Difference between revisions of "Rudiments of the Latin Tongue"

m (→by Thomas Ruddiman) |

m (→by Thomas Ruddiman) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

|desc=[[:Category:Octavos|Octavo]] (17 cm.) | |desc=[[:Category:Octavos|Octavo]] (17 cm.) | ||

|shelf=H-1 | |shelf=H-1 | ||

| − | }}[[wikipedia:Thomas Ruddiman|Thomas Ruddiman]] (1674-1757) was born on the farm of Raggel in the county of Banff, in the parish of Boyndie in October 1674.<ref>George Chalmers, ''The Life of Thomas Ruddiman, A. M.: The Keeper, for Almost Fifty Years, of the Library Belonging to the Faculty of Advocates at Edinburgh'' (London: J. Stockdale, 1794), 2.</ref> His father, a farmer and dedicated monarchist, is believed to have influenced Ruddiman’s work.<ref>Chalmers, ''Life of Thomas Ruddiman'', 3.</ref> He enrolled in Inverboyndie parish school where he displayed a proficiency for classical studies under the tutelage of George Morison.<ref>A. P. Woolrich, "[https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-24249 Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)]," ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', accessed February 5, 2025.</ref> At sixteen, he went to Aberdeen and won an annual bursary competition for classical studies at King’s College.<ref>A. P. Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."</ref> After matriculating in November 1690, Ruddiman received the degree of Artium Magister in June 1694. | + | }}[[wikipedia:Thomas Ruddiman|Thomas Ruddiman]] (1674-1757) was born on the farm of Raggel in the county of Banff, in the parish of Boyndie in October 1674.<ref>George Chalmers, ''The Life of Thomas Ruddiman, A. M.: The Keeper, for Almost Fifty Years, of the Library Belonging to the Faculty of Advocates at Edinburgh'' (London: J. Stockdale, 1794), 2.</ref> His father, a farmer and dedicated monarchist, is believed to have influenced Ruddiman’s work.<ref>Chalmers, ''Life of Thomas Ruddiman'', 3.</ref> He enrolled in Inverboyndie parish school where he displayed a proficiency for classical studies under the tutelage of George Morison.<ref>A. P. Woolrich, "[https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-24249 Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)]," ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', accessed February 5, 2025.</ref> At sixteen, he went to Aberdeen and won an annual bursary competition for classical studies at King’s College.<ref>A. P. Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."</ref> After matriculating in November 1690, Ruddiman received the degree of Artium Magister in June 1694. Working briefly as a tutor to the families of George Ogilvy of Inverquharity and then Robert Young of Auldbar, Forfarshire, Ruddiman was appointed schoolmaster at Laurencekirk, Kincardineshire in 1695.<ref>Douglas Duncan, ''Thomas Ruddiman: A Study in Scottish Scholarship of the Early Eighteenth Century'' (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1965), 2.</ref> There he met Dr. Archibald Pitcairne and received an invitation to Edinburgh under his patronage.<ref>Duncan, ''Thomas Ruddiman'', 2.</ref> With Pitcairne's help, Ruddiman began working as a copyist at the library of the Faculty of Advocates in 1700, rising to "bibliothecar's servant" (assistant librarian) in 1702.<ref>Duncan, ''Thomas Ruddiman'', 3.</ref> |

| − | Ruddiman | + | Ruddiman joined the printing business of Robert Freebairn in 1706 as a proofreader and editor.<ref>Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."</ref> At Freebairn’s suggestion, Ruddiman and his brother Andrew opened their own printing business in 1712, catering mainly to the schoolbooks market.<ref>Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."</ref> After serving as keeper to the Advocates Library' beginning in 1730, Ruddiman retired in 1752 to be succeeded by David Hume.<ref>Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."</ref> He died in Edinburgh on January 19th, 1757 and was laid to rest in Greyfriars churchyard.<ref>Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."</ref> |

