Difference between revisions of "Reports of Sir Edward Coke"

(JH edits) |

(fn edits) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

|display=left | |display=left | ||

|caption=Bookplates of George Wythe and Tazewell Taylor, front pastedown, volume six. | |caption=Bookplates of George Wythe and Tazewell Taylor, front pastedown, volume six. | ||

| − | }}Born on February 1, 1552 at Mileham, Norfolk, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Coke Sir Edward Coke] (1552-1634) was arguably the most prominent lawyer, legal writer, and politician during the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, and a defender of the common law over the use of the Stuarts' royal prerogative.<ref>''Encyclopaedia Britannica Online'', s. v. "[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/124844/Sir-Edward-Coke Sir Edward Coke]," accessed October 3, 2013.</ref><br /> | + | }}Born on February 1, 1552 at Mileham, Norfolk, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Coke Sir Edward Coke] (1552-1634) was arguably the most prominent lawyer, legal writer, and politician during the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, and a defender of the common law over the use of the Stuarts' royal prerogative.<ref>''Encyclopaedia Britannica Online'', s.v. "[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/124844/Sir-Edward-Coke Sir Edward Coke]," accessed October 3, 2013.</ref><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | Coke began his studies in 1567 at [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinity_College,_Cambridge Trinity College, Cambridge] during the years of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vestiarian_controversy Vestiarian controversy]—puritan protests against the Church of England. In 1572 he moved on to study at the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inner_Temple Inner Temple], where he was admitted to the bar on April 20, 1578. Coke quickly rose to prominence through his successful execution of several noteworthy cases, such as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rule_in_Shelley%27s_Case ''Shelley’s'' case]. Coke's analytical efforts helped to refine the legal doctrines of English law, and his reputation won him a seat in Parliament. He would later become the Speaker of the House of Commons and eventually attorney general.<ref>Allen D. Boyer, [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.wm.edu/view/article/5826 | + | Coke began his studies in 1567 at [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinity_College,_Cambridge Trinity College, Cambridge] during the years of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vestiarian_controversy Vestiarian controversy]—puritan protests against the Church of England. In 1572 he moved on to study at the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inner_Temple Inner Temple], where he was admitted to the bar on April 20, 1578. Coke quickly rose to prominence through his successful execution of several noteworthy cases, such as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rule_in_Shelley%27s_Case ''Shelley’s'' case]. Coke's analytical efforts helped to refine the legal doctrines of English law, and his reputation won him a seat in Parliament. He would later become the Speaker of the House of Commons and eventually attorney general.<ref>Allen D. Boyer, "[http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.wm.edu/view/article/5826 Coke, Sir Edward (1552–1634)]" in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', accessed September 18, 2013.</ref> In 1606, after being created [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serjeant-at-law serjeant-at-law], Coke was appointed chief justice of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_of_Common_Pleas_%28England%29 Court of Common Pleas]. He was transferred, against his will, to chief justice of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_of_King%27s_Bench_%28England%29 Court of King's Bench] in 1613; he also became a member of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Privy_Council_of_the_United_Kingdom privy council].<ref>Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."</ref><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | After several political and judicial skirmishes with [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_VI_and_I James I] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon Francis Bacon], Coke was suspended from the privy council and removed from the bench in 1616.<ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica Online'', s. v. "Sir Edward Coke."</ref> Although he never returned to the bench, Coke did return to Parliament and was elected to that body four times from 1620 to 1629. During this time he took a lead in creating and composing the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petition_of_Right Petition of Right]. "This document cited the Magna Carta and reminded Charles I that the law gave Englishmen their rights, not the king ... Coke’s petition focused on ... due process, protection from unjust seizure of property or imprisonment, the right to trial by jury of fellow Englishmen, and protection from unjust punishments or excessive fines."<ref>''Bill of Rights Institute'' website, s.v. | + | After several political and judicial skirmishes with [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_VI_and_I James I] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon Francis Bacon], Coke was suspended from the privy council and removed from the bench in 1616.<ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica Online'', s.v. "Sir Edward Coke."</ref> Although he never returned to the bench, Coke did return to Parliament and was elected to that body four times from 1620 to 1629. During this time he took a lead in creating and composing the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petition_of_Right Petition of Right]. "This document cited the Magna Carta and reminded Charles I that the law gave Englishmen their rights, not the king ... Coke’s petition focused on ... due process, protection from unjust seizure of property or imprisonment, the right to trial by jury of fellow Englishmen, and protection from unjust punishments or excessive fines."<ref>''Bill of Rights Institute'' website, s.v. [http://billofrightsinstitute.org/resources/educator-resources/americapedia/americapedia-documents/petition-of-right/ "Petition of Right (1628)]," accessed October 3, 2013.</ref> After this triumph, Coke spent his remaining years at his home, Stoke Poges, working on ''The Institutes of the Laws of England'', another endeavor for which he is rightly famous.<ref>Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."</ref><br /> |

