Difference between revisions of "Strabonis Rerum Geographicarum Libri XVII"

m |

m |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

}}[[File:StrabonisRerumGeographicarum1620InitialCapital.jpg|left|thumb|150px|Headpiece, first page of text.]][http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strabo Strabo] (ca. 64 BCE – ca. 23 CE) was a Greek citizen from a prominent family in Pontus, part of modern Turkey. He traveled extensively, and also lived in Rome where he learned from both political and military leaders.<ref>William A. Koelsch, “Squinting Back at Strabo,” ''Geographical Review'' 94, no. 4 (Oct. 2004): 503.</ref> He wrote a geography of the Greek and Roman world that is almost intact today in seventeen books. This work is Book 17 of those extant. In ancient times, geographies generally took one of two general focuses: the physical geography of an area (the cartography) or “world cultural geography” discussing the impacts of humans on the planet. Strabo’s geography falls into the latter category.<ref>Ibid., 502.</ref><br /> | }}[[File:StrabonisRerumGeographicarum1620InitialCapital.jpg|left|thumb|150px|Headpiece, first page of text.]][http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strabo Strabo] (ca. 64 BCE – ca. 23 CE) was a Greek citizen from a prominent family in Pontus, part of modern Turkey. He traveled extensively, and also lived in Rome where he learned from both political and military leaders.<ref>William A. Koelsch, “Squinting Back at Strabo,” ''Geographical Review'' 94, no. 4 (Oct. 2004): 503.</ref> He wrote a geography of the Greek and Roman world that is almost intact today in seventeen books. This work is Book 17 of those extant. In ancient times, geographies generally took one of two general focuses: the physical geography of an area (the cartography) or “world cultural geography” discussing the impacts of humans on the planet. Strabo’s geography falls into the latter category.<ref>Ibid., 502.</ref><br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | ''On Geography or On Geographical Things'' gained recognition in the mid-fifteenth century when the pope sought to breach the gap between the Eastern and Western Christian churches at an ecumenical council in Florence. Strabo’s ideas were then combined with others, including Ptolemy’s, to help form the scientific foundation for the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Discovery Age of Discoveries and exploration].<ref>Ibid., 504.</ref> Strabo tended to attract the interest of classicists rather than geographers, a shift that relied partly on the belief of some that Strabo’s geographic details are incorrect.<ref>Ibid., 504-505.</ref> | + | ''On Geography'' or ''On Geographical Things'' gained recognition in the mid-fifteenth century when the pope sought to breach the gap between the Eastern and Western Christian churches at an ecumenical council in Florence. Strabo’s ideas were then combined with others, including Ptolemy’s, to help form the scientific foundation for the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Discovery Age of Discoveries and exploration].<ref>Ibid., 504.</ref> Strabo tended to attract the interest of classicists rather than geographers, a shift that relied partly on the belief of some that Strabo’s geographic details are incorrect.<ref>Ibid., 504-505.</ref> |