His greatest contribution to educational books was ''The Rudiments of the Latin Tongue''. Although the book was first published by Freebairn in 1713, it went through several revisions and established itself as the preeminent Latin grammar book taught in schools across Britain.<ref>Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."</ref> Ruddiman saw ''The Rudiments'' as the “plain and easy instructions, teaching beginners the first principles, or the most common and necessary rules, of Latin.”<ref>Thomas Ruddiman, ''The Rudiments of the Latin Tongue'' (Edinburgh: Murray and Cochran, 1779), 2.</ref> As Ruddiman compiled his text on Latin grammar, he struggled to choose between different pedagogies and ideas about the best possible method to communicate the Latin tongue.<ref>George Chalmers, ''The Life of Thomas Ruddiman'', 64.</ref> In the end, he decided to reduce it into a “short text,” and included an English version alongside the Latin, so readers could choose whichever version suited them better.<ref>Chalmers, ''The Life of Thomas Ruddiman'', 64.</ref> He engaged in thorough research to collect the opinions of the greatest grammatical authorities of the time to inform his work.<ref>Duncan, ''Thomas Ruddiman'', 87.</ref> He believed that the Latin tongue was “designed to be the common Language of learned Men in all the civiliz’d Parts of the World.” | His greatest contribution to educational books was ''The Rudiments of the Latin Tongue''. Although the book was first published by Freebairn in 1713, it went through several revisions and established itself as the preeminent Latin grammar book taught in schools across Britain.<ref>Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."</ref> Ruddiman saw ''The Rudiments'' as the “plain and easy instructions, teaching beginners the first principles, or the most common and necessary rules, of Latin.”<ref>Thomas Ruddiman, ''The Rudiments of the Latin Tongue'' (Edinburgh: Murray and Cochran, 1779), 2.</ref> As Ruddiman compiled his text on Latin grammar, he struggled to choose between different pedagogies and ideas about the best possible method to communicate the Latin tongue.<ref>George Chalmers, ''The Life of Thomas Ruddiman'', 64.</ref> In the end, he decided to reduce it into a “short text,” and included an English version alongside the Latin, so readers could choose whichever version suited them better.<ref>Chalmers, ''The Life of Thomas Ruddiman'', 64.</ref> He engaged in thorough research to collect the opinions of the greatest grammatical authorities of the time to inform his work.<ref>Duncan, ''Thomas Ruddiman'', 87.</ref> He believed that the Latin tongue was “designed to be the common Language of learned Men in all the civiliz’d Parts of the World.” | ||

Revision as of 10:36, 14 May 2025

by Thomas Ruddiman

| Rudiments of the Latin Tongue | |

|

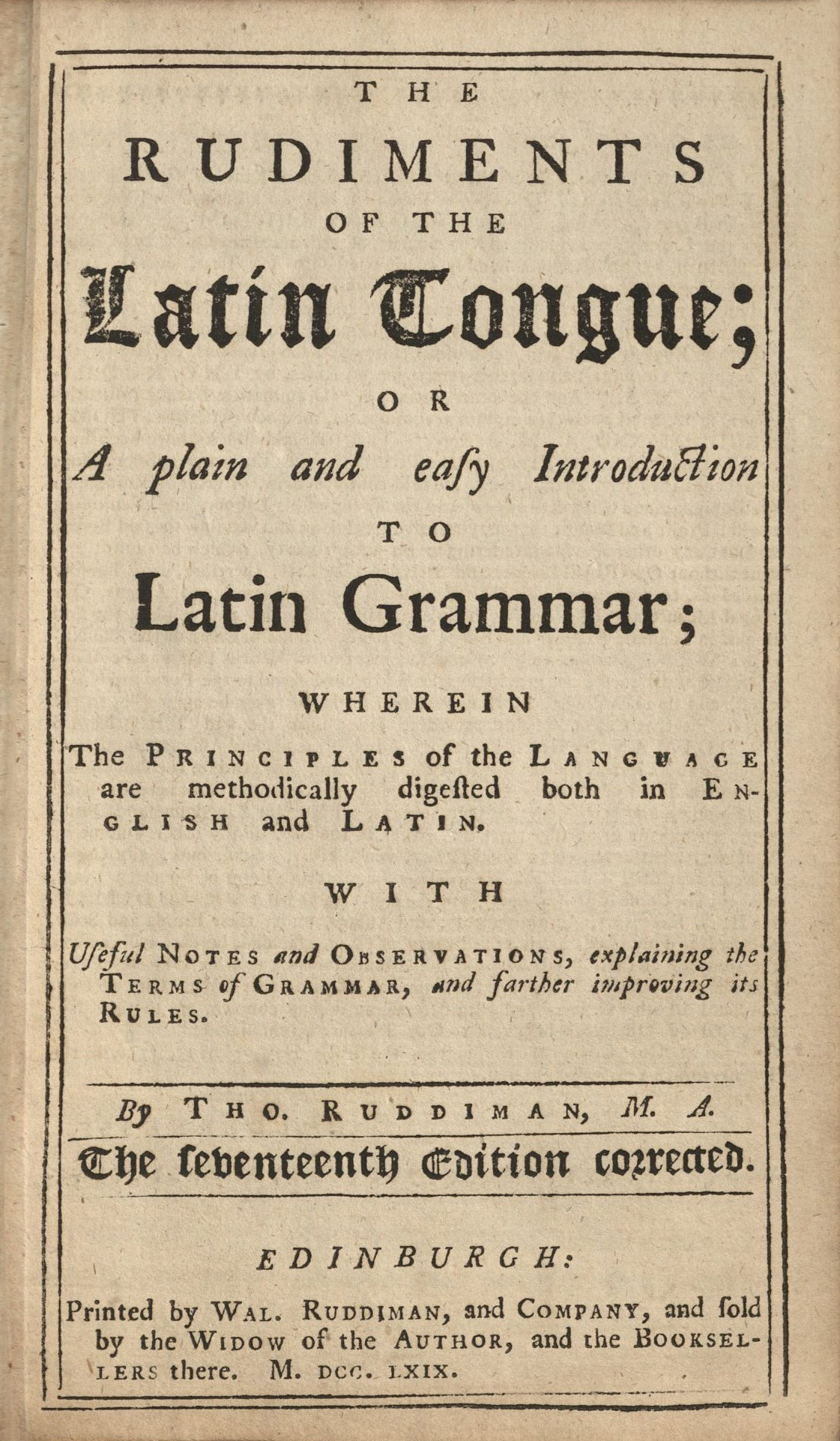

Title page from Rudiments of the Latin Tongue, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Thomas Ruddiman |

