Difference between revisions of "Jefferson-Carr Correspondence"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | Between 30 December 1786 and 29 May 1789, Peter Carr and Thomas Jefferson engaged in a string of correspondence. The letters relate to Carr’s education, particularly his studies under George Wythe at William & Mary. As a private pupil of Wythe, Carr underwent a classical education, reading Herodotus, Sophocles, Cicero, Horace, and Lucretius, likely among many others. Carr describes a typical day of learning under Wythe: A 30 minute walk to begin the day, law before breakfast, languages until noon, philosophy until dinner, history after dinner, and poetry until bed time. In addition, the letters reveal that Carr was often invited to attend Wythe’s law lectures.<br /> | ||

| + | <br />Thomas Jefferson and Peter Carr’s letters reveal a high regard for Wythe’s intelligence and strength of character. Carr mentions that Wyth’s teachings went beyond traditional academic studies and included lessons on morality. He notes that, despite those who might call Wythe areligious, He fulfilled the great command of doing unto others and he would have done unto him. It was Jefferson’s hope that Carr, like he, would find studying under Wythe one of the most fortunate events of his life. Carr made it clear that Jefferson’s “sentiments with regard to Mr. Wythe, and the attention which ought to be paid to his precepts perfectly coincided.”<ref>[http://lawlibrary.wm.edu/wythepedia/index.php/Jefferson-Carr_Correspondence#Peter_Carr_to_Thomas_Jefferson.2C_29_May_1789 Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson], 29 May 1789.</ref> Nevertheless, Carr expressed the opinion that the time spent learning the dead languages might be better spent on other subjects that were more applicable to modern life. The letters reveal that both Carr and Jefferson were keenly interested in learning, a characteristic that must have been sparked by Wythe’s guidance and which would ultimately play a part in the two men’s founding of educational institutions a few decades later. | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

==Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 30 December 1786== | ==Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 30 December 1786== | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 11:00, 21 January 2015

Between 30 December 1786 and 29 May 1789, Peter Carr and Thomas Jefferson engaged in a string of correspondence. The letters relate to Carr’s education, particularly his studies under George Wythe at William & Mary. As a private pupil of Wythe, Carr underwent a classical education, reading Herodotus, Sophocles, Cicero, Horace, and Lucretius, likely among many others. Carr describes a typical day of learning under Wythe: A 30 minute walk to begin the day, law before breakfast, languages until noon, philosophy until dinner, history after dinner, and poetry until bed time. In addition, the letters reveal that Carr was often invited to attend Wythe’s law lectures.

Thomas Jefferson and Peter Carr’s letters reveal a high regard for Wythe’s intelligence and strength of character. Carr mentions that Wyth’s teachings went beyond traditional academic studies and included lessons on morality. He notes that, despite those who might call Wythe areligious, He fulfilled the great command of doing unto others and he would have done unto him. It was Jefferson’s hope that Carr, like he, would find studying under Wythe one of the most fortunate events of his life. Carr made it clear that Jefferson’s “sentiments with regard to Mr. Wythe, and the attention which ought to be paid to his precepts perfectly coincided.”[1] Nevertheless, Carr expressed the opinion that the time spent learning the dead languages might be better spent on other subjects that were more applicable to modern life. The letters reveal that both Carr and Jefferson were keenly interested in learning, a characteristic that must have been sparked by Wythe’s guidance and which would ultimately play a part in the two men’s founding of educational institutions a few decades later.

Contents

- 1 References

- 2 Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 30 December 1786

- 3 Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 18 April 1787

- 4 Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787

- 5 Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 18 March 1788

- 6 Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 6 August 1788

- 7 Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 29 May 1789

References

- ↑ Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 29 May 1789.

Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 30 December 1786

Hon’d. Sir Williamsburg Decembr. 30. 86.

A Ship being about to sail for Paris: I embrace the oppertunity of informing you (by Her) of my situation, and progress in Literature, since I wrote you last. I left the grammar school in April last; In consequence of a polite and Friendly invitation given me by Mr. Wythe, to go through a course of reading with him; And as He thought it improper to begin in the middle of a course of Lectures, I defer’d it untill October last which was the commencement of a new course. Here I attend the Professors of Moral and Natural philosophy, Mathematicks and Modern Languages and Mr. Wythe has invited me to attend His Lectures on Law. With respect to Modern Languages I have read French mostly, the want of a Spanish dictionary has retarded my advancement in that language.

Mr. Bellini has prevailed on me to begin Italian as he thinks by the time you can send me a Spanish dictionary, I may be a tolerable Master of that language, also that it will greatly facilitate my progress in Spanish. I received from you last Spring a trunk of books, at same time a letter for both of which you receive my greatfull thanks. I am now reading with Mr. Wythe the ancient history which you advised; am likewise reading the Tragedies of Aschylus, which as soon as I have finished I shall take up Aristophanes. You also advise me to read the works of Ossian, which I have done and should be more pleased with them if there were more variety. We have had very flattering accounts of my brother Sam lately. Dabney by the direction of Mr. Madison is at the Academy in prince Edward. My Mother and the family were well a few days ago; I also have the satisfaction to inform you Polly is well. Remember me Affectionately to my Cousin and believe me to be with due respect, Your affectionate Nephew,

Peter Carr

Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 18 April 1787

Dear Uncle Williamsburg, April 18th. ’87

Your daughter being about to sail to France gives me an opportunity of informing you of my situation and studies since I wrote last. I am still at the university attending the professors of Nat. and Mor. philosophy, Mathematicks and modern languages; and Mr. Wythe has given me a very friendly invitation to his lectures on law. I have likewise the good fortune to be a private pupil, and am now reading with him, Herodotus, Sophocles, Cicero and some particular parts of Horace. Beside the advantage of his literary instructions he adds advice and lessons of morality, which are not only pleasing and instructive now, but will be (I hope) of real utility in future. He is said to be without religion, but to me he appears to possess the most rational part of it, and fulfills that great command, Do unto all men as thou wouldst they should do unto thee. And now Sir I should be glad of your advice on the subject of religion; as I think it time to be fixed on a point which has had so many advocates and opponents, and still seems to be dubious. I should wish your advice as to the books I should read, and in what order. Mr. Wythe has just put Lucretius into my hands, whose sect and opinions, men generally think dangerous, but under so good a guide I fear not his opinions whatever they be, and hope rather to be benefited, than as some scrupulous people think, contaminated by him. I find nothing as disadvantageous and troubel some as attending too many things at once; I have unfortunately attempted it this year, and am apprehensive I shall have a perfect knowledge of none. I wish for a plan and order of study from you. I have the satisfaction to inform you that my brothers Sam and Dabney are in good situations, the first in Maryland and the second at an accademy in P. Edward under the direction of a Mr. Smith. I was very sorry to hear from Mr. Maury that you thought no American should go to Europe under thirty; I have, and ever had an invincible inclination to see the world, and am perfectly convinced (though my situation is as good as any in this country) that to see something of the world, get the polish of Europe, and mix the knowledge of books with that of men must be infinitely superior to any advantages enjoyed here. My health has been much injured by the air here. I never pass a summer or fall without a severe bilious fever. Present my compliments to my [300] Cousin Patsy and believe me to be with due respect and affection your nephew,

