Difference between revisions of "M. Tullii Ciceronis Opera quae Supersunt Omnia"

(→Citations from Wythe's Reports) |

m (→Citations from Wythe's Reports) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

''[[Beverley v. Rennolds]]'' | ''[[Beverley v. Rennolds]]'' | ||

| − | Wythe quotes a passage from "Pro Sex. Roscio Amerino | + | Wythe quotes a passage from "Pro Sex. Roscio Amerino" in ''Beverley v. Rennolds'', Wythe 121 (1791),<ref>George Wythe, ''[[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery (1852)|Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions]],'' 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852): 121.</ref> a case discussing whether a court of equity could nullify an arbitrator's award based on a void contract. The quotation appears in Wythe's footnote "(b)" on page 122: |

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

(b) The injury for which Hipkins demanded reparation was that Beverley endeavoured to escape the ruin which the art of Hipkins was contriving. those, who could approve such a demand, perhaps would have thought the demand of Fimbria plausible, who having wounded Scaevola, whom he intended to slay, and finding the wound not mortal, cited him, after he recovered to appear before the judges, and being required to state the cause of his complaint against Scaevola, answered <span style="color: #006600;">''quod non totum telum corpore recepisset''</span>. Cic. ora. pro S. Roscio Amer.<ref>Translation: "because he did not receive the whole weapon into his body." </ref> </blockquote> | (b) The injury for which Hipkins demanded reparation was that Beverley endeavoured to escape the ruin which the art of Hipkins was contriving. those, who could approve such a demand, perhaps would have thought the demand of Fimbria plausible, who having wounded Scaevola, whom he intended to slay, and finding the wound not mortal, cited him, after he recovered to appear before the judges, and being required to state the cause of his complaint against Scaevola, answered <span style="color: #006600;">''quod non totum telum corpore recepisset''</span>. Cic. ora. pro S. Roscio Amer.<ref>Translation: "because he did not receive the whole weapon into his body." </ref> </blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 14:38, 5 April 2018

by Marcus Tullius Cicero

| M. Tullii Ciceronis Opera quae Supersunt Omnia | |

|

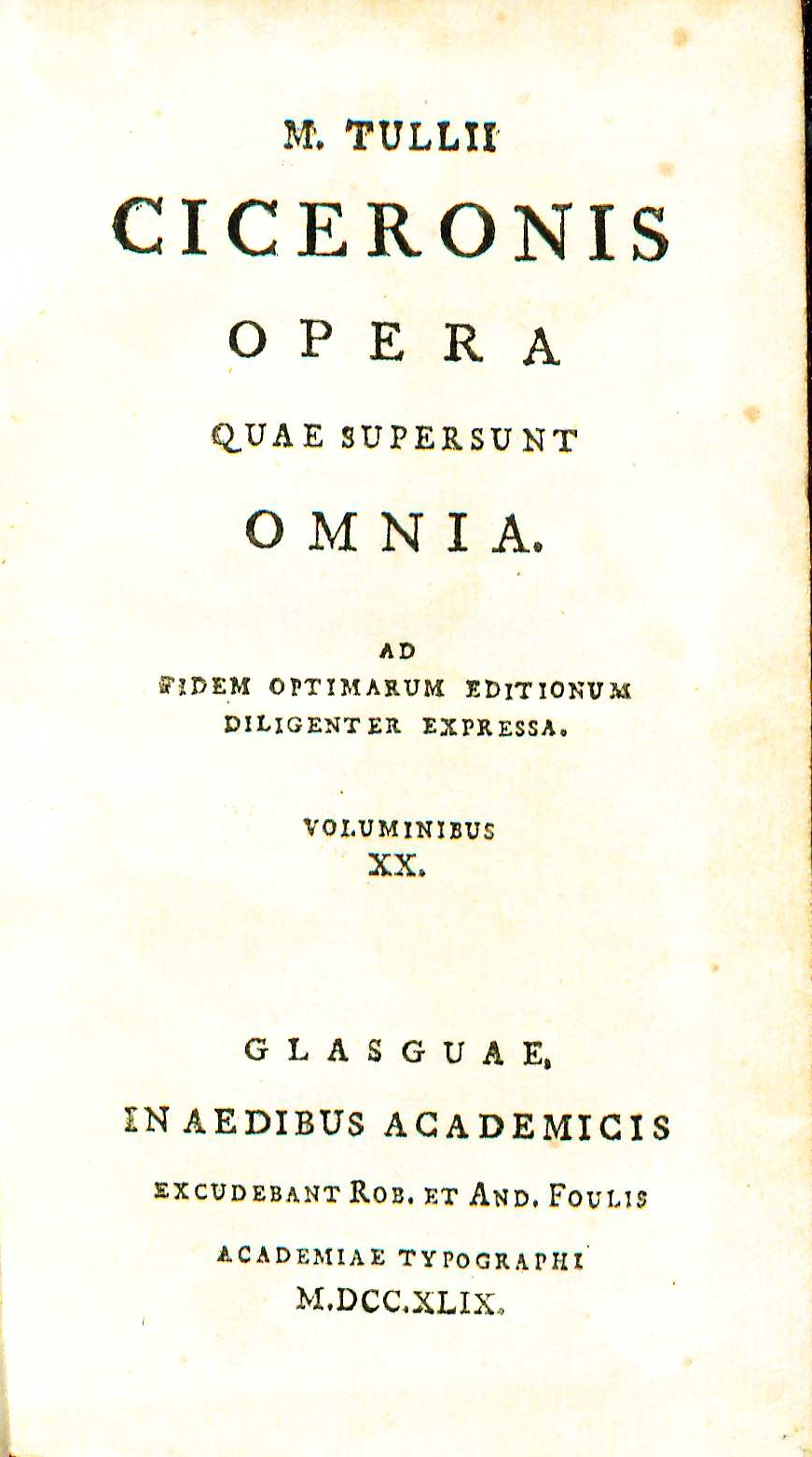

Title page from M. Tullii Ciceronis Opera quae Supersunt Omnia, volume one, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Marcus Tullius Cicero |

