Difference between revisions of "Platonis Philosophi Quae Extant Graece"

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

Plato’s philosophy centered on the doctrine that there are eternal forms that exist, such as “beauty” or “good,” which human senses cannot fully understand but strive to attain. <ref>Kraut, Richard, "Plato", ‘'The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’’ (Fall 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).</ref> His works do not present a comprehensive system of thought, but instead stimulate discussion and present starting points about how one may question the world.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Plato believed that a philosopher should probe why he perceives the world the way he does, and should apply overarching contemplative ideas (his eternal “forms”) in the moral actions of man.<ref>Alcinous, “The Doctrines of Plato”, translated by George Burges in ‘'The Works of Plato: a new and literal version’’ (London: 1865), VI, pp. 241-43.</ref><br /> | Plato’s philosophy centered on the doctrine that there are eternal forms that exist, such as “beauty” or “good,” which human senses cannot fully understand but strive to attain. <ref>Kraut, Richard, "Plato", ‘'The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’’ (Fall 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).</ref> His works do not present a comprehensive system of thought, but instead stimulate discussion and present starting points about how one may question the world.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Plato believed that a philosopher should probe why he perceives the world the way he does, and should apply overarching contemplative ideas (his eternal “forms”) in the moral actions of man.<ref>Alcinous, “The Doctrines of Plato”, translated by George Burges in ‘'The Works of Plato: a new and literal version’’ (London: 1865), VI, pp. 241-43.</ref><br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | Plato developed this moral theory throughout his works. For example, in the ‘'Republic’’ he explored how to attain happiness by living virtuously.<ref> Mary Margaret Mackenzie, “Plato’s Moral Theory”, ‘'Journal of Medical Ethics’’, 11, no. 2 (BMJ, 1985) pp. 88, 90.</ref> He continuously criticizes social values and political institutions in works including | + | Plato developed this moral theory throughout his works. For example, in the ‘'Republic’’ he explored how to attain happiness by living virtuously.<ref> Mary Margaret Mackenzie, “Plato’s Moral Theory”, ‘'Journal of Medical Ethics’’, 11, no. 2 (BMJ, 1985) pp. 88, 90.</ref> He continuously criticizes social values and political institutions in works including ''Protagoras'', ''Gorgias'', ''Euthydemus'', proving his work is grounded in the practical sphere of human life as well as concerned with the soul.<ref>Kraut, “Plato”.</ref> |