Peter Carr

Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787

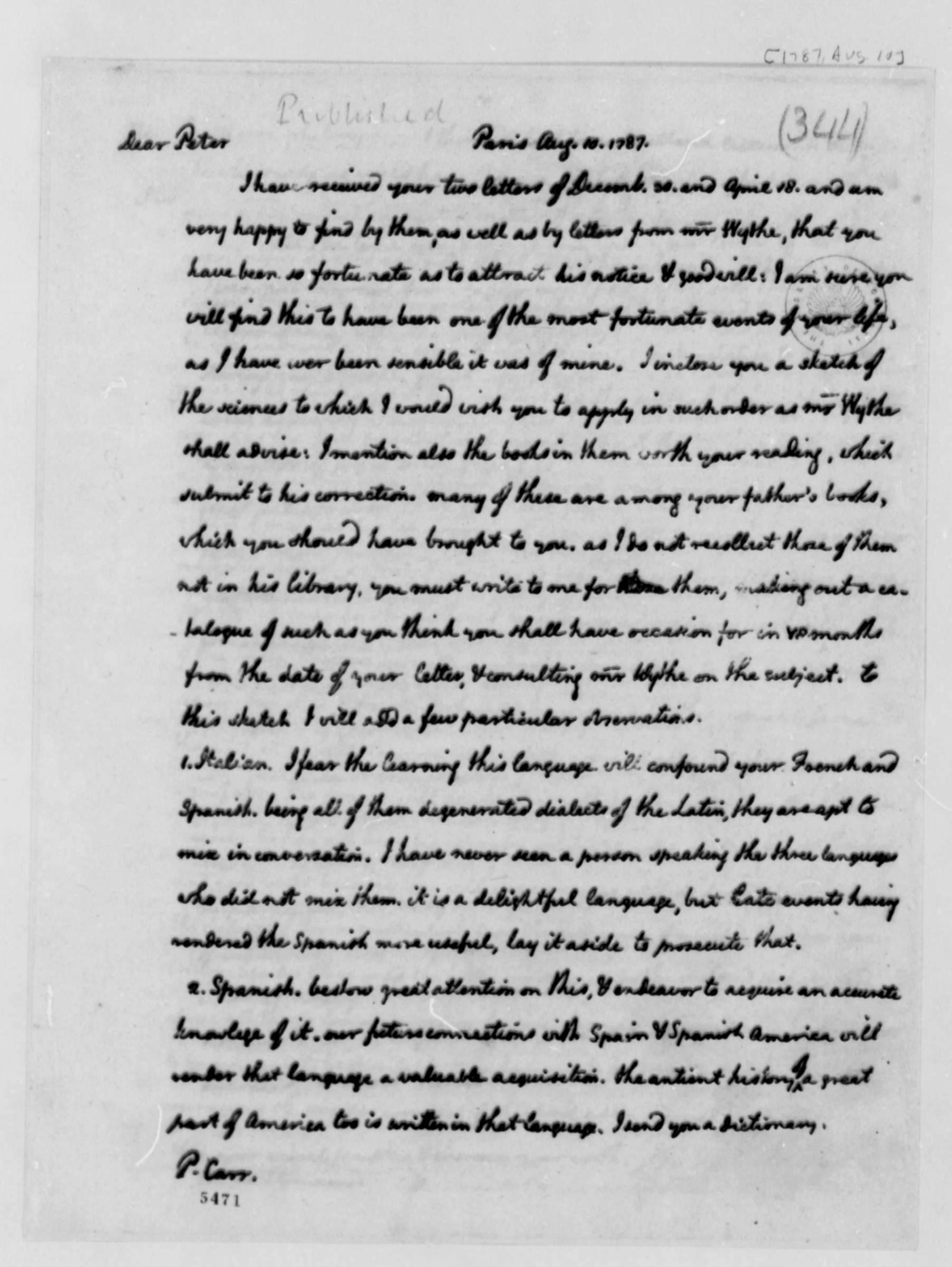

Page one of "Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787". Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

Dear Peter Paris Aug. 10. 1787.

I have received your two letters of Decemb. 30. and April 18. and am very happy to find by them, as well as by letters from Mr. Wythe, that you have been so fortunate as to attract his notice and good will: I am sure you will find this to have been one of the most fortunate events of your life, as I have ever been sensible it was of mine. I inclose you a sketch of the sciences to which I would wish you to apply in such order as Mr. Wythe shall advise: I mention also the books in them worth your reading, which submit to his correction. Many of these are among your father’s books, which you should have brought to you. As I do not recollect those of them not in his library, you must write to me for them, making out a catalogue of such as you think you shall have occasion for in 18 months from the date of your letter, and consulting Mr. Wythe on the subject. To this sketch I will add a few particular observations.

1. Italian. I fear the learning this language will confound your French and Spanish. Being all of them degenerated dialects of the Latin, they are apt to mix in conversation. I have never seen a person speaking the three languages who did not mix them. It is a delightful language, but late events having rendered the Spanish more useful, lay it aside to prosecute that.

2. Spanish. Bestow great attention on this, and endeavor to acquire an accurate knowlege of it. Our future connections with Spain and Spanish America will render that language a valuable acquisition. The antient history of a great part of America too is written in that language. I send you a dictionary.

Page 2

Page two of "Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787". Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