<blockquote>"Coke's first well-known work was a manuscript report of Shelley's case, circulated soon after the decision in 1581. In 1600, afraid that unauthorized versions of his case reports might be printed—and probably following the example of Edmund Plowden, with whom he had worked and whom he revered—Coke issued the First Part of his Reports. He put out eleven volumes by 1615. Making available more than 467 cases, carrying the imprimatur and the authority of the lord chief justice, these case reports provided a critical mass of material for the rapidly developing modern common law. Reversing medieval jurisprudence, which had often relied on general learning and reason, Coke preferred to amass precedents. ‘The reporting of particular cases or examples’, he asserted, was ‘the most perspicuous course of teaching the right rule and reason of the law’ (E. Coke, Reports, 1600–1659, 4, preface). | <blockquote>"Coke's first well-known work was a manuscript report of Shelley's case, circulated soon after the decision in 1581. In 1600, afraid that unauthorized versions of his case reports might be printed—and probably following the example of Edmund Plowden, with whom he had worked and whom he revered—Coke issued the First Part of his Reports. He put out eleven volumes by 1615. Making available more than 467 cases, carrying the imprimatur and the authority of the lord chief justice, these case reports provided a critical mass of material for the rapidly developing modern common law. Reversing medieval jurisprudence, which had often relied on general learning and reason, Coke preferred to amass precedents. ‘The reporting of particular cases or examples’, he asserted, was ‘the most perspicuous course of teaching the right rule and reason of the law’ (E. Coke, Reports, 1600–1659, 4, preface). | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

| − | Wythe definitely owned this title—copies of volumes six and seven of the 1738 edition at the College of William & Mary include [[George Wythe's bookplate|his bookplate]] and an inscription on the inside front board, "Given by Thos. Jefferson to D. Carr, 1806." Surprisingly, ''Coke's Reports'' is not listed in the [[Jefferson Inventory]] of [[Wythe's Library]]. Perhaps this was an oversight on Jefferson's part, or the title appeared on a lost or damaged page. Three of the [[George Wythe Collection|Wythe Collection]] sources ([[Dean Bibliography|Dean's Memo]],<ref>[[Dean Bibliography|Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean]], Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 10 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).</ref>, Brown's Bibliography<ref>Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.</ref> and [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s. v. "[http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe Member: George Wythe | + | Wythe definitely owned this title—copies of volumes six and seven of the 1738 edition at the College of William & Mary include [[George Wythe's bookplate|his bookplate]] and an inscription on the inside front board, "Given by Thos. Jefferson to D. Carr, 1806." Surprisingly, ''Coke's Reports'' is not listed in the [[Jefferson Inventory]] of [[Wythe's Library]]. Perhaps this was an oversight on Jefferson's part, or the title appeared on a lost or damaged page. Three of the [[George Wythe Collection|Wythe Collection]] sources ([[Dean Bibliography|Dean's Memo]],<ref>[[Dean Bibliography|Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean]], Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 10 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).</ref>, Brown's Bibliography<ref>Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.</ref> and [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s.v. "[http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe Member: George Wythe]," accessed on June 28, 2013</ref> on LibraryThing) list the 1738 edition of this title. |

==Description of Wolf Law Library's copy== | ==Description of Wolf Law Library's copy== | ||

