Difference between revisions of "Reports de Sr. Creswell Levinz"

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|pages= | |pages= | ||

|desc=Folio | |desc=Folio | ||

| − | }}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creswell_Levinz Sir Creswell Levinz] (1627–1701) was a judge, the second son of William Levinz and Mary Creswell. Born in Evenley, Levinz became in 1648 a sizar, or research fellow, at Trinity College, Cambridge, but never graduated. He entered [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gray%27s_Inn Gray's Inn] in November 1655 and was called to the bar in November 1661. On October 2, 1678, Levinz was knighted and on October 25 he was appointed king's counsel. The latter position led him to represent the crown in the famous [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popish_Plot Popish Plot] trials of 1678–1679. On October 27, 1679, Levinz was appointed attorney general. The following year, he married Elizabeth Livesay.<ref>D. E. C. Yale, "[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16555 Levinz, Sir Creswell (1627–1701),]" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed February 16, 2015.</ref><br /> | + | }}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creswell_Levinz Sir Creswell Levinz] (1627–1701) was a judge, the second son of William Levinz and Mary Creswell. Born in Evenley, Levinz became in 1648 a sizar, or research fellow, at Trinity College, Cambridge, but never graduated. He entered [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gray%27s_Inn Gray's Inn] in November 1655 and was called to the bar in November 1661. On October 2, 1678, Levinz was knighted, and on October 25 he was appointed king's counsel. The latter position led him to represent the crown in the famous [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popish_Plot Popish Plot] trials of 1678–1679. On October 27, 1679, Levinz was appointed attorney general. The following year, he married Elizabeth Livesay.<ref>D. E. C. Yale, "[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16555 Levinz, Sir Creswell (1627–1701),]" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed February 16, 2015.</ref><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | On February 12, 1681, Levinz was appointed as a judge in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_of_Common_Pleas_(England) Court of Common Pleas] and | + | On February 12, 1681, Levinz was appointed as a judge in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_of_Common_Pleas_(England) Court of Common Pleas] and appointed sergeant-at-law. On February 9, 1686, he was dismissed from his position on the court "because, too inflexible in the cause of independence and right, he had resolutely opposed the King's [James II] dispensing power."<ref>John William Wallace, ''The Reporters, Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks'', 4th ed., rev. and enl. (Boston: Soule and Bugbee, 1882), 306.</ref> After the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glorious_Revolution Glorious Revolution of 1688], he was returned to the bar. Levins stopped practicing law in 1696. He died at Serjeants' Inn on January 29, 1701, and was buried at Evenley, where a monument to him and his standing effigy in robes are located.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | Levinz' ''Reports'' was published in 1702 as a folio volume in three parts | + | Levinz' ''Reports'' was published in 1702 as a folio volume in three parts. It was republished in 1722 in two volumes when it was translated from Law French into English.<ref>Ibid.</ref> The cases listed in the ''Reports'' were cases decided en banc in the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_of_King%27s_Bench_%28England%29 Court of King's Bench], from 1660 through 1696. The first part of the ''Reports'' contains cases from 1660 through 1671 under the Chief Justiceships of Sir Robert Foster, Sir Robert Hide, and Sir John Keeling. The second part includes cases from 1671 through 1681 under the Chief Justiceships of Sir Matthew Hale, Sir Richard Rainsford, and Sir William Scroggs. The final part contains cases cases through 1696, from the remainder of Levinz' time practicing law.<br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

