Difference between revisions of "Essay Concerning Humane Understanding"

(→Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding''}} | ||

===by John Locke=== | ===by John Locke=== | ||

| − | |||

{{NoBookInfoBox | {{NoBookInfoBox | ||

|shorttitle=An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding | |shorttitle=An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding | ||

| Line 17: | Line 16: | ||

|pages=[38], 438 (i. e. 432), [12] | |pages=[38], 438 (i. e. 432), [12] | ||

|desc=Folio (33 cm.) | |desc=Folio (33 cm.) | ||

| − | }} | + | }}Born into a family of means but minor status in Wrighton, Somerset, [[wikipedia:John Locke|John Locke]] (1632–1704) would become a philosopher and political theorist whose works would influence and shape the Enlightenment in Europe. |

| − | Born into a family of means but minor status in Wrighton, Somerset, [[wikipedia:John Locke|John Locke]] (1632–1704) would become a philosopher and political theorist whose works would influence and shape the Enlightenment in Europe. | ||

| − | Locke's father was a country attorney and a steward to a powerful local family who sponsored the younger Locke's early education, beginning in 1647 in London. In 1652, Locke moved on to university at [wikipedia:Christ Church, Oxford|], studying alongside the likes of [[wikipedia:John Dryden|John Dryden]], [[wikipedia:Robert Hooke|Robert Hooke]], and [[wikipedia:Christopher Wren|Christopher Wren]]. Locke took both a Bachelors and Masters of Arts, in 1656 and 1658. | + | Locke's father was a country attorney and a steward to a powerful local family who sponsored the younger Locke's early education, beginning in 1647 in London. In 1652, Locke moved on to university at [[wikipedia:Christ Church, Oxford|Christ Church]], studying alongside the likes of [[wikipedia:John Dryden|John Dryden]], [[wikipedia:Robert Hooke|Robert Hooke]], and [[wikipedia:Christopher Wren|Christopher Wren]]. Locke took both a Bachelors and Masters of Arts, in 1656 and 1658. |