Revision as of 14:36, 15 April 2014

by Sir Edward Coke

| The Reports of Sir Edward Coke | |

|

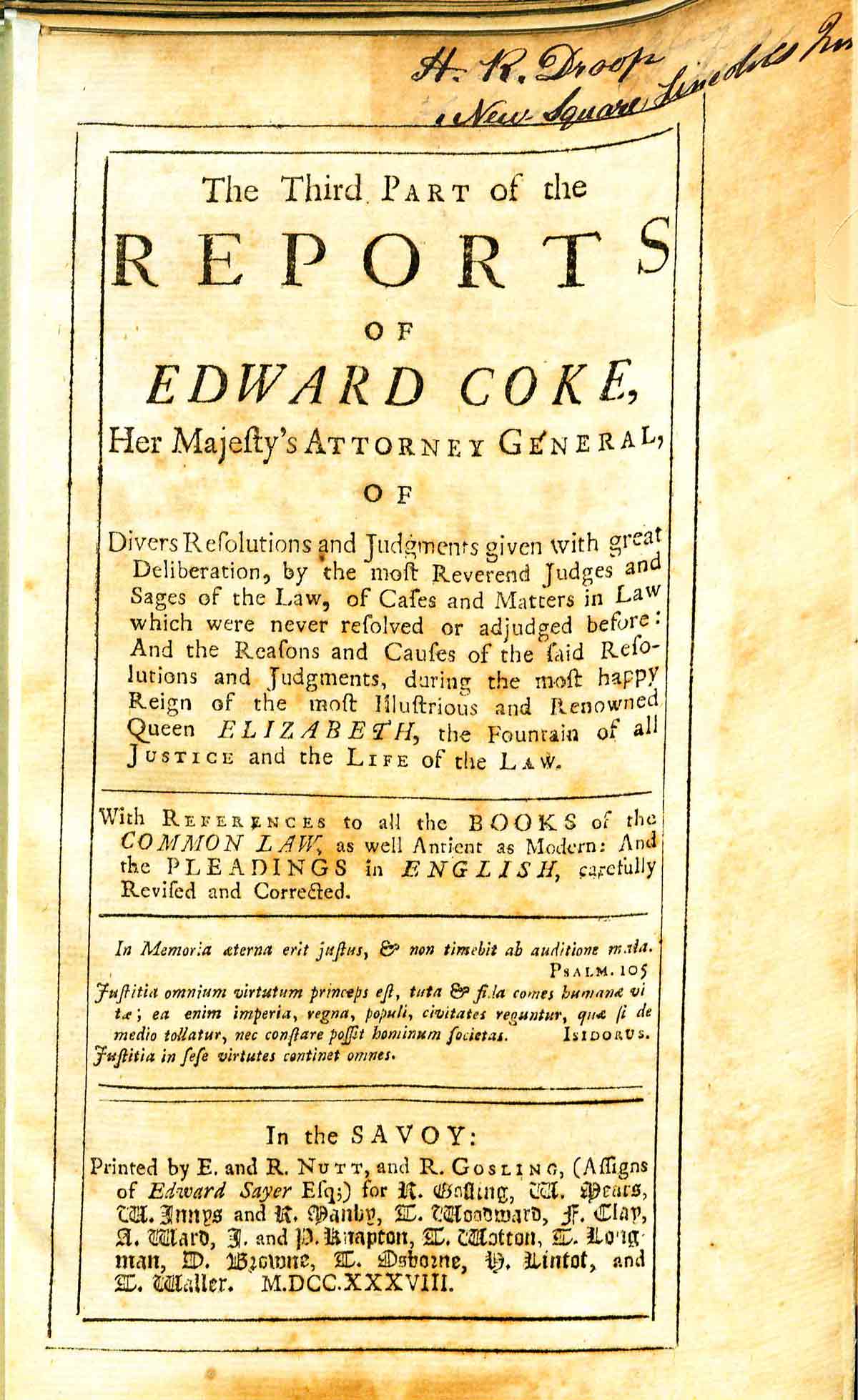

Title page from The Reports of Sir Edward Coke, volume three, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Sir Edward Coke |

| Published | [London] In the Savoy: Printed by E. and R. Nutt, and R. Gosling, for R. Gosling |

| Date | 1738 |

| Edition | Whole newly revised and carefully corrected and translated edition |

| Language | English |

| Volumes | 13 parts in 7 volume set |

| Desc. | 8vo (23 cm.) |

Born on February 1, 1552 at Mileham, Norfolk, Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) was arguably the most prominent lawyer, legal writer, and politician during the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, and a defender of the common law over the use of the Stuarts' royal prerogative.[1]

Coke began his studies in 1567 at Trinity College, Cambridge during the years of the Vestiarian controversy—puritan protests against the Church of England. In 1572 he moved on to study at the Inner Temple, where he was admitted to the bar on April 20, 1578. Coke quickly rose to prominence through his successful execution of several noteworthy cases, such as Shelley’s case. Coke's analytical efforts helped to refine the legal doctrines of English law, and his reputation won him a seat in Parliament. He would later become the Speaker of the House of Commons and eventually attorney general.[2] In 1606, after being created serjeant-at-law, Coke was appointed chief justice of the Court of Common Pleas. He was transferred, against his will, to chief justice of the Court of King's Bench in 1613; he also became a member of the privy council.[3]