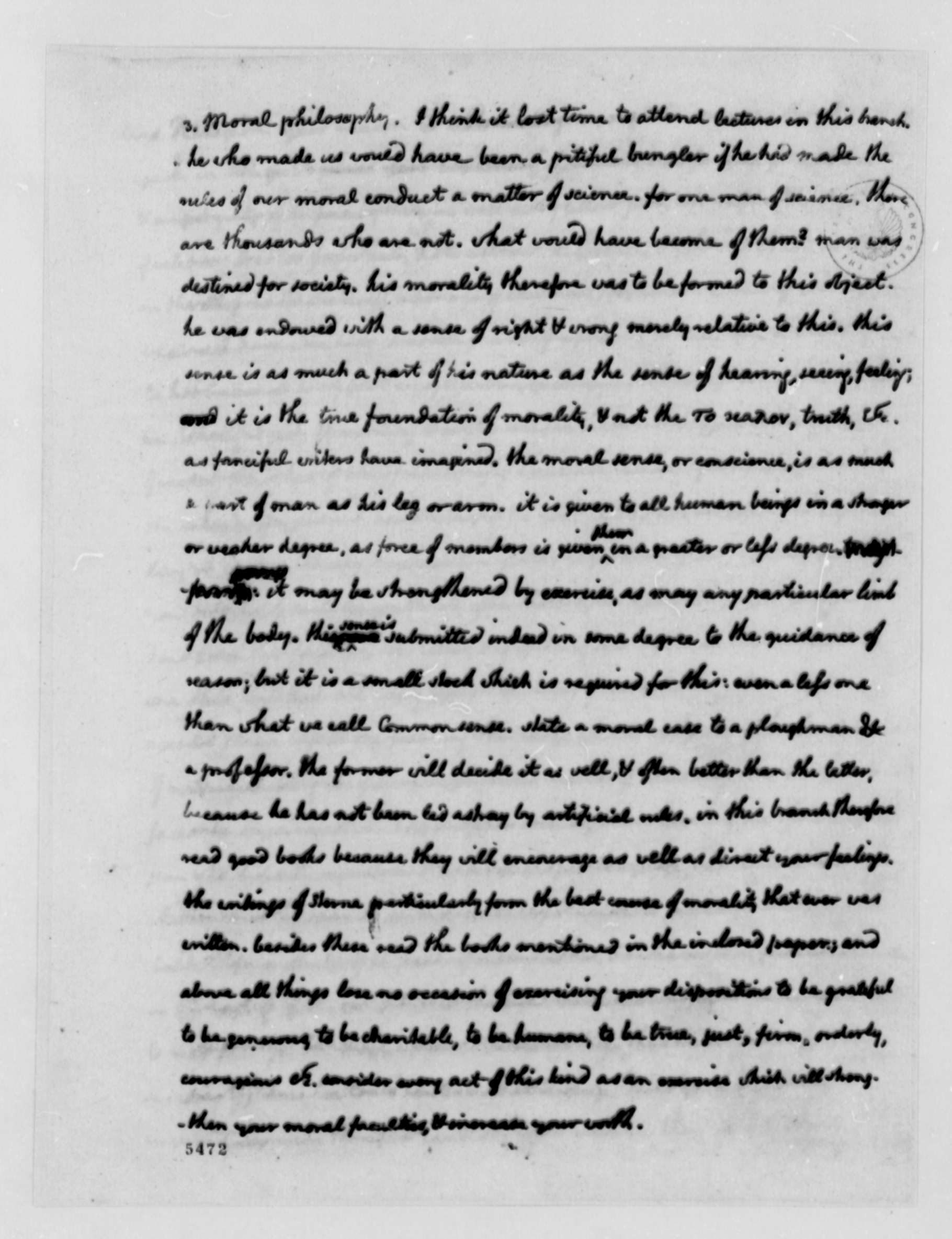

3. Moral philosophy. I think it lost time to attend lectures in this branch. He who made us would have been a pitiful bungler if he had made the rules of our moral conduct a matter of science. [15] For one man of science, there are thousands who are not. What would have become of them? Man was destined for society. His morality therefore was to be formed to this object. He was endowed with a sense of right and wrong merely relative to this. This sense is as much a part of his nature as the sense of hearing, seeing, feeling; it is the true foundation of morality, and not the truth, &c., as fanciful writers have imagined. The moral sense, or conscience, is as much a part of man as his leg or arm. It is given to all human beings in a stronger or weaker degree, as force of members is given them in a greater or less degree. It may be strengthened by exercise, as may any particular limb of the body. This sense is submitted indeed in some degree to the guidance of reason; but it is a small stock which is required for this: even a less one than what we call Common sense. State a moral case to a ploughman and a professor. The former will decide it as well, and often better than the latter, because he has not been led astray by artificial rules. In this branch therefore read good books because they will encourage as well as direct your feelings. The writings of Sterne particularly form the best course of morality that ever was written. Besides these read the books mentioned in the inclosed paper; and above all things lose no occasion of exercising your dispositions to be grateful, to be generous, to be charitable, to be humane, to be true, just, firm, orderly, couragious &c. Consider every act of this kind as an exercise which will strengthen your moral faculties, and increase your worth.

