Woodson v. Woodson

Woodson v. Woodson, Wythe 129 (1791),[1] discussed whether a lender is responsible for the profits made off of property held as collateral from the borrower. It is also a good example of how slaves were treated and discussed as property in late-18th-century Virginia.

Background

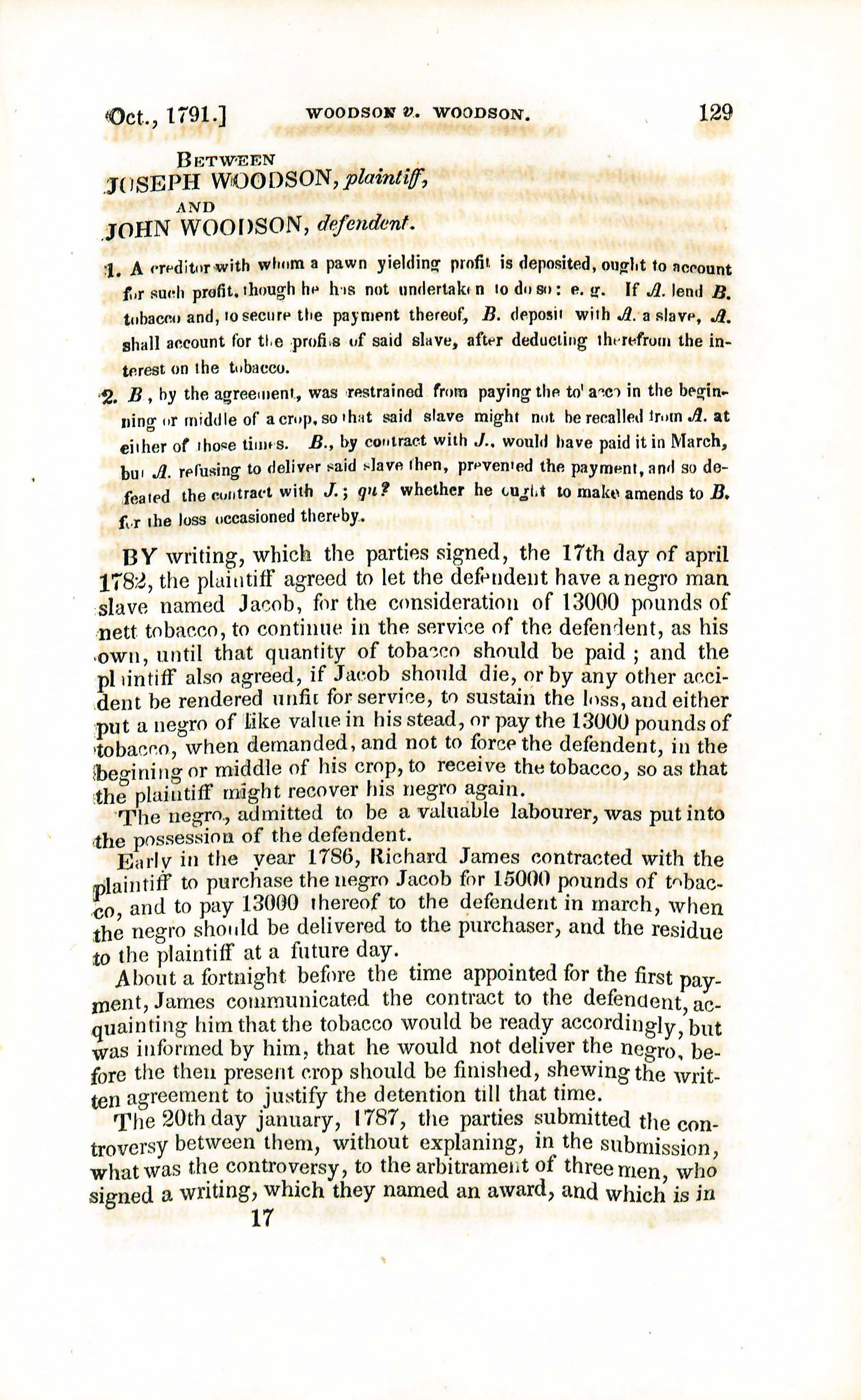

On April 17, 1782, Joseph Woodson pawned his slave, Jacob, to John Woodson for 13,000 pounds of tobacco. Under the Woodsons' pawn agreement, Jacob would work for John until the 13,000 pounds of tobacco were repaid. If Jacob died or was unable to work before Joseph's debt was repaid, then Joseph would absorb the loss and replace Jacob with another slave "of like value" or repay the full debt on demand. Joseph also agreed not to force John to receive full repayment and return Jacob to Joseph at the beginning or in the middle of crop season.

Early in 1786, Richard James bought Jacob from Joseph for 15,000 pounds of tobacco. James would pay 13,000 pounds to John in March, at which time John was to turn Jacob over to James. James would pay the remaining 2,000 pounds to Joseph some time after that.

About two weeks before James was supposed to pay John, James contacted John with the details, and told John that the tobacco payment would be ready as scheduled. John said that he would not turn Jacob over until his crops had been harvested, referring to his contract with Joseph.

On January 20, 1787, the Woodsons and James submitted their dispute to a three-man arbitration panel. The panel said that John should keep Jacob until Joseph paid John 13,000 pounds of tobacco. If Jacob died, then the arbitrators said that Joseph should give John another slave "of equal value".

In January of 1788, Joseph filed a bill in equity with Goochland County Court asking it to order John to apply any profits he made off of Jacob, minus the interest on Joseph's debt, towards the principal on the 13,000-pound loan. John said that Joseph broke their agreement when he refused to turn Jacob over to James. John answered that under their agreement he was not accountable for the profits he made off of Jacob. John also said that James did not offer any tobacco when he asked John to give him Jacob, so John felt that it would not be wise to do so, and the contract did not require it.

The County Court dismissed Joseph's bill and awarded court costs to John. Joseph appealed the decision to the High Court of Chancery.

The Chancery Court's Decision

On October 31, 1791, the Chancery Court reversed the County Court. Wythe ordered John to account for the profits he made off of Jacob. Wythe also ordered John to apply the profits he made off of Jacob first to the interest, then to the principal on his loan to John.

Wythe said that the arbitrators' award should not preclude any relief from the courts because that award just repeated the contract's terms.

Wythe said that allowing John to keep all of the profits from Jacob to apply as John wished (for example, to just pay the interest on his loan to Joseph) would be unjust and would cause much unnecessary waste of resources.[2] If a lender takes the borrower's land as collateral, the lender becomes a trustee for the borrower's land, and is liable to pay the borrower the profits the land makes. Wythe could not find English caselaw on whether the same logic applies when a slave is the collateral, but Justinian's Code says that a lender must apply the profits from the collateral they hold - whether slave, land, or other type of property - to reduce the debt.[3]

Wythe also noted that the Woodsons' agreement did not include a section explaining how interest would be paid. Once Joseph repaid the loan's principal, the contract obligated John to return Jacob, so the only recourse John had for the interest was the profits he made off of Jacob. If John had to account for at least the profits needed to pay the loan's interest, then Wythe reasoned that John should be held accountable for all the profits he made from Jacob, regardless of what John may think.

References

- Jump up ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852): 129.

- Jump up ↑ Wythe uses the phrase ut magis pereat quam valeat. Wythe 130.

- Jump up ↑ Just. Code 4.24.1-4.24.3.