Difference between revisions of "Henrici Mori Cantabrigiensis Opera Omnia"

m |

m (→by Henry More) |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|pages= | |pages= | ||

|desc= | |desc= | ||

| − | }}[[wikipedia: Henry More| Henry More]] (1614-1687) | + | }}Born on October 12, 1614 to an established family of Lincolnshire gentry,<ref>Aharon Lichtenstein, ''Henry More: The Rational Theology of a Cambridge Platonist'' (Harvard University Press, 1962), 3.</ref> [[wikipedia: Henry More| Henry More]] (1614-1687) was a philosopher, poet and theologian who became one of the most prominent members of the [[wikipedia: Cambridge Platonists| Cambridge Platonists]].<ref>Robert Crocker, ''Henry More, 1614-1687: A Biography of the Cambridge Platonist'' (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003), 1.</ref> More studied at the Grammar School at Grantham – later attended by Isaac Newton – then began attending Eton College at age fourteen.<ref>Crocker, ''Henry More, 1614-1687'', 1.</ref> He experienced an early religious crisis at Eton when he started to question his English Calvinist upbringing. This led to a radical reassessment of accepted doctrines and knowledge in terms of their veracity and their spiritual and practical implications.<ref>Crocker, ''Henry More, 1614-1687'', 2.</ref> In 1631, following the path of three elder brothers, More entered [[wikipedia: Christ's_College,_Cambridge|Christ’s College, Cambridge]], where his uncle was a fellow.<ref>Crocker, ''Henry More, 1614-1687'', 1.</ref> He graduated with a Bachelor in Arts in 1636 and a Master of Arts in 1639.<ref>Lichtenstein, ''Henry More'', 7.</ref> Two years later, he was named a Christ’s College fellow and tutor.<ref>Lichtenstein, ''Henry More'', 7.</ref> Despite being ordained as a priest in 1639 and installed as a rector briefly in Ingoldsby, More refused to pursue a clerical career.<ref>Lichtenstein, ''Henry More'', 8.</ref> |

| − | + | More launched his writing career in 1642 with the publication of the philosophical poem, ''Psychodia Platonica'' and followed this with a collection of poems in 1647.<ref>Sarah Hutton, [https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/19181 "More, Henry (1614-1687)"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', accessed September 24, 2024.</ref> In ''An Antidote Against Atheisme'', published in 1653, he produced his first significant apologetic work.<ref>Hutton, "More, Henry (1614-1687)."</ref> More's evolving philosophical and religious view embroiled him in a series of highly public controversies particularly regarding his departure from [[Wikipedia: Calvinism| Calvinism]] to [[wikipedia: Platonism| Platonism]]<ref>Lichtenstein, ''Henry More'', 9.</ref> and his acceptance of [[wikipedia: Origenism| Origenism]].<ref>Hutton, "More, Henry (1614-1687)."</ref> He responded to critics by publishing a lengthy volume, ''The Apology of Dr. Henry More'' in 1664.<ref>Lichtenstein, ''Henry More'', 9.</ref> At this period in his life, he believed that “true, ancient philosophy” consisted of Platonism and [[wikipedia: Cartesianism| Cartesianism]] — the former was the body and the latter, the soul.<ref>Lichtenstein, ''Henry More'', 10.</ref> However, by 1671 More had completely denounced Cartesianism in the ''Enchiridion Metaphysicum,''<ref>Lichtenstein, ''Henry More'', 11.</ref> a work which also solidified "his reputation as a leading philosophical mind of seventeenth-century England."<ref>Hutton, "More, Henry (1614-1687)."</ref> | |

| + | |||

| + | In the 1670’s More was involved in writing the Kabbalah, and translating cabbalistic writings sent to him by Francis Mercury van Helmont. He formed close friendships with Anne Conway, George Rust, Joseph Glanvill, John Worthington and others and collaborated and inspired some of their works and vice versa. The intersection of intellect and will when it comes to religion is the heart of More’s work and his system. More struggled with the debate on transcendence and immanence and found a compromise in the doctrine of anima mundi or “the Spirit of Nature,” which stated that “the world was animated by an unconscious soul which determined the development of the matter within in it, it allowed him to refuse the mere Mechanical aspects of Cartesian thought. More died on September 1, 1687, and was buried in the chapel of Christ’s College. | ||

