Difference between revisions of "Blackwell v. Wilkinson"

m |

(→Background) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| + | Blackwell v. Wilkinson, Jefferson 73 (1768) involved a dispute over whether an entailment on slaves made before 1727 was valid when the slaves had not been annexed to lands. Wythe, for the defendant, argues that the statute de donis did not make all inheritable real estate entailable.(82). Wythe notes that the statute de donis makes only lands, manors, tenements, and property annexed to lands entailable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | John Randolph, for the plaintiff, | ||

| + | - Legislature declared slaves to be real estate | ||

| + | - Slaves were formerly personal property | ||

| + | - While an act cannot give slaves the physical properties of land, it can give them the legal properties of land. | ||

| + | - The legislature intended to make them real estate – if they had not wanted them to be entailable, then they would have put this language in the law. But they didn’t so we should assume that slaves are entailable like other real property. | ||

| + | - The act of 1727 forbade entailments because the legislature gave too much power to entail with the 1705 act. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wythe: | ||

| + | - Slaves do not fit under the requirements of the statute de donis | ||

| + | - Just because it is real property does not mean that it is entailable – examples: villeins, copyholds | ||

| + | - Wythe argues that the legislature cannot have meant to entail slaves because this would mean the ruin of the heir – he would not be able to sell the slave in order to pay money and he might otherwise have no estate. | ||

| + | - Entails of land have been complained of, but for slaves it is much worse! Slaves are transitory and changeable both in time and place | ||

| + | o Slaves can be conveyed without record/deed | ||

| + | o Entail of slaves can never be docked | ||

| + | o Some slaves will be held in fee simple conditional, others held in tail and will intermix | ||

| + | o This is an attempt to introduce a new perpetuity. | ||

| + | Rebuttal: dignities are entailable becauise of their great honor and importance in the state | ||

| + | Slaves are exercisable in lands and therefore may be entailed | ||

| + | |||

| + | Summary: | ||

| + | This case involved the entailment of slaves between the years 1705 and 1727 and whether an act passed in 1727 prohibiting such entailments applied retroactively to the slaves in this case. | ||

| + | Attorney General John Randolph, for the plaintiff, argued that when the legislature declared slaves to be real estate in 1705, it gave them all of the legal properties of land. According to Randolph, this means that they are entailable in the same way as any other real estate. He further argued that the legislature would have put in language expressly prohibiting entailments if they had intended to not give slaves that quality. Furthermore, the act of 1727 expressly forbade entailments, a law the legislature passed because it recognized that the original act allowed the practice. | ||

| + | Wythe, for the defendant, argued that calling a thing real property does not automatically make the property entailable. He offers copyholds as an example of real property that is not entailable. Wythe argued legislative intent and stated that the legislature did not mean to allow owners to entail slaves because doing so would mean ruin for the heir: he would not be able to sell the slave in order to pay debts and might not have any other estate. Furthermore, Wythe argued, because slaves are transitory and changeable in time and place, can be conveyed without a deed, and an entail of slaves can never be docked, an entailment of slaves would be highly impractical and difficult to apply. | ||

===The Court's Decision=== | ===The Court's Decision=== | ||

| + | The judges ruled 7-3 in favor of the defendant, finding that the entailments were not valid. | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 15:26, 25 May 2023

Introduction and summary.[1]