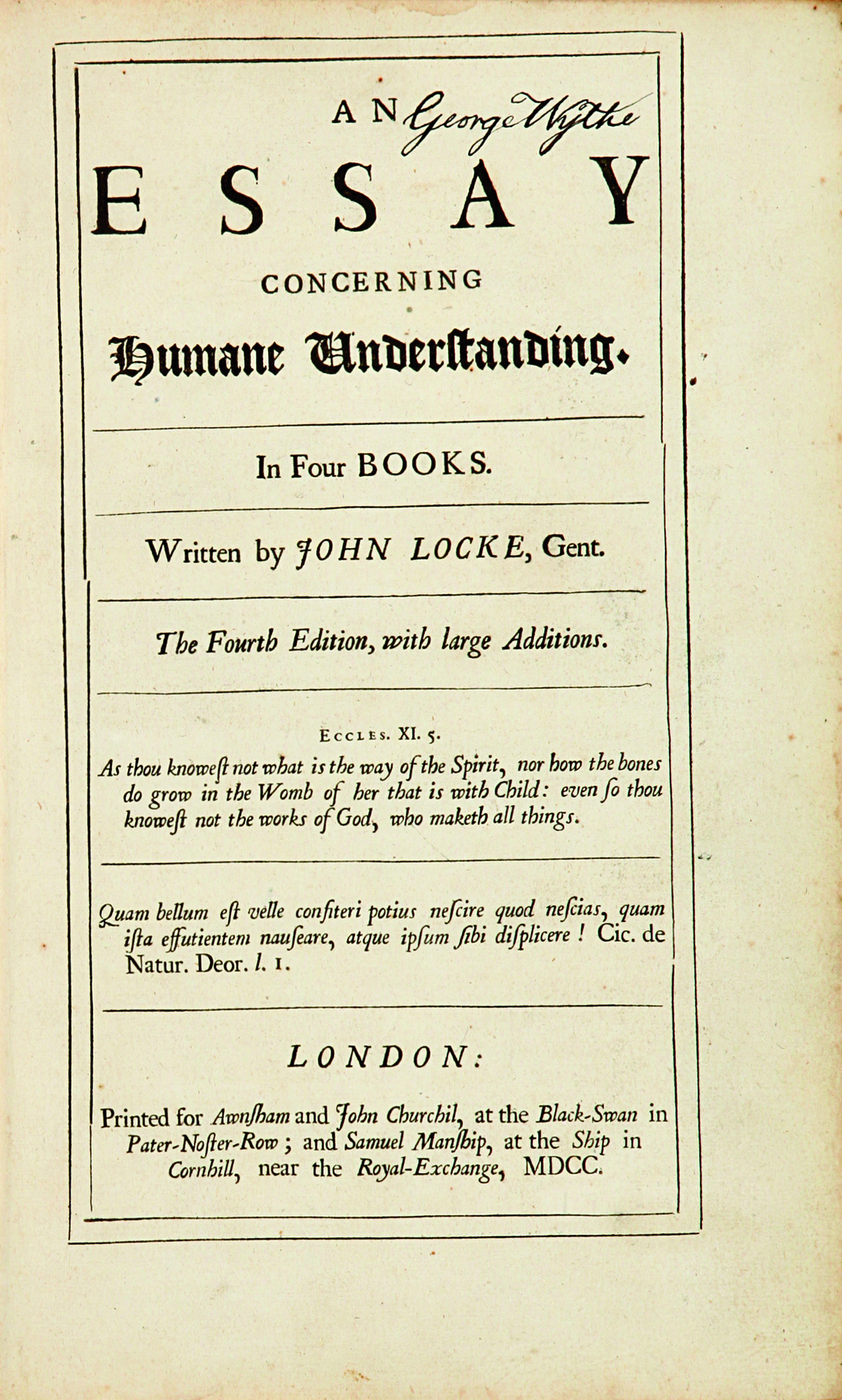

[[File:LockeEssayConcerningHumaneUnderstanding1700TitlePage.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Title page from [[George Wythe|George Wythe's]] personal copy of ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding'' (London: Printed for Awnsham and John Churchil ... and Samuel Manship, 1700). Wythe's copy is in a private collection.]] | [[File:LockeEssayConcerningHumaneUnderstanding1700TitlePage.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Title page from [[George Wythe|George Wythe's]] personal copy of ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding'' (London: Printed for Awnsham and John Churchil ... and Samuel Manship, 1700). Wythe's copy is in a private collection.]] | ||

| Line 172: | Line 170: | ||

[[Category:Philosophy]] | [[Category:Philosophy]] | ||

[[Category:Titles in Wythe's Library]] | [[Category:Titles in Wythe's Library]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | __NOTOC__ | ||

Revision as of 10:00, 19 March 2016

by John Locke

| An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | John Locke | |

| Published | London: Printed for Awnsham and John Churchil ... and Samuel Manship | |

| Date | 1700 | |

| Edition | Fourth | |

| Language | English | |

| Pages | [38], 438 (i. e. 432), [12] | |

| Desc. | Folio (33 cm.) | |

Born into a family of means but minor status in Wrighton, Somerset, John Locke (1632–1704) would become a philosopher and political theorist whose works would influence and shape the Enlightenment in Europe.

Locke's father was a country attorney and a steward to a powerful local family who sponsored the younger Locke's early education, beginning in 1647 in London. In 1652, Locke moved on to university at Christ Church, studying alongside the likes of John Dryden, Robert Hooke, and Christopher Wren. Locke took both a Bachelors and Masters of Arts, in 1656 and 1658.