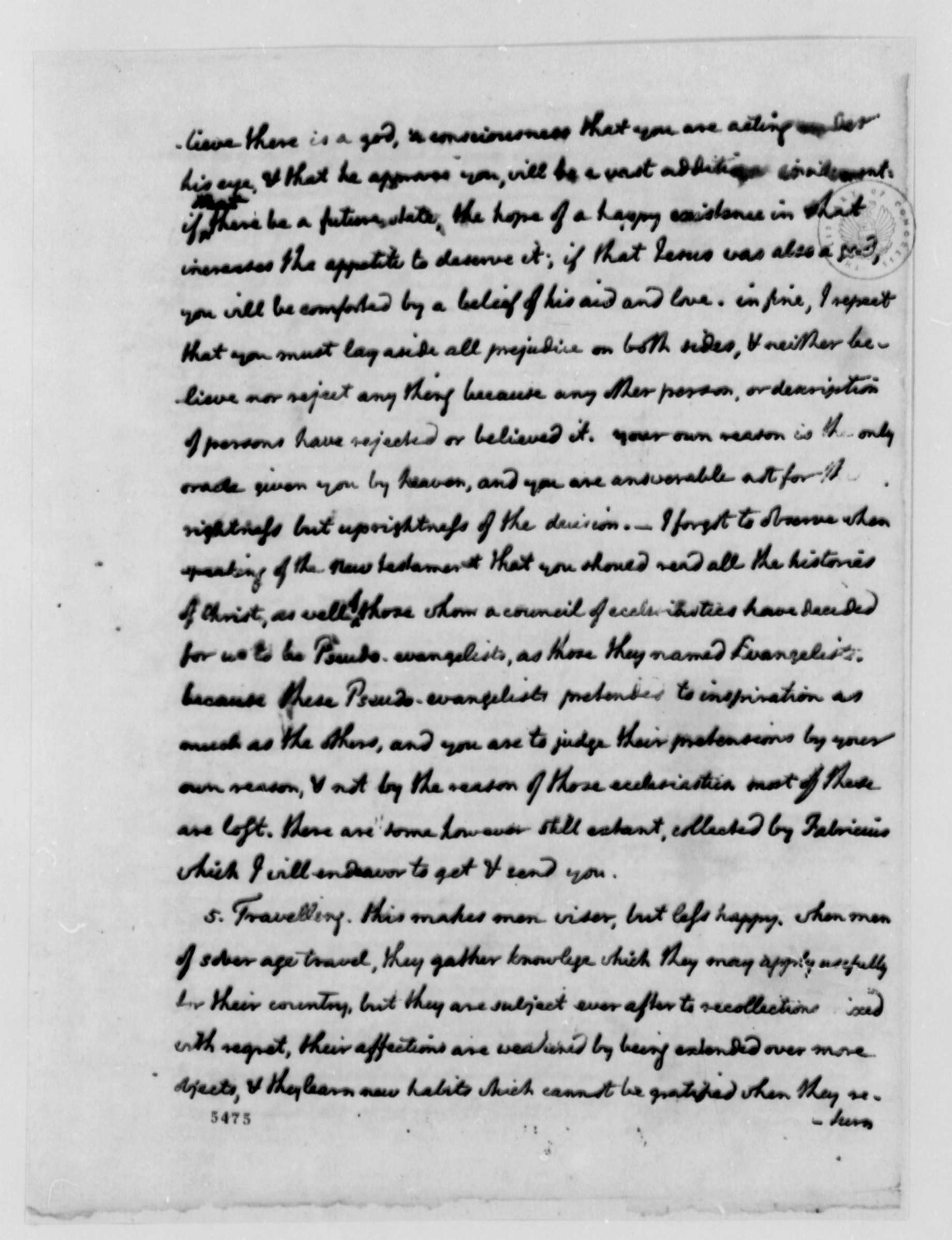

Page 3

Page three of "Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787". Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

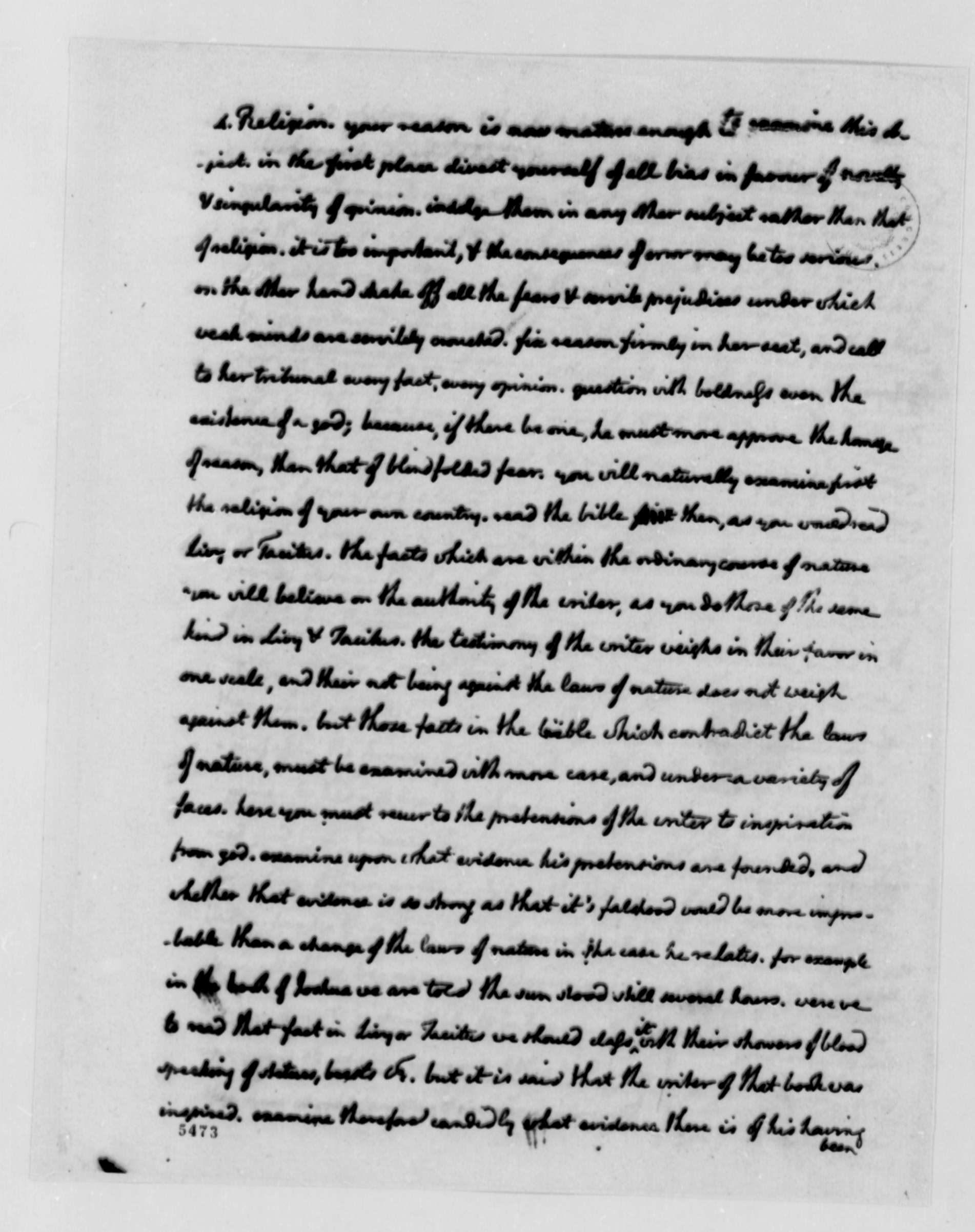

4. Religion. Your reason is now mature enough to receive this object. In the first place divest yourself of all bias in favour of novelty and singularity of opinion. Indulge them in any other subject rather than that of religion. It is too important, and the consequences of error may be too serious. On the other hand shake off all the fears and servile prejudices under which weak minds are servilely crouched. Fix reason firmly in her seat, and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a god; because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason, than that of blindfolded fear. You will naturally examine first the religion of your own country. Read the bible then, as you would read Livy or Tacitus. The facts which are within the ordinary course of nature you will believe on the authority of the writer, as you do those of the same kind in Livy and Tacitus. The testimony of the writer weighs in their favor in one scale, and their not being against the laws of nature does not [16] weigh against them. But those facts in the bible which contradict the laws of nature, must be examined with more care, and under a variety of faces. Here you must recur to the pretensions of the writer to inspiration from god. Examine upon what evidence his pretensions are founded, and whether that evidence is so strong as that it’s falshood would be more improbable than a change of the laws of nature in the case he relates For example in the book of Joshua we are told the sun stood still several hours. Were we to read that fact in Livy or Tacitus we should class it with their showers of blood, speaking of statues, beasts &c., but it is said that the writer of that book was inspired. Examine therefore candidly what evidence there is of his having

Page 4

Page four of "Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787". Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