Background

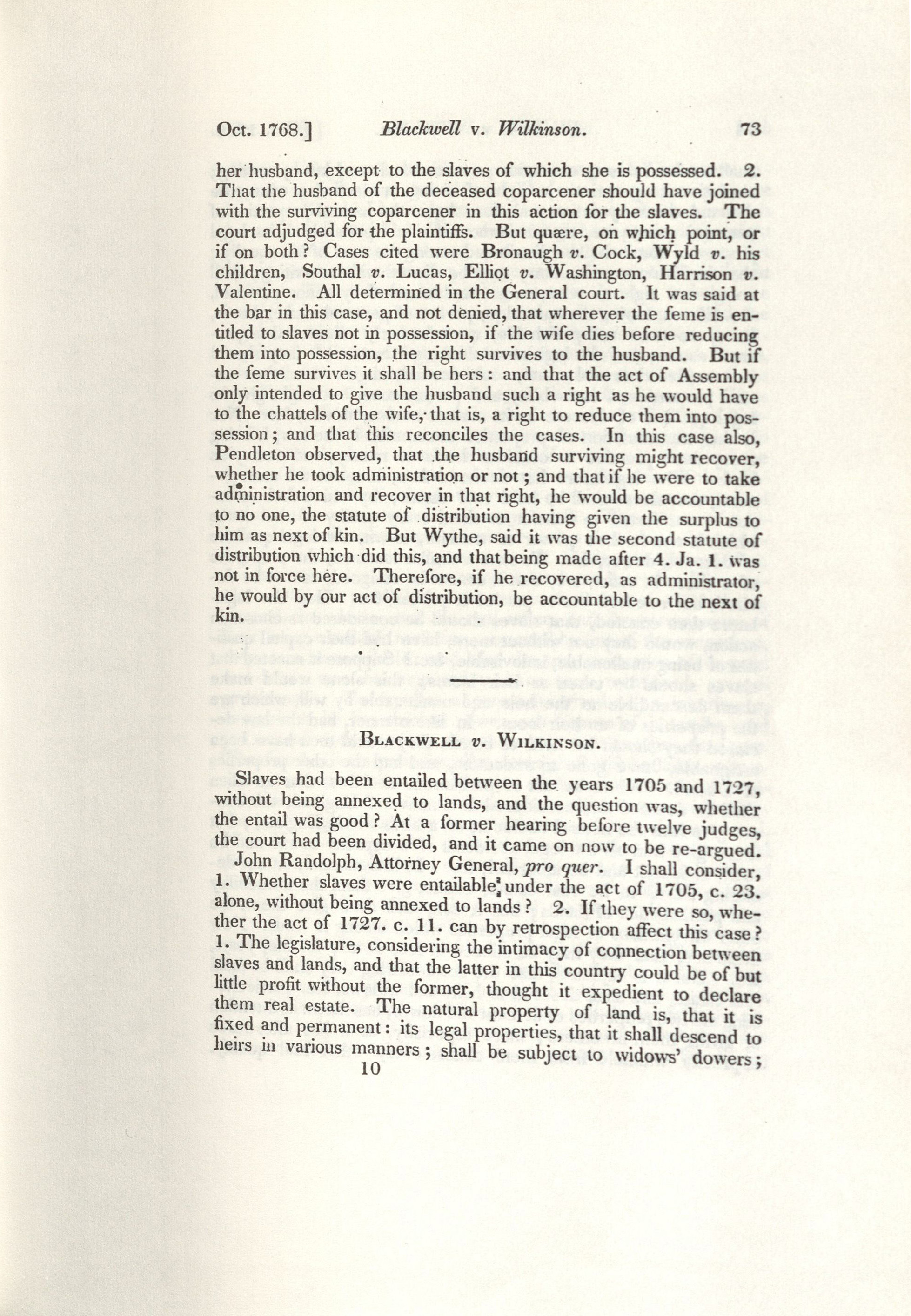

Blackwell v. Wilkinson, Jefferson 73 (1768) involved a dispute over whether an entailment on slaves made before 1727 was valid when the slaves had not been annexed to lands. Wythe, for the defendant, argues that the statute de donis did not make all inheritable real estate entailable.(82). Wythe notes that the statute de donis makes only lands, manors, tenements, and property annexed to lands entailable.

John Randolph, for the plaintiff, - Legislature declared slaves to be real estate - Slaves were formerly personal property - While an act cannot give slaves the physical properties of land, it can give them the legal properties of land. - The legislature intended to make them real estate – if they had not wanted them to be entailable, then they would have put this language in the law. But they didn’t so we should assume that slaves are entailable like other real property. - The act of 1727 forbade entailments because the legislature gave too much power to entail with the 1705 act.

Wythe: - Slaves do not fit under the requirements of the statute de donis - Just because it is real property does not mean that it is entailable – examples: villeins, copyholds - Wythe argues that the legislature cannot have meant to entail slaves because this would mean the ruin of the heir – he would not be able to sell the slave in order to pay money and he might otherwise have no estate. - Entails of land have been complained of, but for slaves it is much worse! Slaves are transitory and changeable both in time and place o Slaves can be conveyed without record/deed o Entail of slaves can never be docked o Some slaves will be held in fee simple conditional, others held in tail and will intermix o This is an attempt to introduce a new perpetuity. Rebuttal: dignities are entailable becauise of their great honor and importance in the state Slaves are exercisable in lands and therefore may be entailed

Summary: This case involved the entailment of slaves between the years 1705 and 1727 and whether an act passed in 1727 prohibiting such entailments applied retroactively to the slaves in this case. Attorney General John Randolph, for the plaintiff, argued that when the legislature declared slaves to be real estate in 1705, it gave them all of the legal properties of land. According to Randolph, this means that they are entailable in the same way as any other real estate. He further argued that the legislature would have put in language expressly prohibiting entailments if they had intended to not give slaves that quality. Furthermore, the act of 1727 expressly forbade entailments, a law the legislature passed because it recognized that the original act allowed the practice. Wythe, for the defendant, argued that calling a thing real property does not automatically make the property entailable. He offers copyholds as an example of real property that is not entailable. Wythe argued legislative intent and stated that the legislature did not mean to allow owners to entail slaves because doing so would mean ruin for the heir: he would not be able to sell the slave in order to pay debts and might not have any other estate. Furthermore, Wythe argued, because slaves are transitory and changeable in time and place, can be conveyed without a deed, and an entail of slaves can never be docked, an entailment of slaves would be highly impractical and difficult to apply.

The Court's Decision

The judges ruled 7-3 in favor of the defendant, finding that the entailments were not valid.

See also

References

- ↑ Please footnote sources.