"The Teaching of George Wythe"

Thomas Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," in The History of Legal Education in the United States: Commentaries and Primary Sources, ed. Steve Sheppard (Pasadena, CA: Salem Press, 1999), 1:138-168.[1]

Contents

Chapter 8 text

Page 138

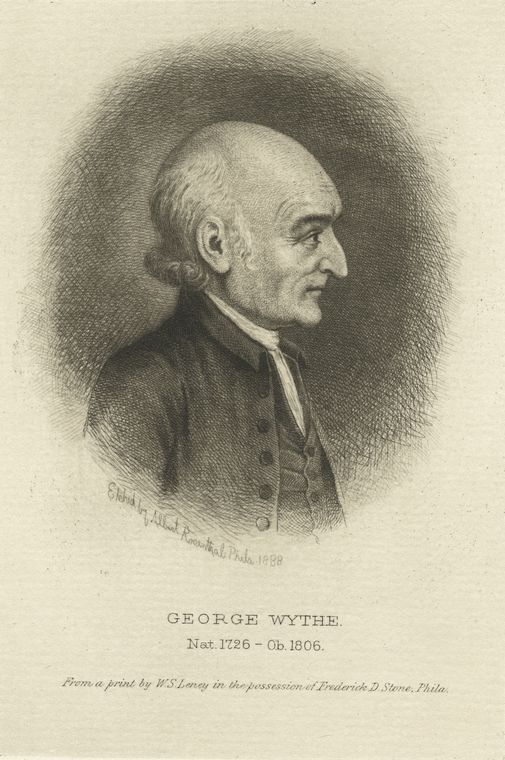

The Teaching of George Wythe

1998

Thomas Hunter

Thomas Hunter is a sometime law professor and a doctoral candidate in history at The Johns Hopkins University.

Author's note: When George Wythe died in 1806, his most famous student, Thomas Jefferson, stated, "He was my antient master, my earliest & best friend; and to him I am indebted for first impressions which have had the most salutary influence on the course of my life."[2] Likewise, nearly half a century later another famous Wythe pupil, Henry Clay, noted that, "to no man was I more indebted, by his instructions, his advice, and his example, for the intellectual improvement which I made, up to ... my twenty-first year."[3]

For many years George Wythe was a major political figure, representing Virginia in the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, serving as Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates, and signing the Declaration of Independence. His judicial career was equally impressive, for he was on Virginia's High Court of Chancery for nearly three decades, including fourteen years as the Commonwealth's sole Chancellor. Such accomplishments, however, while impressive, do little to differentiate Wythe from several of his contemporaries, and his true claim to fame lies not in the law or politics, but as a teacher.

For four decades, Wythe instructed the most promising youth of Virginia in both the law and classics, and in 1779 he became America's first university law professor, and only the second in the English-speaking world, when he was appointed Professor of Law and Police at the College of William and Mary. From Jefferson's entrance into the Continental Congress in 1774 until Clay's resignation from the Senate in late 1851, Wythe's students played crucial roles in the nation's legislative chambers. They were equally important in shaping this nation's jurisprudence, for he taught such noted federal and state jurists as John Marshall, Bushrod Washington, and Spencer Roane. Wythe instructed so well that most of his students assumed leading positions very soon after leaving his counsels, many while still in their twenties.

Despite his role in developing several generations of national leaders, not to mention the high political and judicial stations in which he served, George Wythe has not received the scholarly attention bestowed upon many of his contemporaries or students. It was not until 1970 that the first book-length portrait of

Page 140

Wythe was published, and in the ensuing decades none of the works which have appeared could in any way be termed close to definitive.[4]

Thus, after briefly describing his legal and political career, this essay will examine Wythe's role as Revolutionary Virginia's foremost teacher of both the law and the political process, focusing especially on his seminal ten-year professorship at the College of William and Mary.

* * * * *

George Wythe was born in 1726 or 1727 at his family's home, Chesterville, in Elizabeth City County, Virginia.[5] His parents were Margaret Walker and Thomas Wythe (III), whose grandfather, the first Thomas, emigrated to Virginia in 1680. The first three Thomas Wythes all died quite young, although two lived long enough to serve in the Virginia House of Burgesses.