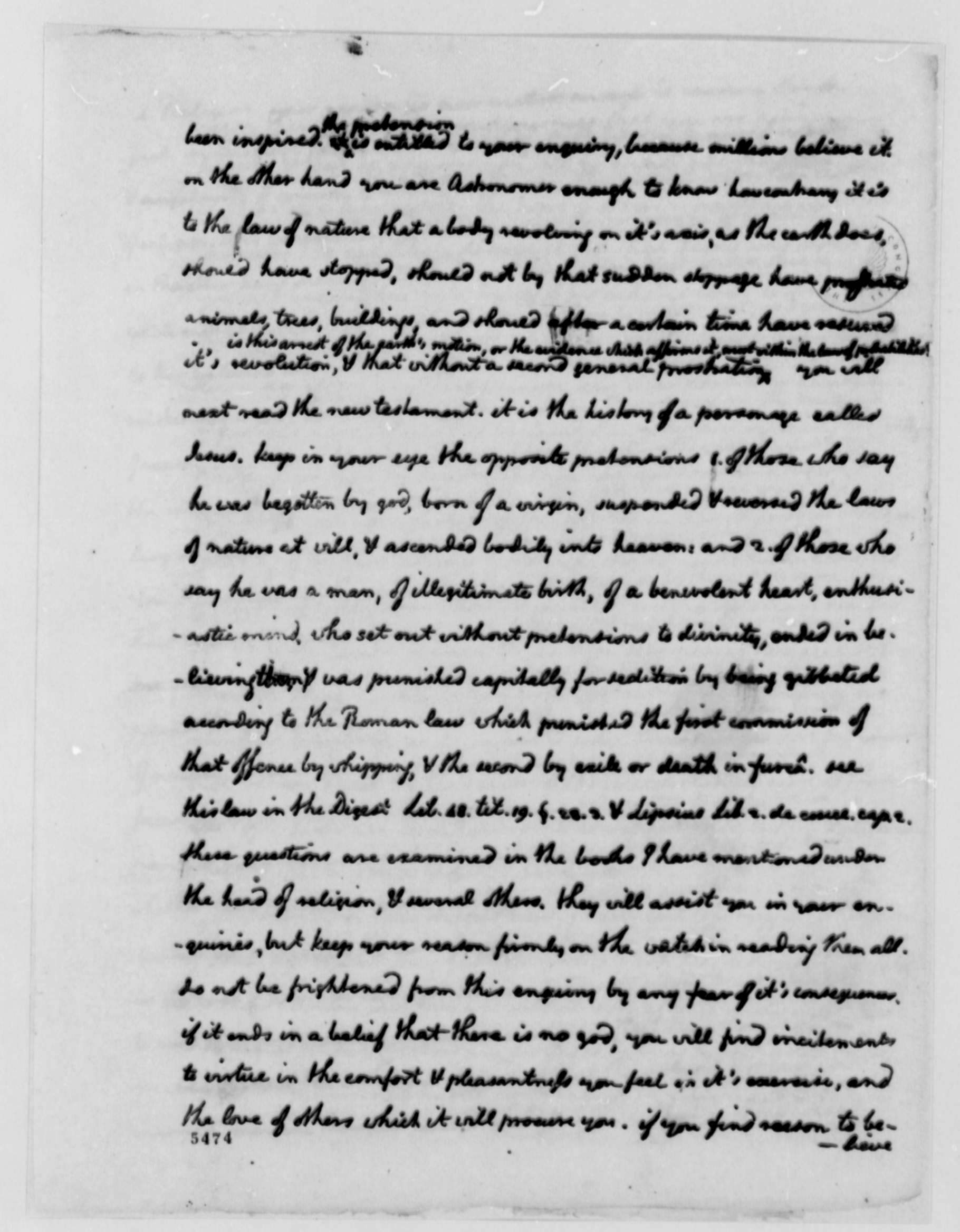

been inspired. The pretension is entitled to your enquiry, because millions believe it. On the other hand you are Astronomer enough to know how contrary it is to the law of nature that a body revolving on it’s axis, as the earth does, should have stopped, should not by that sudden stoppage have prostrated animals, trees, buildings, and should after a certain time have resumed it’s revolution, and that without a second general prostration. Is this arrest of the earth’s motion, or the evidence which affirms it, most within the law of probabilities? You will next read the new testament. It is the history of a personage called Jesus. Keep in your eye the opposite pretensions. 1. Of those who say he was begotten by god, born of a virgin, suspended and reversed the laws of nature at will, and ascended bodily into heaven: and 2. of those who say he was a man, of illegitimate birth, of a benevolent heart, enthusiastic mind, who set out without pretensions to divinity, ended in believing them, and was punished capitally for sedition by being gibbeted according to the Roman law which punished the first commission of that offence by whipping, and the second by exile or death in furcâ. See this law in the Digest Lib. 48. tit. 19 § 28. 3. and Lipsius Lib. 2. de cruce. cap. 2. These questions are examined in the books I have mentioned under the head of religion, and several others. They will assist you in your enquiries, but keep your reason firmly on the watch in reading them all. Do not be frightened from this enquiry by any fear of it’s consequences. If it ends in a belief that there is no god, you will find incitements to virtue in the comfort and pleasantness you feel in it’s exercise, and the love of others which it will procure you. If you find reason to believe

Page 5

Page one of "Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787". Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

-lieve there is a god, a consciousness that you are acting under his eye, and that he approves you, will be a vast additional incitement. If that there be a future state, the hope [17] of a happy existence in that increases the appetite to deserve it; if that Jesus was also a god, you will be comforted by a belief of his aid and love. In fine, I repeat that you must lay aside all prejudice on both sides, and neither believe nor reject any thing because any other person, or description of persons have rejected or believed it. Your own reason is the only oracle given you by heaven, and you are answerable not for the rightness but uprightness of the decision.—I forgot to observe when speaking of the New testament that you should read all the histories of Christ, as well of those whom a council of ecclesiastics have decided for us to be Pseudo-evangelists, as those they named Evangelists, because these Pseudo-evangelists pretended to inspiration as much as the others, and you are to judge their pretensions by your own reason, and not by the reason of those ecclesiastics. Most of these are lost. There are some however still extant, collected by Fabricius which I will endeavor to get and send you.