| Editor | George Rosse, Pierre-Joseph Thoulier, abbe d' Olivet, Zachary Pearce |

| Published | Glasguae: In Aedibus Academicis, Excudebant Rob. et And. Foulis |

| Date | 1748-1749 |

| Edition | First Foulis |

| Language | Latin |

| Volumes | 20 volume set |

| Desc. | 12mo (14 cm.) |

| Location | Shelf J-2 |

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 BCE-43 BCE) was a Roman statesman, politician, orator and writer.[1] He distinguished himself in the practice of law before entering politics and winning a consulship in 63 BCE.[2] As head of the Senate, Cicero thwarted the Catilinarian conspiracy to seize control of the government and struggled to uphold republican ideals amidst the civil wars that destroyed the Roman Republic.[3] Caesar’s rise to power ended Cicero's political career, and he devoted himself to writing, producing such works as Consolatio, Hortensius, De Natura Deorum' and the Tusculan Disputations.[4] He was executed at the behest of Mark Antony, whom Cicero had criticized publicly when Octavian rose to power.[5]

Cicero is considered the foremost Roman orator. His style, which became known as Ciceronian rhetoric, was the primary rhetorical model for centuries.[6] Among his greatest works are his Catilinarian orations, the Phillipics delivered against Mark Antony, and his political works De Legibus, De Re Publica and De Oratore.[7] Cicero’s primary contribution to philosophy was bringing Greek ideas into Latin, allowing Rome to develop its own philosophical traditions.[8] He had a lasting impact on Renaissance and early modern thinkers, including Locke, Montesquieu and Hume.[9] Cicero’s conception of rationally-discernible natural law influenced America’s founders, including John Adams, James Wilson, and Thomas Jefferson.[10] Jefferson explicitly named him as helping establish a notion of “public right” that influenced the Declaration of Independence and the Revolution.[11]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as Ciceronis opera. Lat. 20.v. 16[mo?]. Foulis and given by Thomas Jefferson to his son-in-law and nephew, John Wayles Eppes. The 1748-1749 edition is the only 20 volume Latin edition published by Foulis. Both Brown's Bibliography[12] and George Wythe's Library[13] on LibraryThing include this edition and the Wolf Law Library purchased the same set.

Citations from Wythe's Reports

Wythe quotes a passage from "Pro Sex. Roscio Amerino" in Beverley v. Rennolds, Wythe 121 (1791),[14] a case discussing whether a court of equity could nullify an arbitrator's award based on a void contract. The quotation appears in Wythe's footnote "(b)" on page 122:

(b) The injury for which Hipkins demanded reparation was that Beverley endeavoured to escape the ruin which the art of Hipkins was contriving. those, who could approve such a demand, perhaps would have thought the demand of Fimbria plausible, who having wounded Scaevola, whom he intended to slay, and finding the wound not mortal, cited him, after he recovered to appear before the judges, and being required to state the cause of his complaint against Scaevola, answered quod non totum telum corpore recepisset. Cic. ora. pro S. Roscio Amer.[15]

Wythe owned two Latin sets of Cicero's works: this title, M. Tullii Ciceronis Opera quae Supersunt Omnia andM. Tullii Ciceronis Opera cum Delectu Commentariorum. Both sets include "Pro Sex. Roscio Amerino."[16]

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary full polished calf with speckled edges. Each volume includes the signature of previous owner "? Kenneary(?)" on the front pastedown. Volume fourteen's inscription is inverted on the rear pastedown. Purchased from Rose's Books.

Images of the library's copy of this book are available on Flickr. View the record for this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

See also

- George Wythe Room

- Jefferson Inventory

- M.T. Ciceronis Orationes Quaedam Selectae

- M. Tullii Ciceronis Opera cum Delectu Commentariorum

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, s.v. "Cicero, Marcus Tullius," accessed October 9, 2013.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Classical Philosophy, s.v. ""CICERO, Marcus Tullius (106-43 B.C.E.)," accessed October 9, 2013.

- ↑ Philip's Encyclopedia, s.v. "Cicero, Marcus Tullius," accessed October 9, 2013.

- ↑ Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, s. v. "Cicero, Marcus Tullius."

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Classical Philosophy, s. v. "CICERO, Marcus Tullius (106-43 B.C.E.)."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Walter Nicgorski, ""Cicero and the Natural Law," Natural Law, Natural Rights and American Constitutionalism (National Endowment for the Humanities, n.d.), accessed Oct. 9, 2013.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on October 9, 2013.

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852): 121.

- ↑ Translation: "because he did not receive the whole weapon into his body."

- ↑ in M. Tullii Ciceronis Opera quae Supersunt Omnia, volume 4, pages 57-141, and in M. Tullii Ciceronis Opera cum Delectu Commentariorum], volume IV, pages 62-111.

External Links

Read volume eighteen of this title in Google Books.