As for George Wythe's mother, she was the granddaughter of noted teacher, preacher, and controversialist George Keith. The Scottish Keith was "a promising mathematician and student of Oriental languages" before becoming a Quaker and joining the ministry.[6] Coming to America in 1685, Keith was headmaster of a Quaker school until he fell out with the sect because of doctrinal differences. After returning to England, he eventually joined the established church, and in 1702 Keith became the first Anglican missionary sent to America under the auspices of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. It appears that George Wythe inherited both his Christian name and much of his intelligence from his great-grandfather Keith, although he did not have the minister-teacher's "unbearable temper and carriage."[7]

George Wythe was the second of three children, and when his father Thomas (III) died young, an older brother, Thomas (IV), through primogeniture, inherited the family's Chesterville plantation; their other sibling was a sister, Anne, who married Charles Sweeney, and, as is noted below, a grandson of this union, George Wythe Sweeney, perpetrated one of the foulest deeds in Virginia history.

Because he was not in line to inherit the family plantation, it was determined to situate George in one of the professions, with the law being the eventual choice. His earliest schooling, however, was at the hands of his mother, who, because she was raised a Quaker, was unusually educated for a woman of the day. Besides the traditional basics, Margaret Walker Wythe's tutelage of her son included Latin and Greek. At some point Wythe also briefly attended William and Mary, although it is thought that it was only the college's grammar school.[8]

Wythe's professional instruction began in the mid-1740s, when he began an apprenticeship in the Prince George County law office of his uncle Stephen Dewey. As a leading attorney, Dewey's instructions could have proved quite valuable, yet Wythe later told a friend that his uncle "treated him with neglect, and confined him to the drudgeries of his office, with little, or no, attention to his instruction in the general science of law."8[9] One commentator has opined that posterity should maybe thank Dewey for his inattentions, for he may "have sharpened Wythe's appetite for learning in the deeper and richer historical basis of legal institutions, and above all, he seems to have given Wythe a thorough grounding in how not to teach!"[10]

After completing his legal apprenticeship, Wythe received his law license in 1746 and initially settled in Spotsylvania County. There he began a wide-ranging practice which included the counties of Caroline, Orange, and Augusta, and he also became married to attorney Zachary Lewis' daughter Anne. The young Mrs. Wythe died less than a year later, however, and several months after, in October 1748, Wythe returned to the Tidewater region, accepting an offer to become clerk of the two most important committees of the House of Burgesses.

These legislative responsibilities did not preclude the practice of law, so once in Williamsburg Wythe resumed his profession and was soon representing members of such influential Virginia families as the Blairs and Custises. In 1750, the young attorney was elected a Williamsburg Alderman, yet a much higher honor came four years later when he was appointed the colony's Attorney General. Wythe, the youngest attorney general in Virginia history,[11] was chosen to succeed Peyton Randolph, who was visiting England, and he resigned the position once Randolph returned to the colony. While serving as attorney general, another honor came to Wythe when he was elected to the House of Burgesses from Williamsburg.

In 1755, Thomas Wythe (IV) died without an heir and his brother George inherited the Chesterville

Page 141

plantation in Elizabeth City County. It was also at this time that Wythe again married, to Williamsburg heiress Elizabeth Taliaferro, who, being fourteen or fifteen years old, was half of her husband's age. Despite the age difference, theirs was an extremely happy thirty-two year marriage, although their only child died in infancy.

Wythe, who suddenly found himself with his own substantial holdings as well as being married into a wealthy family, could at last "borrow time from his busy professional life for [the] study of the classics and early English literature and law." Such an opportunity was extremely welcomed, for one author has opined that the attorney "thirsted like a living Tantalus for the refreshing springs of the ancient authors."[12] These pursuits had their obvious results, for Thomas Jefferson later called his law teacher "the best Latin and Greek scholar in the State.”[13]

Wythe, while pursuing such academic subjects, did not neglect his professional responsibilities, for he continued his rapid assent [sic] into Virginia's highest legal and political circles. His law practice continued to prosper, and at some early time he became admitted to practice before the colony's highest court, the General Court. The attorneys who practiced before the appellate General Court were a highly select group, usually no more than ten in number, and included such names as Peyton and John Randolph, Robert Carter Nicholas, and Wythe's lifelong rival, Edmund Pendleton. Wythe soon had one of the most notable practices before the court, and Jefferson later noted that Wythe "held without competition the first place at the bar of our general court for 25 years."[14]

As for public service, Wythe lost a race for the House of Burgesses in 1756 when he ran for one of the two seats allotted to his native Elizabeth City County. Two years later, however, he was returned to the House by being elected to the William and Mary seat, for which the electorate was only the college's President and its Masters. In 1761 Wythe received another connection to the college when he was appointed to its Board of Visitors; by this time, however, he was no longer representing the college in the Burgesses, for overcoming his previous defeat he had won election to one of the Elizabeth City County seats.