5. Travelling. This makes men wiser, but less happy. When men of sober age travel, they gather knowlege which they may apply usefully for their country, but they are subject ever after to recollections mixed with regret, their affections are weakened by being extended over more objects, and they learn new habits which cannot be gratified when they return

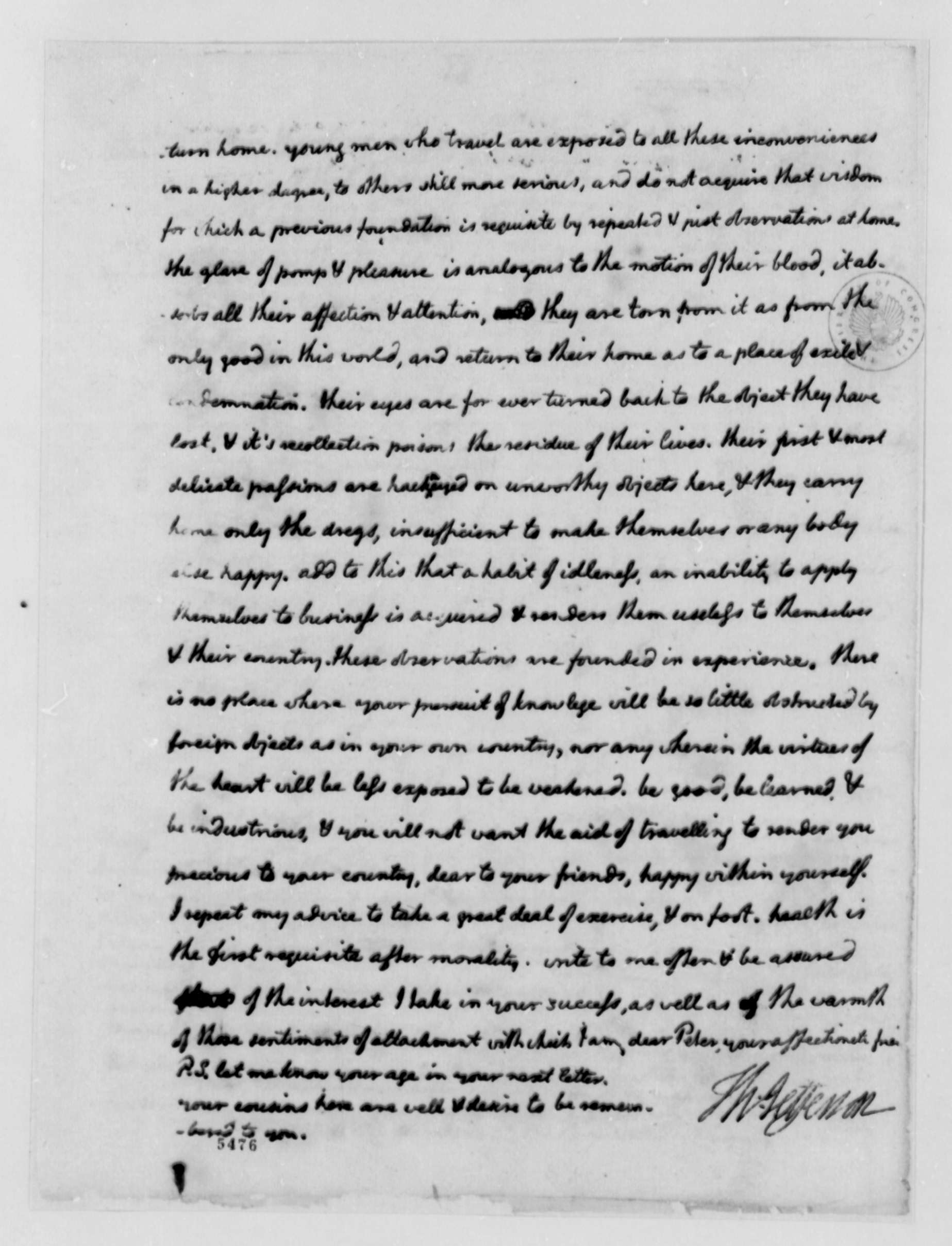

Page 6

Page six of "Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787". Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

return home. Young men who travel are exposed to all these inconveniences in a higher degree, to others still more serious, and do not acquire that wisdom for which a previous foundation is requisite by repeated and just observations at home. The glare of pomp and pleasure is analogous to the motion of their blood, it absorbs all their affection and attention, they are torn from it as from the only good in this world, and return to their home as to a place of exile and condemnation. Their eyes are for ever turned back to the object they have lost, and it’s recollection poisons the residue of their lives. Their first and most delicate passions are hackneyed on unworthy objects here, and they carry home only the dregs, insufficient to make themselves or any body else happy. Add to this that a habit of idleness, an inability to apply themselves to business is acquired and renders them useless to themselves and their country. These observations are founded in experience. There is no place where your pursuit of knowlege will be so little obstructed by foreign objects as in your own country, nor any wherein the virtues of the heart will be less exposed to be weakened. Be good, be learned, and be industrious, and you will not want the aid of travelling to render you [18] precious to your country, dear to your friends, happy within yourself. I repeat my advice to take a great deal of exercise, and on foot. Health is the first requisite after morality. Write to me often and be assured of the interest I take in your success, as well as of the warmth of those sentiments of attachment with which I am, dear Peter, your affectionate friend,

Th: Jefferson

P.S. Let me know your age in your next letter. Your cousins here are well and desire to be remembered to you.