More’s work Opera Omnia was translated into Latin. It consisted of three volumes and was published in 1979. In his General Preface of his work Opera Omnia, More delineates how his time at Eton led him to shed his Calvinist doctrines and adopt Platonism instead. He discusses how this inaugural step was what led him to embark on a journey of intellectual and spiritual self-discovery. In this auto-biographical section of the book he describes how when he confessed his doubts about Calvinism to members of his family he was threatened with the rod. More theorized that “the end of all ‘true philosophy’ was the defense and explication of Christian religion, and the end of all religion was the believer's ‘Second Birth,’ and his or her illumination or ‘deification.’” His second volume comprises his principal works in Latin and his famous criticisms of Descartes, Spinoza and Boehme. While the translation of his works allowed More’s theories to be received by a wider audience, critics argue that it was just longer prose for his “Spirit of Nature” argument with little amendment. | More’s work Opera Omnia was translated into Latin. It consisted of three volumes and was published in 1979. In his General Preface of his work Opera Omnia, More delineates how his time at Eton led him to shed his Calvinist doctrines and adopt Platonism instead. He discusses how this inaugural step was what led him to embark on a journey of intellectual and spiritual self-discovery. In this auto-biographical section of the book he describes how when he confessed his doubts about Calvinism to members of his family he was threatened with the rod. More theorized that “the end of all ‘true philosophy’ was the defense and explication of Christian religion, and the end of all religion was the believer's ‘Second Birth,’ and his or her illumination or ‘deification.’” His second volume comprises his principal works in Latin and his famous criticisms of Descartes, Spinoza and Boehme. While the translation of his works allowed More’s theories to be received by a wider audience, critics argue that it was just longer prose for his “Spirit of Nature” argument with little amendment. | ||

Revision as of 14:31, 21 January 2025

by Henry More

| Henrici Mori Cantabrigiensis Opera Omnia | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Henry More | |

| Published | Londini: Typis J. Macock, impensis J. Martyn & Gault. Kettilby, sub insignibus Campanae, & Capitis Episcopi in Coemeterio D. Pauli | |

| Date | 1679 | |

Born on October 12, 1614 to an established family of Lincolnshire gentry,[1] Henry More (1614-1687) was a philosopher, poet and theologian who became one of the most prominent members of the Cambridge Platonists.[2] More studied at the Grammar School at Grantham – later attended by Isaac Newton – then began attending Eton College at age fourteen.[3] He experienced an early religious crisis at Eton when he started to question his English Calvinist upbringing. This led to a radical reassessment of accepted doctrines and knowledge in terms of their veracity and their spiritual and practical implications.[4] In 1631, following the path of three elder brothers, More entered Christ’s College, Cambridge, where his uncle was a fellow.[5] He graduated with a Bachelor in Arts in 1636 and a Master of Arts in 1639.[6] Two years later, he was named a Christ’s College fellow and tutor.[7] Despite being ordained as a priest in 1639 and installed as a rector briefly in Ingoldsby, More refused to pursue a clerical career.[8]

More launched his writing career in 1642 with the publication of the philosophical poem, Psychodia Platonica and followed this with a collection of poems in 1647.[9] In An Antidote Against Atheisme, published in 1653, he produced his first significant apologetic work.[10] More's evolving philosophical and religious view embroiled him in a series of highly public controversies particularly regarding his departure from Calvinism to Platonism[11] and his acceptance of Origenism.[12] He responded to critics by publishing a lengthy volume, The Apology of Dr. Henry More in 1664.[13] At this period in his life, he believed that “true, ancient philosophy” consisted of Platonism and Cartesianism — the former was the body and the latter, the soul.[14] However, by 1671 More had completely denounced Cartesianism in the Enchiridion Metaphysicum,[15] a work which also solidified "his reputation as a leading philosophical mind of seventeenth-century England."[16]

In the 1670’s More was involved in writing the Kabbalah, and translating cabbalistic writings sent to him by Francis Mercury van Helmont. He formed close friendships with Anne Conway, George Rust, Joseph Glanvill, John Worthington and others and collaborated and inspired some of their works and vice versa. The intersection of intellect and will when it comes to religion is the heart of More’s work and his system. More struggled with the debate on transcendence and immanence and found a compromise in the doctrine of anima mundi or “the Spirit of Nature,” which stated that “the world was animated by an unconscious soul which determined the development of the matter within in it, it allowed him to refuse the mere Mechanical aspects of Cartesian thought. More died on September 1, 1687, and was buried in the chapel of Christ’s College.

More’s work Opera Omnia was translated into Latin. It consisted of three volumes and was published in 1979. In his General Preface of his work Opera Omnia, More delineates how his time at Eton led him to shed his Calvinist doctrines and adopt Platonism instead. He discusses how this inaugural step was what led him to embark on a journey of intellectual and spiritual self-discovery. In this auto-biographical section of the book he describes how when he confessed his doubts about Calvinism to members of his family he was threatened with the rod. More theorized that “the end of all ‘true philosophy’ was the defense and explication of Christian religion, and the end of all religion was the believer's ‘Second Birth,’ and his or her illumination or ‘deification.’” His second volume comprises his principal works in Latin and his famous criticisms of Descartes, Spinoza and Boehme. While the translation of his works allowed More’s theories to be received by a wider audience, critics argue that it was just longer prose for his “Spirit of Nature” argument with little amendment.