The ''Reports'' gained a mixed reputation. One justice described a reported opinion as "so absurd ... [one] can lay no weight on it;" yet, the book was cited often and described as "of authority."<ref>Wallace, ''The Reporters, Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks'', 305.</ref> After Levinz' death, Lord Philip York, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, stated that Levinz was "a good lawyer, [but] he was sometimes a very careless reporter."<ref>Edward Foss, ''Biographia Juridica: A Biographical Dictionary of the Judges of England from the Conquest to the Present Time, 1066-1870'', (London: John Murray, 1870), 406-407.</ref> Although the ''Reports'' received adverse criticism<ref>Ibid.</ref> from the legal community of the time, there is no evidence that Levinz intended his private collection of reports and records to be published.<ref>Yale, "Levinz, Sir Creswell (1627–1701)."</ref> | The ''Reports'' gained a mixed reputation. One justice described a reported opinion as "so absurd ... [one] can lay no weight on it;" yet, the book was cited often and described as "of authority."<ref>Wallace, ''The Reporters, Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks'', 305.</ref> After Levinz' death, Lord Philip York, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, stated that Levinz was "a good lawyer, [but] he was sometimes a very careless reporter."<ref>Edward Foss, ''Biographia Juridica: A Biographical Dictionary of the Judges of England from the Conquest to the Present Time, 1066-1870'', (London: John Murray, 1870), 406-407.</ref> Although the ''Reports'' received adverse criticism<ref>Ibid.</ref> from the legal community of the time, there is no evidence that Levinz intended his private collection of reports and records to be published.<ref>Yale, "Levinz, Sir Creswell (1627–1701)."</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:44, 11 May 2015

by Sir Creswell Levinz

| Levinz's Reports | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Sir Creswell Levinz | |

| Published | London: Printed by the assigns of Richard and Edward Atkins esq; for S. Keble ... D. Browne ... T. Benskin ... and J. Walthoe | |

| Date | 1702 | |

| Language | French | |

| Volumes | 2 volume set | |

| Desc. | Folio | |

Sir Creswell Levinz (1627–1701) was a judge, the second son of William Levinz and Mary Creswell. Born in Evenley, Levinz became in 1648 a sizar, or research fellow, at Trinity College, Cambridge, but never graduated. He entered Gray's Inn in November 1655 and was called to the bar in November 1661. On October 2, 1678, Levinz was knighted, and on October 25 he was appointed king's counsel. The latter position led him to represent the crown in the famous Popish Plot trials of 1678–1679. On October 27, 1679, Levinz was appointed attorney general. The following year, he married Elizabeth Livesay.[1]

On February 12, 1681, Levinz was appointed as a judge in the Court of Common Pleas and appointed sergeant-at-law. On February 9, 1686, he was dismissed from his position on the court "because, too inflexible in the cause of independence and right, he had resolutely opposed the King's [James II] dispensing power."[2] After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, he was returned to the bar. Levins stopped practicing law in 1696. He died at Serjeants' Inn on January 29, 1701, and was buried at Evenley, where a monument to him and his standing effigy in robes are located.[3]

Levinz' Reports was published in 1702 as a folio volume in three parts. It was republished in 1722 in two volumes when it was translated from Law French into English.[4] The cases listed in the Reports were cases decided en banc in the Court of King's Bench, from 1660 through 1696. The first part of the Reports contains cases from 1660 through 1671 under the Chief Justiceships of Sir Robert Foster, Sir Robert Hide, and Sir John Keeling. The second part includes cases from 1671 through 1681 under the Chief Justiceships of Sir Matthew Hale, Sir Richard Rainsford, and Sir William Scroggs. The final part contains cases cases through 1696, from the remainder of Levinz' time practicing law.

The Reports gained a mixed reputation. One justice described a reported opinion as "so absurd ... [one] can lay no weight on it;" yet, the book was cited often and described as "of authority."[5] After Levinz' death, Lord Philip York, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, stated that Levinz was "a good lawyer, [but] he was sometimes a very careless reporter."[6] Although the Reports received adverse criticism[7] from the legal community of the time, there is no evidence that Levinz intended his private collection of reports and records to be published.[8]