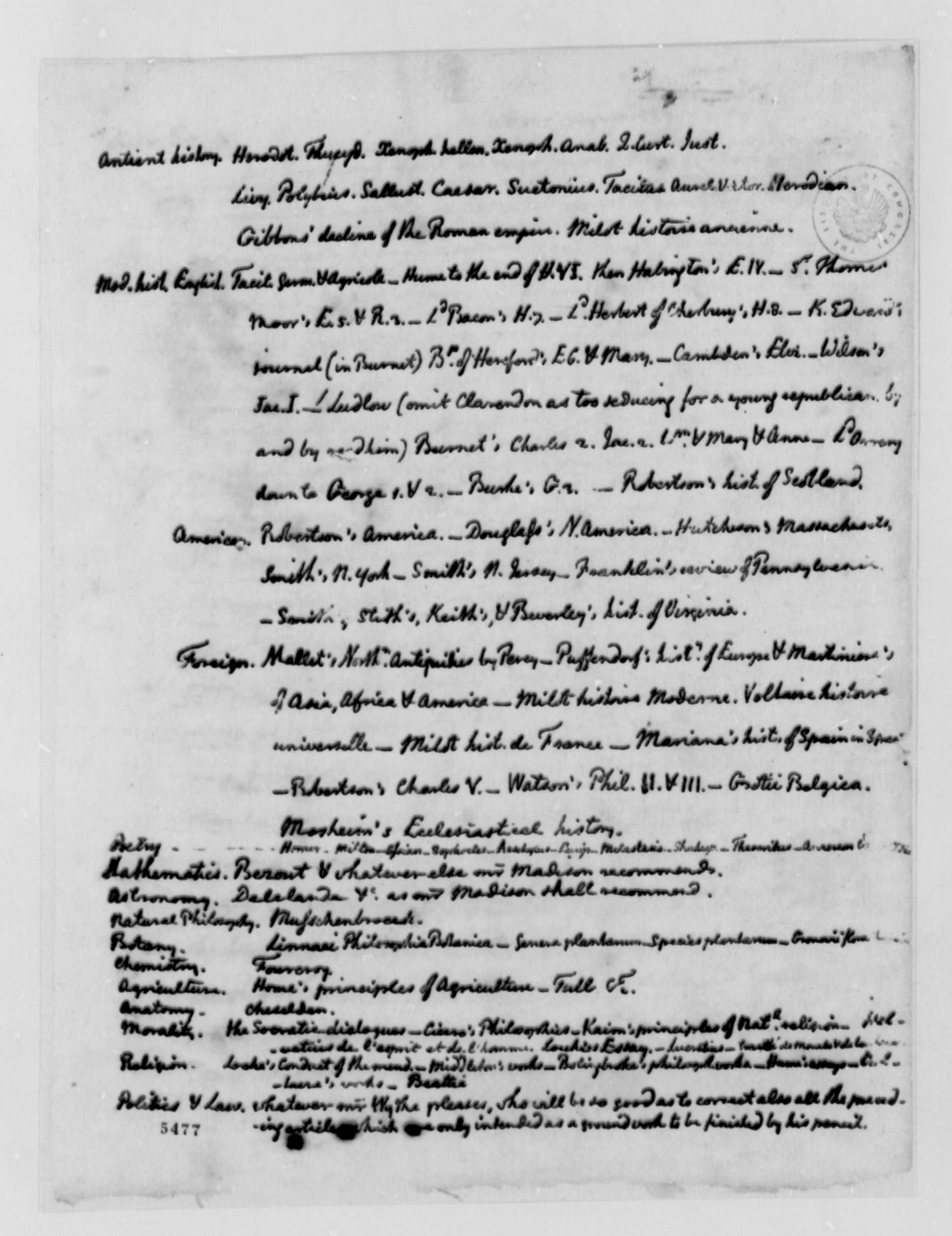

Enclosure

Enclosure from "Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 10 August 1787". Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

Antient history. Herodot. Thucyd. Xenoph. hellen. Xenoph. Anab. Q. Curt. Just. Livy. Polybius. Sallust. Caesar. Suetonius. Tacitus. Aurel. Victor. Herodian. Gibbons’ decline of the Roman empire. Milot histoire ancienne.

Mod. hist. English. Tacit. Germ. & Agricole. Hume to the end of H.VI. then Habington’s E.IV.-Sr. Thomas Moor’s E.5. & R.3.-Ld. Bacon’s H.7.—Ld. Herbert of Cherbury’s H.8.—K. Edward’s journal (in Burnet) Bp. of Hereford’s E.6. & Mary.-Cambden’s Eliz. Wilson’s Jac.I. Ludlow (omit Clarendon as too seducing for a young republican. By and by read him) Burnet’s Charles 2. Jac.2. Wm. & Mary & Anne.—Ld. Orrery down to George 1. & 2.—Burke’s G.3. Robertson’s hist. of Scotland.

American. Robertson’s America.—Douglass’s N. America.—Hutcheson’s Massachusets, Smith’s N. York.—Smith’s N. Jersey.—Franklin’s review of Pennsylvania. Smith’s, Stith’s, Keith’s, & Beverley’s hist. of Virginia.

Foreign. Mallet’s Northn. Antiquities by Percy.—Puffendorf’s histy. of Europe & Martiniere’s of Asia, Africa & America.—Milot histoire Moderne. Voltaire histoire universelle.—Milot hist. de France.—Mariana’s hist. of Spain in Spa[nish.]—Robertson’s Charles V.—Watson’s Phil. II. & III.-Grotii Belgica. Mosheim’s Ecclesiastical history.

Poetry. Homer—Milton—Ossian—Sophocles—Aeschylus—Eurip.—Metastasio—Shakesp.—Theocritus—Anacreon […]

Mathematics. Bezout & whatever else Mr. Madison recommends.

Astronomy. Delalande &c. as Mr. Madison shall recommend.

Natural Philosophy. Musschenbroeck.

Botany. Linnaei Philosophia Botanica—Genera Plantarum—Species plantarum—Gronovii flora [Virginica.]

Chemistry. Fourcroy.

Agriculture. Home’s principles of Agriculture—Tull &c.

Anatomy. Cheselden.

Morality. The Socratic dialogues—Cicero’s Philosophies—Kaim’s principles of Natl. religion—Helvetius de l’esprit et de l’homme. Locke’s Essay.—Lucretius—Traité de Morale & du Bon[heur]

Religion. Locke’s Conduct of the mind.—Middleton’s works—Bolingbroke’s [19] philosoph. works—Hume’s essays—Voltaire’s works—Beattie.

Politics & Law. Whatever Mr. Wythe pleases, who will be so good as to correct also all the preceding articles which are only intended as a ground work to be finished by his pencil.

Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 18 March 1788

Dear Uncle Williamsburg—March. 18–1788

Mr. Paradise being about to sail to Europe in a few days, furnishes me with an opportunity of informing you of my progress and situation. In my letter of the 10 December I acquainted you, that from the want of money I had been obliged to stay in Goochland, some time; soon after the date of that, I was fortunate enough to receive some, and return’d to this place immediately. Mr. Wythe advised me to begin the study of the Law, reading it two or three hours every day, and devoteing the rest of my time to the languages, history and Philosophy; but that you may know how I imploy every hour of the day I will give it you in detail. I rise about day, and take a walk of half an hour to shake off sleep, read law till breakfast, then attend Mr. Wythe till 12 oclock in the languages, read philosophy till dinner, history till night, and poetry till bed time. Mr. Paradise has lately presented me with the history of Greece by Gillies, together with Priestley’s historical chart, each of which I shall endeavour to use in such manner as to merit them. The Books you mention in your letter to Mr. Wythe have never yet come to hand, when they do I hope to profit by those, which you mention are for me. My mother and family are well, and desire to be remembered to yourself and daughters. Accept of my sincere wishes for your health and welfare, and believe me to be your Dutiful and affectionate nephew,

