet who exemplified the greatness of the Roman Empire through “the technical perfection of his verse” and imagery.[5] His fame only grew after his death, with his birthday being celebrated and his works and tomb revered as almost magical or miraculous. His popularity is clear by the vast number, and high quality, of copies of his works that survived from the third to fifth centuries CE. Even Christians, who generally opposed all “pagan” Roman works and ideas, appropriated and interpreted his works to their own benefit and understanding.[6]

This volume contains the three most important of Virgil’s works: the Pastorals (“Bucolics” or “Eclogues”), the Georgics, and the Aeneid. The Pastorals muse on the idyllic life of shepherds in northern Italy, and they range in quality from apt imitations of Greek poems to keen literary and societal prognostication.[7] The Georgics are, similarly, meditations on the nature of agriculture. The name “Georgics” refers to the Greek phrase for “working the land” and the word for “farmer.”[8] Where Virgil’s pastoral poems were largely imitative, the focus and depth of his Georgics were unprecedented.[9] Finally, the Aeneid is Virgil’s great epic, following the tradition of Homer.[10] The work follows the story of Aeneis, who leaves behind his conquered homeland of Troy and goes on to found the culture that will eventually become Rome. Virgil himself captured the scope of these three works with the inscription on his tombstone, “cecini pascua rura duces” (I sang of farms, fields, and heroes).[11]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as [Virgil] Foulis. 12mo. and given by Thomas Jefferson to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The precise edition owned by Wythe is unknown. George Wythe's Library[12] on LibraryThing indicates this, adding "Foulis editions in Latin were published in octavo in 1758 and 1784, and in folio in 1778. Three-volume English editions in duodecimo were published in 1769 and 1775." The Brown Bibliography[13] suggests either the Foulis edition of 1758 or 1784 with a slight preference for the former. The Wolf Law Library purchased the 1784, octavo edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary calf with new backing. Title page includes signatures of former owners "Thos. Duncan, 1794" and "Chas. Saroley."

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ "Virgil” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Virgil " in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007)

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Virgil” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Virgil, Georgics, trans. Peter Fallon, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), xiv.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid, xiii.

- ↑ Virgil, Aeneid, ed. Clyde Pharr, (Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci, 2007), 1–4.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on November 13, 2013, http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433