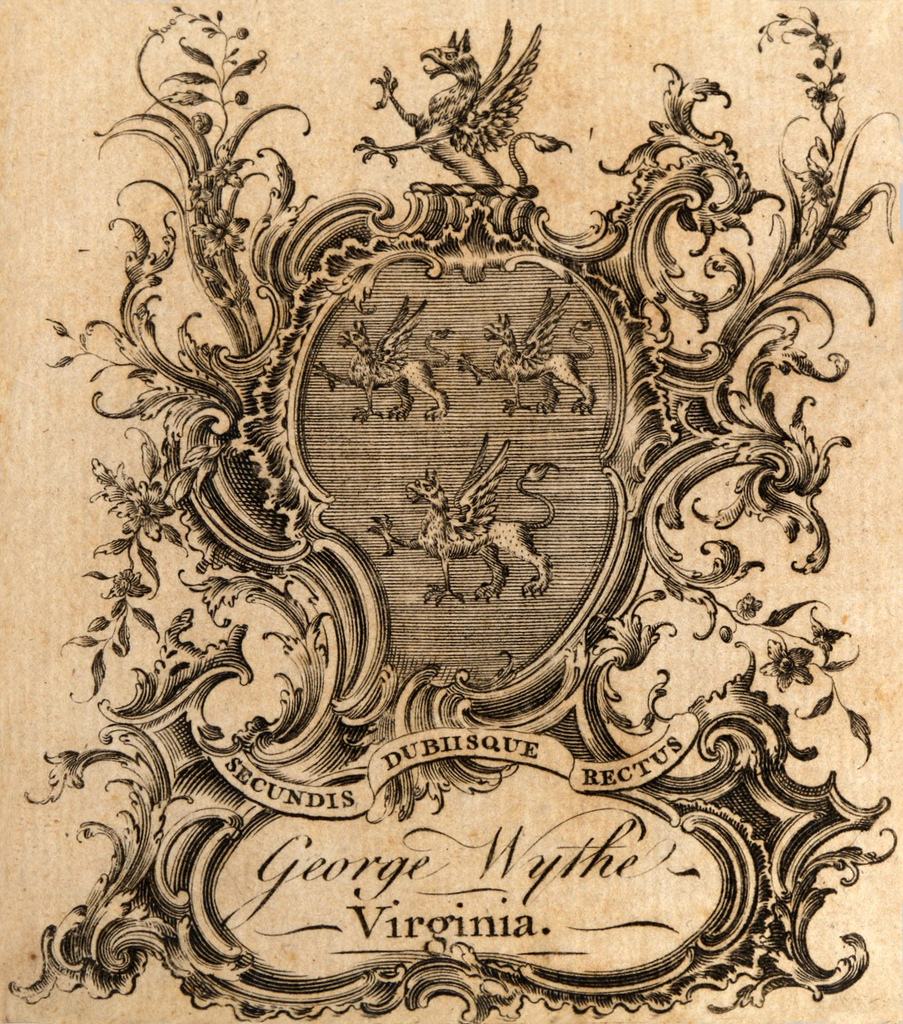

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

There is no doubt that George Wythe owned Les Reports de Sr. Creswell Levinz—a copy of the first edition (1702) at the Library of Congress includes Wythe's bookplate as well as annotations by Wythe and Thomas Jefferson.[9] Jefferson listed "Levinz’s [rep] 2.v. fol." in his inventory of Wythe's Library, noting that he kept the volume himself. He later sold it to the Library of Congress. Not surprisingly, all four of the Wythe Collection sources (Goodwin's pamphlet[10], Dean's Memo[11], Brown's Bibliography[12] and George Wythe's Library[13] on LibraryThing) list the first edition of Levinz's Reports.

As yet, the Wolf Law Library has not been able to purchase a copy of this title.

References

- ↑ D. E. C. Yale, "Levinz, Sir Creswell (1627–1701)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed February 16, 2015.

- ↑ John William Wallace, The Reporters, Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks, 4th ed., rev. and enl. (Boston: Soule and Bugbee, 1882), 306.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Wallace, The Reporters, Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks, 305.

- ↑ Edward Foss, Biographia Juridica: A Biographical Dictionary of the Judges of England from the Conquest to the Present Time, 1066-1870, (London: John Murray, 1870), 406-407.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Yale, "Levinz, Sir Creswell (1627–1701)."

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 2:343 [no.2068].

- ↑ Mary R. M. Goodwin, The George Wythe House: Its Furniture and Furnishings (Williamsburg, Virginia: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, 1958), XLV.

- ↑ Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean, Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 2, 6a, 4 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012, rev. May, 2014) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on March 4, 2015.