Peter Carr

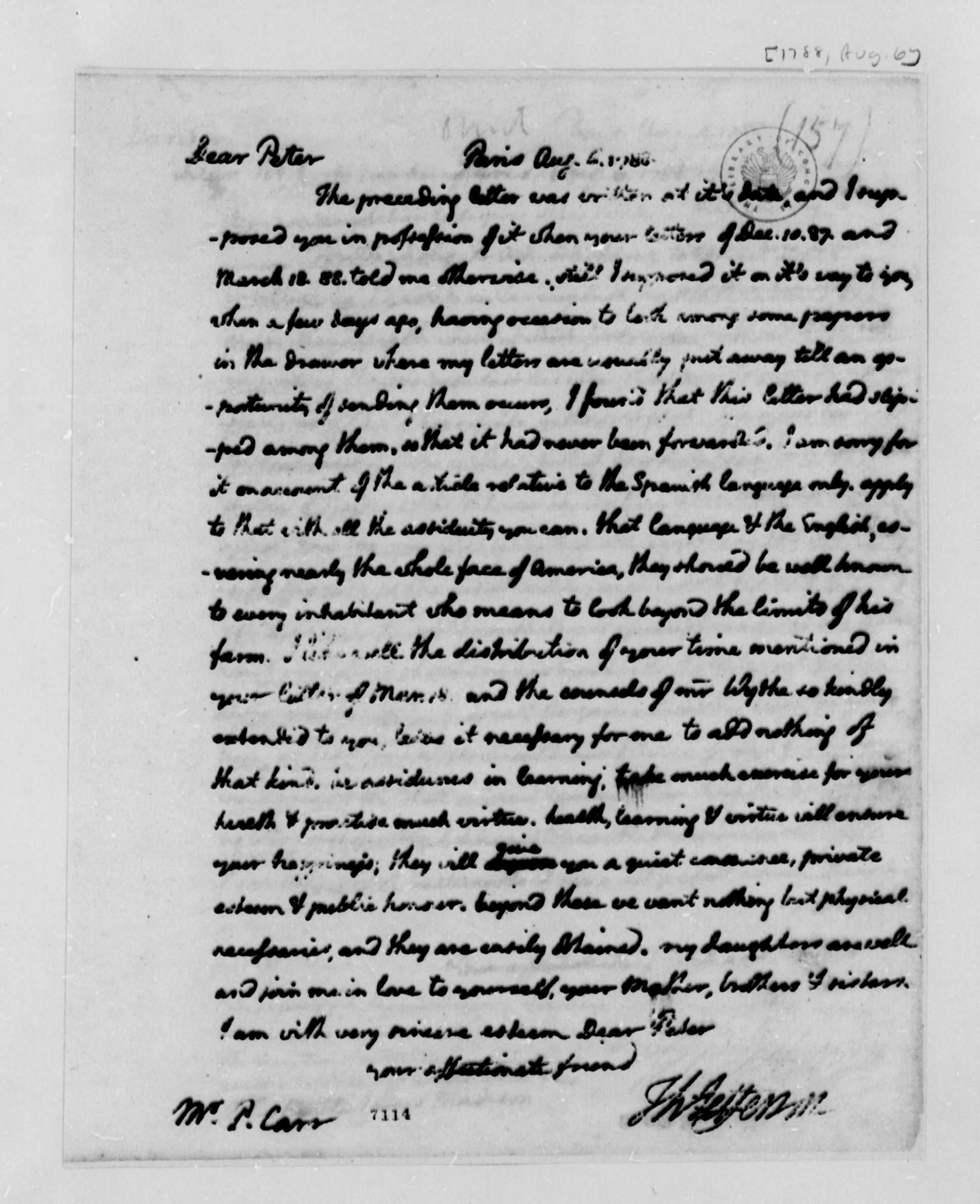

Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 6 August 1788

"Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 6 August 1788". Image from the Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

Dear Peter Paris Aug. 6. 1788.

The preceding letter was written at it’s date, and I supposed you in possession of it when your letters of Dec. 10. 87. and March 18. 88. told me otherwise. Still I supposed it on it’s way to you, when a few days ago, having occasion to look among some papers in the drawer where my letters are usually put away till an opportunity of sending them occurs, I found that this letter had slipped among them, so that it had never been forwarded. I am sorry for it on account of the article relative to the Spanish language only. Apply to that with all the assiduity you can. That language and the English, covering nearly the whole face of America, they should be well known to every inhabitant who means to look beyond the limits of his farm. I like well the distribution of your time mentioned in your letter of Mar. 18. and the counsels of Mr. Wythe so kindly extended to you, leave it necessary for me to add nothing of that kind. Be assiduous in learning, take much exercise for your health and practise much virtue. Health, learning and virtue will ensure your happiness; they will give you a quiet conscience, private esteem and public honour. Beyond these we want nothing but physical necessaries, and they are easily obtained. My daughters are well and join me in love to yourself, your Mother, brothers and sisters. I am with very sincere esteem Dear Peter your affectionate friend,

Th: Jefferson

P.S. Present me affectionately to Mr. Wythe.

Peter Carr to Thomas Jefferson, 29 May 1789

Dear Uncle New York. May 29. 89.

Your two letters of August 10. 87 and August 6th. 88 came to hand some time in November last; they should have been immediately [156] answered, had not a long and severe indisposition prevented me: When my health would have permited, the season was so far advanced, that I thought it better to wait till this time.

The spring vacation at Wm. & Mary has given me an opportunity of spending some time here; with the advice of Mr. Madison in my reading, and the advantage of attending the debates of the two houses, I hope it will not pass unprofitably. Thos. Randolph of Tuckhoe (whom I find extremely intelligent and cleaver) lives with me. He intends to remain here till October, and then return to Virginia. If Mr. Madison approves of it I mean to stay with him; the difference between this place and Wmsburg. with respect to expence will be little; and the advantages to be gained here great. I hope therefore he will not object. Before I left Virginia it was said you had sail’d for America, accompanied by your daughters. Would to god, it were so! but Mr. Madison tells me there is no probability of it this summer at least.

Your sentiments with regard to Mr. Wythe, and the attention which ought to be paid to his precepts perfectly coincide with mine; his public avocations have lately taken up much of his time: so that my attendance on him has not been such as I could have wished. However I have attended to those things which he advised, and taken his counsel whenever I had doubts. The mode of education which he pursues, and to which he is so much attached, is in a measure fallen into disuse, and for my own part I think not entirely without reason. Might not a great part of that time which he bestows on the dead languages, be better employed on the modern languages, natural history, and the Mathematics? I really think it might. Mr. Randolph tells me he has known surprising advantages result from the latter plan. I would not be understood to hint, however, that a knowledge of the Ancient languages is altogether useless. I only mean to suggest a doubt whether that strict and constant attention is necessary, and whether part of it might not be better applied.

I receiv’d in your last letter a catalogue of books, and you mention that there are many of them in my fathers library. I have examined and find there is not one mentioned in your catalogue among them. Your reasons for declining the Italian (although I think it a delightful language) are so conclusive that I have laid it aside. I am well convinced of the utility of the Spanish, and shall endeavour to acquire a competent knowledge of it. In the pronunciation I fear I shall be deficient, as I have met with no person who professedly teaches it.

Mr. Smith gives very favourable accounts of Dabney’s genius and dispositions. Saml. is at Wm. & Mary-not bright-but I hope not destitute of genius. Remember me to my Cousins, and Believe me to be Dr Sir, Your dutiful nephew, and affectionate friend,

Peter Carr

P.S. I was born the 2d. of January 1770.