In 1666 Locke met and befriended Anthony Ashley Cooper, the first Earl of Shaftesbury. In 1675, Locke took a Bachelor's of medicine at Christ Church, allowing him to occupy a medical studentship at the college. Shaftesbury appointed Locke as his personal physician, and remained Locke's patron for more than two decades. In 1679, when Shaftesbury's bid to bar the Catholic duke of York (later, King James II) from the royal succession failed, the two went into exile in the Netherlands, returning in 1688 when William III, a Protestant, was placed on the throne.[1]

Locke's most significant works were published after his return to England. In 1690, he published his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which he had begun while in exile. Locke's Essay was born of a lively conversation with a number of associates and friends, after which he wrote some "hasty and undigested thoughts" on the ultimate subject of the work. Dedicated to Thomas Herbert, the Earl of Pembroke, the Essay explores "the discerning faculties of man" with respect to the world around him. Locke advocated in this work an exploration of the world in such a manner where sensation and perception dictate what attributes the explorer attributes to the object. In other words, Locke's work discouraged the attribution of innate, but imperceptible, qualities to objects, instead advocating attributing only perceptible qualities to items. Such an approach is reminiscent of his disapproving views on the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (where the substance of the Eucharist is in fact changed into the body or blood of Christ, even though all outward appearances would indicate no change to the bread or wine).[2]

The Essay is notable for a key example it uses: the substance known in contemporary England as "manna". In Locke's time, there were several connotations to the word. The first, and perhaps most well-known today, is the idea of it as the miraculous bread dropped on the wandering Israelites. The second relates to the quasi-agricultural product of the same name, derived from the Southern European flowering ash tree. The sap of the tree, which acts as a laxative, was used frequently by Europeans at that time.

The crux of Locke's manna example was to instill in his reader the idea that the sensations that one associates with a certain item are not qualities that the item itself possesses. Indeed, the gastric pains brought about by eating the substance, according to Locke, were human responses to the substance, and not qualities that the substance itself possessed. In a similar vein, Locke describes the other qualities of manna: its white color, its sweetness, and its texture. Again, Locke claims that these are correct perceptions of the "operations" of the substance. The fact that people ascribe the sensations imposed upon them to the substance itself, Locke theorized, was an incorrect way of thinking, focusing upon misperception of reality rather than reality itself. A correct manner of thought would be to observe the qualities an item displays absent human interjection of values, relying instead on what the observer could physically sense.

Numerous scholars postulate that Locke's manna example serves as a stand-in for the Eucharist used in Christian worship. Locke opposed the Catholic doctrine of "substance and accidents" wherein observers could only perceive the "accident" of some item, but not the "substance". In other words, humanity could witness the outward qualities of an item (shape, texture, etc.) but could not perceive the true essence of any given item. This doctrine founded the basis for transubstantiation in the Church: while all outward appearances of the wafer indicate that it is bread, the essence of it changed into Christ's literal flesh.[3] Locke, in the Essay, opposed this idea. The very heart of his argument was that observers should not project human experience upon an object, instead resting solely on what was observable. Locke's Essay serves as a guide regarding proper methods of thought regarding objects, and as a criticism of a rival theology.[4]

Locke's essays are widely considered his seminal work for their analysis of human methods of thought and as criticisms of rival doctrines. Written while in exile from England, Locke's work quickly took hold in a number of intellectual circles around Europe, and had a lasting impact upon the time’s conception of natural philosophy and of the nature of religious doctrine and political power.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