More[17] was a rationalist theologian.[18] He attempted to use the details of 17th-century mechanical philosophy—as developed by René Descartes—to establish the existence of immaterial substance.[19] He was a prolific writer of verse and prose. The Divine Dialogues (1688), a treatise which condenses his general view of philosophy and religion. Like many others he began as a poet and ended as a prose writer. This work was a folio of all of his works, translated into Latin at the urging of a friend as it was believed this would help his works be remembered as classics.[20]

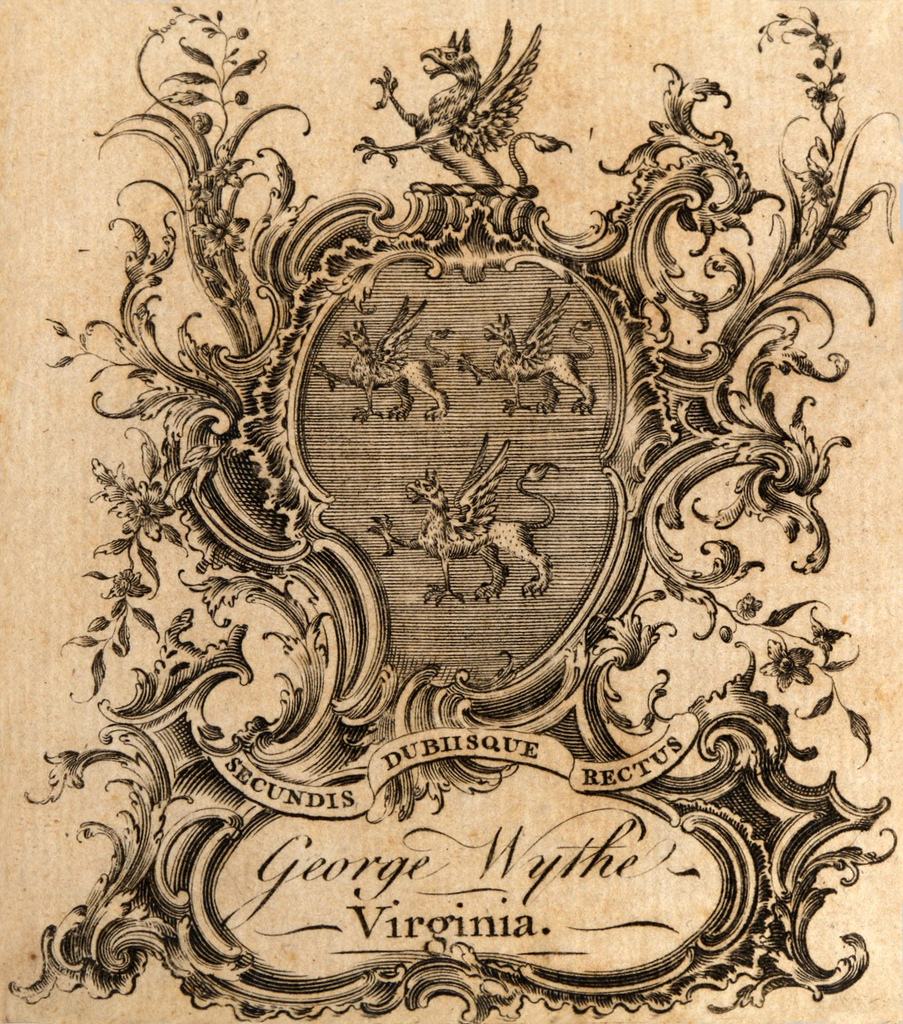

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Mori opera. 2.v. fol." and kept by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson later sold a copy to the Library of Congress in 1815,[21] but the library rebound it, possibly removing any definitive signs of Wythe's previous ownership. However, volume two of this copy does include the inscription "George Walker, Mill Creek, Virginia, 1770" on the title page.[22] Wythe's maternal family owned property near Mill Creek, Virginia[23] and his grandfather, uncle and cousin were named George Walker.[24] Both the Brown Bibliography[25] and George Wythe's Library[26] on LibraryThing list the 1679 edition of this title based on Thomas Jefferson's copy at the Library of Congress. The Wolf Law Library has yet to purchase a copy of More's Opera Omnia.

See also

References

- ↑ Aharon Lichtenstein, Henry More: The Rational Theology of a Cambridge Platonist (Harvard University Press, 1962), 3.

- ↑ Robert Crocker, Henry More, 1614-1687: A Biography of the Cambridge Platonist (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003), 1.

- ↑ Crocker, Henry More, 1614-1687, 1.

- ↑ Crocker, Henry More, 1614-1687, 2.

- ↑ Crocker, Henry More, 1614-1687, 1.

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Henry More, 7.

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Henry More, 7.

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Henry More, 8.

- ↑ Sarah Hutton, "More, Henry (1614-1687)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed September 24, 2024.

- ↑ Hutton, "More, Henry (1614-1687)."

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Henry More, 9.

- ↑ Hutton, "More, Henry (1614-1687)."

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Henry More, 9.

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Henry More, 10.

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Henry More, 11.

- ↑ Hutton, "More, Henry (1614-1687)."

- ↑ Sarah Hutton, "More, Henry (1614-1687)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed September 24, 2024.

- ↑ Henry, John, "Henry More", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 2:124 [no.1532].

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ William Edwin Hemphill, "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia," (PhD diss., University of Virgina, 1937), 16.

- ↑ "George Walker I" in The Mullins Family History Project, accessed September 24, 2024. From the birth/death dates of the three George Walkers, the previous owner was most likely Wythe's uncle George Walker II (died 1773) or cousin Col. George Walker III (died 1800).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, 2024) Microsoft Word file.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on September 24, 2024.