Wythe was elected Clerk of the House of Burgesses in 1768, a position he would hold for six years, and that year also saw him selected as Mayor of Williamsburg. In addition, his growing influence led to his 1765 appointment to a committee, along with Peyton Randolph, John Randolph, Benjamin Waller, and Robert Nicholas, to collect, edit, and publish the colony's statutes, with the resulting collection being known as the "Code of 1769."

As the Revolution approached, Wythe became known as an ardent rebel, and Jefferson later recalled that "instead of higgling on half-way principle, as others did ... [Wythe] took his stand on the solid ground that the only link of political union between us and Great Britain, was the identity of our Executive; that that nation and its Parliament had no more authority over us, than we had over them."[15] An early example of these feelings came in the 1760s, when Wythe's "remonstrance against the Stamp Act was very bold and strong.”[16] Thus, with such sentiments added to his superb qualifications, it was no surprise when, on August 11, 1775, Wythe, along with Jefferson, Peyton Randolph, Richard Henry Lee, Richard Bland, Benjamin Harrison, and Thomas Nelson, was elected to the Second Continental Congress.

Wythe served in Congress until December 1776, and despite making few speeches he cultivated many friendships and wielded much influence. John Adams was much impressed by Wythe's legal abilities, while Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia thought him "[a] profound lawyer and able politician. He seldom spoke in Congress, but when he did his speeches were sensible, correct and pertinent. I have seldom known a man [to] possess more modesty, or a more dove-like simplicity and gentleness of manner."[17]

By February 1776 Wythe was strongly arguing for independence, yet he did not initially sign the Declaration of Independence in July, for the Virginia delegation had earlier selected Wythe and Richard Henry Lee to travel back to Virginia to attend the convention then drafting a state constitution. The two men left Philadelphia on June 13, yet by the time they arrived in Virginia the drafting, led by George Mason, was well in hand. Wythe, however, was appointed to a small committee to design a state seal, and it is thought that he played a decisive role in choosing the final design.

Wythe returned to Philadelphia in August, and he signed the Declaration in a space his colleagues had specifically left blank in his honor at the top of the delegation's signatures. Wythe remained in Congress

Page 142

until late that fall, returning to Virginia because he, Jefferson, Pendleton, George Mason, and Thomas Ludwell Lee had been appointed to a committee to revise the state's laws. Earlier, there had been several collections of the laws, such as the Code of 1769 produced by Wythe and his colleagues, but this was to be the first thorough revision of all the Commonwealth's statutes. The committee eventually consisted of only three members, Wythe, Jefferson, and Pendleton, and they divided the work such that Jefferson's area of responsibility would be the common law up to 1619, Wythe was to study the British statutes enacted since 1619, and Pendleton was to look at all Virginia-based law.

The work of the revisors was complete in June 1779, when they sent 126 bills to the General Assembly. The legislature, however, dragged its feet in enacting the proposals, and it was only six years later in 1785 that through the efforts of future President James Madison many of the revisors' suggestions were adopted. One reason for this delay might have been that while the majority of the 126 proposed statutes only reiterated the existing law, minus arcane or inappropriate language, under Jefferson's lead the revisors had suggested several profound alterations. Among the suggestions eventually approved were the abolish¬ing of primogeniture, transforming estates in fee tail to fee simple, and establishing religious freedom. Other suggestions equally audacious, however, such as bills promoting public education, a public library, and enlightened penal policies, did not win approval.17

While on the revision committee in 1777, Wythe was chosen as Speaker of the House of Delegates (as it was now termed under the new Constitution). An even greater honor came the following year upon the restructuring of Virginia’s court system, when the General Assembly created three different superior courts which would have appellate jurisdiction in their specialties. A five-member General Court would hear cases at law, while a three-man High Court of Chancery would examine suits in equity, and a Court of Admiralty would make decisions involving maritime law. In addition, the judges of all three courts would, together, form a supreme Court of Appeals.