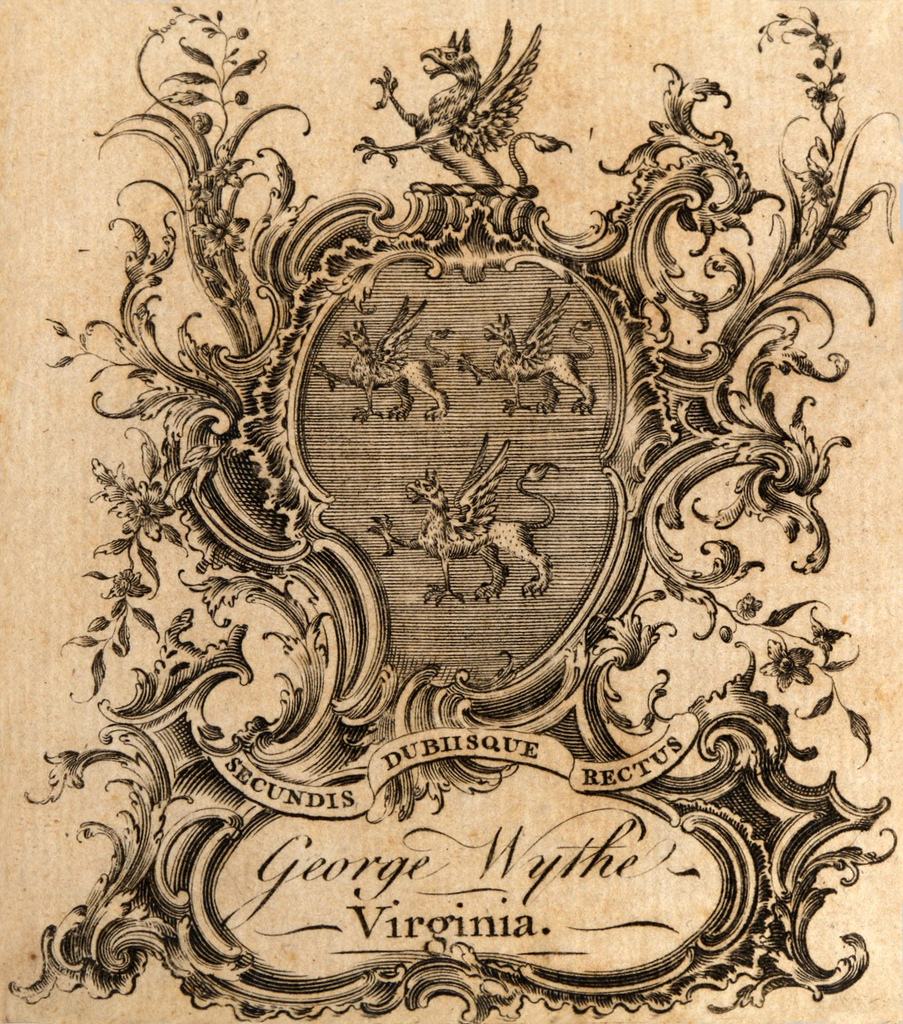

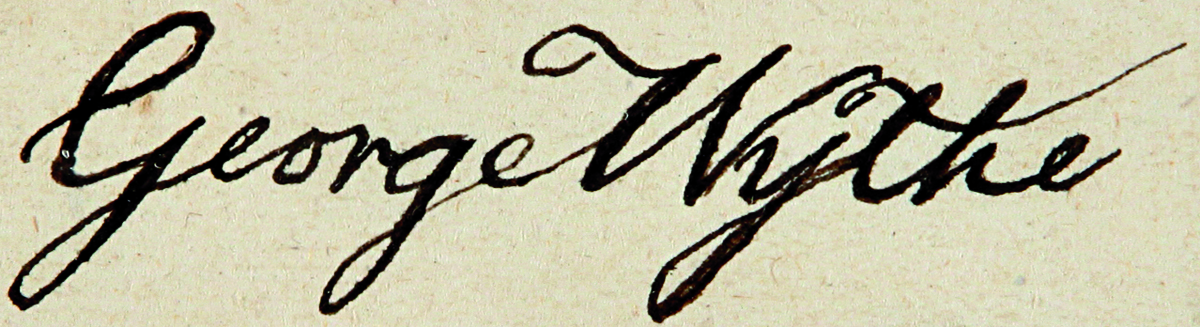

George Wythe's copy of this book has survived, and is currently in a private collection. The title page boasts a clear, bold version of Wythe's signature in the top right corner.