After several political and judicial skirmishes with James I and Francis Bacon, Coke was suspended from the privy council and removed from the bench in 1616.[4] Although he never returned to the bench, Coke did return to Parliament and was elected to that body four times from 1620 to 1629. During this time he took a lead in creating and composing the Petition of Right. "This document cited the Magna Carta and reminded Charles I that the law gave Englishmen their rights, not the king ... Coke’s petition focused on ... due process, protection from unjust seizure of property or imprisonment, the right to trial by jury of fellow Englishmen, and protection from unjust punishments or excessive fines."[5] After this triumph, Coke spent his remaining years at his home, Stoke Poges, working on The Institutes of the Laws of England, another endeavor for which he is rightly famous.[6]

"Coke's first well-known work was a manuscript report of Shelley's case, circulated soon after the decision in 1581. In 1600, afraid that unauthorized versions of his case reports might be printed—and probably following the example of Edmund Plowden, with whom he had worked and whom he revered—Coke issued the First Part of his Reports. He put out eleven volumes by 1615. Making available more than 467 cases, carrying the imprimatur and the authority of the lord chief justice, these case reports provided a critical mass of material for the rapidly developing modern common law. Reversing medieval jurisprudence, which had often relied on general learning and reason, Coke preferred to amass precedents. ‘The reporting of particular cases or examples’, he asserted, was ‘the most perspicuous course of teaching the right rule and reason of the law’ (E. Coke, Reports, 1600–1659, 4, preface). Coke began by printing great cases. With the Fourth Part and Fifth Part (1604–5) he shifted to shorter cases, grouped by topics. The Fifth Part featured Cawdrey's case, with Coke's treatise on the crown's ecclesiastical supremacy. Beginning with the Sixth Part (1607), Coke emphasized recent decisions. For his massive Book of Entries (1614) he collected pleadings for his fellow lawyers' better guidance."[7]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Wythe definitely owned this title—copies of volumes six and seven of the 1738 edition at the College of William & Mary include his bookplate and an inscription on the inside front board, "Given by Thos. Jefferson to D. Carr, 1806." Surprisingly, Coke's Reports is not listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library. Perhaps this was an oversight on Jefferson's part, or the title appeared on a lost or damaged page. Three of the Wythe Collection sources (Dean's Memo,[8], Brown's Bibliography[9] and George Wythe's Library[10] on LibraryThing) list the 1738 edition of this title.

Description of Wolf Law Library's copy

The George Wythe Collection includes a complete set of Coke's Reports purchased in 2010, and volume six of George Wythe's personal copy. The latter is on permanent loan to the Wolf Law Library from the Earl Gregg Swem Library at the College of William and Mary.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

George Wythe's Copy, Volume 6

Rebound with original boards, featuring six raised bands. Includes the bookplates of George Wythe and Tazewell Taylor of Norfolk, VA, numbered "166". It is also signed "Tazewell Taylor 1842" and is inscribed "Given by Thos Jefferson to D Carr 1806" beneath the Wythe bookplate.

Complete Set

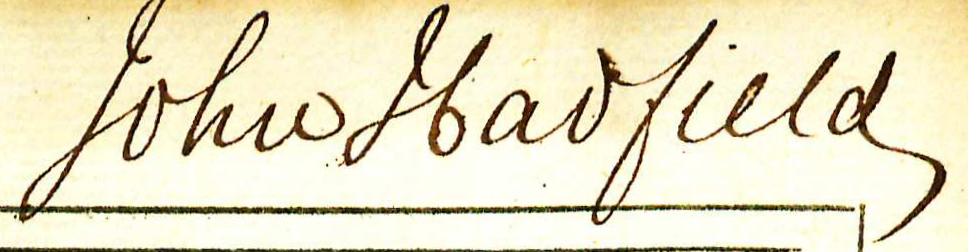

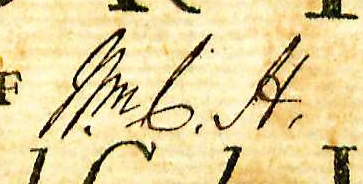

Recent period-style quarter calf over cloth, raised bands and lettering pieces to spines. Includes the inscription "H. R. Droop, New Square, Lincoln's Inn" on the title pages of the first and third parts. Initialed "Wm. C. H." on the title pages to the seventh and ninth parts. Signed "John Hadfield" on the the title pages to the eleventh part and the general index.

References

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. "Sir Edward Coke," accessed October 3, 2013.

- ↑ Allen D. Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward (1552–1634)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed September 18, 2013.

- ↑ Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s.v. "Sir Edward Coke."

- ↑ Bill of Rights Institute website, s.v. "Petition of Right (1628)," accessed October 3, 2013.

- ↑ Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."

- ↑ Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward (1552–1634)."

- ↑ Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean, Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 10 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on June 28, 2013