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 10:13, 10 April 2023

by Strabo

| Rerum Geographicarum | |

|

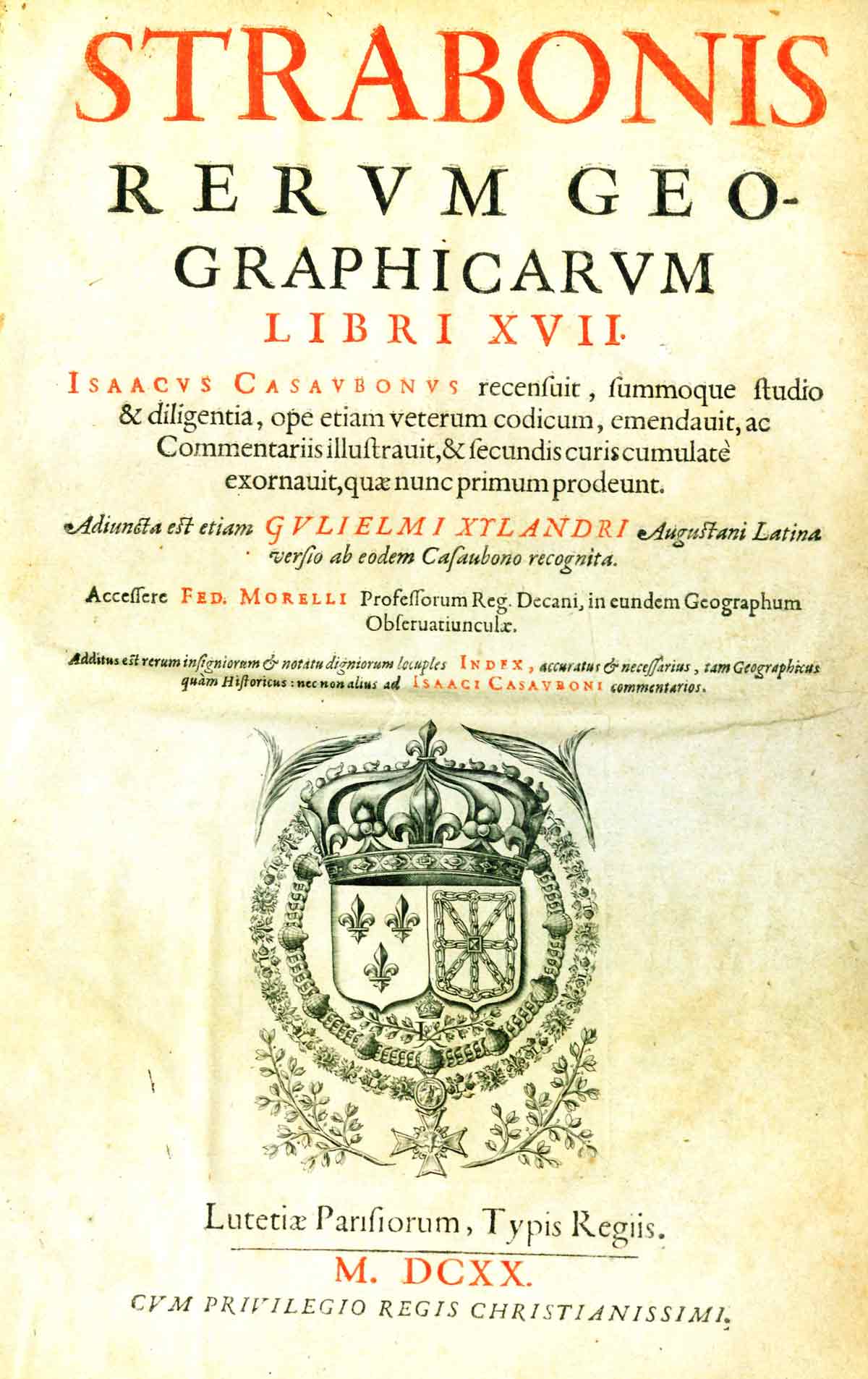

Title page from Rerum Geographicarum, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Strabo |

| Editor | Isaac Casaubon |

| Published | Lutetiae Parisiorum: Typis regiis |

| Date | 1620 |

| Language | Latin and Greek in parallel columns |

| Pages | [12], 843, [116], 282, [8] |

| Desc. | Folio (37 cm.) |

| Location | Shelf B-5 |

On Geography or On Geographical Things gained recognition in the mid-fifteenth century when the pope sought to breach the gap between the Eastern and Western Christian churches at an ecumenical council in Florence. Strabo’s ideas were then combined with others, including Ptolemy’s, to help form the scientific foundation for the Age of Discoveries and exploration.[3] Strabo tended to attract the interest of classicists rather than geographers, a shift that relied partly on the belief of some that Strabo’s geographic details are incorrect.[4]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Strabo. Gr. Lat. fol." and given by Thomas Jefferson to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The precise edition owned by Wythe is unknown. George Wythe's Library[5] on LibraryThing indicates this without selecting a specific edition. The Brown Bibliography[6] lists the 1620 edition published in Paris based on the copy Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress.[7] The Wolf Law Library followed Brown's suggestion and purchased the Paris edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary, recased blind stamped calf. Boards feature elaborate tooling, spine has gilt lettering.

Images of the library's copy of this book are available on Flickr. View the record for this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

See also

References

- ↑ William A. Koelsch, “Squinting Back at Strabo,” Geographical Review 94, no. 4 (Oct. 2004): 503.

- ↑ Ibid., 502.

- ↑ Ibid., 504.

- ↑ Ibid., 504-505.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on November 13, 2013.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 4:86 [no.3820].

External Links

Read this book in Google Books.