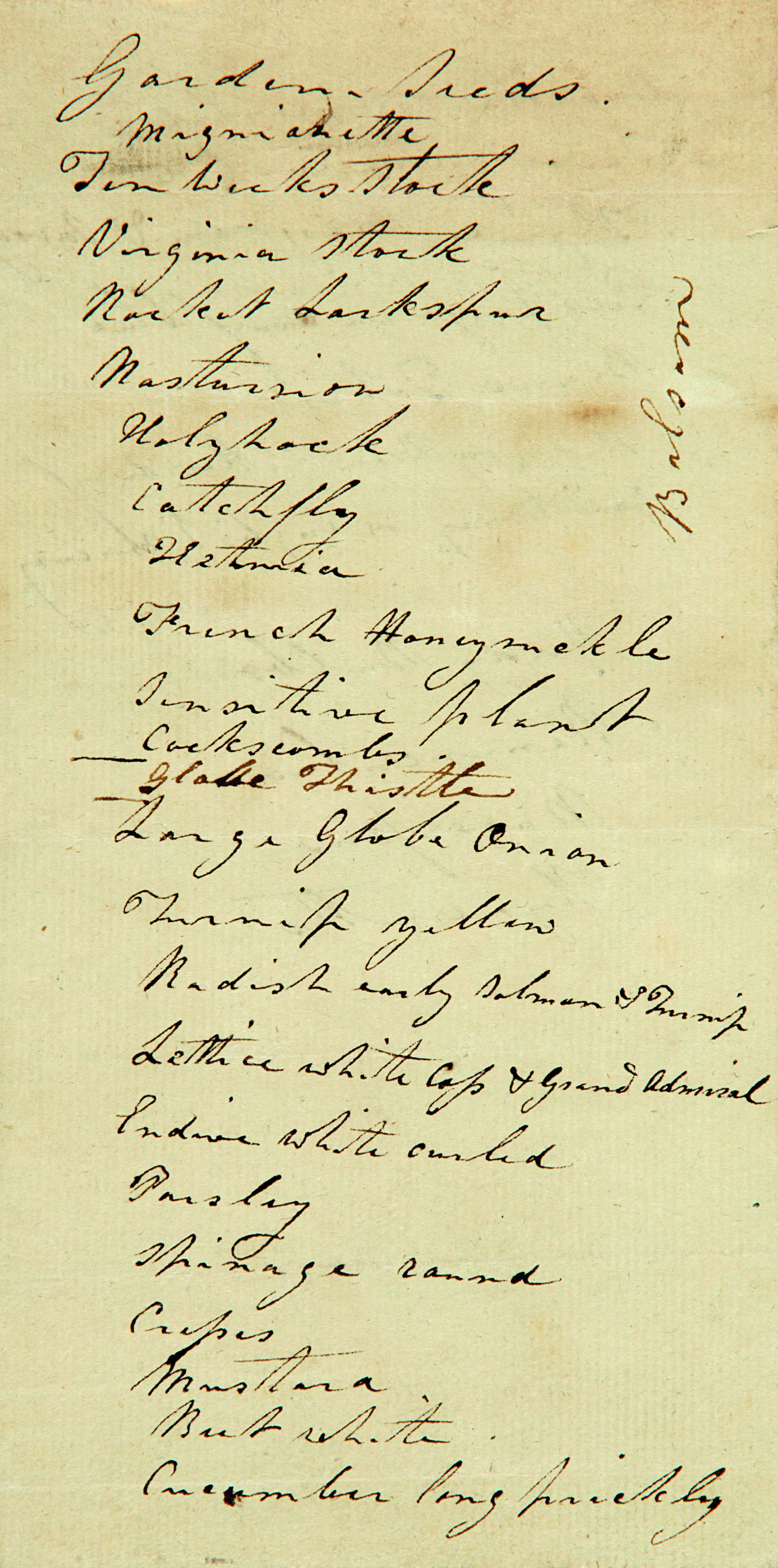

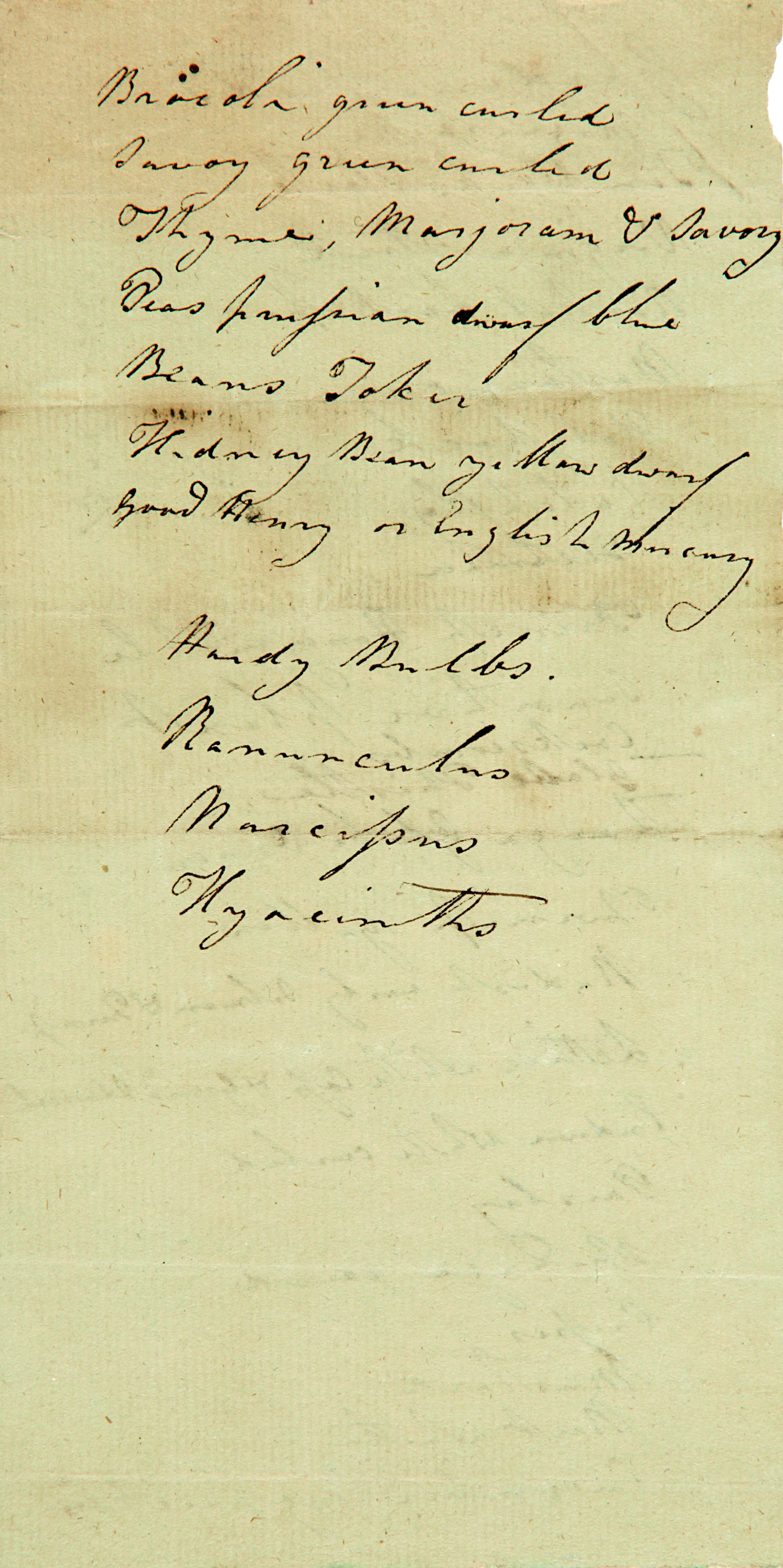

Found inserted between the pages of the book was a list of "Garden Seeds" and "Hardy Bulbs" in Wythe's handwriting, presumably intended for filling his garden with flowering plants, and vegetables and herbs. A cookbook Wythe purchased in 1764, The Art of Cookery, uses many of these products as ingredients:

|

A list of seeds and bulbs (front) found in George Wythe's personal copy of An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. Wythe's copy is in a private collection. |

|

A list of seeds and bulbs (back) found in George Wythe's personal copy of An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. Wythe's copy is in a private collection. |

See also

References

- ↑ J. R. Milton, "Locke, John (1632–1704)," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church," Vatican Archives, accessed April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Catechism."

- ↑ Olivia Smith, "Thinking Through Things in Texts: A Seventeenth-Century Example," Paragraph, 37, no. 1 (1998), 112-25.

External links

- Read this book in Google Books.