Demosthenis et Aeschinis Principum Graeciae Oratorum Opera, cum Vtriusque Autoris Vita, et Vlpiani Commentariis

by Demosthenes and Aeschines

| Demosthenis et Aeschinis Opera | ||

|

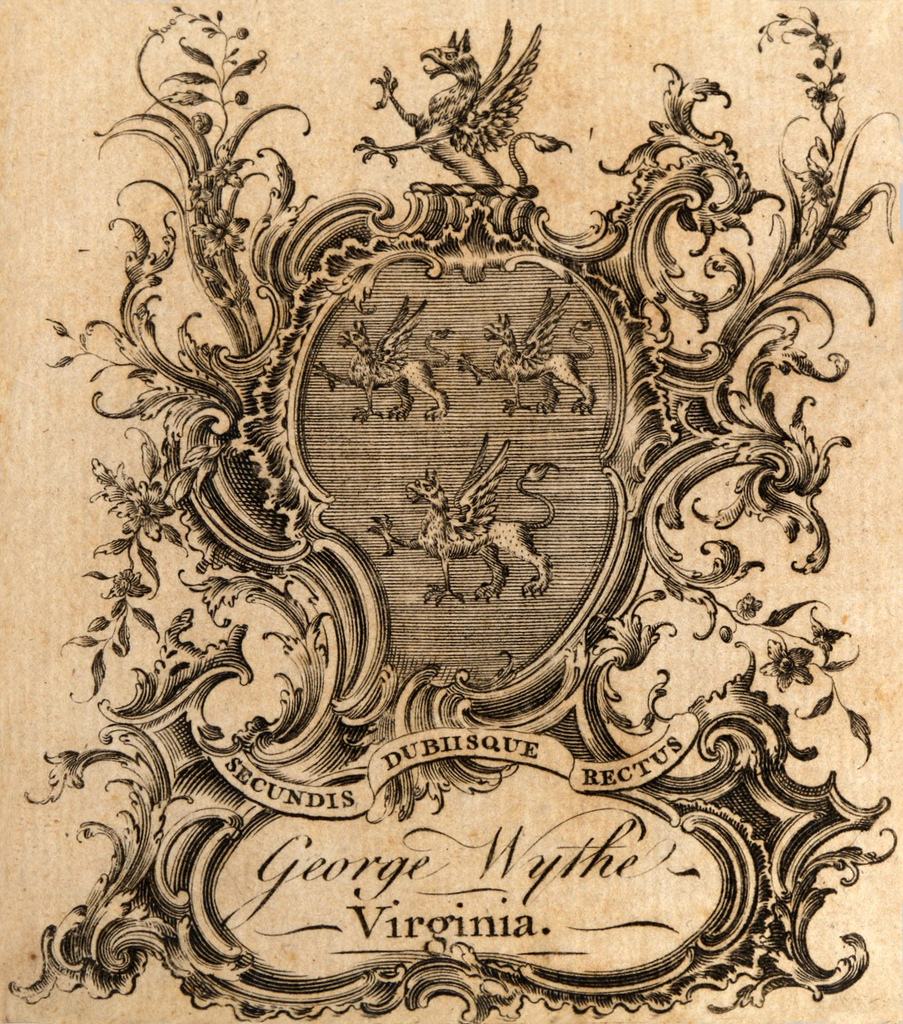

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Demosthenes, Aeschines | |

| Editor | Hieronymus Wolf | |

| Edition | Precise edition unknown | |

| Language | Greek, Latin | |

| Desc. | Folio | |

Demosthenes (384 – 322 BCE) was a prominent statesman and orator in Ancient Greece. He developed his skills as an orator by studying speeches given by earlier great orators.[1] He transferred his talents as an orator and writer into a successful professional speech-writing career. During his time as a speech-writer Demosthenes developed an interest in politics; he went on to devote most of his career to opposing Macedonia's expansion. He spoke out against both Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. Demosthenes played a leading role in his city's uprising against Alexander. The revolt was met with harsh reprisals and Demosthenes took his own life to prevent being arrested. Demosthenes' oratory works were highly influential during the Middle Ages and Renaissance,[2] and inspired the authors of the Federalist Papers and the major orators of the French Revolution.[3]

Aeschines (389 –314 BCE) was a Greek statesman, orator, and bitter political opponent of Demosthenes. He was raised in humble circumstances and worked as an actor before becoming a member of the embassies to Philip II. He eventually provoked Philip II to establish Macedonian control over central Greece. Unlike Demosthenes, Aeschines was a proponent of Macedonian expansion. The two orators collided when Aeschines brought suit against a certain Ctesiphon for proposing the award of a crown to Demosthenes in recognition of his services to Athens. Aeschines suffered a resounding defeat in the trial and subsequently left Athens for Rhodes where he taught rhetoric.[4]

Hieronymus Wolf (1516 – 1580)

In 1572 the publication at Basel of the great edition of Hieronymus Wolf of Augsburg marked a new stage in the study of Demosthenes. Wolf had published a complete Latin translation of the speeches twenty-two years earlier; he now added to this a revised Greek text, and with the Lives and Introductions, together with ancient and modern notes and variant readings, he gave to the student a generous apparatus for Demosthenic studies. In the volume he included the speeches of Aeschines, in Greek and Latin.

The seventeenth century saw no new volumes of the Demosthenic corpus, but we find a score of editions of selected speeches, chiefly the Olynthiacs and Philippics, and the Crown Speech. Nearly all of these were by German and French scholars: none were of great importance, and no noteworthy translations into the modern languages were made. It would seem that the great edition of Wolf, reprinted in 1604, 1607, and 1642, met the needs of the more advanced students throughout the century.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

See also

References

- Jump up ↑ Ian Worthington, Demosthenes: Statesman and Orator (London: Routledge, 2000), 240.

- Jump up ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s.v. "Demosthenes," accessed October 24, 2013.

- Jump up ↑ Konstantinos Tsatsos, "XV" in Demosthenes (Athens: Estia, 1975), 352.

- Jump up ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s.v. "Aeschines," accessed November 14, 2013.

External links

- Read this book in Google Books.