| Published | Edinburgh: Printed by Wal. Ruddiman, J. Richardson, and Company and sold by the widow of the author and the booksellers there |

| Date | 1769 |

| Language | Latin |

| Pages | viii, 104, 31, [1] |

| Desc. | Octavo (17 cm.) |

| Location | Shelf H-1 |

Thomas Ruddiman (1674-1757) was born on the farm of Raggel in the county of Banff, in the parish of Boyndie in October 1674.[1] His father, a farmer and dedicated monarchist, is believed to have influenced Ruddiman’s work.[2] He enrolled in Inverboyndie parish school where he displayed a proficiency for classical studies under the tutelage of George Morison.[3] At sixteen, he went to Aberdeen and won an annual bursary competition for classical studies at King’s College.[4] After matriculating in November 1690, Ruddiman received the degree of Artium Magister in June 1694. Working briefly as a tutor to the families of George Ogilvy of Inverquharity and then Robert Young of Auldbar, Forfarshire, Ruddiman was appointed schoolmaster at Laurencekirk, Kincardineshire in 1695.[5] There he met Dr. Archibald Pitcairne and received an invitation to Edinburgh under his patronage.[6] With Pitcairne's help, Ruddiman began working as a copyist at the library of the Faculty of Advocates in 1700, rising to "bibliothecar's servant" (assistant librarian) in 1702.[7]

Ruddiman joined the printing business of Robert Freebairn in 1706 as a proofreader and editor.[8] At Freebairn’s suggestion, Ruddiman and his brother Andrew opened their own printing business in 1712, catering mainly to the schoolbooks market.[9] After serving as keeper to the Advocates Library' beginning in 1730, Ruddiman retired in 1752 to be succeeded by David Hume.[10] He died in Edinburgh on January 19th, 1757 and was laid to rest in Greyfriars churchyard.[11]

His greatest contribution to educational books was The Rudiments of the Latin Tongue. Although the book was first published by Freebairn in 1713, it went through several revisions and established itself as the preeminent Latin grammar book taught in schools across Britain.[12] Ruddiman saw The Rudiments as the “plain and easy instructions, teaching beginners the first principles, or the most common and necessary rules, of Latin.”[13] As Ruddiman compiled his text on Latin grammar, he struggled to choose between different pedagogies and ideas about the best possible method to communicate the Latin tongue.[14] In the end, he decided to reduce it into a “short text,” and included an English version alongside the Latin, so readers could choose whichever version suited them better.[15] He engaged in thorough research to collect the opinions of the greatest grammatical authorities of the time to inform his work.[16] He believed that the Latin tongue was “designed to be the common Language of learned Men in all the civiliz’d Parts of the World.”

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Ruddiman's larger Latin grammar 8vo." Thomas Jefferson gave Wythe's copy to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The precise edition owned by Wythe is unknown. George Wythe's Library[17] on LibraryThing indicates "Precise edition unknown. Numerous octavo editions were published." The Brown Bibliography[18] lists the 1768 edition published in Edinburgh based on the octavo copy Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress in 1815.[19] Since we cannot know which edition Wythe owned, the Wolf Law Library purchased an available copy of the 1769 Edinburgh edition of Rudiments of the Latin Tongue.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary biscuit calf, boards bordered with double gilt rules. Spine features raised bands with gilt rules and blind compartments. Purchased with the George Wythe Boswell-Caracci Room Acquisition Fund.

Images of the library's copy of this book are available on Flickr. View the record for this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

See also

References

- ↑ George Chalmers, The Life of Thomas Ruddiman, A. M.: The Keeper, for Almost Fifty Years, of the Library Belonging to the Faculty of Advocates at Edinburgh (London: J. Stockdale, 1794), 2.

- ↑ Chalmers, Life of Thomas Ruddiman, 3.

- ↑ A. P. Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed February 5, 2025.

- ↑ A. P. Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."

- ↑ Douglas Duncan, Thomas Ruddiman: A Study in Scottish Scholarship of the Early Eighteenth Century (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1965), 2.

- ↑ Duncan, Thomas Ruddiman, 2.

- ↑ Duncan, Thomas Ruddiman, 3.

- ↑ Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."

- ↑ Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."

- ↑ Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."

- ↑ Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."

- ↑ Woolrich, "Ruddiman, Thomas (1674–1757)."

- ↑ Thomas Ruddiman, The Rudiments of the Latin Tongue (Edinburgh: Murray and Cochran, 1779), 2.

- ↑ George Chalmers, The Life of Thomas Ruddiman, 64.

- ↑ Chalmers, The Life of Thomas Ruddiman, 64.

- ↑ Duncan, Thomas Ruddiman, 87.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on June 22, 2015.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012, rev. October, 2023) Microsoft Word file, on file at the Wolf Law Library.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 5:81 [no.4782].