Of the three separate superior courts, it was considered that the Chancery court, which would meet in April and September, was the most important, and only the foremost attorneys in Virginia were considered in filling the three slots. According to Nathaniel Beverly Tucker, few attorneys of the day had all of the qualifications necessary for the position, for "Integrity and talent were abundant, but a learned lawyer was indeed a rara avis." George Wythe, however, was "the one man in the state who had any claims" to meeting all of these qualifications.18 The members of the General Assembly obviously agreed, for on January 14, 1778, the names of Wythe, Edmund Pendleton, and Robert Carter Nicholas, were placed in nomination for the new court, and they were elected unanimously.

Thus, by the fall of 1779 Wythe was well ensconced on the High Court of Chancery. By filling this high judicial station, however, he could no longer practice law, nor could he serve in the state or national legislature. Thus, it is likely that Wythe was looking for a new challenge, and such was soon offered by his former student Thomas Jefferson.

* * * * *

During his first fifty years, George Wythe did not solely devote himself to politics and the law, for he also gained an enviable reputation as a teacher of young men. Although there likely were earlier students,19 the first known person to study law under Wythe was Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826). After attending William and Mary for two years, Jefferson began his legal apprenticeship in 1762, and he spent three years reading under Wythe's supervision, although the majority of the first year was spent at home in Albemarle county. As was traditional, Jefferson first read Coke on Littleton, and his later readings touched on both the theoretical and practical sides of the law; among the law books he purchased at this time were several volumes on pleading as well as collections of Virginia and British statutes.

Wythe also had Jefferson read widely in the humanities, for the latter purchased and read various works on history, literature, philosophy, religion, and science. As for his routine, shortly after he was admitted to practice Jefferson advised an aspiring lawyer to study such subjects as science, ethics, and religion before breakfast, devote the hours between eight o'clock and noon solely to the law, and then spend the afternoon and evening reading history and literature. While Jefferson could have followed such a rigorous reading schedule while at home, it is known that part of his time in Williamsburg was also spent attending sessions of the General Court and following the legislature; in addition, the young student frequently dined at the

See also

References

- ↑ Thomas Hunter, "The Teaching of George Wythe," in The History of Legal Education in the United States: Commentaries and Primary Sources, ed. Steve Sheppard (Pasadena, CA: Salem Press, 1999), 1:138-168.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to William DuVal, June 14,1806, quoted in Dice Robins Anderson, "The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall," 15 South Atlantic Qtly. 327, 343 (1911). While mispronounced by some, in Virginia the name "Wythe" rhymes with "Smith"; according to one commentator, it is "[p]ronounced 'With' by the cognoscenti for the same reason that they pronounce Coke as 'Cooke'; the linguistic explanation in these cases is perhaps more persuasive than any that might be found for the Virginia practice of pronouncing Talliaferro as 'Tolliver.'" William F. Swindler, "America's First Law Schools: Significance or Chauvinism?," 41 Conn. B.J. 1, 2 n.4 (1967).

- ↑ Henry Clay to Benjamin B. Minor, May 3, 1851, in The Papers of Henry Clay, ed. Robert Seager II et al. (11 vols., 1959-1992), X, 888-89.