Revision as of 14:58, 8 April 2014

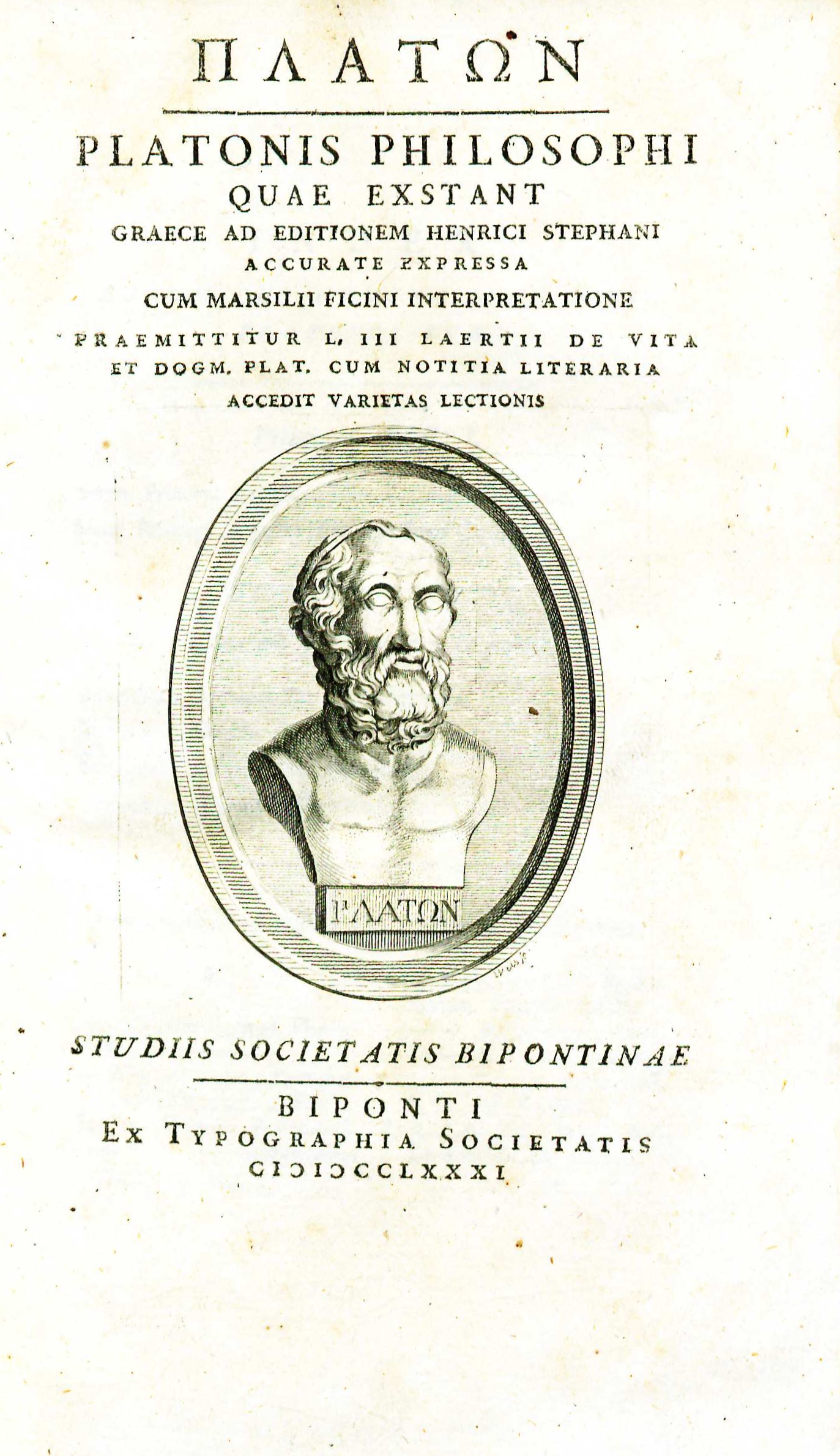

Platonis Philosophi Quae Extant Graece ad Editionem Henrici Stephani Accurate Expressa cum Marsilii Ficini Interpretatione; Praemittitur 1. III Laertii De Vita Et Dogm. Plat. cum Notitia Literaria. Accedit Varietas Lectionis. Studiis Societatis Bipontinae

by Plato

| Platonis Philosophi | |

|

Title page from Platonis Philosophi, volume one, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Plato |

| Editor | Friedrich Christian Exter and Johann Valentin Embser |

| Translator | Rodolphus Agricola (the "Axiochus") and Sebastiano Corradi (dialogues, volume eleven) |

| Published | Biponti (Zweibrücken): Ex typographia Societatis |

| Date | 1781-1787 |

| Language | Ancient Greek |

| Volumes | 11 volume set |

| Desc. | 8vo (22 cm.) |

Plato (429-347 B.C.E.) was a Greek philosopher who studied under Socrates, and is one of the most influential thinkers in the history of philosophy. Little is known of Plato’s early years, but he was interested in politics in his youth, and studied rhetoric under Dionysius. [1] He became a disciple of Socrates, and most of Plato’s works are in the form of a dialogue, many of which feature Socrates questioning various philosophical doctrines.[2] Plato introduced the Western conception of philosophy as a method of thought that probes the boundaries of human senses and understanding of the world.[3]

Plato’s philosophy centered on the doctrine that there are eternal forms that exist, such as “beauty” or “good,” which human senses cannot fully understand but strive to attain. [4] His works do not present a comprehensive system of thought, but instead stimulate discussion and present starting points about how one may question the world.[5] Plato believed that a philosopher should probe why he perceives the world the way he does, and should apply overarching contemplative ideas (his eternal “forms”) in the moral actions of man.[6]

Plato developed this moral theory throughout his works. For example, in the ‘'Republic’’ he explored how to attain happiness by living virtuously.[7] He continuously criticizes social values and political institutions in works including Protagoras, Gorgias, Euthydemus, proving his work is grounded in the practical sphere of human life as well as concerned with the soul.[8]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Plato. Gr. Lat. 12.v 8vo." and given by Thomas Jefferson to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The Brown Bibliography[9] lists the 1781-1787 edition of Platonis Philosophi based on the existence of that title and edition in Jefferson's library.[10] George Wythe's Library[11] on LibraryThing concurs that Platonis Philosophi was the "probable" title in Wythe's Library but no specific edition is listed. One possible problem with the identification of the 1781-1787 edition Platonis Philosophi as the title in Jefferson's inventory is the fact that Jefferson lists "12.v." and this edition only has 11 volumes. However, many copies of this edition, including Jefferson's at the Library of Congress, appear to have been accompanied by Dialogorum Platonis Argumenta Exposita et Illustrata, a Diet (Tiedemann: Biponti, 1786) bound as volume 12. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the 1781-1787 edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