- ↑ The four book-length biographies of Wythe are William Clarkin, Serene Paldot: A Life of George Wythe (1970); Joyce Blackburn, George Wythe of Williamsburg (1975); Alonzo Thomas Dill, George Wythe, Teacher of Liberty (1979); Imogene E. Brown, American Aristides: A Biography of George Wythe (1981). Of these, Dill's is by far the best, although it is quite short. Clarkin and Brown include much interesting material, but their works also contain a number of errors and, worst of all, they fail to give citations to much of their information. The best source on Wythe's life up to 1776 remains W. Edwin Hemphill, "George Wythe, the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia" (unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Virginia, 1937). A published dissertation, Robert B. Kirtland, George Wythe: Lawyer; Revolutionary, Judge (1986), contains some useful information. Articles or published speeches on Wythe include Lyon Gardiner Tyler, "George Wythe," in Great American Lawyers, ed. William Draper Lewis (1907), I, 51-90; Oscar L. Shewmake, The Honorable George Wythe: Teacher; Lawyer; Jurist, Statesman (1950); "George Wythe," Dictionary of American Biography, eds. Allen Johnson, Dumas Malone, et al. (1929-1936), XX, 586-89 (hereinafter referred to as DAB); E. Lee Shepard, "George Wythe," in W. Hamilton Bryson, Legal Education in Virginia, 1779-1979: A Biographical Approach, 748-55; Hugh Blair Grigsby, The Virginia Convention of 1776 (1855), 119-30; John Sherman, "George Wythe, the Neglected Patriot: A Bibliography," 34 Bull. Biblio. & Mag. Notes 185 (1977). An excellent source on Wythe's death is The Murder of George Wythe: Two Essays (1955). On Wythe's teaching, see also Anderson, Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall," supra note 1; W. Edwin Hemphill, "George Wythe, America's First Law Professor and Teacher of Jefferson, Marshall, and Clay" (unpublished master's thesis, Emory University, 1933); Paul D. Carrington, "The Revolutionary Idea of University Legal Education," 31 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 527 (1990); Swindler, "America's First Law Schools," supra note 1; Robert M. Hughes, 'William and Mary, the First American Law School," 2 Will. & Mary Qtly., 2d ser., 40 (1922); Fred D. Devitt, Jr., "Note: William and Mary, America's First Law School," 2 Will. & Mary L. Rev. 424 (1960). Oscar Shewmake states that a biography of George Wythe "is not an assignment for a potboiler, ghost-writer or rapid-fire biographer of eminent men ... nor can it be done by some immature doctor of philosophy, suddenly 'come from the nowhere into the here,' who knows only what he had read." Instead, Shewmake writes that the biographer has to be "a Virginian whose ancestors had some part, however small, in the stirring events of the times in which [Wythe] lived." In addition, "he will be one who has himself labored in the several fields in which Wythe wrought so well. He will have been a teacher ... of the type exemplified by Wythe. He will of necessity be a lawyer and, preferably, a member of the judiciary ... [and] will have had experience in legislative work. ... Finally, he will be a man of scholarly attainments witl1 an understanding heart, in short, a gentleman." Shewmake, Honorable George Wythe, at 23-24. It is almost impossible that anyone today could meet all of these qualifications; the late U.S. senator and dean of the William and Mary Law School William B. Spong seems to have satisfied all of the requirements except that he never served on the judiciary. Of course Shewmake's comments are in some respects silly, for in noting the two foremost Virginia biographers of this century, Dumas Malone was neither a lawyer nor a politician (unlike Jefferson), and Douglas Southall Freeman was not a soldier (unlike Robert E. Lee and George Washington).

- ↑ Unless otherwise noted, all information in this subsection, which briefly recounts Wythe's life from 1726 until 1779, comes from Dill, Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, supra note 3, at 3-41.

- ↑ Id. at 4.

- ↑ Tyler, "George Wythe," supra note 3, at 52; Dill, Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, supra note 3, at 5.

- ↑ One source, Shewmake, Honorable George Wythe, supra note 3, at 8, states that Wythe entered William and Mary in 1740 at age fourteen, yet he does not cite to any evidence proving this assertion.

- ↑ Daniel Call, quoted in Dill, Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, supra note 3, at 9.

- ↑ Id. at 9 (emphasis in original).

- ↑ Shewmake, Honorable George Wythe, supra note 3, at 10; Clarkin, Serene Patriot, supra note 3, in the Forward.

- ↑ Dill, Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, supra note 3, at 19.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, "Notes for the Biography of George Wythe," enclosed in Jefferson to John Saunderson, August 31, 1820, in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Andrew A. Lipscomb (1903), I, 167.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Ralph Izard, July 17,1788, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Julian P. Boyd et al. (27 vols. to date, 1950-1997), XIII, 372.

- ↑ Jefferson, "Notes of Wythe," supra note 12, at I, 167-68.

- ↑ Tyler, "George Wythe," supra note 3, at 59.

- ↑ Quoted in Dill, Wythe, Teacher of Liberty, supra note 3, at 30.