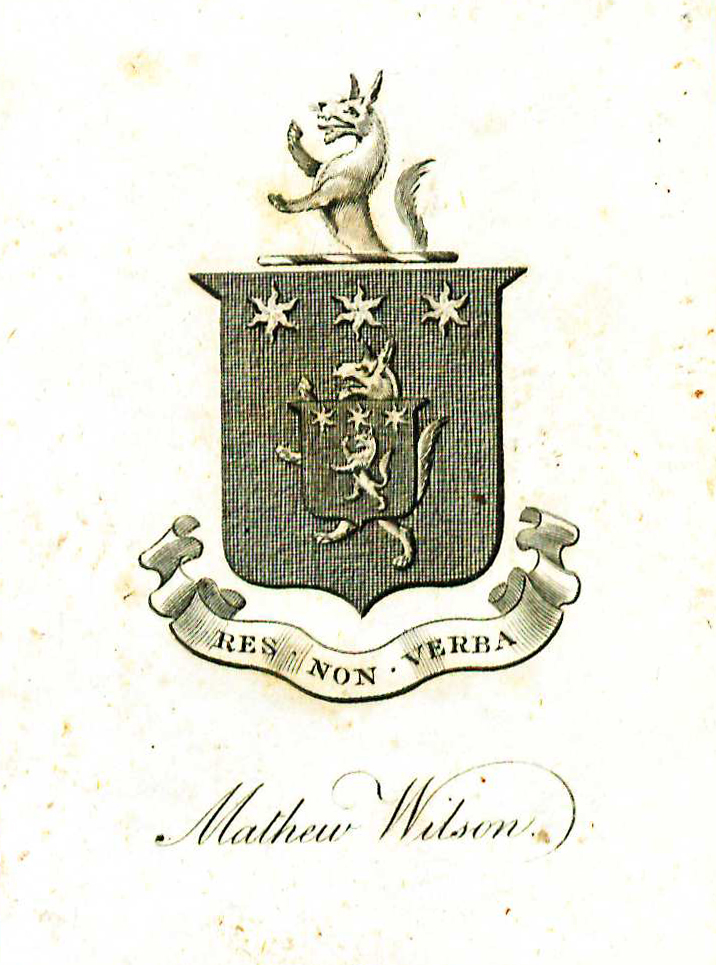

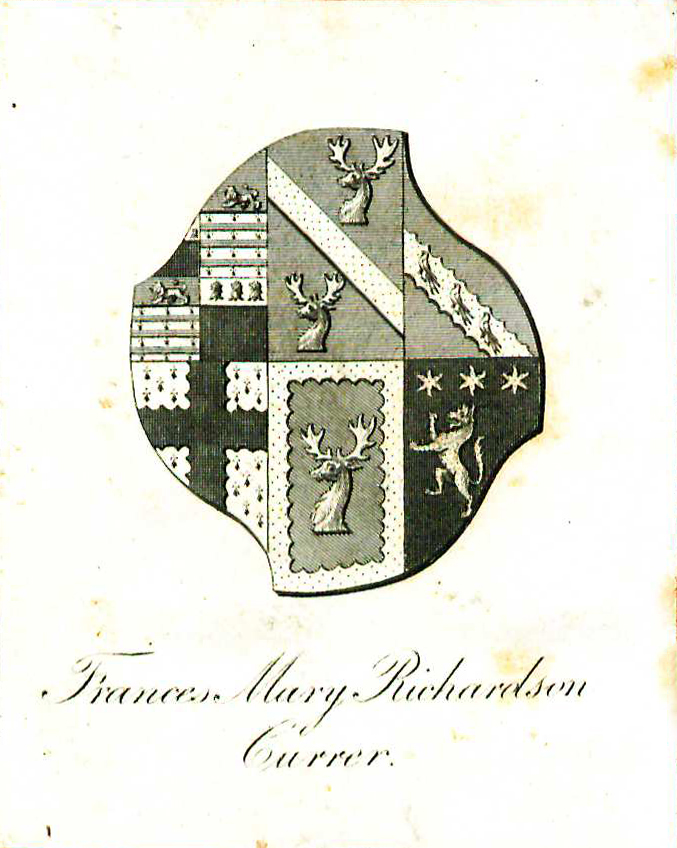

Bound in mottled calf with gilt lining on boards and gilt decoration to spines. Title labels inset on black morocco and copper engraved title vignettes. Each volume includes the armorial bookplate of Mathew Wilson with the Latin motto "Res non verba" (Actions speak louder than words) on the front pastedown and the armorial bookplate of Frances Mary Richardson Currer on the front free endpaper. Purchased from K Books Ltd.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- Jump up ↑ George Boas, “Fact and Legend in the Biography of Plato”, ‘'The Philosophical Review’’, 57, no. 5 (Duke University Press, 1948), pp. 443-44.

- Jump up ↑ Richard Kraut (ed.) ’’The Cambridge Companion to Plato’’, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), page 3.

- Jump up ↑ Kraut, page 1.

- Jump up ↑ Kraut, Richard, "Plato", ‘'The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’’ (Fall 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Jump up ↑ Ibid.

- Jump up ↑ Alcinous, “The Doctrines of Plato”, translated by George Burges in ‘'The Works of Plato: a new and literal version’’ (London: 1865), VI, pp. 241-43.

- Jump up ↑ Mary Margaret Mackenzie, “Plato’s Moral Theory”, ‘'Journal of Medical Ethics’’, 11, no. 2 (BMJ, 1985) pp. 88, 90.

- Jump up ↑ Kraut, “Plato”.

- Jump up ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- Jump up ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 2:33-34 [no.1311].

- Jump up ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on April 21, 2013, http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe